“Gary was so talented it actually haunted him. He wasn’t really in control of what was coming through him. That sort of thing always comes at a price”: How guitar icon Gary Moore snatched defeat from the jaws of victory with his early 80s solo albums

The late Gary Moore made some classic solo albums – but he never got the success he deserved

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

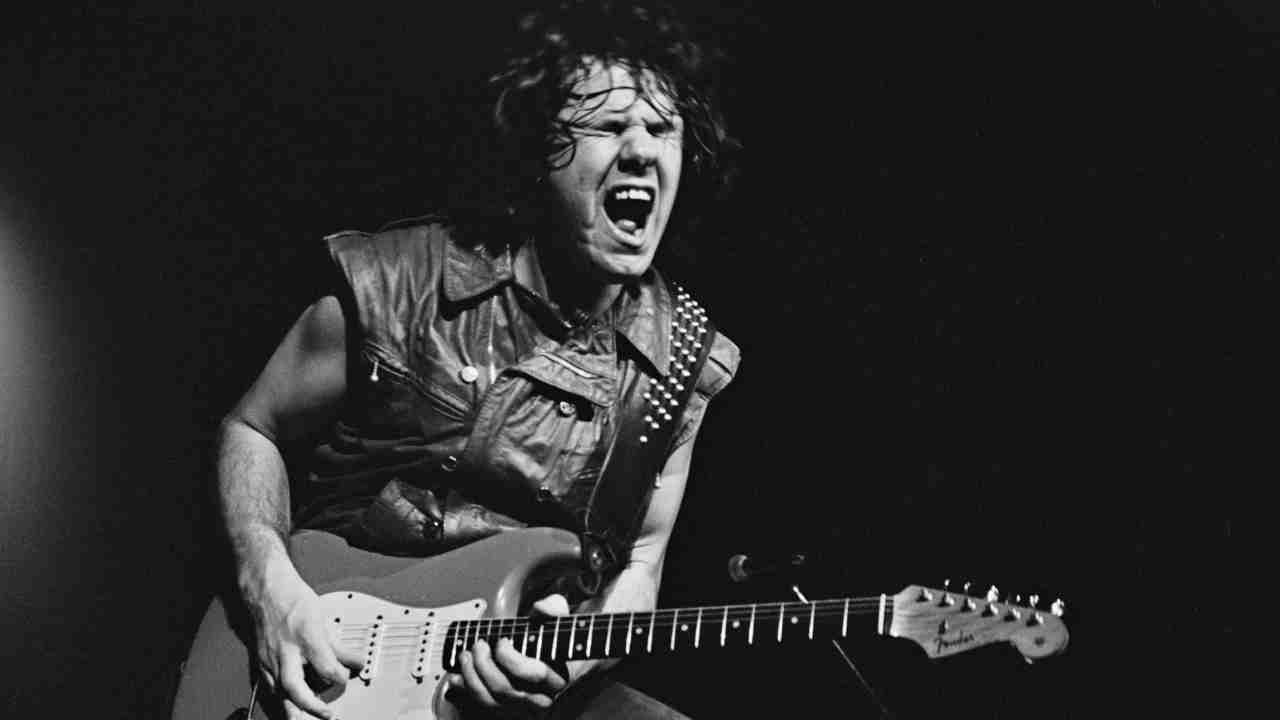

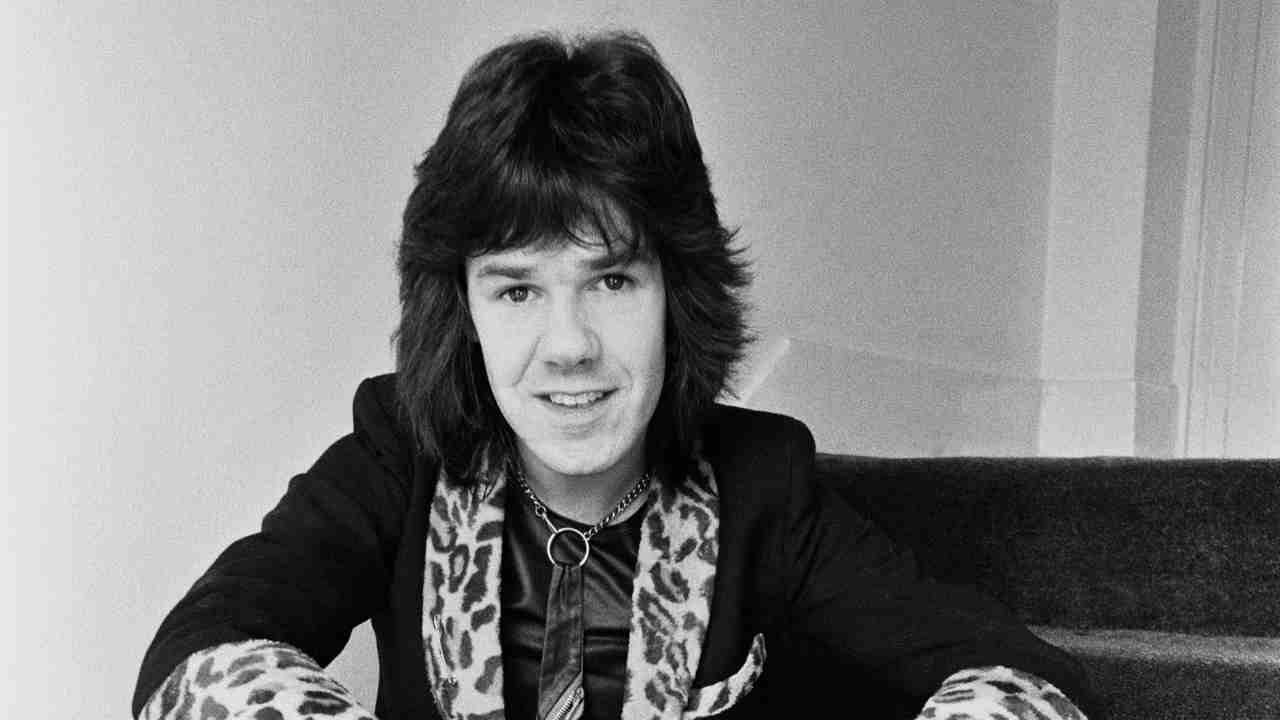

In the summer of 1984, Gary Moore was 32 and living off his reputation as one of the greatest guitarists in Britain. But so what? He’d been hearing about how great he was on guitar since he was 10 years old and playing in Irish showbands. That wasn’t what kept him up at night scowling.

With his disconcertingly scarred face (the result of a pub-fight glassing he was too wasted to remember the next morning) and overeager-Spaniel hair (the result, common at the time, of long-haired 70s rockers updating their haircuts to accommodate the rock-is-dead 80s), Moore appeared a haunted figure, both on stage, where his playing was intensely aggressive even at its most tender moments, and, especially, off stage, where even old friends sometimes came away a little frightened.

“Gary enjoyed success,” guitarist Eric Bell, his boyhood friend and predecessor in Thin Lizzy, told me. “But I don’t know if he was ever really happy. He was a perfectionist, but it was often to his own detriment.”

Moore walked out on his first professional band, Skid Row, on the eve of a US tour, citing frustration with their “limitations”. He was 19 and “very mixed up”. Or as Lizzy’s leader Phil Lynott said: “Gary’s the most contrary c**t I know.”

Belfast-born Moore was the son of a protestant concert promoter. His career began in Dublin working with predominantly Catholic musicians. Naturally left-handed, he had taught himself to play right-handed. “He was always looking gift horses in the mouth,” said Lynott.

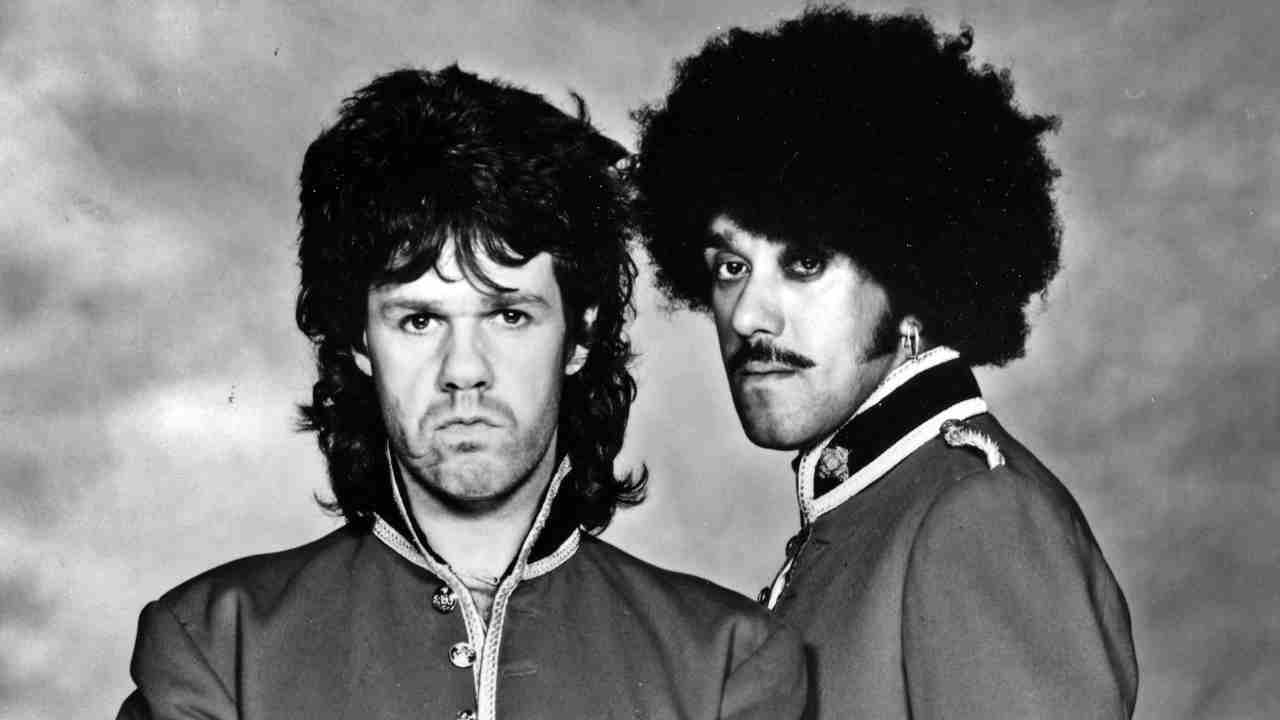

Moore shared a bedsit in Dublin with Lynott, who was three years older and a lifetime tougher, having grown up the only black kid in school. Moore saw Lynott as “like a big brother. He would cook breakfast and take me to the best market stalls to buy cheap stage clothes”.

Lynott had formed Thin Lizzy, featuring guitarist Bell, in ’69. They released their self-titled debut album in ’71 and relocated to London.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Moore formed his own group, the Gary Moore Band, whose debut album, Grinding Stone, came out in ’73. Unlike Lizzy’s heightened blend of Irish roots music, Gaelic poetry and the new electric rock, Grinding Stone was a heady brew of Jeff Beck Group blues, Mahavishnu Orchestra fusion and the Allman Brothers. It was neither a commercial nor critical hit.

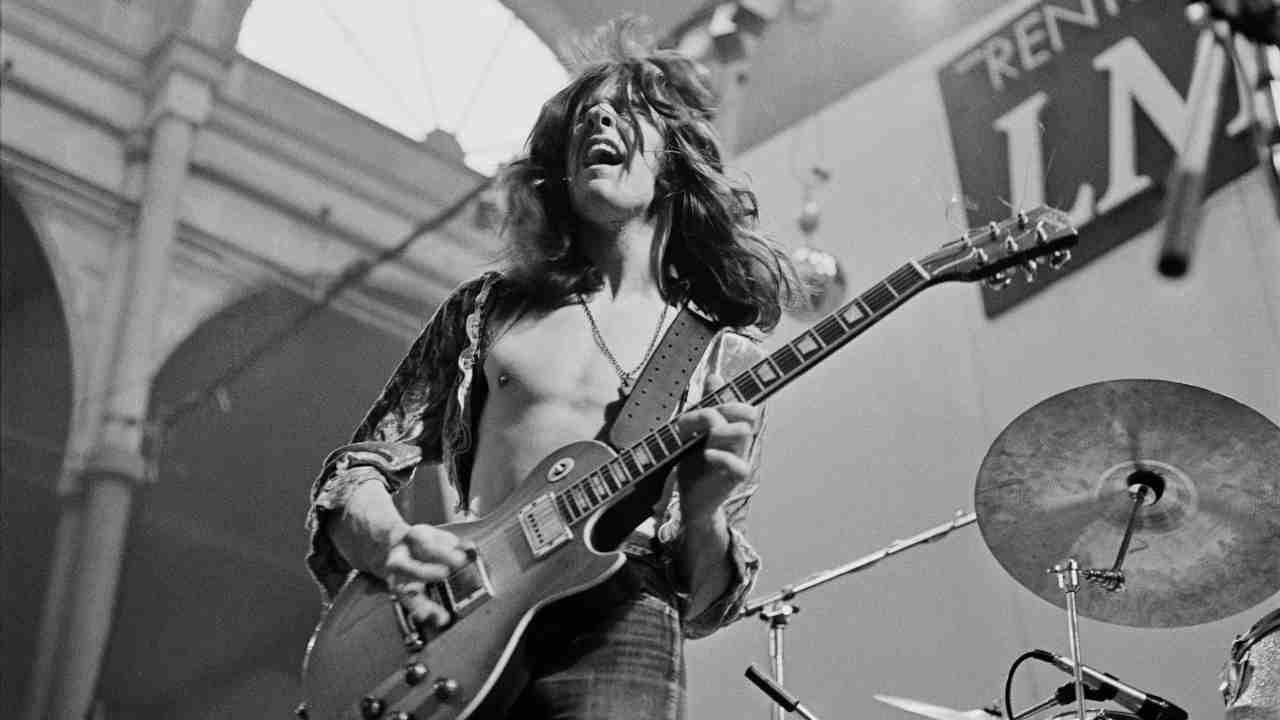

That same year, Lizzy broke through with their wised-up version of Whiskey In The Jar: No.1 in Ireland, No.6 in the UK. But their next album was their third flop in a row. When a disillusioned Bell walked out after a bad acid trip on stage, Moore seemed the obvious replacement. He jumped at the chance, disbanding the Gary Moore Band on the spot. True to form, however, Moore ditched Lynott and Lizzy after one flop single, Little Darling, which had Moore’s Beck-inspired fireworks on full display.

“Gary always had his own thing going on,” says Lizzy drummer Brian Downey. “He didn’t see himself playing second fiddle to anyone, not even Phil.”

Maybe Moore had simply grown impatient with Lizzy’s ‘limitations’, because his next musical move was to join jazz-rock drummer Jon Hiseman in Colosseum II, a prog-oriented, mainly instrumental band that included keyboard player Don Airey and bassist Neil Murray, future go-to session guys for every major British band of the 80s, including various Gary Moore albums. Between 1976 and ’78, Moore co-wrote, played lead guitar and occasionally sang on four Colosseum II albums. The beard-stroking plaudits were many; the record sales pitifully few.

When Brian Robertson, who with Scott Gorham had replaced Moore in Lizzy, cut his hand so badly in a barroom fight that it was thought he might never play guitar again, Moore, at Lynott’s urging, agreed to take Robbo’s spot for a 1977 US tour with Queen. The second Colosseum II album had just been released, but Lizzy were huge at the time and, Gary confessed: “I found the idea of a couple of months of five-star hotels and limos very appealing.”

When, in August 1978, fiery Robbo talked himself out of the band again, Lynott immediately phoned Moore and told him he was back, no arguments allowed.

“When Gary left Colosseum II he didn’t even tell me,” says Airey. “Then I was doing a Black Sabbath session and I heard Gary was in the next-door studio. I went in and there he was in a white satin jacket, white trousers, flowery shirt.

“He was embarrassed to see me. So we never mentioned him leaving. I said: ‘Right, I better get back to Ozzy. See you soon, eh?’ Then I didn’t see him again for two years.”

The next nine months turned Gary Moore into the hottest guitarist in the coolest rock band in the country. Black Rose, Moore’s only full Lizzy album, included three hit singles and went to No.2. The sight of them on The Kenny Everett Video Show blasting out Waiting For An Alibi while draped in Hot Gossip dancers helped establish Moore as an upgrade on Robbo. Moore held the same menace, but had more flash; scar-faced white lightning in skintight pants and gangster shades.

This was a new career peak for Moore. He’d recorded a solo album, Back On The Streets, that featured both Lynott and Downey. Lynott and Downey also joined for what became the album’s hit single, Parisienne Walkways. Sandwiched in the UK chart between Waiting For An Alibi (No.9) and Do Anything You Want To (No.14), Parisienne Walkways (No.8) was more than just pop-catchy – it was rock-immortal.

It was also in 1979 that Moore met former Deep Purple singer/bassist Glenn Hughes. Lizzy were in Los Angeles, where Hughes now lived, readying for a US tour. Scott Gorham introduced them at LA’s numero-uno rock star hangout, the Rainbow, and by the end of a very long night they were best buds till the end.

When, five months later, Moore stormed off stage after Lizzy’s set in front of 63,000 at the Day On The Green Festival in San Francisco, it came as a shock to everyone. Except Moore.

“It got to the point where the party after the show was more important than the show itself,” Eric Bell says.

When Lynott was so wasted he began forgetting lyrics, Moore decided he’d enough.

“There was never any half-measures with Gary.” Bell says. “Such a nice guy on our own, laughing and joking. But if he didn’t like something he’d soon tell you to fuck off.”

With Moore hiding out at Hughes’s place, AWOL from Lizzy, the two talked about starting their own band, to be called G-Force – geddit?

The self-titled G-Force album, released in May 1980, was heavily tipped for the top but sank without trace, helped on its way by the fact that Hughes was nowhere to be found on it – not instrumentally, not vocally, not even any co-writer credits. The two Gs had fallen out after a heavily coked-and-boozed Hughes tumbled over a table at his birthday party and Moore had laughed. They didn’t speak again for years.

Moore was used to people he worked with smoking dope and snorting coke; it was the 70s. But despite an over-fondness for downers when he was younger, Moore didn’t do drugs. He was a drinker. So he tolerated Hughes’s coke habit. Hughes recalls: “Gary didn’t tell me not to do it until 1984, when I was properly high around him.”

After G-Force there was talk of hooking up with Ozzy, who’d been sacked from Sabbath. But Moore didn’t want to be somebody else’s guitarist any more. Born under the sign of Aries, the ram. Zodiac element: Fire. Sign ruler: Mars. Gary Moore was a natural-born leader.

“Gary always hogged the stage,” Downey says. “Even in Thin Lizzy. Phil was the leader – except when Gary joined. Now it was like we had two leaders, which wasn’t very clever.”

Moore returned to London, and in 1982 released his second solo album, Corridors Of Power, another expertly dealt stack of cards with Moore back on lead vocals. But his reputation in the UK was still as the disgraced Thin Lizzy guitarist. The album barely scratched the Top 30.

Hughes also staged a comeback in 1982, teaming up with super-god American guitarist Pat Thrall to create one of the great lost masterpieces, the album Hughes/Thrall.

“Gary was a massive Hughes/Thrall fan,” Hughes says. “He’d completely forgotten about the G-Force incident.”

In the summer of ’84, Moore was touring US arenas opening for Rush, before coming ‘home’ in August to appear at the Monsters Of Rock festival at Castle Donington. His latest album, Victims Of The Future, had found a winning formula that fitted the Kerrang! crowd – guitar-heavy rock blended with American-flavoured pop-metal – and had a woulda-coulda-shoulda hit in the power ballad Empty Rooms. It was his first UK Top 20 album, despite Empty Rooms failing to reach the Top 50. A first headline solo show at London’s Hammersmith Odeon followed. Then a headline solo Japanese tour.

With a week to kill in LA on the Rush tour, Moore had arranged to stay at Hughes’s palatial Northridge mansion. The only snag was that his host was now a full-time, pipe-sucking crack addict. Hughes “put the pipe down” for a few days while he showered, shaved and tried to “look like a normal guy – for Gary”.

The illusion held long enough to persuade Moore that another team-up with Hughes could work. So the seeds were sewn for what would become Moore’s pinnacle 80s solo album: Run For Cover.

There would be more albums to come on which Moore incorporated trad-Irish rhythms, pure American blues, burlesque pop-electronica, even drum’n’bass into his sound, but he never made another true-blue rock album like Run For Cover. He’d walked out.

When Hughes flew into London to begin work, Moore’s manager insisted that Glenn lay down some collateral. “In case I fucked up.” They took one of his cars, a black Volvo he kept as a runaround. In return, Hughes was given at a luxury flat to stay in while the two began writing material. Material that Hughes would later receive no credit for, he explained, because Moore “controlled every aspect – from the syncopation of your bass, to what notes you play, to what you sing”.

Once, Hughes screamed at him: “Why don’t you play the fucking bass yourself?” So Moore did.

Moore adored Hughes’s singing voice, and decided all lead vocals would be split between them 50-50. Hughes would eventually sing lead on four of the album’s 10 tracks.

Moore was such a Hughes/Thrall fan, according to Hughes, that the title track, Run For Cover, was “basically a rip-off of I Got Your Number”, the opening track on Hughes/Thrall. In his 2011 memoir, Hughes writes: “I Got Your Number was a huge influence on Gary. You can definitely hear it on Run For Cover.”

It was true, especially the tracks Hughes sings on, like the strutting Reach For The Sky or the swaggering Nothing To Lose or, best of all, the sassy All Messed Up. Even the freshly frosted Empty Rooms shone like new.

But with Hughes jonesing for crack and Moore oblivious to his pain, the tension in the studio quickly escalated. Hughes would wait for Moore to leave for the weekend, then hit the Embassy Club in Mayfair with Lemmy, who “could handle his drugs, I couldn’t”. Hughes was also midnight feasting, and at one point tipped the scales at 220 pounds/15 and a half stones.

He had originally sung lead on the new Empty Rooms. When Moore’s manager insisted Hughes lose weight and get his teeth fixed in order for them to perform it on Top Of The Pops, it led to a full physical examination. When blood-test results revealed the hideous truth of what Hughes had been up to in his spare time, he recalled: “I was on the next fucking plane. There was no conversation about it. I was gone.”

Needless to say the Hughes version of Empty Rooms never saw the light of day. When a still disgruntled Moore ‘revealed’ in an interview that Hughes had a food addiction, calling him Mr Creosote, “it really hurt me”, Hughes confessed. Moore was “not a man to fuck with. He didn’t have the scars on his face for nothing.”

Another estranged friend that Run For Cover would reconnect Gary with was Phil Lynott. Moore had guested one night on Lizzy’s official farewell tour the year before. Lynott spent all of ’84 trying to get a new band, Grand Slam, off the ground, but there were no takers. Meanwhile, it was common knowledge that Lynott was filling the void with heroin.

When Moore embarked on a four-night run in Ireland that Christmas – two in Belfast, two in Dublin – he invited his ‘big brother’ to come on for the encores each night and do Parisienne Walkways. Back in London, in January ’85, Moore invited Lynott to join him in the studio to record a track he wanted them to do together. It was called Out In The Fields, a song about equality based on the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Phil, though, had endured a “heavy Christmas” and was in bad shape. Moore once described him as “one of the most charismatic and charming fellers you could ever hope to meet, a real Irish gentleman”, quickly adding: “Unless you got on the wrong side of him, of course, and then he could be a real fucker.”

The Lynott in the studio that day, however, was different. “Phil in the early days was always the first guy in the studio and the last guy out. Such a workaholic. But when the drugs kicked in I saw a big change. He’d start each day with a spliff in one hand and a glass of whisky in the other.”

Losing Thin Lizzy had affected Lynott deeply. Now his wife, Caroline, had left him too. “Without his wife and his kids, Phil was living on his own in this big house with a bunch of leeches,” Moore seethed. “Dealers and smack-heads.”

Moore begged. “Please, Phil… Saying I loved him and how I really wanted him to stop. He’d be like: ‘Oh yeah, I’m gonna do it but I’m not gonna do it overnight.’ Then the next day he’d be back to his old tricks.”

When the Out In The Fields single went Top 5 in June, it not only transformed Moore’s career, it also opened doors to a new solo deal for Lynott. “John Sykes said: ‘Oh, it’s really nice of you to work with Phil,’” Moore recalled. “But I didn’t see it as doing Phil a favour. It was his packaging of the whole thing which helped to make it such a big hit. The military uniforms we wore during the promotion were Phil’s idea. He had a gift for marketing, a great sense of how to sell to an audience.”

When Run For Cover was released in September, Moore toured the UK, and Lynott guested on Parisienne Walkways and Out In The Fields at Manchester Apollo and both nights at Hammersmith Odeon. “No pressure, no hard work, no hassle, but plenty of limelight and a great excuse to get wasted every night. I knew what he was up to,” Moore said.

The new Empty Rooms was the follow-up single to Out In The Fields. It reached No.23, didn’t become the hit that Moore thought it should have been.

“Gary was so talented I think it actually haunted him,” says Don Airey. “Once he got the guitar on, he seemed to connect. But he wasn’t really in control of what was coming through him. He couldn’t stop it. He was a genius, really. That sort of thing always comes at a price.”

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.