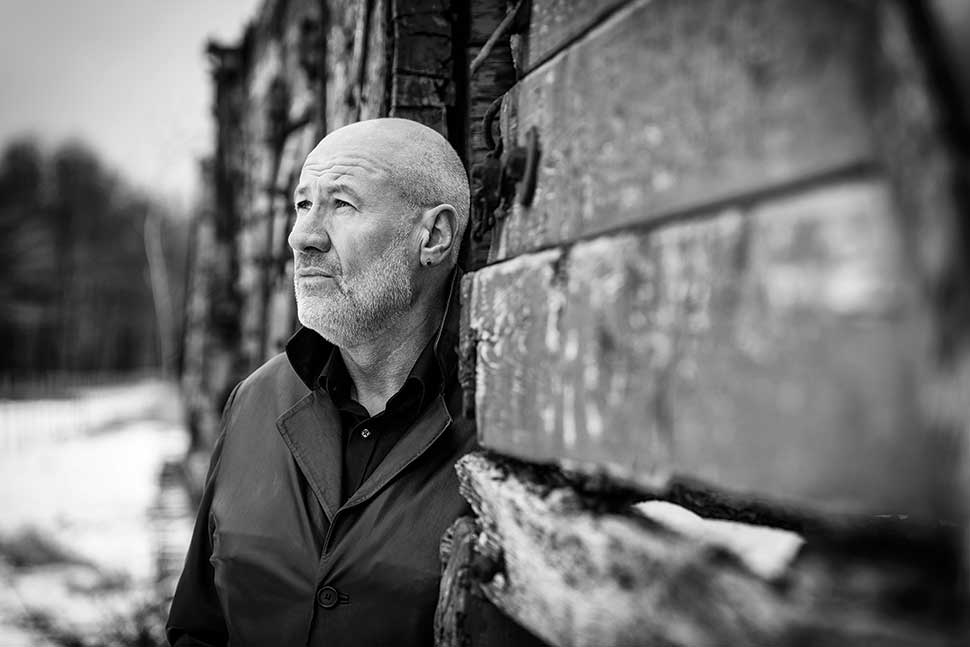

Fish bids farewell: the pain of the world and the album he was born to make

After spending the last four decades immersed in music, Fish is calling time. But with his farewell album, the prog legend is signing off with the best record of his solo career

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

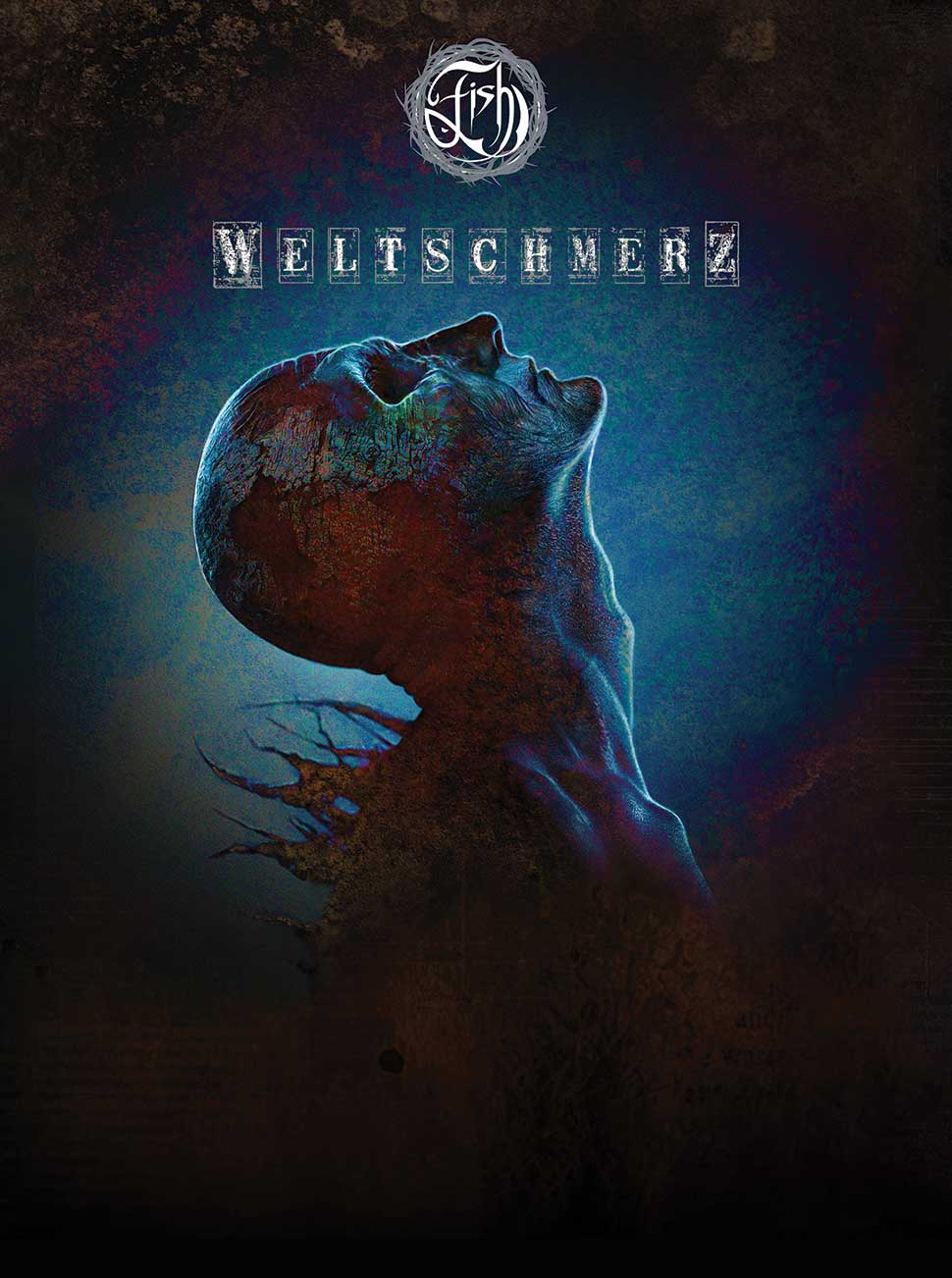

Illness, old age, death, war. They don’t sound like the most promising ingredients for making what turned out to be one of the most uplifting albums of the year. But that’s what Fish has done on his new – and, he says, final ever – album, Weltschmerz (literal translation from German: ‘world pain’, generally: world-weary).

There’s a lot to unpack here but let’s start with the concept behind Weltschmerz. Ostensibly a double album – two CDs comprising 10 tracks, totalling around 84 minutes of music – the idea took hold in the aftermath of the death of Fish’s father, Robert, in 2016.

“You can prepare for somebody close to you dying. You know they’re going to go, and you mentally build all the walls to deal with this emotion that you know is going to come at you. Then it happened and it struck me in a completely different way to what I expected. I just focused, blocked everything off. Then when the funeral was over I locked myself in the garden for, like, seven months, just doing nothing. I couldn’t write. Couldn’t do anything. I didn’t get the first thing written on paper until the end of 2017. That was Little Man What Now?.”

Talking via Skype from his countryside home outside Edinburgh where he’s lived for 30 years, Fish goes on to explain how his father’s death was followed soon after by his own multiplying health problems: operations in 2017 on his spine and, separately, his shoulder, have been followed more recently with operations on his heart and his hands, and a near-death experience with sepsis (caused by the body’s response to an infection).

“That was all within the tail of the comet of my father’s death. I was in and out of hospital all the time. I was just aware that I was getting old. I turned sixty in April 2018 and I thought: ‘It’s time to go.’”

Other factors that contributed to Fish’s growing sense of mortality included the decision to put the album release back for a year while Mark Wilkinson recovered from cancer.

“Mark has designed every album I’ve ever done from [Marillion’s] Script For A Jester’s Tear right through my entire solo career. I wasn’t making a final album without him.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Throw in the continuing fallout from Brexit, the shock and awe of Trump, and now the whole world forced to the precipice of destruction by a global pandemic…

“I think I’ve always been in tune looking at the world around me. If you listen to the lyrics of Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors, it’s just as relevant to now. It’s strange, but I’ve always had that. Maybe when Kayleigh came out in that summer of eighty five. It was on the radio, and it just tuned in like some virus into people’s heads. That was the ‘now’ song then.

"That’s what I wanted to do with Weltschmerz. I wanted to take these people that were in dark and lonely places, bring them together and assure them there’s a beauty in there, that there can come a strange beauty out of it all."

When Fish first spoke of his intention to actually retire from music, I assumed he would eventually change his mind – especially if the ‘final’ album turned out to be the jewel that the startling early demos he’d played me then suggested. Instead, the fact that Weltschmerz is his greatest record since Marillion’s towering Clutching At Straws, his last album with the band before abandoning them at the peak of their powers in 1987, has only reinforced his decision to make it his fond adieu.

“The reality is I don’t want to be on a tour bus for the rest of my life. I’m never going to be playing stadiums or arenas again. And I definitely don’t want to be on the chicken-in-a-basket circuit singing fucking Kayleigh. But all these operations and being aware of the mortal coil and everything else that came in, the experiences, it all just fed into the album.”

You can hear that from the ghostly chattering atmosphere of opening track Grace Of God. Inspired by a lengthy recovery period in hospital following the second of two nasty bouts of sepsis – “I was laying there hooked up to intravenous tubes, cannulas sticking out of my wrists” – it sets the scene for what, it quickly becomes clear, is a monumental body of work. Eight minutes of slipping in and out of consciousness, music as fever dream, disembodied voices, words-sharp and precise as a needle in a syringe.

It’s followed by Man With A Stick, instrumentally the closest descendent of rock, but thematically as angrily appalled yet deeply empathetic as anything else here, a remembrance of things past that contains the bloodied sweep of the latter half 20th-century history

I definitely don’t want to be on the chicken-in-a-basket circuit singing fucking Kayleigh"

Fish

It’s the same with every track, the personal as political, music as first memory-muscle quickly cascading out into flows of imagination far beyond normal limits for this kind of thing. And that’s before you come to the cornerstone epics like Rose Of Damascus, almost 16 minutes long yet impossible to turn away from. Ostensibly it’s the tale of a young woman refugee fleeing the Syrian war, but you don’t need a microscope to detect the more subterranean themes also attached.

“When Mark Wilkinson and I first talked about it, he said: ‘You have to do this in third-person. You can’t write it in first, it’s going to be too heavy, too personal.’ So that’s what I did. Then I found out suddenly, all that third-person stuff was just completely infused with me-ness. When I started singing Waverley Steps in 2018 I went: ‘Fucking hell, this is me.’ I didn’t realise. There are some of the songs on the album that are a lot more of me than I intended to put in.”

Indeed, while the words – always Fish’s calling card – are more acutely refined and loaded with poetic imagery than ever before, it’s the astounding music, by Fish and long-time co-writer Steve Vantsis, that makes the deepest cuts run so red.

Prog fans will no doubt delight at the sheer scope of tracks like Rose Of Damascus, Little Man What Now? (10.54) and Waverley Steps (13.48). But they won’t find any Marillion-era widdly keyboards and guitar solos. The sound on the album is daringly promiscuous: horns, strings, accordion, spoken-word passages, special effects all making for a cinematic experience.

“Calum is the man,” he says of his long-time collaborator, keyboard player, producer and mixer Calum Malcolm. “Steve Vantsis has also got a co-producer credit on it because that was the way we built it – me and Steve building the songs from scratch, then Calum taking it further down the line. Calum was so flexible in the way that he dealt with our studio time. Steve and I both have our own ‘personal issue’ things, but the three of us found away to absolutely merge together beautifully."

Fish says he resisted the temptation to bring in some big-name guests, as he did on his last album. “It would have diluted the soul of the album,” he says. “So all the people that are on it we already knew. Calum was over the water in Fife, Steve’s down in Birmingham. Calum would be sending the mixes, and as we’re listening he’s messaging: ‘I’ve got a better one coming.’ He told us he never did more than five mixes of a track. But on this it was the seventh mix every time.

"I was fucking in tears when I first heard Rose Of Damascus. There were moments at the start where I seriously doubted we’d ever get it. Calum just kept saying: ‘Don’t worry.’ And he was right.”

The way Weltschmerz is presented also contributes to the immersive experience it delivers: CDs, DVDs featuring an interview with Fish and Mark Wilkinson, 5.1 surround versions, live tracks, new track videos… most impressive of all, the 100-page booklet-box that contains the whole caboodle. Not just all the lyrics and info, but also Fish’s story of how the album came to be. As refreshingly honest as we have come to expect from the guy who has always worn his heart like two upholstered pistols in his hands, but also beautifully written. All this set off by Mark Wilkinson’s gorgeous and evocative images.

“Mark did a brilliant job,” Fish says. “As a final statement it’s breathtaking. You can see the journey he’s made from the original jester image on the first Marillion records up to this. The visual references to plants and garden life is also something I asked him to consider, because of my own affinity with my own gardens. We grow our own vegetables, fruit and of course hundreds of beautiful plants and flowers.”

The whole becomes an anomaly in the digi-streaming age: a work of musical and visual art that you actually want to spend time on: to listen to, to read, to absorb, to form a meaningful relationship with. Some tracks, such as the fragile piano ballad Garden Of Remembrance, are so beautiful they became almost painful to listen to.

“I didn’t want to go out with an absolutely duff album. I thought there’s enough in me to really go for it and just make something really special. Let’s put everything into one last big effort and do it and call it.

“I was running out of subject matter to write lyrics about. I’ve done heartbreak. I’ve done the futility of war and the soldier’s promise. I’ve done the relationship stuff. I just went: ‘What the fuck am I going to sing about? And where are these melodies going to come from?’

“At the same time, the world moved on, from the Syrian civil war into a full Middle Eastern crisis. We moved into dramatic climate-change issues. We moved into Trump, Brexit. We moved into so many world issues that were overwhelming. I felt fucking helpless, but I could feel it and I wanted to change it, which I think came up in the title track. But Weltschmerz, a pain of the world, it’s become overwhelming now. I could’ve called the fucking thing Zeitgeist, because the feeling of the album is totally in tune with now."

This is the album that I always wanted to hear when I was seventeen. The album I always wanted to make as a musician"

Fish

Then there is the voice. The Marillion heydays when Fish sang like a cross between 70s-era Jon Anderson and Genesis-era Peter Gabriel are long gone. Now, with his mumbles, whispers and almost walking-pace vocals, he sounds more like Leonard Cohen.

He laughs. “I’ve always said I am a writer who can sing; I’m not a singer who can write. And my voice has changed because of what’s happened to me over the years. I’ll listen to Script or Fugazi now and I don’t even identify with the person who sung that. It seems like it’s somebody else.

"I had big vocal operations in 2009. I had to retrain my voice. I had to go back into the gym again with the voice. By doing that it made me examine the mechanics of songwriting. I found my real voice when I wasn’t shouting over electric instruments. But it’s found a really good place, because when Steve and I put the keys together, he knows that I need the ceiling, he knows that I need space to play about in.”

He recalls listening to the finished album for the first time, and experiencing a sort of epiphany. “I didn’t have a drink for five months, and one of the first bottles of wine that my wife and I opened, we sat on the couch and listened to the final mixes. We actually listened to it three times. I thought: ‘This is fucking brilliant. I love listening to this.’ This is the album that I always wanted to hear when I was seventeen. This is the album I always wanted to make as a musician.

"At the same time, it was a relief that I’d finished it. I’d done what I set out to do: to make an album of the calibre of Weltschmerz. And there was an added euphoria because this is the end of my recording career. This is it. There’s no more songs. I am now moving into the beginning of another life."

So what does the future hold for Fish, the now ex-rock star? Does he still write songs?

“I still pick up things. There are still moments where I’m listening to the TV and somebody will say something and I’m like: ‘Oh wow, that’s a good idea for a song.’ Or I’ll hear a phrase and I’ll go: ‘I could use that.’ But they’re fleeting. They’ll fizzle down. They just run by and I’m not noting them down. Because I’ve got other things I’m thinking about now. Screenplays. I always wanted to be an actor, but I’ll never be an actor now. I might get bit parts or whatever, character roles. But I love movies. I think Weltschmerz is very affected by my experience in movies and why I like movies and what I like.”

Fish’s best material has always been cinematic. “The natural step to take is to go screenplay writing. Because every one of those songs on Weltschmerz, you could make a short film about them or a film. I’ve never written a screenplay before, but in 1981, when I joined Marillion, I’d never written a song before. I don’t understand music. I don’t know all the technicalities. I’ve just got a feel for it. It’s the same with movies. I’ve just got a feel for it, especially through words. And I’ve had tons of ideas for screenplays over the last twenty years.

“I was talking to a film director friend of mine. He works up in Scotland, does a lot of independent stuff. I said: ‘I’ve got this idea.’ So we sat and talked about it, and he goes: ‘This is brilliant. This is a Netflix pitch!’ So I’ve been working on that. And it’s a serious fucking pitch. It’s a big historical drama. Although it’s so left-field it embraces so much stuff.

"I’m researching that at the moment. That’s why I’m keeping it very close to my chest. I’ve got shitloads of books that I’ve got to go through, to find out what angle I’m going to take, how it works. Will Smith the writer is a big friend of mine. We’ve been talking about this for years and he’s been pushing me and going, you got to get into this, you got to move into it. And that’s what I want to do.

"I’m scared because I could fall flat on my face. But then again, fuck it. My approach has always been the same as with Weltschmerz. I never at any point thought: ‘Are people going to like this?’ I like it, this is what I want to do, that’s enough. That’s always been my benchmark.”

It’s an assertion born out of a career in which Fish achieved the most success by deliberately railing against whatever the received wisdom was at the time. Most eventfully when Fish fought for Misplaced Childhood, Marillion’s third album, to be promoted as a concept album comprising one continuous piece of music.

It was an idea so discredited in the 80s that even his staunchest supporters, including this one, thought he was out of his mind. Result: the band’s first No.1 album, first massive hit singles, first US success, first taste of the millionaire rock star lifestyle.

“Misplaced was significant for me not because of the commercial success, but because I had the confidence at last to express myself openly. Before, I hid with the songs. They were wordy, they were flowery and I sang them while hiding behind the face make-up. But on Misplaced I went: ‘This is me.’ That had a lot to do with that album. And on Clutching I followed it on, and I opened myself up even more.”

This is it. There’s no more songs. I am now moving into the beginning of another life"

Fish

Do you remember the first time you went on stage without the make-up? “Well, I didn’t go on without it. I phased it out. By 1984 it went from full-face make-up to really just the eyes. Then it just became eye shadow with a couple of bits on it, and then it was gone. But it was as I grew up I became more confident. I remember meeting Paul Stanley in a club in New York and he went: ‘Gene really liked your make-up, man. You’ve got it all copyrighted?’ I went: ‘No.’ I never thought of it like that. It was different every night, depending on the mood.

“I’d never sung my own songs before Marillion. And I was hiding. Like: ‘This is a guy called Fish. This isn’t Derek. This is a guy called Fish behind a mask.’ And if I fucked up I could take the makeup off and walk away and be like: ‘Oh, the other guy did that. Big guy did it and walked away.’”

He still insists he has no regrets about leaving Marillion when he did – just as they were about to sign a million-pound publishing deal, on the verge of becoming big in America. But he’s old enough and man enough now to regret the manner of the divorce. He and Tammy – the girl from Berlin in the Kayleigh video, who he would marry and then separate from just a few years later – “were not in good shape by any stretch of the imagination. And there were drugs and alcohol around everybody, you know?”

The band was being mismanaged, in his view, being kept out on the road too long because of the money. He smiles ruefully and lights another smoke. “I was very impetuous. The me today, if I was in a situation like that, would probably have tried to talk it through. But me back then was like: ‘Fuck it. I’m out!’

"Ultimately I really, honestly believe that I did the right thing. I’ve had a great life, and I’m still here and I’m happily married. I’m the singer with a studio. Christ, I’m the last person in Marillion that ever should have had a studio, right? I should have had a pub."

It would make a great movie.

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.