Far's Water & Solutions at 25: "We were a mess... and on that record it was a beautiful mess”

A cult hit upon its release on March 10, 1998, Far's Water & Solutions stands as one of the most revered and essential post-hardcore albums of all time

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Jonah Matranga used to wonder what it might be like to walk out into the street and get hit by a car. At the time, his band were busy writing their signature recorded statement, Water & Solutions, when he was not much older than those songs are today. Depression’s hold had a tight grip but offered a sanctuary of sorts. It represented a numb armoured bubble where he could hide.

“I was struggling inside, and everyone [else] was doing great,” the former Far vocalist wrote in his 2017 autobiography, Alone Rewinding: 23 Years Of Fatherhood & Music. “In therapy, I began to notice that as shitty as depression felt, it was a safe place for me. It gave me an excuse not to go out, or try.

“I used to think of depression as something that was pursuing me,” he continues. “I had a recurring vision of running along some endless tundra, panting and panicked, a leopard at my heels. Sometimes it would catch me, but it would never kill me. It would hold me down, and I would feel its breath… I started to think of it as an old friend that I didn’t want to hang out with anymore. It was my choice to say goodbye to it. I wrote it breakup songs. Wear It So Well was one of them. I Like It was another. They helped.”

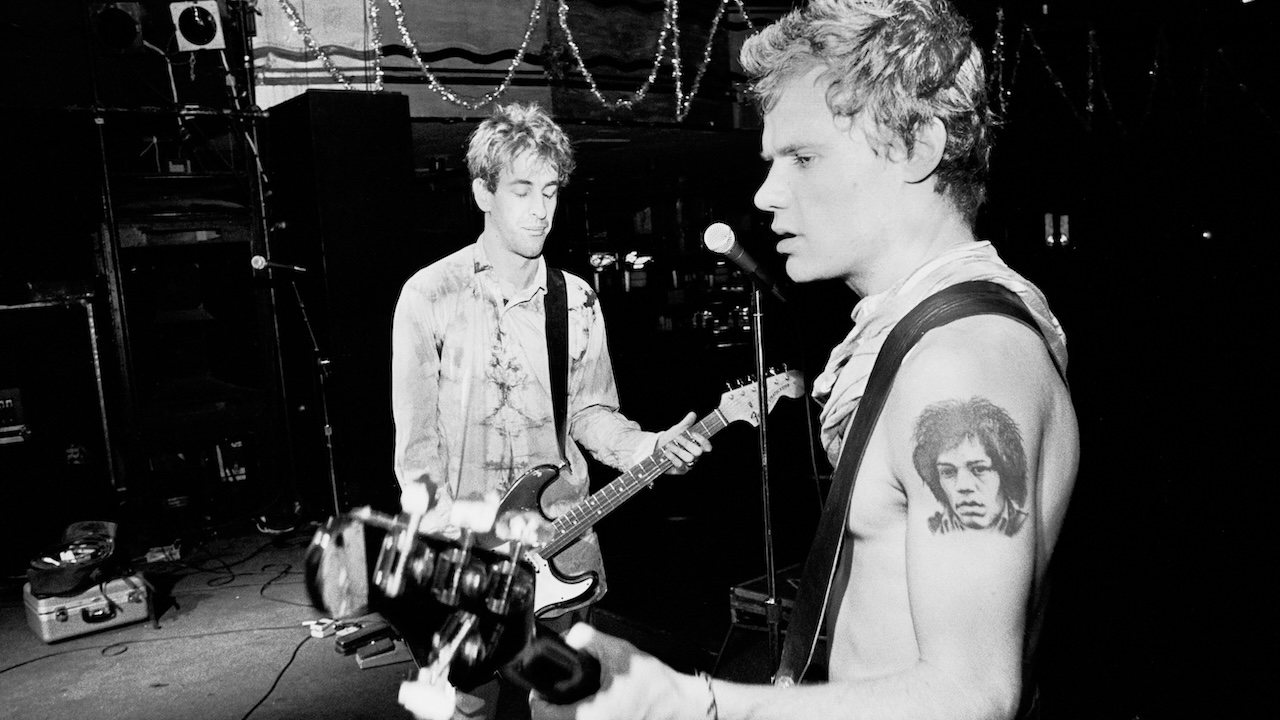

This was the powder keg situation against which the Sacramento quartet – completed by guitarist Shaun Lopez, drummer Chris Robyn, and bassist John Gutenberger – were attempting to repay the investment and the faith shown in them by their label, Immortal Records. When their previous, 1996 release Tin Cans With Strings To You sold 10,000 copies, they self-deprecatingly joked about “going brass”. Even in the weirdo Wild West of mid- ‘90s alt.rock, Far stood apart, anomalous. The self-styled “anti-macho-rock misfits” had gained some attention, thanks in part to popular TV show Buffy The Vampire Slayer soundtracking a dramatic scene with Job’s Eyes, a sad, angry song written in tribute to one of the frontman’s childhood friends who had taken his own life. Still, no one was expecting a sudden hit and tensions were running high.

“It had settled in that we weren’t a simple equation,” the vocalist explains. “As confusing as we were to the people pouring money into us, I think it was getting to us just as much. We were growing up as a band and as individuals, finding our voices. What wasn’t clear was what those voices would sound like on the same album, and if anyone would like it enough to pay for it. After all our fighting, by the time me or Shaun had gotten what one of us wanted, or we’d all just settled for a paralysed place, the peace was so fragile.”

But within that tension, Far conjured magic. Fittingly enough, they did so at The Magic Shop in New York City, over six weeks in the spring of 1997. While recording, the label booked them into a small SoHo apartment overlooking the iconic Moondance diner, where they tried not to kill each other. Moby dropped into the studio to say hi to producer Dave Sardy one day, imparting wisdom about writing what’s true. At a karaoke night on the lower east side came the surprise joy of witnessing R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe bringing down the house with Rhinestone Cowboy. But Matranga was missing his young daughter back home on the west coast and his marriage was rapidly falling apart.

The tracks reflected all this tumult, touching on themes of family, spirituality, the way of the world, and how people find their place in it (or don’t). Nestle, for example – the oldest of the lot – started out as a quietly seething song inspired by his late father and the complexities of their relationship, later evolving to reflect his own patriarchal responsibilities. Its concluding image of the ‘holy ghost’ is just one of the album’s many references to Christian iconography. Those are most pronounced against the vibrant, slaloming riffs of its most instant track, Mother Mary. “Dominant culture bleeds into brains,” the singer says of its religious tropes. “It’s an ugly sort of osmosis.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Lots of the record came about by happy accident, however. The title is a straight lift from a scientific journal randomly found amongst some garbage on a stroll one day. Bury White, a song of “complaining and complacency”, got its title after Sardy joked that the lyric ‘soothe me lover’ sounded like a Barry White line. Perhaps as pertinent as what the songs are surface-about or suggestive of, is how they’re captured, delivered, and what that sounds like.

The producer – not yet the go-to guy for all things heavy that he would later become – was chosen to help “chisel and shape” the band in a way they simply couldn’t have managed on their own or with somebody else. Writing in the 2004 reissue liner notes, Gutenberger credits him as their “fifth Beatle”, noting his ability to cut through the noise of their disagreements, whittling things down to their essential sinews. Thanks to his input, Really Here’s sprawling five-minutes became an elating two. “Almost all the songs got shorter,” Matranga remembers, “and all of them got better.”

For an album built on fragile foundations, it came out sounding vacuum-packed. A band often misunderstood by the industry and audiences alike, had finally happened upon something that made sense and represented them best. It was but a fleeting, bittersweet moment, alas. With mixed results, the quartet subsequently hopped onto bills with hometown friends Deftones, Incubus, Life Of Agony, and even Monster Magnet. No one really knew where they fit in. The “stressful silence” of the US headline tour that would ultimately end things spoke volumes. It was only in the years that followed that their influence and impact would be known. Virtually every post-hardcore band who came in their wake owed them everything. A good few of those later labelled as emo did too.

Success to me is never about figures, red carpets and limos

Shaun Lopez

“Like many good bands before us, we disbanded before there was any kind of success,” Lopez later lamented. “I’m always amazed when bigger current bands mention Far as a major influence, because at the time of our existence we seemed like such outcasts: too melodic for the hardcore kids, not hard enough for the metal kids. But success to me is never about figures, red carpets and limos. It should be about making music that you can look back on and be proud of what you did. In that respect, Far was a success.”

“When Water & Solutions was done,” says Matranga, “I had a bit of sadness realising that we’d made probably the best Far album that we ever would. We were a mess, and on that record, I think it was a beautiful mess.”

That beautiful mess charmed its way into the hearts of more people in the band’s absence. The members of Far would go onto other projects and achieve success on their own terms in all kinds of worthy and admirable ways. But it was the songs they recorded in New York City that spring that would define them. Years later, when relations had thawed, they found a moment to take a brief belated bow.

Their 1,000-cap reunion show at ULU in London in 2008 was their biggest attendance ever. In 2010 they put out a new album, At Night We Live, managing the rare feat of adding to their legacy without fundamentally changing what it was that people loved about them first time around. The comeback campaign kicked off with a novelty tongue-in-cheek cover of Ginuwine’s R&B track Pony. Bizarrely, that’s now what a lot of people know them for. Those who dig deeper, however, will find ‘fires left ablaze’, even 25 years later.

Formerly the Senior Editor of Rock Sound magazine and Senior Associate Editor at Kerrang!, Northern Ireland-born David McLaughlin is an award-winning writer and journalist with almost two decades of print and digital experience across regional and national media.