"There were a helluva lot of drug issues and bad feeling in the air": How doomed Beach Boy Dennis Wilson made his solo masterpiece Pacific Ocean Blue

Beach Boys drummer and singer Dennis Wilson made a much-loved cult classic with 1977’s Pacific Ocean Blue – then spiralled out of control

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

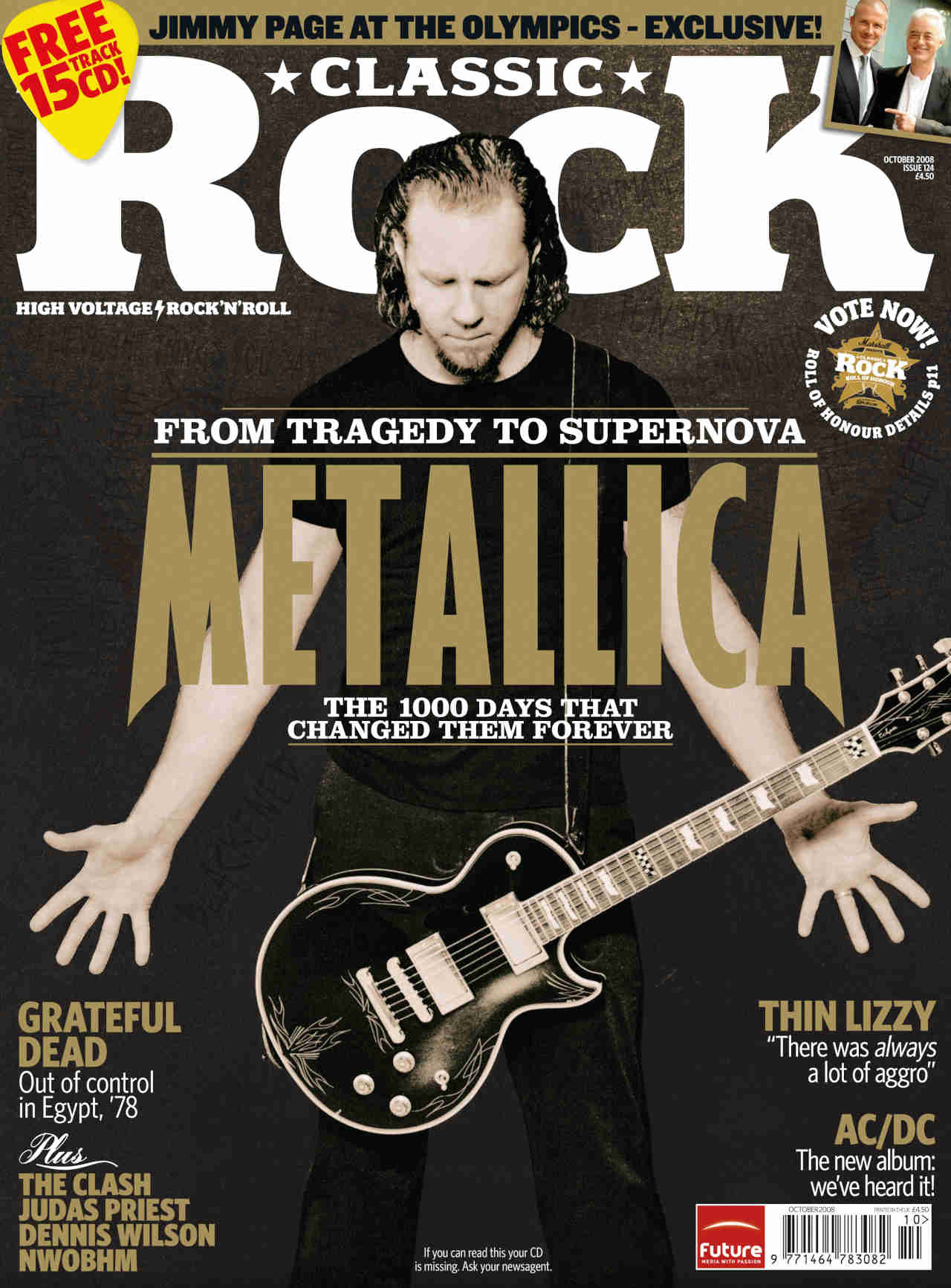

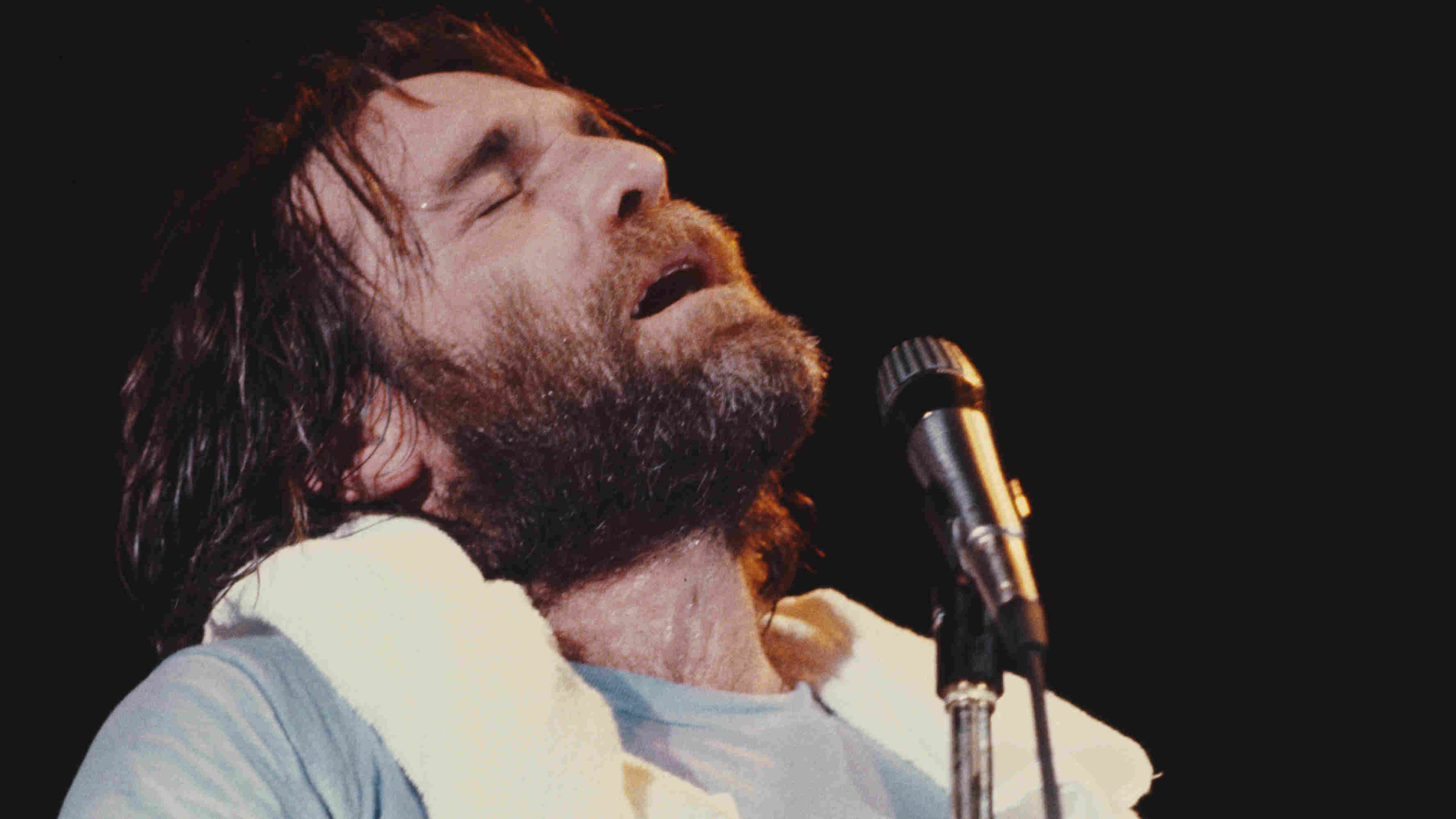

Dennis Wilson made his name as a member of the Beach Boys. But in 1977, he broke away to record a lone solo album, Pacific Ocean Blue. In 2008, Classic Rock looked back on the making of a cult classic – and Wilson’s tragic death six years later.

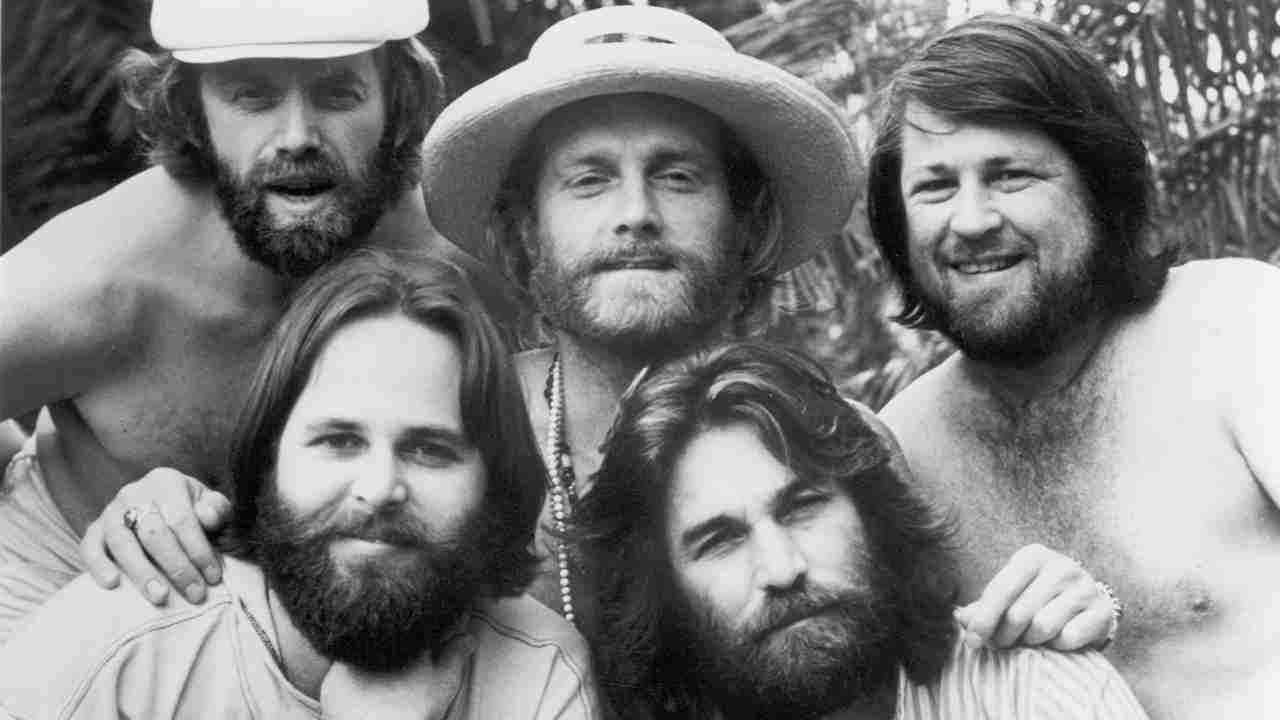

Dennis Wilson, second born of the famous Wilson brotherhood, was the soul of the Beach Boys. Sure, Brian Wilson was the genius, the mastermind without whom they’d never have got out of their Hawthorne garage. Pudgy Carl was the organiser. Cousin Mike Love had the ambition and drive while schoolfriend Al Jardine represented their moral, clean cut code. Dennis was the real deal.

The favourite son of tyrannical father Murry, no one ever imagined Dennis amounting to much other than drumming and exciting the Beach Boys’ female fans. A rugged surfer dude, he epitomised their image but was never the quickest witted fellow. “My little brother Denny? He’s a little dumb,” Brian told anyone who asked.

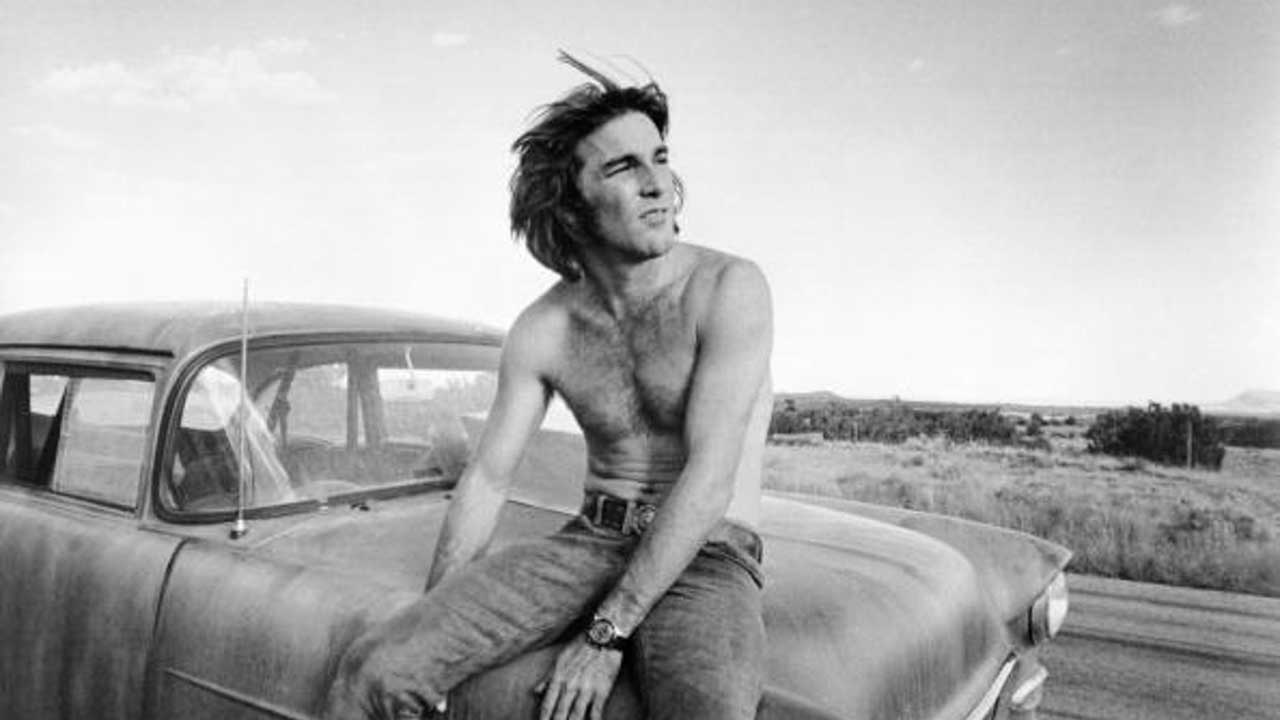

At least that’s how it was in the 1960s. In the 1970s everything changed. Dennis became the enigmatic, philosophical Beach Boy who released a solo single with Daryl Dragon as Drumbo (geddit?), starred in the cult buddy road movie Two-Lane Blacktop with hip Apple singer James Taylor and then broke out of the fold. His 1977 solo album, Pacific Ocean Blue, is now given the same reverence as landmark Boys recordings like Pet Sounds, Surf’s Up and Holland.

The genesis of Pacific Ocean Blue begins during a typically tumultuous time in the Beach Boys’ bizarre career when Dennis is hiding out with some groupies in Seattle. Despite the brilliance of Holland, recorded in Baambrugge in the Netherlands due to chronic tax problems with the IRS, the Beach Boys have hit a slump. Not only are they broke, they’re playing greatest hits medleys for students who despise them. Unable to fuse their new progressive music with a back catalogue that then seems terminally old, one night in 1972 they support the Grateful Dead and are booed off.

Shaken, Dennis calls up an old pal, a 29 year old Italian American all-rounder called James William Guercio. He’s shared stages with the Beach Boys as bass player for Chad & Jeremy, going on to play lead guitar for Frank Zappa, then manage Chicago and Blood Sweat & Tears. He has also directed and produced and written the score for the awesome cops and bikers movie, Electra Glide In Blue, a cynical rebuttal of the whole Easy Rider mythology.

“The Beach Boys were baby shit when Dennis called,” Guercio tells Classic Rock from Caribou, his Colorado ranch-cum-recording empire. “No one’d touch ’em. It was frustrating to see ’em fuck up. They were getting five thousand a night. No sell outs. No production. No show plan. I had Chicago making $100,000 a night, and selling millions of records. I knew that wasn’t right.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Dennis pleaded with Guercio to move in and usurp then manager Nick Grillo. They worked by stealth. First Jimmy replaced the South African bassist Blondie Chaplin, then he took over the controls working on an 18-month strategy that restored the Beach Boys status, enabling them to reclaim what he called “the legacy of American music”.

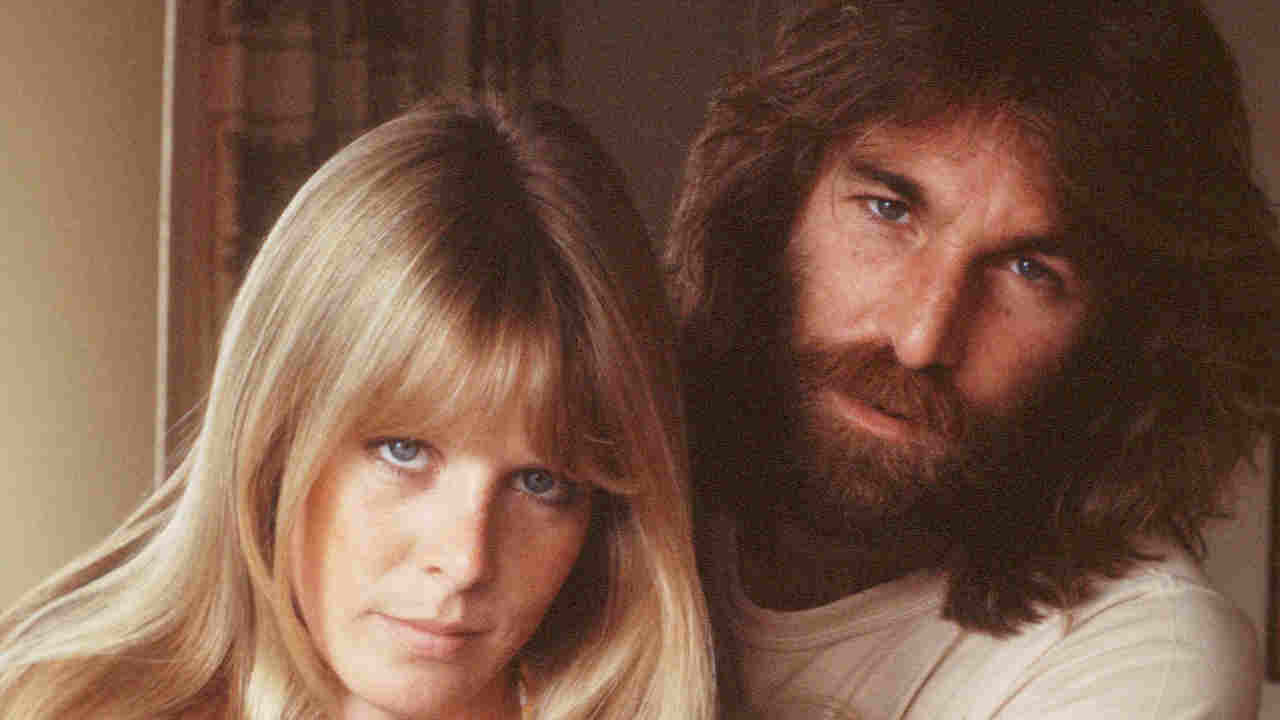

By 1975 Guercio’s strategy of playing 168 consecutive one-nighters paid off. The Beach Boys supported Chicago and ended up blowing them away. There were repercussions. “One night I’m looking round and the Chicago wives and girlfriends are on one side of the stage, the Beach Boys women are on the other side – as usual – except one person has moved across,” Guercio chuckles. This was Karen Lamm, estranged wife of Chicago vocalist Bobby Lamm.

“There was obvious tension. Dennis was insisting ‘Man, I love this chick, she’s so great’ – which she was, everybody wanted a piece – and there’s Bobby glowering and pretending it’s cool. It got tense. Chicago trashed their dressing room while the Boys’ room is a haven, with Mike Love doing his Maharishi shit. There were a helluva lot of drug issues and bad feeling in the air. I wasn’t committed to Chicago. I was committed to Dennis.”

With his new muse and soon-to-be third wife Karen Lamm-Wilson goading him on, Dennis went to work. In between the fisticuffs and slanging matches that typified his relationship with her he began to play Guercio cassette demos and gave him impromptu live renditions of his new melodies “in hotel bars, on aeroplanes, at soundchecks. I heard it all”.

Guercio ordered Dennis to finish the material, bringing in mutual friend Gregg Jakobson to provide lyrics and structure, and signed the pair to his Columbia-bankrolled label Caribou in the summer of ’76. Dennis’s super subtle songwriting had blossomed. The templates were struck on Be With Me – for the 20/20 album – and Forever – on Sunflower. He’d contributed Only With You and Steamboat to Holland, then soared towards orchestral nirvana with Cuddle Up and Only With You for the overlooked Carl And The Passions.

The dreamlike quality of these songs and the 76/77 sessions that became Pacific Ocean Blue represented Dennis’s soulful side. By contrast he was a notorious hell raising womaniser who’d lost his virginity aged 12 and christened himself ‘The Wood’ – always hard and ready for action.

It was that Dennis who opened the door of his rented house on Sunset Boulevard on an innocuous day in spring 1968 to find one Charles Manson and Family sprawled about. Manson and his army of acid popping nubiles moved their schoolbus, emblazoned ‘Hollywood Productions’, onto Dennis’s lawn and took over with a lethal mix of drugged debauchery, orgiastic sex and mumbo jumbo.

They infiltrated themselves so thoroughly into Dennis’s world that the Beach Boys were persuaded to record one of Manson’s ditties, a macabre number presciently entitled Cease To Exist. Wilson and Jakobson enjoyed the sickness but were savvy enough to change the title to Never Learn Not To Love, and adapt the key line to ‘cease to resist’. They had no trouble getting the Boys to put it on the B-side to their Bluebirds Over The Mountain single. Charlie was weird but he knew a lot of girls.

Dennis referred to Manson as ‘The Wizard’. He told England’s Rave magazine “He’s got so many great ideas… he’s fascinating… a real thinker. I like him a lot.” He was less enamoured when Manson one day pulled a knife on him in his own kitchen. “I could kill you now Dennis,” his house guest gloated. “Go ahead then muthafucker,” replied the host, promptly collecting a few belongings and moving out to a hotel.

Although Dennis managed not to provide testimony following the Tate/LaBianca murders carried out by the Manson Family he did tell reporters “I want nothing to do with that man. He’s a sick fuck. A major arsehole… I mean he cut their tits off and everything.”

Not a nice Wizard.

A decade later Dennis had problems of his own, exacerbated by a prodigious vodka and cocaine habit and his volcanic life with Karen. During early recordings of Pacific Ocean Blue she unloaded a pistol given him by Guercio into the side of his three day old black Mercedes. “That shook him up” Guercio laughs. “‘Look what she did, man! Three bullets in the passenger side.’ Then he forgot it. They were both, er, a little crazy.”

Another time he ignored her she threw a brick through the plate glass doors of the Beach Boys Brother Studios. It was recovered, tied with ribbon and framed above the legend ‘The Karen Lamm-Wilson Memorial Brick.’ When she wasn’t pouring bottles of booze over the console, Karen was more helpful; she added vocals to the album and co-wrote two songs.

Recording POB wasn’t easy. Guercio and Jakobson recall flushing Dennis’s stash down the toilet with alarming regularity. “But it was often a real pleasure too,” recalls Gregg. “During daylight hours he was more or less coherent and conscientious. He wasn’t big on writing words, so he needed collaborators, but his music was fantastic and he had plenty of lyrical ideas.”

An essay submitted on a favourite topic at Hawthorne High School in 1961 – he was expelled at 16 for throwing a screwdriver at a fellow pupil – illustrated his naive poetic sensibility. “Sports car racing is very dangerous” he wrote. “Just think, you’re going about 120 miles per hour down a curved mountain road, then you have to make a hard right or left. The main thing is you have to keep your eyes on the road, not in the deep blue sky.”

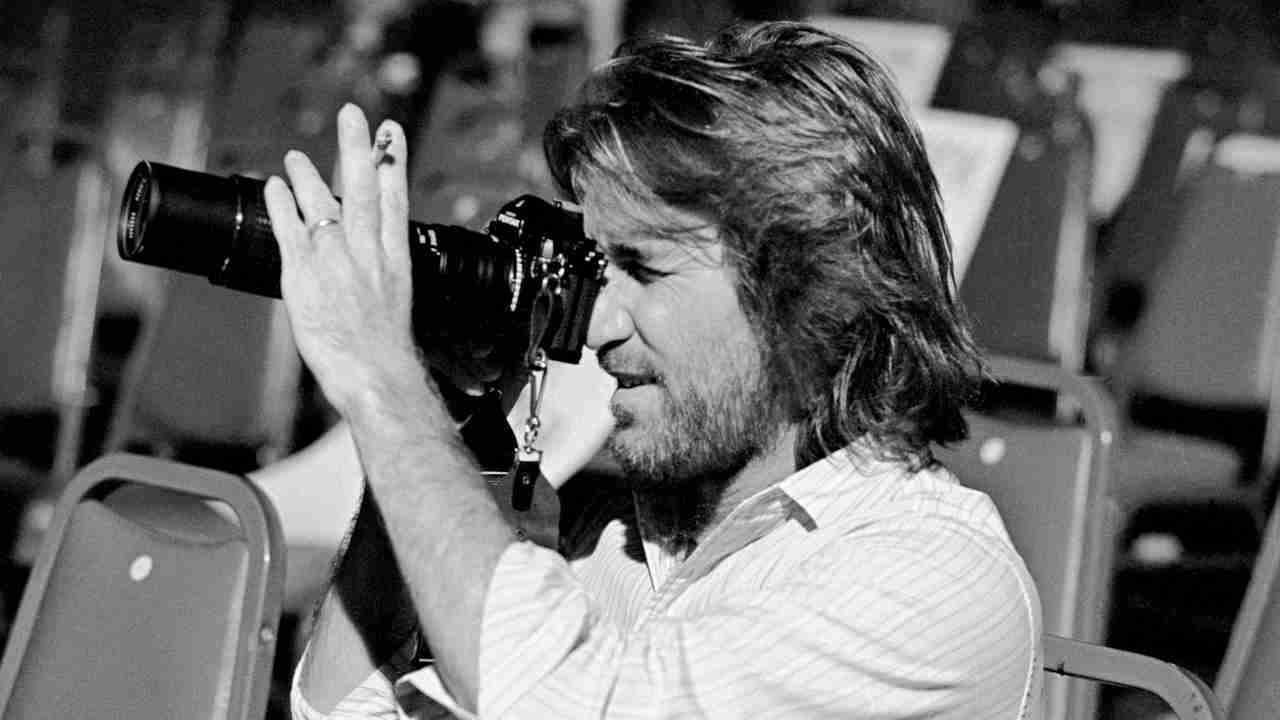

Released in September ’77, Pacific Ocean Blue (working title Freckles) developed his nature boy character. Art direction was provided by old friend Dean O. Torrence (of Jan & Dean fame). They went to Maui for the shoot. “Both the setting and Dennis were very photogenic,” Torrence remembers. We went for an everyday, snapshot approach. He was a pal so it was like a vacation until Karen turned up. She was just around, like Yoko Ono. A real coupla handfuls. They both were. One night she told Dennis I was having an affair with her. Which I wasn’t. He liked her intensity and the chaos. Made him feel in love.”

The beatific tone of the music informed Torrence’s approach. “He always had a dommed surfer look, kinda glazed, wanting to be someplace else, even when he’s in paradise. But he was also heaps of fun. We shared a Go-Karts business, Race ’Em, Break ’Em & Wreck ’Em. He liked living on the edge, or over the line was even better.”

Pacific Ocean Blue gained rave reviews on release, selling 200,000 copies – much to the Beach Boys annoyance. But Dennis didn’t find fulfilment. He continued writing and recording in a frenzy for what became Bambu – unreleased until 2008 – named after his favourite rolling papers, although by now Jakobson was exhausted and left the technicalities to engineer John Hanlon.

On New Year’s Eve 1977 Dennis and Karen took heroin together for the first time, beginning a woeful trajectory that would see him being kicked out of the Beach Boys. Frequent spells in rehab couldn’t turn him around. He divorced Karen, remarried her, divorced her again and then shacked up with wife number five, Mike Love’s daughter Shawn.

Throughout the early 80s, Dennis was drifting in and out of relative destitution. Large royalty cheques were squandered in week long drugs and drink binges, short lived sports cars and ne’er do well hangers on. He was forced to sell his beloved boat, the Harmony, weeping when it went at knock down in auction.

A few weeks after his 39th birthday Dennis was back on the water on friend Bill Oster’s boat – the Emerald – moored at Marina Del Rey. It was December 28th and the Pacific Ocean was chilly and grey. By late afternoon Dennis was stoked. He’d downed a bottle of his favoured Delray vodka and gone diving, fully clothed, hoping to recover possessions he’d thrown overboard during the turbulent last days with Karen.

After three fruitless attempts he emerged clutching a smashed silver framed photo given to him as a wedding present by the man he called Jimmy G. “It was a beautiful Tiffany piece I gave them along with the silver handled 9mm pistol she shot up his car with,” says Guercio. “He was so ecstatic he dove in again.”

What happened next, according to the story Carl Wilson told Guercio, is that “Denny hit his head on the bottom of the boat and got concussed. He was such a good swimmer and such a jock, even though he was alcoholic. He came up three times gasping for help. The others thought he was goofing around. He wasn’t.”

Against the wishes of Shawn, Dennis’s ashes were buried at sea, following the intervention of former girlfriend Patti Reagan. In a moment of black farce Shawn requested the Police song Every Breath You Take be played at the memorial service because it was Dennis’s pop song du jour. That idea was nixed and Farewell My Friend from Pacific Ocean Blue blew its haunting melody over the weeping mourners

And so the death of a Beach Boy came in a watery grave, although Dean Torrence wasn’t overly surprised. “Actually, I thought he’d OD, or crash his car. Having surfed, sailed, fished and drag raced on Daytona Beach with him all those times I didn’t think he’d drown. But he wasn’t a happy man. The odds were against him in life and in love. The thing is, if you keep on stomping on the floorboards, one day they’re going to give in.”

Originally published in Classic Rock 124, September 2008

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.