"The sun will rise and fall, and BB King will play the blues": The incredible life of BB King

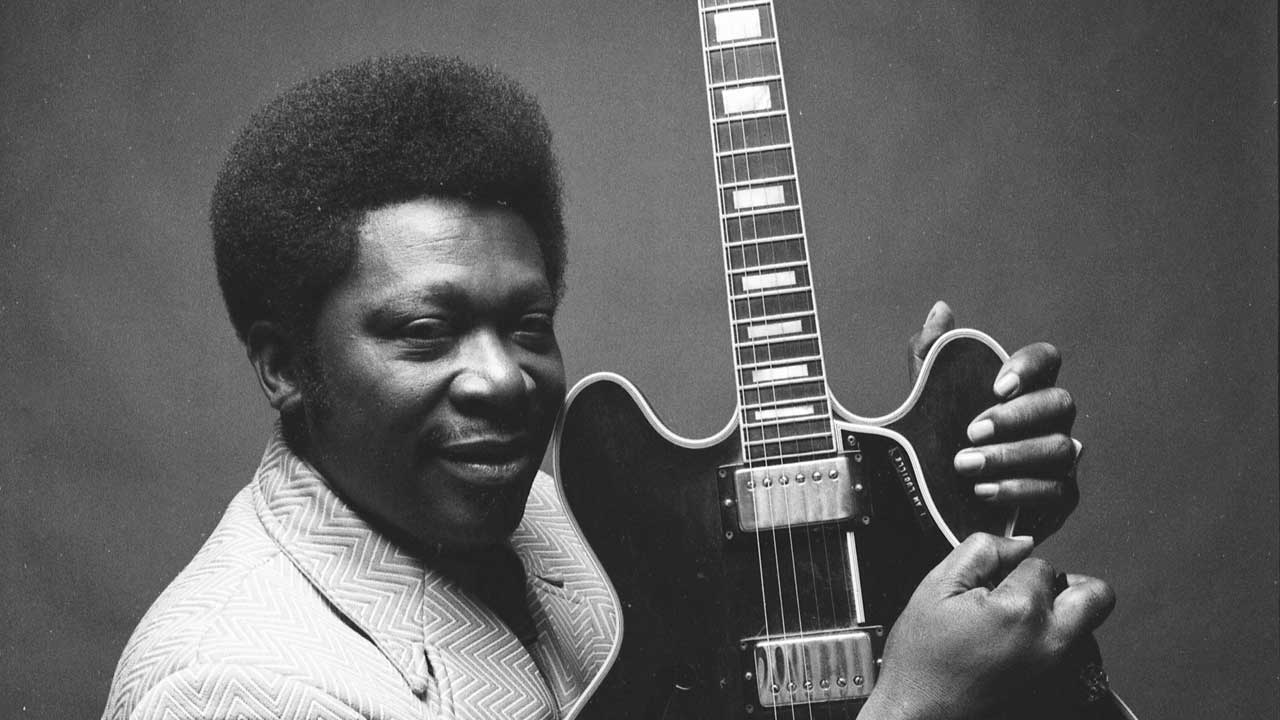

BB King was the greatest bluesman the world has ever seen. We look back at his life, with a little help from his friends

Among the flood of tributes that followed the news of BB King’s death was one from Barack Obama. “The blues has lost its king and America has lost a legend,” declared the US President. “No one did more to spread the gospel of the blues. He gets stuck in your head, he gets you moving, he gets you doing the things you probably shouldn’t do.”

Obama happened to be talking from direct experience. In February 2012, while hosting an all-star TV celebration of the blues in the East Room of the White House – titled In Performance At The White House: Red, White And Blues – BB King and Buddy Guy coaxed him into taking the mic from Mick Jagger. Taken aback but somewhat bashfully rising to the challenge, the President then sang the first verse of Robert Johnson’s Sweet Home Chicago, trading a line with King before handing back the reins. King, meanwhile, remained stage front, his guitar across his chest and a mischievous grin on his face.

For all its geniality, the episode served to illustrate the kind of benign power that BB King was able to exert wherever he went. His reach went far beyond the blues he adored so much, making him a transcendent figure in popular culture. This was a man who was as likely to serenade Popes and Presidents as he was Homer Simpson or the cast of Sesame Street. King’s reputation only grew with the passage of time. In later years, as his frame widened, it was almost as if his body morphed into a physical symbol of his own legend, impossible to ignore and larger than life itself.

BB’s blues, like so many of his generation, were rooted in the cotton plantations of Mississippi. Yet he was able to bring a universality to his music without sacrificing what made his guitar-playing so unique: his bell-like tone, extraordinary phrasing and distinct vibrato. John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters were fellow giants of the electric blues, but neither of them achieved the same level of acclaim as BB King. He was the blues’ first, and last, true superstar.

The outpouring of affection that trailed King’s death, aged 89, was a measure of the esteem in which he was held by fans and colleagues alike. Over 1,000 people queued to view his guitar-flanked casket at the Las Vegas public memorial at the end of May. It signalled the beginning of a week-long series of commemorations, including a procession down the length of Beale Street in Memphis, where King first went as a 20-year-old in 1946, and ending with his burial in his Mississippi home town of Indianola.

Of the eulogies offered by many of Hollywood’s biggest talents, Morgan Freeman was the most impassioned. King’s death, he said, was not only a loss to humanity, but had also “created a hole in the universe.”

Longtime devotee Eric Clapton took to Facebook to address his 9.5 million followers in a video message: “He was a beacon for all of this kind of music, and I thank him from the bottom of my heart.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The Stones, Buddy Guy, Slash, Richie Sambora, Gene Simmons, Lenny Kravitz, Bonnie Raitt and Carlos Santana (who said King’s “one-of-a-kind sound was an inspiration to an entire generation of musicians, including myself”) were similarly effusive.

“BB’s audiences were always captivated by the intensity and honest emotion of his interpretations,” says British veteran John Mayall, whose Bluesbreakers proved a hothouse for King disciples Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor during the 60s. “He was one of a few great blues musicians who appealed to both black and white audiences on a large scale. I think his reputation for being a major person in popular music also can’t be understated. His music crossed all borders and categories. His voice and guitar playing will never be matched.”

Born to sharecropper farmers in 1925, Riley B King had music in the blood. His mother’s cousin was Delta bluesman Bukka White and, as a child, King began singing gospel in the church choir in the Mississippi town of Kilmichael. It was there that he was taught his first rudimentary guitar chords by music-loving preacher Reverend Archie Fair. He would soak up the sounds of Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson at the home of his Aunt Mima, who played records on a Victrola machine.

Then, in 1935, when King was just nine, his mother suddenly died (he later cited A Mother’s Love as his own personal favourite among his vast catalogue, because it reminded him of her so much). With his parents already estranged, he stayed with his maternal grandmother until, five years later, she too passed away.

The early 40s saw him move to Indianola, which he came to consider his spiritual home, where he took a job as a tractor driver and joined a new vocal outfit, The Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers. But the blues kept calling him back. King began busking for change on street corners with a 15-dollar guitar. Things took a turn in 1946, though, when he totalled the tractor and, rather than face his boss’s wrath, headed to Memphis to seek out cousin Bukka.

For the next 10 months, White took him under his wing and began to teach King the art of the blues. King’s apprenticeship wasn’t easy. In particular, he struggled to emulate White’s ability to play slide guitar. The sound it made, he recalled years later, exerted a peculiar, elusive fascination, similar to the tone of another favourite player, Leon McAuliffe, the steel guitarist for Bob Wills & the Texas Playboys. King’s ad hoc solution was to grip the neck, grab a note and “trill my hand”. This provided him with his own form of vibrato.

“BB said he tried to learn how to play the slide, but he could never perfect it,” recalls Buddy Guy, one of King’s closest friends and another iconic blues figure. “So he learned how to bend the strings to try to sound as much like the slide as he could. And boy, I have to thank him for what he did. We were friends for 50 years or more and I used to tell him: ‘Man, it all came from you!’”

King made a brief return to Indianola the following year, where he convinced his wife to settle with him in Memphis. By 1948, he was back on Beale Street, the blues thoroughfare that served as the musical hub of the city’s black population.

“When I would hang around Beale Street it was kinda like a community college,” King told me in 2009 for Classic Rock. “I had a chance to learn many things from people who were just sitting out in the park, where it was warm. Some would play, some would dance and some would do many other things I don’t do. I learned quickly, after I left Mississippi and went to Memphis, that I was nothing like what a lot of people said I was. When I heard other people play and sing, I thought, ‘Ah, they’re making mistakes, too’. So I was just trying to do what I do, play like I play and hope that people liked it.”

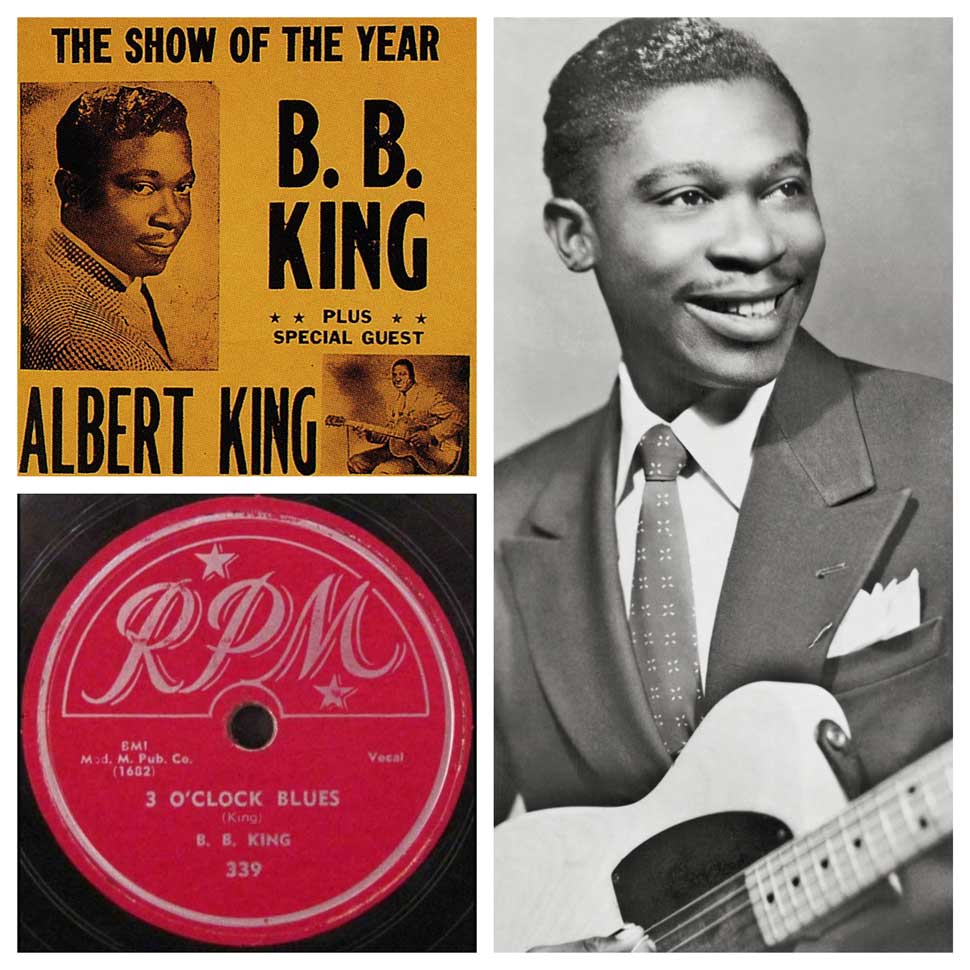

King’s big break arrived when he secured a spot on Sonny Boy Williamson’s local radio show, which led to a steady gig at the Sixteenth Avenue Grill in West Memphis. Soon he had his own slot on black-owned radio station WDIA, where his popularity spiked even higher. Searching for a user-friendly handle, the station’s publicity man dubbed him “Blues Boy” King, which eventually became, quite simply, “BB”.

His first recordings were for Bullet and RPM (where his producer was Sam Phillips, future founder of the Sun label), but none of them made an impression. It wasn’t until early 1952 that his version of Lowell Fulson’s Three O’Clock Blues topped the R&B charts for five weeks. Received wisdom has it that Ike Turner featured on the song.

“It’s a big mistake that people think Ike Turner played piano on Three O’Clock Blues,” he stated, a little wearily. “People write what they want about me and put the wrong players and dates in. The guy who played piano was John Marshall Alexander Jr, who later became Johnny Ace.”

More successes arrived later that year with You Know I Love You and Story From My Heart And Soul. Suddenly, King was selling out theatres across the US and saw his earnings jump dramatically, pulling in around $2,500 per week. This upturn in fortunes set in motion a punishing touring regime that would continue for the rest of his life. By 1954 he was averaging nearly 300 gigs a year with his 13-piece band. His career may have been flying, but his marriage, as a result, crashed and burned.

It’s a curious fact that two of King’s most memorable recordings were the direct consequence of divorce. Woke Up This Morning was written after his first break-up, and his definitive cover of Roy Hawkins’ The Thrill Is Gone, cut in 1969, followed after the demise of a second marriage. By then, King had become a figurehead for the new breed of white blues-rockers in the US and UK.

This crossover status was the result of his deification by the likes of Mike Bloomfield (who admitted to copping BB’s licks on the first Butterfield Blues Band album), the Stones and Eric Clapton. In his autobiography, Clapton wrote that King was “without a doubt the most important artist the blues has ever produced… In terms of scale or stature, I believe that if Robert Johnson is reincarnated, he is probably BB King.”

Jimi Hendrix was also a fan. On the night of Martin Luther King’s assassination in April ’68, he and Buddy Guy jammed with BB at an all-night blues club, raising money for the Civil Rights man’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“In fact, I’m still mad with Jimi Hendrix today,” laughed King in 2009. “He brought a tape recorder along and asked us if he could tape it all. He was supposed to give me a tape, but he never did. When I leave this earth, if there’s any way I can find him I will fuss at him about my tapes. I’ll give him a hard time! What was he like to play with? In his latter days I thought he was the number one rock’n’roll guitarist, with Eric [Clapton] right behind him.

"There were a lot of British guitarists I liked. If it had not been for some of those musicians, doors would never have opened for me. I toured with the Stones in 1969 and finally got a chance to record with them. I remember opening for the Stones when we played Baltimore. A white lady came to see me afterwards and asked if I’d ever made any records! I guess I’d made twenty-five or thirty by that time. She said she had some teenage children and they liked what I was doing. Even though it was nice of her, it was funny because I’d been playing all this time.”

This crossover success included one memorable show at the Fillmore West in June 1968. King was brought to tears when the predominantly white audience gave him a standing ovation as he walked on stage. A year later, two decades after his first single, he made his network TV debut on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show. By 1971, The Thrill Is Gone had made such an impression that it earned King a Grammy. It was to be the first of 15 during his lifetime.

Just as Clapton had “Blackie” and Keith Richards had “Micawber”, so BB King named his guitar ‘“Lucille”. The genesis of the title, as King told it, dated back to a show at a small club in Twist, Arkansas, in the winter of 1949. During the evening, two men started a fight, knocking over the barrel of kerosene that was used to heat the hall. The place burst into flames and everyone made for the exits. It was only when he was outside, however, that King realised he’d left behind his cherished Gibson guitar. He dashed back in, risking his life, to retrieve it.

The next day he discovered that the skirmish had broken out over a girl called Lucille. King duly christened his guitar in her honour, “to remind me never to do a thing like that again”. Alas, the original Lucille was stolen from the trunk of his car in Brooklyn, not long after the fire. King tried to track it down.

“I never did find out who’d done it,” he explained. “We put out bounties for anybody that would bring it back. Even after I got to be popular, we put rewards out – $15,000 back in the 50s, a lot of money then.”

There have been several Lucilles in King’s life since, all of which became synonymous with his ringing, single-note sustain that served as a trademark. “I did give one of my Lucille guitars to Pope John Paul II one time,” he said, referring to the occasion when he played at the Vatican in December 1997.

“A lot of people don’t know it, but before becoming Pope he was a poet and guitarist. He wasn’t necessarily a blues player, but most people who play guitar are, sooner or later, gonna hit a blue note. You can’t miss it. When I was at the Vatican, I was trying to give one of his aides the guitar, but the Pope took it himself. He was a very wise man and one of my favourite people.”

If the 60s found King finally playing to the masses in the US and Europe, the next decade saw his stock rise on a global level. Perhaps his most high-profile appearance came in October 1974, when, along with James Brown and Lloyd Price, he was invited to Zaire to perform as part of the pre-fight ceremony for the Rumble In The Jungle, the world title bout between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman.

“I got to know Muhammad Ali pretty well, right after he became Olympic champ [1960, as Cassius Clay],” King recalled. “It was a lot of fun. I’d been to Africa before, but not the city of Kinshasa. Something happened to George Foreman and they had to put off the bout for another day or two, so I couldn’t stay because I had other commitments. But I was there for the recording and taping of the movie part. I don’t know if Ali cared for my music, but he certainly knew me. Every time we’d meet, he’d say: ‘Old BB King, you ain’t as dumb as you look!’”

King’s influence, meanwhile, continued to spread. One of his most enduring albums, at least for new US guitarists like Warren Haynes, later of The Allman Brothers Band and Gov’t Mule, was 1970’s Indianola Mississippi Seeds.

“When the blues guys I loved started making more contemporary records, combining soul with blues, they kind of got into jam territory,” says Haynes. “Freddie King did it with Burglar [1974], Albert King had Born Under A Bad Sign [1967] and BB King did it on Indianola Mississippi Seeds. Suddenly there were wah-wah pedals and rock musicians accompanying blues musicians side-by-side. I learnt so much. The only guitar teacher I ever had was a blues guitarist, who told me that if I only ever listened to Albert King and BB King I’d be studying for the rest of my life. I learnt a lot from that statement.”

The 80s signalled the beginning of King as an institution and the foremost ambassador of the blues. He was presented with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987, and inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. U2 brought him on board for 1988’s Rattle And Hum, duetting with Bono on the pumping electric blues of When Love Comes To Town. Issued as a single, it was King’s first UK Top 10 hit, in April ’89.

On hearing of his death, U2 paid tribute at a gig in Vancouver by performing the song for the first time in 23 years. In the 90s, King’s cultural and commercial reach was such that he was able to open his own 350-seater nightclub on his beloved Beale Street in Memphis: BB King’s Blues Club. Other branches followed in LA, New York, Connecticut, Nashville, Orlando and Las Vegas. In 1990 he made the top three on Billboard when he appeared on The Simpsons’ first offshoot album, The Simpsons Sing The Blues (for the record, he joins Homer and the Tower Of Power horn section for Born Under A Bad Sign).

It was at this time that he invited a 12-year-old blues prodigy from New York to open for him at shows across the US. For the boy in question, Joe Bonamassa, whose favourite album was King’s Live At The Regal, it was beyond his furthest imaginings. Bonamassa recalls the thrill of hearing the familiar intro delivered by King’s nephew, Walter: “‘Ladies and Gentlemen, the King of the Blues, Mr BB King!’ That, combined with the fast shuffle and the horn stabs as BB walked on stage, was enough to convince this kid on May 24, 1990 that a life in the blues was for me."

For Bonamassa, King’s loss was incalculable. He calls him “a man larger than life, who was a constant, something you can set your watch to. The sun will rise and fall, and BB King will play the blues… He defined the blues, he was the blues.”

King’s exhaustive touring schedule continued well into the new millennium. His relentless desire to play an inspiration for others. “BB was a really sweet, gracious individual,” says Slash, “and someone who I admire for silly things – like the fact that he toured and lived on his tour bus. He basically worked all the way until his death, which if I was gonna go, that’s how I’d want to go.”

The 00s was a decade that saw him receive further honours – a Presidential Medal of Freedom, a National Heritage Fellowship Award, a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame – but one of his proudest moments came with the opening of The BB King Museum and Delta Interpretive Centre in 2008. Housed in Indianola and dedicated to preserving King’s legacy, its aim was “to celebrate the rich cultural heritage of the Mississippi Delta, and to promote pride, hope, and understanding through exhibitions and educated programs”.

“It’s sort of a centre of learning, it’s not just about BB King,” he said, in a tone that was typical of the man’s humility. “I was sorry they called it my museum, though I think they were trying to honour me because I’m from the Delta. But we try to teach people about the origins of this kind of music and how we think it began. So we talk about all the people we know who played blues and jazz.

"One of the greatest saxophone players ever, a guy called Lester Young, was born in Mississippi, too. There weren’t a lot of white people who played just blues, like Jimmy Rogers did, but a lot of them were influenced by Mississippi. I hear today that everybody that played blues came from, or near, the Dockery Plantation. But I never knew about that. When I look now at where I was born, it really wasn’t more than a hundred miles away.”

King was forced off the road only at the end of last year, when ongoing health problems marked the end of a touring pattern that had run for over 65 years. High blood pressure and diabetes meant he was hospitalised for the duration, and he died in his sleep after what doctors surmised was a series of minor strokes. His unofficial status as Ambassador of the Blues was something he wore with grace and not a little satisfaction.

“I look at it this way,” he said. “I think Muddy Waters was the Godfather and since then, I don’t think anybody has carried the blues further than I have. When they call me the Ambassador, I’m very proud of that title.”

With Buddy Guy, Otis Rush and James Cotton still with us, King wasn’t quite the last of the great pre-war bluesmen. But he was the most supreme, and the most influential, of them all.

“BB King is the best player I’ve ever been on stage with,” says Guy. “With regards to what Mike Bloomfield played, or Clapton, Beck or whoever, BB King is the cause of the price of what the guitar is today. He created it. I haven’t seen anybody yet who can make a guitar vibrate like he does.”

“He’s probably my top blues influence – his sound and his phrasing,” Slash affirms. “He was much a mentor as a hero to me.”

But above all, King was a humanist. And, as a black man raised amid a Southern climate of segregation and intolerance, he was all too aware of his position as a role model for minorities everywhere.

“I had some bad things happen to me in my life, but people don’t think too much about whether they are doing others wrong,” he offered. “A lot of those people would apologise if they had the chance, one on one. I felt bitter about it for some time, because I only thought about the people who treated me badly. Those people were always reminding you of what colour you were, that you were the son of a slave. I always felt like I was a second-class citizen. Regardless of what you said or did, it never seemed to be enough.

“But one of the highlights of my life,” he continued, “was when I was invited back to my home state of Mississippi by the Governor at the capital [in 2005, King was honoured as a favourite son by the Mississippi Senate and House of Representatives]. For about a whole hour, all the legislators stopped doing their state business so they could talk to me. It was so touching that I cried. I finally became a citizen, rather than a second-class one. In the US today, we have a black President, which I never thought would happen in my lifetime. I’m just so glad I lived this long.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 212, published in June 2015.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.