Bat Out Of Hell: The turbulent life cycle of a rock’n’roll phenomenon

From its stage show origins to a global smash hit album, Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell has returned to its roots... as a West End musical

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The theatre is crowded and the audience rapt as Jim Steinman approaches the girl.

“On a summer night,” he says, “would you offer your throat to the wolf with the red roses?”

“Yes,” she replies.

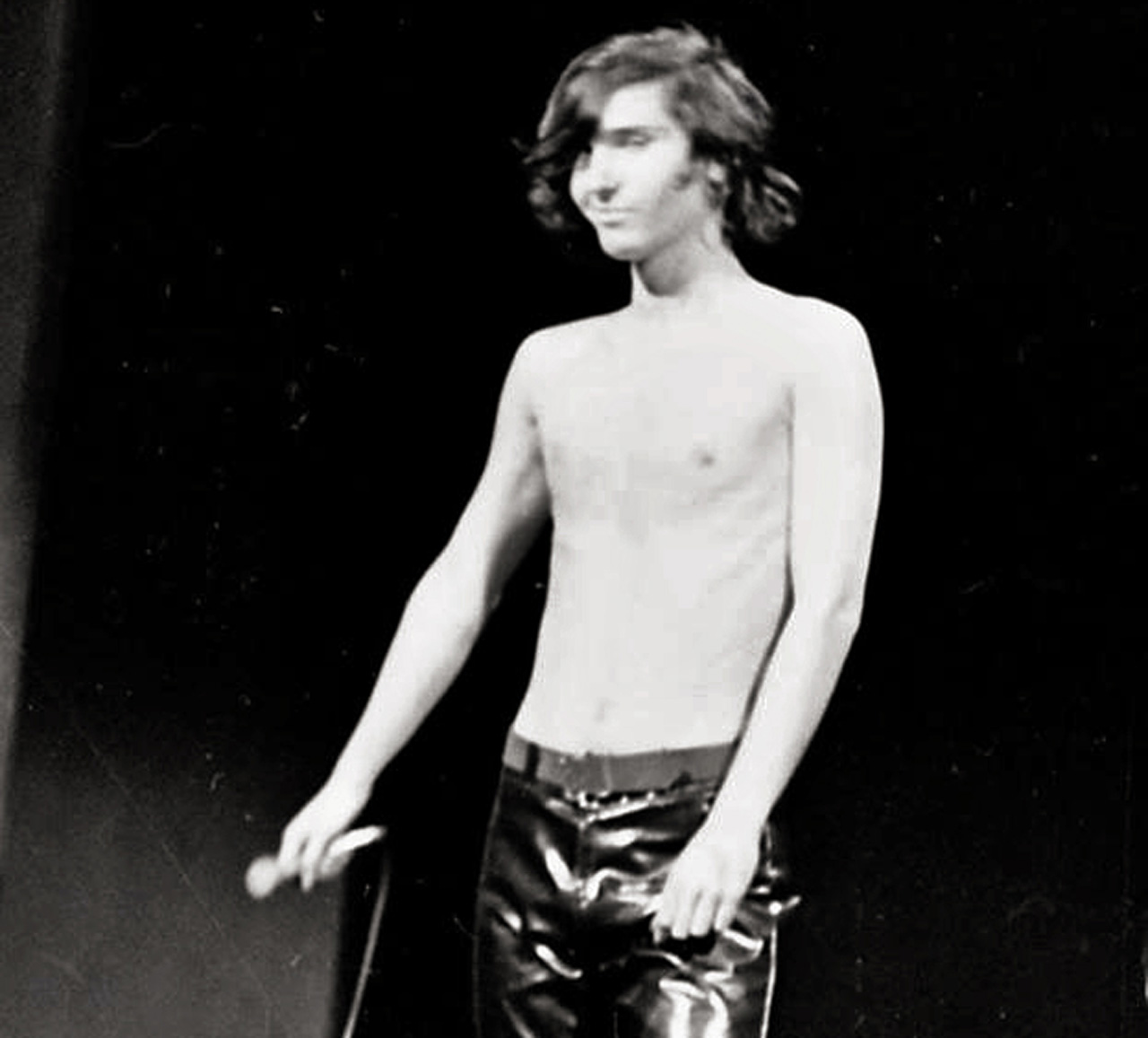

It’s April 25, 1968, and the first performance at Amherst College, Massachusetts of The Dream Engine, a rock musical written by Jim Steinman, in which he also appears as Baal.

“Again,” says Baal. “On a hot summer night, would you offer your throat to the wolf with the red roses?”

“Yes,” says the girl. “Then you’re ready,” says Baal.

As The Tribe prepare her initiation, he begins to recite a nursery rhyme. “Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross…”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I think Steinman’s just brilliant,” says a laughing David Sonenberg, a manager and lawyer who has worked with both Jim Steinman and his vocal representative Meat Loaf since the mid-1970s. “He’s also crazy! I can tell you Steinman stories for days…”

He can indeed tell me Steinman stories for days – but only off the record, which is a shame.

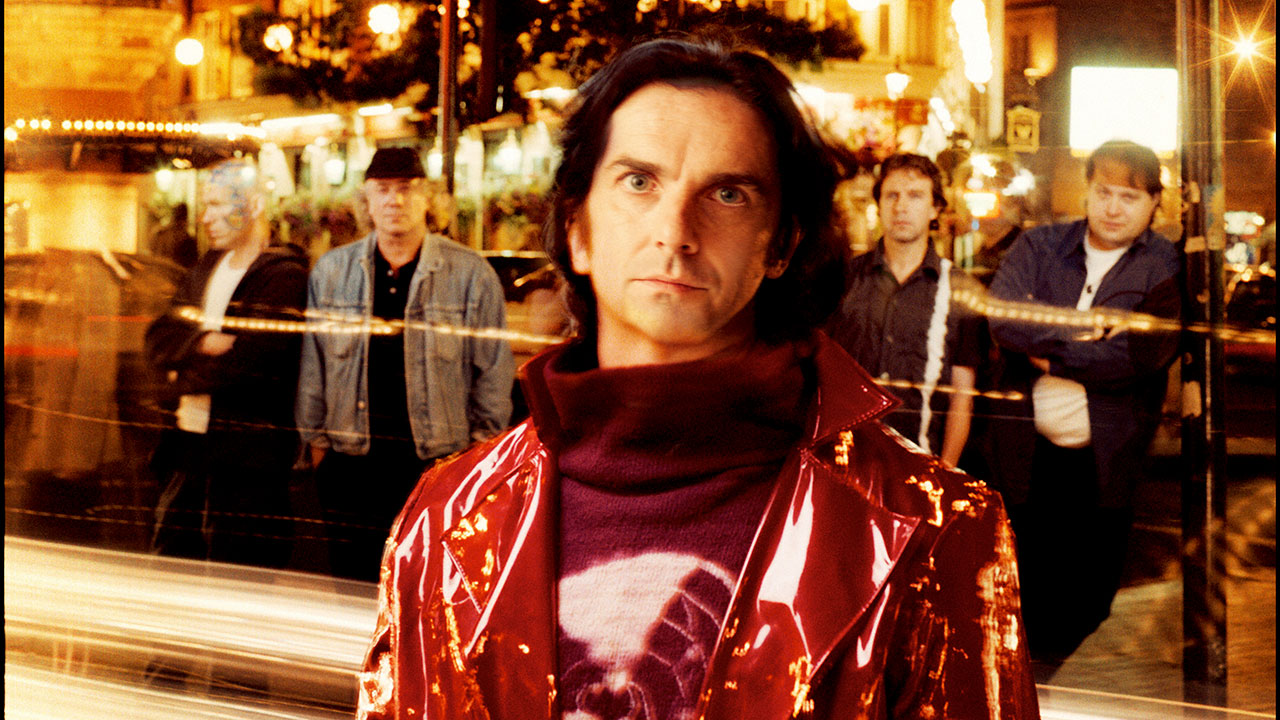

It’s January 2017 and we’re sitting in what must be the coldest room in the world, which is in a Territorial Army headquarters in south London. Downstairs, young people are hoofing and singing as a man playing an electric piano thunders through old hit songs and a tech crew hoick chunks of scaffolding about. On the front gate is a sign that says: DELIVERIES FOR BAT ROUND THE SIDE. The HQ has been commandeered by the latest rock musical to trouble the UK. Based on the original 1977 Meat Loaf album but including songs from every era of writer Jim Steinman’s career, Jim Steinman’s Bat Out Of Hell The Musical (to give it its full title) is on the surface a rock musical in the vein of We Will Rock You, Mamma Mia and that one with Rod Stewart songs that nobody can remember but it happened. And yet it’s also totally unlike any other rock musical ever written.

I arrive at the rehearsal rooms to find the cold dispelled by a great deal of activity. The cast are insanely young – I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a room round the back where chorus members are being birthed – and so full of engaging stage-school enthusiasm that they seem to be talking to each other in emojis. Amid a forest of leggings, bits of costume and modern haircuts, the show’s director, Jay Scheib, is being terrifically organised, moving actors around and correcting their mistakes

I watch a scene. Strat, played by Andrew Polec, sings a few lines from Lost Boys And Golden Girls, a Steinman song first released on his Bad For Good album, and then stalks the stage, blond and intense and slightly scary. He’s the hero of this dystopian show. I catch a few lines of dialogue. It’s good – sharp, caustic and worlds away from the lame script-filler of most rock musicals as you can imagine.

Bat Out Of Hell shares elements of its story with Queen’s We Will Rock You – a post-apocalyptic setting in the rubble of society – but where it differs is in its scope. This isn’t a jukebox musical, where the plot is constructed around a string of rock songs and you can see that from space, it’s a real show, where the songs serve the story and vice versa. The dialogue is witty, memorable and suits the characters, most of whom are full of the passionate intensity of all Steinman’s songs; the man couldn’t write a shopping list without making it sound like a message from a condemned lover.

The story is familiar, especially to lawyers. But the songs… Well, one of the problems with rock on stage is this: musicals don’t rock. No matter how much you may love Tommy as a stage show or a film, there isn’t a song in it that didn’t sound better done by The Who in a student union. Lazarus may be strange and mind-bending, but the best versions of its songs are to be found on the original Bowie albums. Not to go on, but We Will Rock You: if you think the definitive version of Bohemian Rhapsody is the one without any members of Queen on it, then you are Ben Elton and I claim my two hours back. And those are the good ones.

Bat Out Of Hell is like none of these shows for one reason only: its roots have always been in theatre (even Tommy cast itself as a rock ‘opera’). It was written as a musical, and its incarnation – its multimillion-selling incarnation – as a rock record, produced by Todd Rundgren, was only one stage in the show’s life.

“In a way,” says Sonenberg, “Bat Out Of Hell in 1977 was like a premature cast album for this musical. Steinman never gave up on his dream for it.”

It’s 1973. Jim Steinman has co-written an off‑Broadway show called More Than You Deserve. Set during the Vietnam War, More Than You Deserve attracted a great deal of critical attention, not least for the performance of Marvin Lee Aday, a young singer performing under the name Meat Loaf.

“I used to be a lawyer back in the day,” says Sonenberg, “and one of my earliest clients was Meat Loaf, Marvin Aday. He was in More Than You Deserve at the Public Theatre. At the time, [Broadway impresario] Joe Papp was interested in doing a show that Steinman had written, a futuristic Peter Pan, and Steinman had told him he didn’t need to clear any rights with the James Barrie estate. So Papp asked me if I would go see the workshop.”

Sonenberg duly went to see Steinman’s new show, Neverland. “I was blown away,” he remembers now. “It was sexy and crazy and a little violent. And there was a Peter, and a Wendy, and a Hook, and a Tink… I reported to Papp that we needed to clear rights.”

Neverland was more than just a rock version of Peter Pan, it was also a reboot of The Dream Engine, his college musical from almost 10 years before. A major reboot.

“The changes from the older version are so major, so basic and so complete that I’m going to retitle the thing,” Steinman said at the time, adding: “It really has very little relationship to Dream Engine, except for a certain ball of energy… Most of the music is new too.”

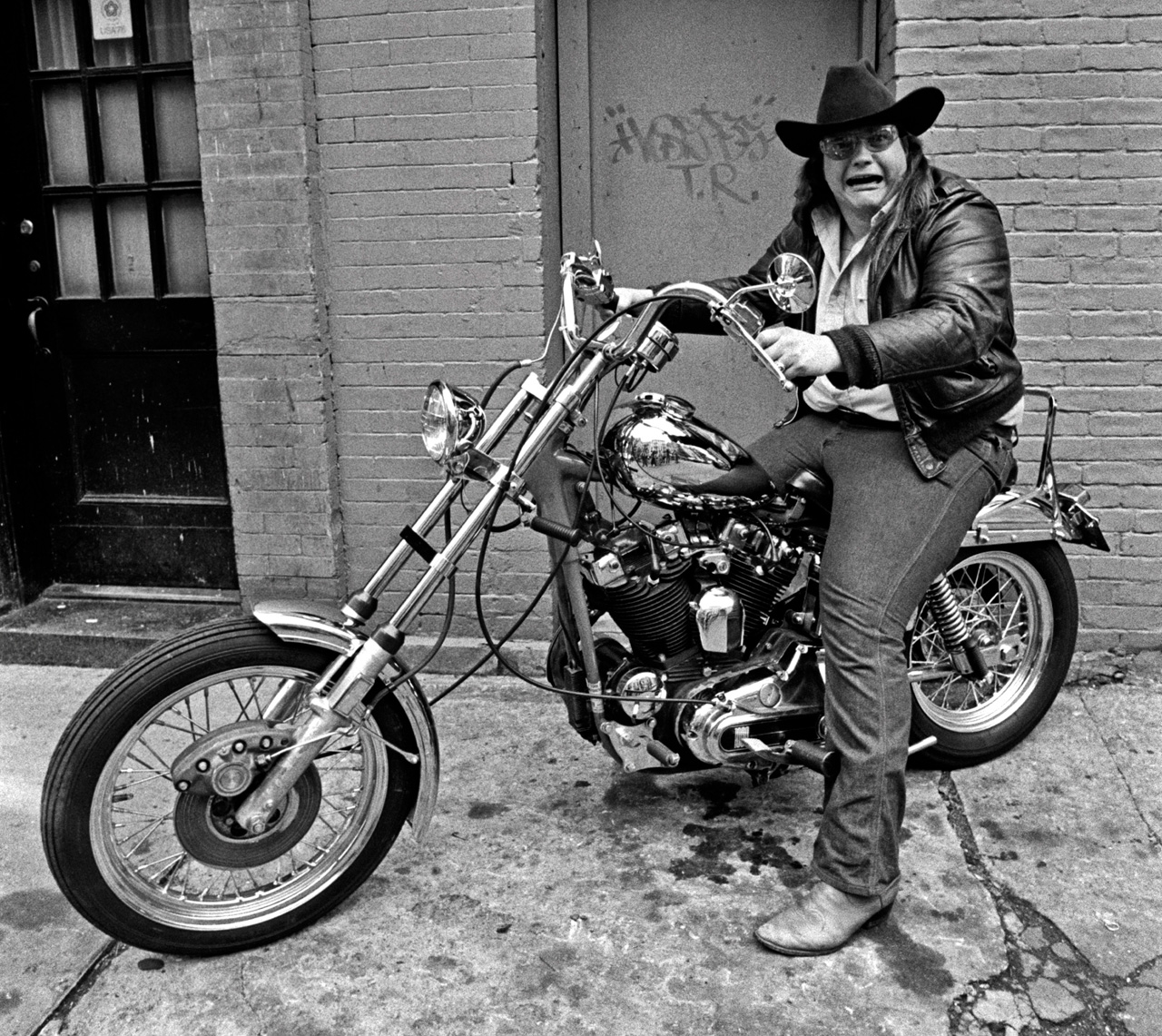

He wasn’t kidding. Replacing the often stodgy choruses of The Dream Engine was a set of songs that seemed to come from a different galaxy. They had a little in common with the music Bruce Springsteen was now making – a rockier version of classic Phil Spector seen through a poetic 1970s lens – but where Springsteen was making his music leaner and more urban, Steinman’s idea of a motorbike song made Born To Run look like an ode to a Raleigh Chopper. Steinman’s vision was operatic. There was sex, and romance; drama and melodrama; love, death and the American guitar. And even in the golden age of album rock, these new songs were long. They were also great.

“Six of the seven songs which were ultimately in Bat Out Of Hell were in Neverland,” Sonenberg remembers. “It opened up with Peter singing All Revved Up, and it was incredible.”

Neverland never happened. And there were good reasons for that. “I sent the script to Great Ormond Street Hospital, who own the rights to Peter Pan,” Sonenberg says. “And their solicitor said: ‘I’m sorry, Mister Sonenberg, you lost me at the killer nuns.’ There were killer nuns flying around, wearing habits and Victoria’s Secret lingerie…”

Neverland was dead. But the songs Jim Steinman had written for it were still great. Now he and Meat Loaf embarked on a well-documented phase of their career together. They went from record company to record company, from A&R man to A&R man, and instead of leaving a demo tape on someone’s desk they performed the whole album, in the room, just piano and vocals. (Even now, in some rest home in New York, there’s an elderly A&R man, staring into space, still traumatised from having Meat Loaf sing the entirety of Bat Out Hell right into his face.)

As a plan it was insane, and it didn’t work. It wasn’t just being in a confined space with the two most terrifying men in rock, it was also Bat Out Of Hell itself. The mid-70s was, legend has it, a time of FM rock, when West Coast bands took it easy and even the greatest British bands – Pink Floyd, the other ones – were best appreciated on headphones with some spliff. Like the A&R men, very few listeners wanted a huge, screaming maniac leaping down their ears with songs about bats and motorbikes.

“The problem with doing a record was that everybody thought this was theatrical music – it wasn’t rock’n’roll,” says Sonenberg. “They didn’t know what to make of it. First of all the songs were very long – and at that time they were even longer! And songs like Paradise, people didn’t know what to make of it. Record companies thought it was bizarre.”

Famously, Bat Out Of Hell found its first music biz supporter in Todd Rundgren. Rundgren, whose own genre-blending music showed a similar defiant attitude to categories, also had a sense of humour.

“I think Todd thought it was stupid, but he loved it,” says Sonenberg. “He thought it was amazing.”

With Rundgren’s support, and money from the tiny Bearsville label, the songs from Bat were finally recorded. But not without problems, There was, for example, the owner of Bearsville, rotund former Bob Dylan manager Albert Grossman.

“Albert said: ‘I’m not signing Meat Loaf,’” laughs Sonenberg. “I said: ‘Why?’ He said: ‘Because he’s too fat.’ And Albert was twice the size of Meat Loaf!”

Despite this, Bat was made, and made well. Amazingly well. In the wake of its ridiculous success, we take it for granted that Bat Out Of Hell is an extraordinary record. It sits in thousands of record collections next to Rumours and The Dark Side Of The Moon and, like those records, it sounds both immediately accessible and like nothing you’ve ever heard before. Most of this, of course, is down to the combination of Jim Steinman’s music and Meat Loaf’s incredible presence and singing powers (a combination much less effective when split in two, as we shall see), but Todd Rundgren’s work can’t be underestimated. From the famous revving-bike guitar on the title track – and fuck my old boots, is there a better opening song on any album than Bat Out Of Hell? – to the Spector drums on You Took The Words Right Out Of My Mouth, from the boogie melodrama of Paradise By The Dashboard Light to the gentleness of For Crying Out Loud, Todd Rundgren’s work on Bat is as sympathetic as it gets. Not that anyone thought this at the time.

“We shopped it around for about a year,” Sonenberg recalls. “It was finished, it was sounding amazing, and everybody hated it. I mean, they were literally establishing record companies for the sole purpose of passing on Bat Out Of Hell!”

Finally the album was picked up by Cleveland International (“Which was not a huge label,” Sonenberg notes drily), and it began to sell. Slowly. Very slowly. There’s an album you can buy, a recording of a radio broadcast from November 28, 1977, of a Meat Loaf show at the Bottom Line in New York. It’s the eleventh show Meat Loaf has done with his band. Bat Out Of Hell has been out for less than six weeks, and you can tell from the audience’s reaction – distracted and not initially engaged. Meat Loaf’s performance changes all that. After the band warm up with Bolero, they slam into Bat Out Of Hell – first song, please continue to fuck my old boots – and perform it exactly as they do on the album. Ten minutes of a song that’s new to most people. And Meat Loaf does not let up.

A few Steinman moments apart to let Meat get his breath back – the “wolf with the red roses” intro and a deranged version of Jim’s Love And Death And An American Guitar monologue – then Meat Loaf bites the audience in the neck and drags them into his world, where he devours them entirely.

By the end he’s shaking audibly and almost speaking in tongues – with his Texan accent he literally sounds like a revivalist preacher – thanking “Jimmy – I call him my wife,” and saying: “Mister Steinman, he don’t write easy stuff.” The band tear into a medley of Two Out Of Three and All Revved Up, and afterwards the audience are whooping and cheering. The radio announcer reports that Meat Loaf has collapsed: “We can see him. He’s definitely collapsed,” he says. “Oh my.”

This intensity is what helped to break Bat in the end. After a performance on The Old Grey Whistle Test in which Meat Loaf and co-singer Karla DeVito all but sweated themselves naked in BBC Television Centre, Britain – and then the world – finally got Bat Out Of Hell. It went on to sell more than 43 million copies, and spent nearly 500 weeks in the UK chart. Steinman’s faith in his own talent and Meat Loaf’s abilities was finally justified.

Naturally, it all went wrong after that. Scheduled to record a follow-up, Renegade Angel, Meat Loaf lost his voice. In a move that has since been criticised, Steinman decided to record the songs himself. The results – released as Bad For Good – were mixed. That is to say, songs like Rock’n’Roll Dreams Come Through and Lost Boys And Golden Girls were brilliant, but Steinman’s vocals were not. Even the then-uncredited presence of Meat Loaf backing singer Roy Dodd on some tracks didn’t help.

Meat Loaf recovered, and he and Steinman made Dead Ringer, but again, despite a strong single (the title track recorded with Cher), it wasn’t Bat Out Of Hell and sales were disappointing.

After that, Meat Loaf and Steinman parted company. Steinman wrote for his girl rock group Pandora’s Box (the original It’s All Coming Back To Me Now), Bonnie Tyler and others. Meat recorded so-so solo albums. They eventually reunited for Bat Out Of Hell II, in which Meat reworked several Steinman songs and had a massive worldwide hit with I Would Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That). A third attempt to visit the well, Bat Out Of Hell III, caused a final rift between the two men, and they haven’t worked together since.

“Meat and Jim had had an interesting and well‑travelled relationship, and then their relationship sort of dissolved,” says Sonenberg. “Unfortunately there was tension again between them. Now they’ve become really supportive of one another but neither of them are in great health.”

But they’re both still with us, and there is, finally, Bat Out Of Hell. In the wake of rock musicals like Lazarus and even films like the brilliant Sing Street, it could be that the age of the jukebox musical is finally over, and the way is open once more for shows where every song tells a story. In its new context, on stage, Bat Out Of Hell makes a lot of sense.

On stage at the Territorial Army headquarters in south London, the cast are gathered to perform an oldie but goldie. Despite the fact that even their parents might not have been born when it was first released, they do a gorgeous Dead Ringer For Love, keeping in all the bawdy sass of the original and adding new attitude of their own. It’s not Metallica, but then nor was West Side Story, and that did okay.

I have a brief chat with the show’s leads, Andrew Polec (“It’s very exciting to be doing this music as it was originally intended”) and Christina Bennington, who plays Raven (“I think people will be surprised by how much context the songs have. They were intended to be where they are now”). They’re young, and brilliantly talented, and will wow audiences.

Later I write some questions for Jim Steinman, but he doesn’t respond. I read in the papers that Meat Loaf has seen the show and was moved to tears by it. On the Tube home I play every Jim Steinman song I can find. Like every sane adult, I had reservations about this show being any good, but now I think it just might be. When you think of those songs – not just the melodies and the choruses, nor even the sheer passion, but the dramatic honesty (Paradise’s extremely sad ‘It was long ago and it was far away/But it was so much better than it is today,’ for example) – they contain more than enough for any West End stage.

“It’s been a long time in coming,” Sonenberg says as I say goodbye, “but the interesting thing is how people thought this music was too much like the theatre. And then when we tried to bring it to the theatre, people thought it was too rock’n’roll… It’s been a long time in coming. And it’s really, really right. Its real home is in the theatre.”

David Quantick is an English novelist, comedy writer and critic, who has worked as a journalist and screenwriter. A former staff writer for the music magazine NME, his writing credits have included On the Hour, Blue Jam, TV Burp and Veep; for the latter of these he won an Emmy in 2015.