A tour to the Dark Side: how Pink Floyd built their biggest album on the road

In early 1972 Pink Floyd were lacking direction. A year later they emerged from Abbey Road with an album that would overshadow everything they had done before

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

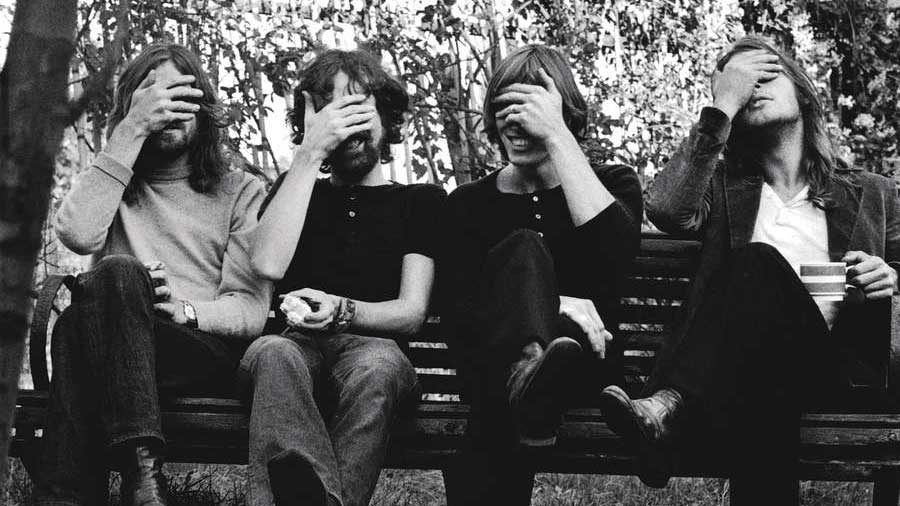

In November 1971, Pink Floyd returned from a five-week US tour and took stock before making plans for the following year. Their latest album, Meddle, had been released earlier that month.

It was dominated by the side-long epic Echoes that they had laboriously pieced together over the course of recording sessions during the first half of the year. Starting with an accidental ‘ping’ as Rick Wright set up his keyboards in the Abbey Road studio, the piece had the less-than-optimistic working title Nothing, which had gradually progressed to Son Of Nothing and then Return Of The Son Of Nothing.

Nonetheless, the band were satisfied with the final piece. And it had gone down well when they premiered it at the first Crystal Palace Garden Party, in May 71, an event they headlined over the Faces and Mountain. PA company WEM had supplied a 2,600-Watt sound system for the Hollywood Bowl-style stage, with new bass bins, parabolic reflectors and horn speakers that it was said had stunned and killed most of the fish in the lake that separated the stage from the audience.

The fish had also been harassed by a 40ft inflatable octopus that rose up during the finale of A Saucerful Of Secrets, another lengthy instrumental, amid billowing clouds of coloured smoke.

All of which served to distract from Pink Floyd’s perceived lack of personality. Which didn’t bother the faithful, who were perfectly happy to sit on the grass, roll a few and soak up the carefully constructed dynamics of Floyd’s soundscapes and whatever visual effects the band threw in for good measure.

It bothered the rock press, though, who were in thrall to the gladiatorial excesses of bands like the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, ELP, The Who, Jethro Tull and Yes as they barnstormed their way around America. In contrast, Pink Floyd’s studied anonymity, their growth by stealth out of the underground movement of the late 60s, their refusal to wave their willies around on or off stage, was almost an affront.

But the press had to be a bit circumspect. A recent Melody Maker readers’ poll had put Floyd second behind ELP in a list of favourite British bands. It would be unwise for any hip rock journo to pour too much scorn on Floyd and risk alienating their readers.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Their previous album, Atom Heart Mother, featuring another side-long epic, had reached No.1, and even though the highest chart positions were currently being monopolised by the flamboyance of Zep’s Four Symbols, ELP’s Pictures At An Exhibition, Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells A Story, John Lennon’s Imagine and T.Rex’s Electric Warrior, Meddle was clearly going to sell a lot of copies.

So the music press had to suck it up and run quotes from drummer Nick Mason stating that: “One of the worst possible beliefs is that pop stars know more about life than anyone else. The thing to do is to move people, to really turn them on, to subject them to a fantastic experience and stretch their imagination.”

He wasn’t even sure that there was definite course of progress in their music.

“People see continuations and progressions, but it’s not apparent to us. We just get an idea for something and then we try and do it.”

Pink Floyd’s big idea from their deliberations was to write a batch of songs ahead of a planned British tour in January 1972 so that they could be road tested and refined before they came to record them for the follow-up to Echoes. They were aware that while they were getting the big epic tracks right, the other side of the album was more hit-and-miss. They talked about developing a common theme that might link the songs together – something around the stresses and strains of modern life.

“At the start we only had vague ideas about madness being a theme,” Rick Wright told one interviewer. “We rehearsed a lot, just putting down ideas. And then in the next rehearsal we used them. It flowed really well. There was a strong thing in it that made it easier to do.”

“As a concept it was pretty loose,” Mason recalls. “It grew out of group discussions about the pressures of real life like travel or money. But then Roger [Waters] broadened it out into a meditation on the causes of insanity.”

The band set up in a dingy warehouse in South Bermondsey in London owned by the Rolling Stones, before relocating to a friendlier rehearsal space in West Hampstead, and spent three weeks knocking the songs into shape. They reached back to previous albums to find ideas that had been overlooked or rejected for whatever reason.

Breathe was taken from an unused idea for a soundtrack Waters had worked on with avant garde composer Ron Geesin for a film called The Body; Brain Damage was left over from Meddle; Us And Them was salvaged from recording sessions for the soundtrack to the film Zabriskie Point; On The Run grew out of a jam by Wright and David Gilmour; The Great Gig In The Sky was a Wright piano solo to which they added some pre-recorded tapes of The Lord’s Prayer and of philosopher Malcolm Muggeridge in full rant.

Money, on the other hand, was a brand new song. And according to Mason, “when Roger wrote it, it more or less came together on the first day."

Waters took charge of writing the lyrics for the songs, describing them as “more literal in concept, not as abstract as the things we’ve done before”. The band even came up with a collective title, Dark Side Of The Moon, before discovering that British blues-rock band Medicine Head had just released an album with that title. Instead they retitled the songs Eclipse, although ironically the song of that title did not emerge until later.

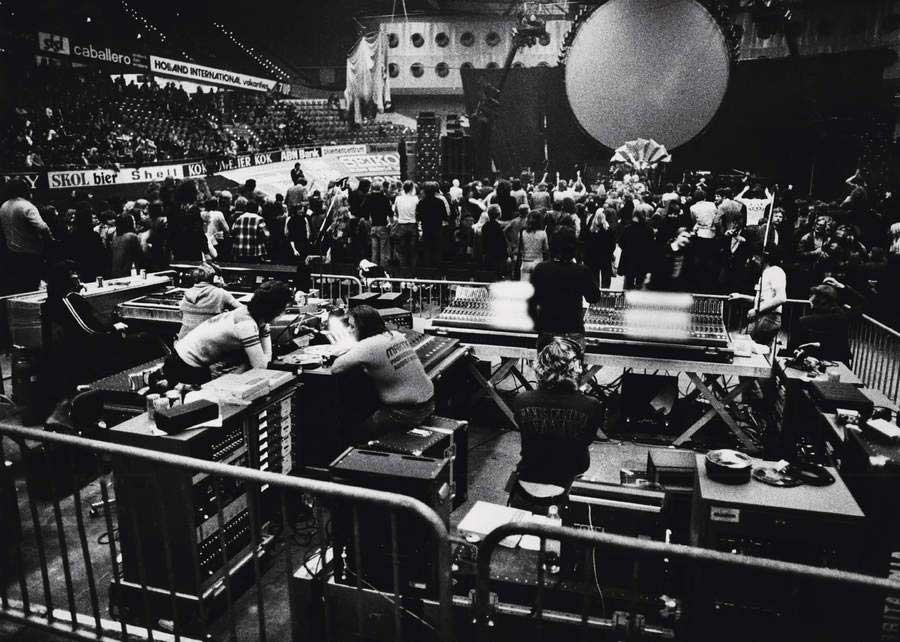

Three days before the tour was due to start, the band transferred to London’s Rainbow Theatre where they worked up a full show using the nine tons of sound and lighting equipment that they were now carrying around with them. Significantly, they had a new lighting director, Arthur Max, who they had lured over from the New York venue the Fillmore East.

Most major bands were now using lights and a little dry ice to enhance their shows. But Pink Floyd were operating in a different league. Their lighting was more innovative, and they used special effects like magnesium flares and mirror-balls to highlight the more dramatic moments, all of which required careful co-ordination.

The Eclipse suite of songs made up the first half of the show, while the second half featured Echoes, Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and One Of These Days, with Careful With That Axe, Eugene for an encore. But it was apparent from the technical glitches on the first date of the tour, in Brighton, that they hadn’t given themselves enough time to get the show up to scratch. This included setting up a row of speakers at the back of the hall and creating a quadraphonic sound system that could literally send sounds spinning round the venue.

It was taking the road crew six hours to set up all the equipment and another four hours to take it all down afterwards. A power cut after half an hour meant that the Manchester show a few days later had to be abandoned and rescheduled. It wasn’t as if Pink Floyd weren’t giving their road crew plenty of respect. Promoters booking the band were confronted by a six-page rider to the contract, starting with the specifications for the stage in order for it to carry the weight of the equipment.

The venue had to be available from 8am on the day of the show and there had to be two separate power sources for the sound and the lights to prevent any interference that could send the keyboards out of tune. The promoter also had to supply 16 ‘humpers’ to help move the equipment in and out of the venue, and a threecourse meal would be served to the crew at an agreed time – “a sit-down meal with waitress service”. Coffee, tea and soft drinks should be available throughout the day.

In contrast, the band’s own requirements were pretty modest. By the time the band returned to the Rainbow for a four-night set of shows at the end of the tour they felt emboldened to invite the press along. The Sunday Times reported: “It looks like hell. The set is dominated by three silver towers of light that hiccough eerie shades of red, green and blue across the stage. Smoke haze from flares that have erupted and died drifts everywhere. A harsh white light bleaches the faces of the musicians to bone.

“If all this sounds like The Inferno, you would be partly right. The ambition of the Floyd’s artistic intention is now vast. Yet at the heart of all the multi-media intensity they have an uncanny feeling for the melancholy of our times. In their own terms, Floyd strikingly succeed. They are dramatists supreme.”

The Financial Times weighed in with: “If anyone else attempted such a visual and aural assault it would be a disaster. The Floyd have the furthest frontiers of pop music to themselves.”

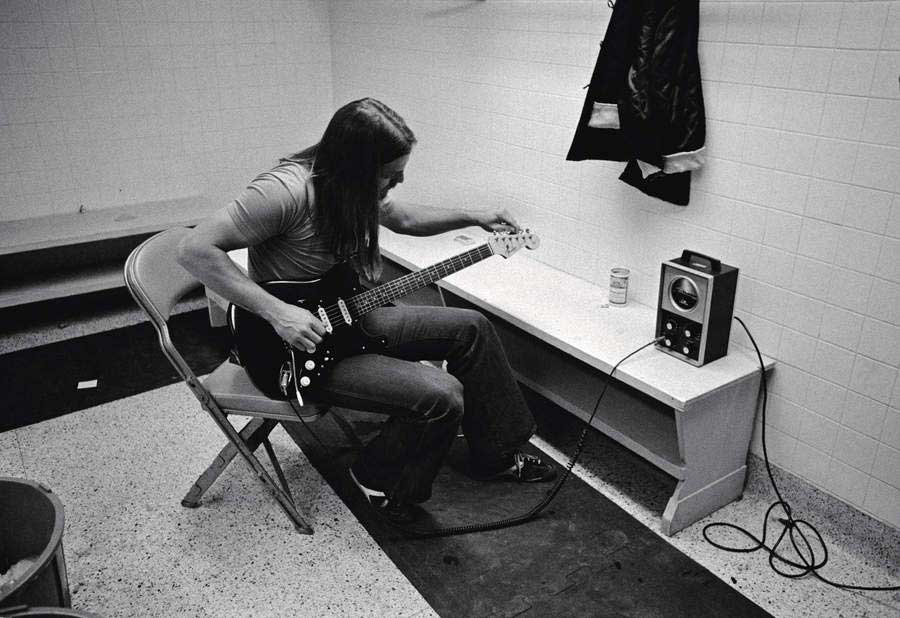

The new songs were performed roughly in the order that they would eventually appear on the new album. Breathe was largely complete. On The Run was driven along by a driving, bluesy riff from Gilmour, but while Wright supplied an approximation of the ‘whirring helicopter’ sound effect, aided and abetted by Mason’s rapid tom-tom beats, there were none of the more potent sounds that Wright would create on the EMS Synthi-A synthesiser once they got the song into the studio, this time enhanced by Mason’s heavily treated hi-hat.

Time was played considerably slower than it would eventually be on the record, and without the distinctive sound of the Rototoms (metal-rimmed drums with no shell, tuned by rotation) that Mason found lying around the studio. And The Great Gig In The Sky was a meditative piano solo from Wright with some contrasting synthesiser sounds added in the middle along with the pre-recorded voices, but none of Clare Torry’s histrionic vocals that would transform the track when she was brought into the studio to wail and howl her legendary contribution near the end of the recording sessions.

The suite of songs originally ended with Brain Damage and its allusion to Pink Floyd’s missing person: founder member Syd Barrett – ‘The lunatic is on the grass’ and the final line ‘I’ll see you on the dark side of the Moon’ which explains why they were so pissed off with Medicine Head for beating then to the album title. But Waters always felt that it needed another ending, and eventually came up with Eclipse which completed the whole thing.

In an interview around the time of the tour, Mason was asked why the band hadn’t toured Britain in more than a year, and he confessed that he felt embarrassed to be on stage still playing Set The Controls and Careful With That Axe, Eugene four years on.

“The audience are more likely to trap us in a morass of old numbers,” he said. “They are divided between getting bored with old numbers and reliving their childhood or reliving their golden era of psychedelia or even just wanting to hear what it was all about. These are okay reasons for wanting to hear something, but they’re not very valid for us. At the moment we are writing some great new stuff, so I’m happy.”

He was also convinced that performing the songs live before recording them had a lot going for it: “It’s a hell of a good way to develop a record. You get really familiar with it. You learn what you like about the pieces and what you don’t like. And it’s quite interesting for the audience to hear a piece developed. If people saw the show four times it would have been very different each time."

Rick Wright felt that playing new songs was sometimes preferable to trying to play some of their earlier songs live: “We have had difficulties,” he confessed, “for example with Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast. We tried playing it on a British tour and it didn’t work at all so we had to give it up. None of us really liked doing it anyway. It’s rather pretentious and it doesn’t really do anything. We did a similar thing at the Roundhouse that was spontaneous and worked much better – frying bacon on stage and Roger throwing potatoes about. Maybe Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast is just a weak number.”

When the tour was finished, rather than taking a break the band had a prearranged project to record a soundtrack album for a film by director Barbet Schroeder called La Vallee, aka Obscured By Clouds, and spent two weeks recording at the ‘Honky Chateau’ outside Paris. They then loaded up their gear and flew to Japan where they played a series of shows, followed by one in Australia. After that it was back to America in April for a three-week tour up the EastCoast.

The schedule included two nights at New York’s prestigious if somewhat staid Carnegie Hall, and a couple of critics took a similarly stodgy point of view, complaining that the music was being swamped by the extravagant stage effects and light show. Others went too far in the opposite direction, hailing the return of psychedelia and the spirit of 1967. Pink Floyd shrugged; they could have sold out a week at the Carnegie Hall.

By now the new songs were sounding settled, and they entered EMI’s Abbey Road Studios at the beginning of June 1972 to begin recording them. Their familiarity with the songs meant they got the basic tracks down within a month, but the overdubs and mixing would take longer as they inched their way slowly towards perfection.

They took July and August off, not having had a proper break for a year and a half, and in September were back on another US tour, this time on the West Coast, which gave them the chance to impress the chic Hollywood Bowl audience with an array of mirror-ball tricks, a battery of searchlights scouring the night sky, flames rising from cauldrons at the back of the stage, and a flaming gong.

Now that the recording process was under way there were fewer changes to the songs as they toured. Wright confirmed that “at the beginning the songs changed quite a lot, but once they’d been recorded they pretty much stayed the same”. The band were already starting to think about how to present The Dark Side Of The Moon (they had reappropriated the title after the Medicine Head album had disappeared without trace) once it became the main part of their show.

In October they were back in the studio. But they were back out on the road for some European shows the following month, and were then distracted by being invited to write some music for French choreographer Roland Petit’s ballet company. It was a typically fuzzy early-70s artistic endeavour, with the ballet being based on Marcel Proust’s novel Remembrance Of Thing Past. Then it was going to be based on Aladdin. Then A Thousand And One Nights.

Ballet superstar Rudolf Nureyev was going to dance in it, and Roman Polanski was going to film it. But it fell apart after a boozy lunch when Polanski suggested making a pornographic ballet and Nureyev nervously pulled out. In the end Petit agreed to use some existing Pink Floyd music, and Pink Floyd agreed to perform it live in Paris in January, just as they were finishing the (inevitably fraught) mixing sessions for The Dark Side Of The Moon. After that they went back to the Rainbow Theatre to prepare for another US tour, this time with The Dark Side Of The Moon as the main attraction.

The week that the album was released, Pink Floyd played New York’s illustrious Radio City Music Hall, and pulled out all the stops. One reviewer wrote: “The midnight show had a real buzz. The audience consisted of Summer Of Love survivors, new rock glitterati and Andy Warhol. The lights dimmed at 1.30am and clouds of pink steam came through the vents as Floyd emerged on a platform elevator through the floor at the rear of the stage playing Obscured By Clouds. A trio of lighting towers with a reflecting dish on the central one bathed the band in shades of red light as the elevated platform attained its full height before sliding forward towards the cheering audience – all the work of Arthur Max, the band’s lighting designer and self-proclaimed ‘fifth Floyd’.

“Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun was performed in a firestorm as yellow and orange smoke rose and strobe sparks showered off the drum kit. At the climax of the song Roger lunged into a giant gong that burst into flame.

“After the intermission the house lights dimmed as a huge, floodlit balloon moon hovered overhead and the hall reverberated to the throb of a heartbeat. At the end of On The Run an aircraft was launched from the back of the hall, crashing on to the stage in an explosion of smoke. The hall was then transformed into a panorama of clocks and watches for Time. The band added sax player Dick Parry and a female duo of backing singers to recreate the album."

Pink Floyd had given themselves a tough act to follow, and they had a couple of shows lined up at London’s Earls Court in May. The omens were not good; a David Bowie concert there earlier that month had been roundly castigated for its poor sound and cold atmosphere.

Floyd began with Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and Careful With That Axe, Eugene. One review described dry ice “tumbling down like a waterfall” during Echoes. After the interval they played The Dark Side Of The Moon. “It started with the stage littered with landing beacons and searchlights looking for an aircraft which eventually appeared and flew slowly over the audience, crashing onto the stage in a fireball. Later on they fired a salvo of rockets from the stage which flew up wires and into the audience.

"After ten minutes of wild applause at the end another half a dozen rockets signalled the return of the band who played One Of These Days as an encore. As the audience emptied into the night, searchlights positioned on the roof of Earls Court scanned the night sky.”

In June ’73 they were back in the US, this time focusing on the Midwest, which was a new market for them. But it was not a particularly happy experience. They were used to being heard in relative quiet as the audience absorbed the spectacle, but here the audiences greeted them as conquering rock heroes and came to whoop and holler. As David Gilmour put it: “We were used to all these reverent fans who’d come and you could hear a pin drop. We’d try to get really quiet, particularly at the beginning of Echoes that has these tinkling notes, trying to create a beautiful atmosphere, and these kids would just be shouting for Money. And Roger didn’t like it one bit.”

They took a break for the summer, returning for European shows in October and then playing a London show at the Rainbow Theatre in early November as a benefit for Robert Wyatt, the former Soft Machine drummer who’d been paralysed by a fall. They crammed as many of their special effects as they could into the theatre. The reviews noted the “huge balloon suspended over the audience with pictures of the moon projected on it. The concert ended with a ball of mirrors hanging over the stage reflecting thousands of needles of light into the audience and emitting coloured fog at suitable times.”

And that was the last anyone saw or heard from Pink Floyd for nearly a year. Not that they were idle in the meantime. They’d begun the near-impossible task of following up The Dark Side Of The Moon with the madcap idea of recording an album using only non-musical instruments – wine bottles, rubber bands, sellotape, whatever.

When they came to their senses, they set about writing some new songs that they could hone into shape live, just like they had before. They lined up their first British tour for two and a half years, and bought a huge circular screen to set up behind the band and made some films to project on to it while they played The Dark Side Of The Moon.

The six-week UK tour started in early November, with the first half of the shows consisting of three lengthy new songs: Shine On You Crazy Diamond, Raving And Drooling and You’ve Gotta Be Crazy. (The latter two would not make the next album, Wish You Were Here, but would surface on the one after, Animals, as Sheep and Dogs.) The entire The Dark Side Of The Moon took up the second half of the shows, with Echoes as a more than generous encore.

Promoters and hall managers noted how well-behaved the fans were. It took them awhile to cotton on to the fact that a stoned audience is generally more peaceable than a drunken crowd. What most people expected would be the last full live performance of The Dark Side Of The Moon took place at the Knebworth festival in July 1975. Pink Floyd had already played two US tours that year, and their road crew had arrived back frazzled and with scarcely a week to repair and revive the equipment before the show.

The band had arranged for two Spitfires to buzz the 100,000 or so spectators at the beginning of the show. But a communication breakdown resulted in the aircraft approaching the festival site early, as the road crew were still tinkering with the equipment and the ambitious outdoor quadraphonic sound system, and the band had to run on stage to be ready to play the opening chords of Shine On You Crazy Diamond as the noise from the Spitfires died away.

They played the rest of the Wish You Were Here album, which would be released in a couple of months, before playing the whole of The Dark Side Of The Moon, complete with films of cash registers, tumbling coins and piled-up copies of the album, along with just about every special effect they had at their disposal. They encored with Echoes.

But of course it wasn’t the last performance of Dark Side. Floyd revived the complete album for their 1994 tour, which produced the live album Pulse released the following year. Roger Waters played it on tour in 2006. And if you fancy blasting it out of your window one balmy evening this summer you’ll probably find half a dozen people outside nodding along. It doesn’t look like its ever going to go away.

David Gilmour remains adamant that playing the songs live before recording them was a vital factor in Dark Side’s success. “You couldn’t do that now, of course,” he says, “you’d be bootlegged out of existence. But when we went into the studio we all knew the material. The playing was very good, the music, the cover and the concept all came together. And it was the first time we’d had great lyrics. I thought it was a very complicated album when we made it, but when you listen to it now it’s really very simple."

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.