"He screwed up bad…" In the 70s, members of Little Feat grabbed our writer by the throat for asking about Lowell George. After his death, they were able to look back honestly

Little Feat look back on "the Orson Welles of rock", Lowell George

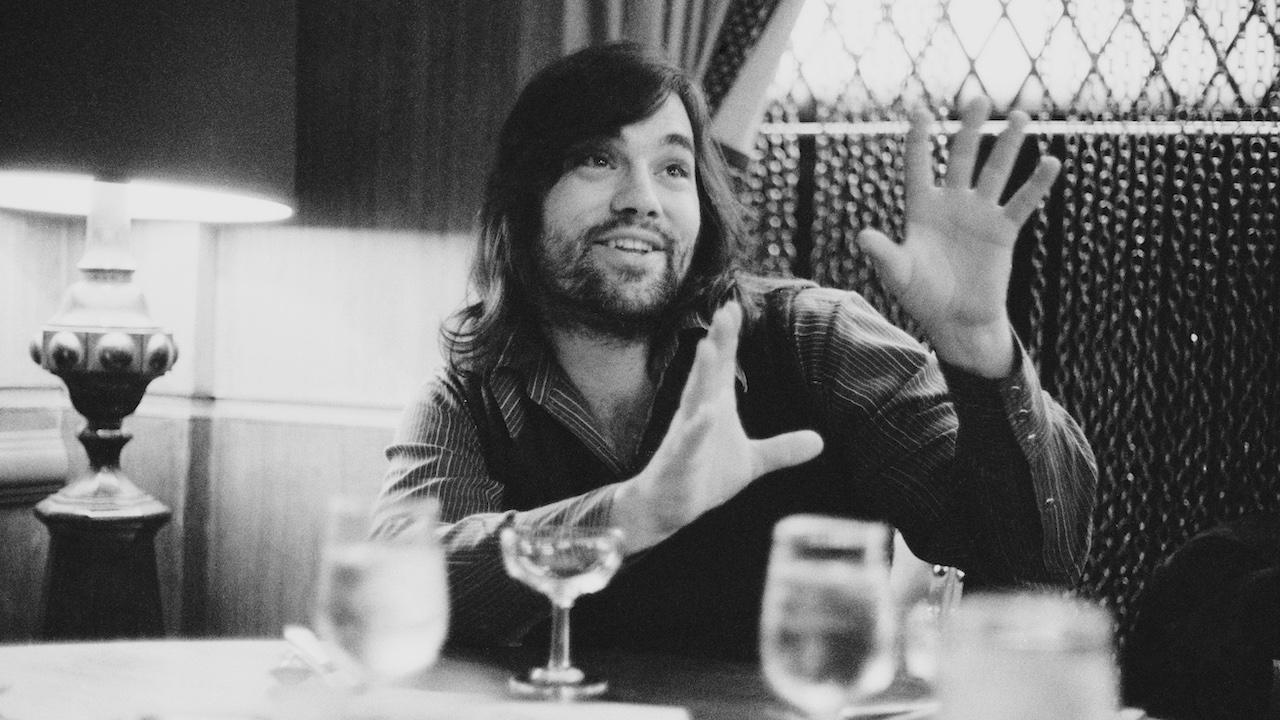

It’s June 1977 and Lowell George, the self-styled leading light in Los Angeles band Little Feat – and “the Orson Welles of rock”, according to Jackson Browne – is sitting in the Soho offices of Warner Brothers Records, ostensibly to promote his group’s sixth studio album, Time Loves A Hero.

Although the record will go Top 10 in Britain and win a gold disc, Lowell is aware that advance murmurings suggest that this is not Feat’s finest hour. It is an opinion with which he readily concurs. Featuring only one out-and-out George composition – Rocket In My Pocket – Time Loves A Hero smacks of an enforced democracy, and seems to have sidelined the bulky man slouched in front of me wearing his customary soft street urchin cap and dungarees.

If Little Feat are not quite tip-top at present, Lowell is positively under the weather. While it’s only midday he sports the air of a fellow who hasn’t been to bed at an appropriate time. On the table in front of him is a half-drunk bottle of Courvoisier brandy (a second will be summoned before the hour is out), and one of those plastic beakers which usually house a pencil sharpener. Except this receptacle is filled to the brim with cocaine – and so is Lowell.

Friendly enough, but far from lucid, he explains the state of play in between tipping out ever larger amounts of white powder and nipping at his liquid luncheon. Given that he is suffering from hepatitis and his skin is sallow yellow, Lowell isn’t looking after himself. Already weighing in at around 18 stone he moves and breathes with difficulty.

“To be truthful, I’m not even sure if I’m still in the band, which is fine if that’s what they want, except it’s still my group,” he says in a rare moment of animation. “I’ve heard they wanted to sack me, but how can they? I can sack them. I’m the one with the solo Warners deal.”

And so the conversation goes, in ever-decreasing circles. Lowell is dismissive of keyboard player Bill Payne’s central piece, the moog-laden Day At The Dog Races. “He wants us to sound like Weather Report because he’s on a Joe Zawinul trip and the others are too lazy to care. I couldn’t play on that song. I wouldn’t even do it live. Richie [Hayward, the Feats drummer since 1970] won’t say anything. So now it’s Bill’s band? I don’t think so.”

Almost eight months later I meet Hayward in the same place, and we conduct a fraught interview sitting on either side of a disused recording console in the basement. By now Little Feat are set to release their double live album Waiting For Columbus. Once again diehard followers have demurred, citing the superiority of certain bootleg discs – Electrif Lycanthrope, Rampant Syncopation, and If You Got It A Truck Brought It.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Increasingly exasperated by my line of questioning regarding George’s status, Hayward eventually snaps. A man with an infamously short fuse and a propensity for mood-swinging, Hayward leans across the desk and grabs me by the throat.

“How many more times do I have to say…” he splutters. “This ain’t just Lowell’s group and we ain’t his backing band. Yeah, we’ve sacked him and yeah, he’s come back. Happens all the time.” He releases my neck and is suddenly calm.

“Anyhow, they’ll probably sack me when I get home,” he mutters darkly. “That’s how this group operates.”

Fast forward to 2008, 30 years later, and Lowell George has been dead for most of them. He succumbed to a massive heart attack in 1979 at the Twin Bridges Marriott Hotel in Arlington, Virginia, after a final show playing material from his highly regarded solo album Thanks I’ll Eat It Here.

Little Feat, however, are still with us. In 2008, their new album, Join The Band, majors in classic Lowell songs like Sailin’ Shoes, Willin’, Dixie Chicken and the autobiographical Fat Man In The Bathtub.

Since the recordings feature guest friends as vocalists – Dave Matthews, the Black Crowes’ Chris Robinson, country smoothies Brooks and Dunn, Vince Gill and George’s daughter Inara (who he can barely have known), old ghosts have been awoken with New York Times acerbic rock critic Jon Pareles questioning the validity of the project.

Speaking from his home in Montana, keyboard player Bill Payne sounds like a man who has had time to ruminate on both sides of the story. A founding member with Hayward of the pre-Feats group The Factory (an offshoot of George’s brief stint in Frank Zappa & The Mothers Of Invention), Payne has dealt with the painful issues of what he calls “the elephant in the room”.

During their initial eight-year career, Payne and George were frequently at loggerheads. “It’s not entirely wrong to say Lowell was the leader, but then one has to lead,” says Payne. “He was fine for a while, but he didn’t have the capacity or the sense of responsibility.

"He’d do silly things like lose master tapes [George famously left some vital Allen Toussaint horn charts and mixes, destined for the album Feats Don’t Fail Me Now, on a train between New Orleans and LA] and he took too many drugs. He was like Jerry Garcia. He’d disappear for weeks at a time on some binge and then come back in reasonable shape. ‘Oh, you’re back! Great!’.

I thank Lowell for taking me on. But, man, he screwed up bad.

Bill Payne

“He was my mentor in The Factory and Little Feat, a hero to me, like our original bassist Roy Estrada, because they’d been in the Mothers. I went to LA to join the Mothers, so I thank Lowell for taking me on. But, man, he screwed up bad.”

Given George’s evident charisma (“He was a charmer, made people think they were his best friend, especially when he took them to party,” says Payne), there was a romantic notion that he was the innocent victim of a plot in which the rest of the band were cast as villainous chances.

Payne laughs. “I’ve resolved that issue. Finally. Took a long time. I used to be sensitive to that allegation. Lowell was a part of the family and I can’t discount that. I mean, I fell for him too, because he was the best of what there was, a phenomenal singer and a brilliant slide player. Sure he was good and in the beginning he was in charge, but eventually we were dragging him along.

“There was always conflict and then also a lot of camaraderie. He played a huge part, the main part, but he couldn’t manoeuvre the business on his own. We became handcuffed, like in a dysfunctional marriage.”

The first time Payne met George he’d been summoned for an informal audition to the singer’s home on Ben Lomond in Los Felix, half a mile down the road from the Charles Manson Family’s starting point in the LaBianca/Sharon Tate murders.

“I got there as requested and he wasn’t around. Big surprise. There was a beautiful blonde who let me in and said, ‘Make yourself at home, he’ll be back in four hours’. So I looked at his record collection and his books – the Smithsonian Blues album which included Join The Band [by celebrated folk act The Georgia Sea Island Singers], Muddy Waters, John Coltrane, Lenny Bruce, and tomes by Carl Sandberg, Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, [Hubert Selby Jr’s] Last Exit To Brooklyn… I knew I was going to like him even though he had a nasty-looking Samurai sword on the wall [George was a brown belt in Okinawan karate] and I was a hick from Waco, Texas.”

The last time Payne had a conversation with George he told him what he thought of him. How he’d had it and blown it, and messed the group up in the process. For once George was mortified and contrite.

“He was crying when he left, but I was justifiably mad. Everything was in limbo. We’d let him come back to produce the live album and what became the posthumous Down On The Farm, but he still wasn’t in full control. I respected him for letting me say my piece – saying that I loved him, but I hated him as a human being and for his inability to keep it together. He was so bad at handling pressure, and he wouldn’t delegate unless it was clandestinely done, to others outside the band. He was just too fucked up. That’s why he died on tour.

“The last time I saw him was a bit later. He came to my house on his motorcycle and he opened his mouth and he was so gone he couldn’t speak a word. He was standing in my front yard with tears in his eyes. It was very painful.

"I thanked him for what he’d taught me and said, ‘Look when you come back from your solo tour, try and relax and produce us properly’. I know he’d enjoyed producing the Grateful Dead’s album Shakedown Street so I told him to be honest for once and get Little Feat back together – but do it properly. For himself. I didn’t want to be the leader, I wanted the best for him.

"And that was it. He got back on his bike and left. I was extremely angry. He dropped the ball and I knew he was asking for help, like Richie often was. Me? I was tired of it all.”

When he heard that George had died after playing a gig at the Lisner Auditorium, Washington – the Feats’ most fervent fan base, where much of the Waiting For Columbus set was captured – the post-mortem showing signs of a drug overdose, coupled with liver degeneration, Payne was furious.

“I wasn’t surprised. He didn’t set his affairs in order, there was no finance for his wife and children. We did a benefit concert at the Forum in Los Angeles and raised $250,000. It was the only practical way to deal with his death.”

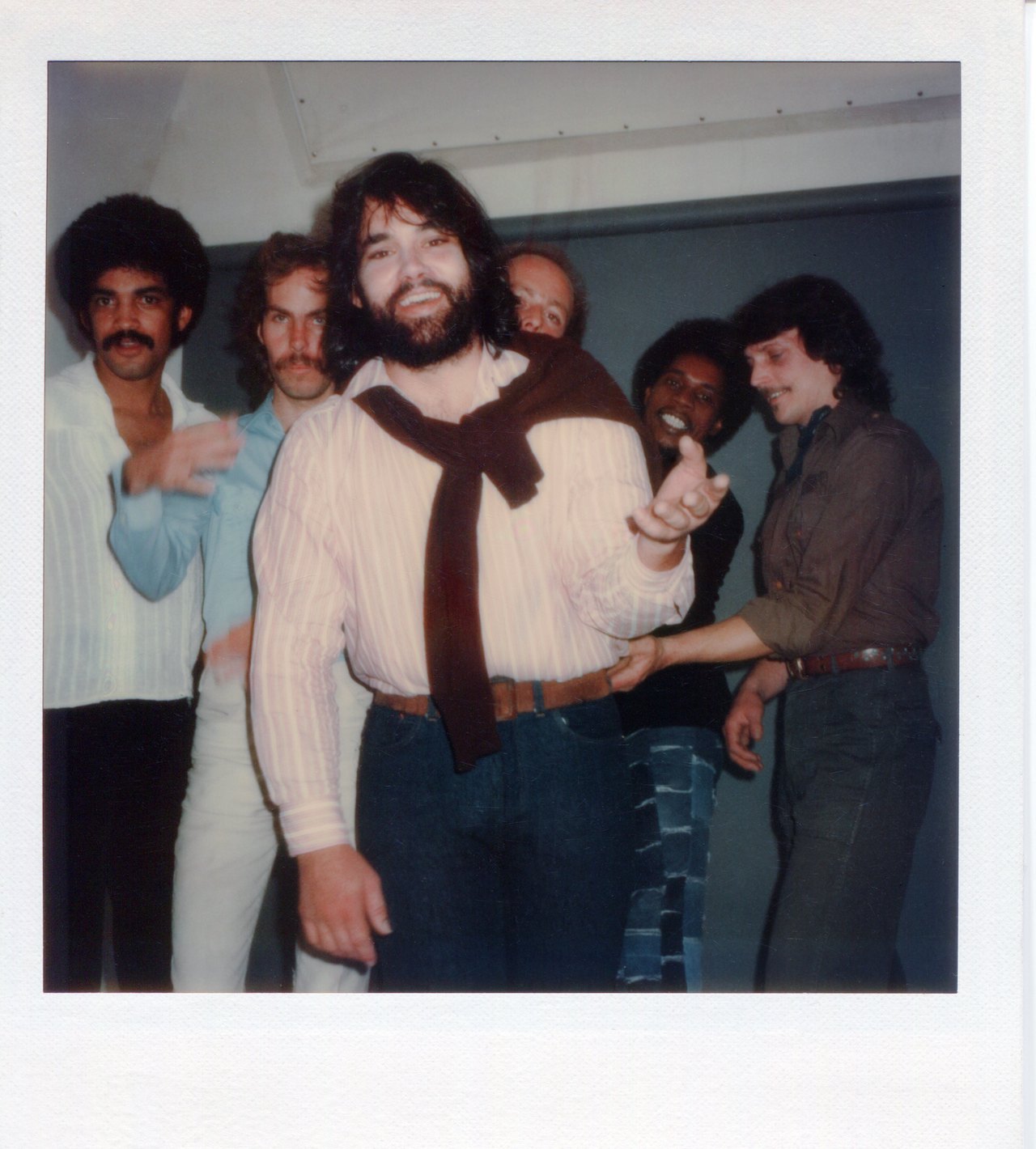

Little Feat guitarist Paul Barrere joined the group in 1972 before their classic third album, Dixie Chicken, with fellow newcomers, Louisiana musicians Kenny Gradney and Sam Clayton. This was the line-up that came to British attention in 1975 during the Warner Brothers Music Show, a package involving the Doobie Brothers, Tower Of Power, Montrose and Graham Central Station. Little Feat’s incendiary rock funk blew all else out the water and they became overnight heroes in Europe, fêted by Eric Clapton, Led Zeppelin, mutual hedonist Robert Palmer, and the Rolling Stones (whose Keith Richards told them, “You’re a part of the family”).

Barrere died in 2019 but back in 2008 , he remembered that period well. “We were a freight train comin' atcha – kickin’ ass. We were always opening slots and blowing people off. That tour got sticky because of our reaction. Thing was… Little Feat weren’t showmen – we didn’t have a catalogue of hits. We just played. We had a jazz combo sensibility à la Miles Davis, plus a black R&B thing, down to Kenny’s bass and Sam’s percussion.

"Lowell was phenomenal – he made his slide, which he played with an old spark plug, conjure up Hawaiian melodies or pedal steel. It was so eclectic that we could be out of our skulls and still function. It was nirvana on stage, and it was funny. We were tongue-in-cheek with our stage props. We didn’t think: 'This is serious art'.”

They didn’t, but maybe Lowell – who called his songs “cracked mosaics” – did. Son of a wealthy Hollywood furrier, George was steeped in classical LA tradition. He attended Hollywood High and grew up in a house on Mulholland Drive. His family owned a ranch outside Las Vegas, later sold to Howard Hughes. Because of his daddy’s business, the George home was filled with the cream of Californian society, movie stars, crooners, and mink-wearing glamour girls.

Lowell’s oldest school friend and sometime collaborator Martin Kibbee also grew up next to megastars like WC Fields, Sandra Dee and Bobby Darin. He maintains that Lowell’s upbringing instilled a starry adventure from an early age. “He was born under a bad sign – the Hollywood sign,” says Kibbee, pointing out that Little Feat misspelt their name to echo The Beatles. He and Lowell published their songs as George/Martin, for Fab-related reasons.

The day after his birthday, on the eve of his final tour and two months before his death, George gave his local paper the Topanga Messenger a rare interview. Asked about the group’s latest split he replied, “I don’t know what’s happening. I’m not really worried about it. Groups break up and get back together again all the time. It’s no big deal. Nothing is permanent. Even in the music business.”

Pushed on his recent alleged reclusive nature he replied that was “cosmic bullshit” but admitted he had lost his competitive edge. Asked about his values he suddenly bridled. “You don’t want to hear that. My values speak for themselves. To try and keep a sense of humour amongst a lot of bullshit is really nice to do, and just recently I’ve been able to capture that. Nothing is really that important.”

Little Feat have left a substantial footprint on West Coast rock – with and without the charismatic and troubled George. Their first four albums have attained classic status, while Lowell’s solo Thanks I’ll Eat It Here is a brilliant solo disc, albeit abetted by some of the team players.

Often criticised for daring to carry on after his death – what else were they supposed to do? – Little Feat struggled initially to fill Lowell’s role, utilising singers like Craig Fuller who were on a hiding to nothing. But in their defence they’ve regrouped and kept going, building a career that has lasted longer than their original golden period, always playing George’s material and paying homage – rather than lip service – to the man who set the Feats in motion.

When Lowell George died, his ashes were thrown into the Pacific Ocean by his wife Elizabeth. The fat man in the bathtub would have seen the blackly comic side of that.

Little Feat still tour. Visit their official website for details.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.