The kaleidoscopic story of Acid, the drug that inspired music's wildest experiments

The creators and advocates of LSD were an integral influence on the genre of psychedelia, but its history is bound up in espionage and government spooks as much as fun-lovin’ hippies

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

"When the blues ran up against psychedelics, rock and roll really took off,” declared Ken Kesey. The author of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest and conductor on the original Magic Bus should know; he ensured the West Coast acid rock movement took off, having provided the fuel for the musicians to make the trip – LSD.

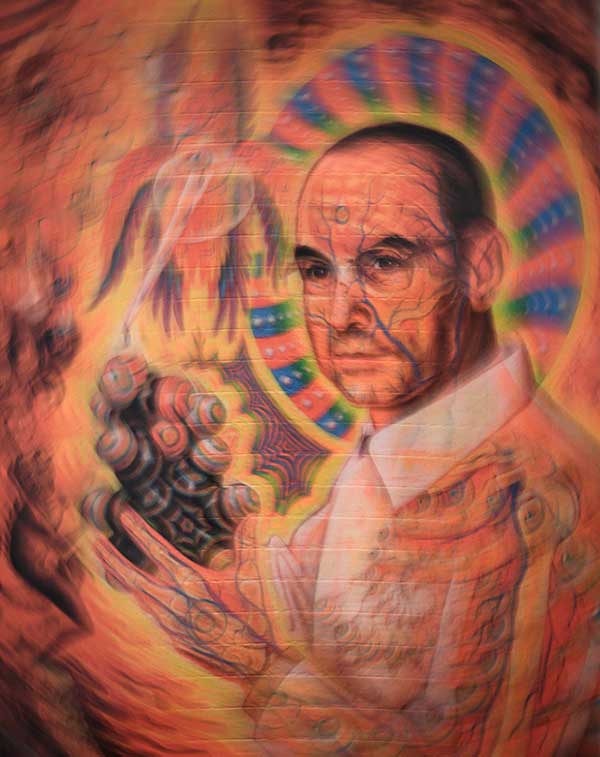

Lysergic acid diethylamide was first synthesized in 1938 by Swiss chemist Dr Albert Hofmann. He was researching the properties of the ergot fungus for medicinal purposes and thought it might be useful as a heart stimulant, but tests on animals produced nothing apart from making them ‘restless’.

Five years later he returned to working on LSD, on a hunch that there was something there. While recrystallising a batch of LSD-25 one day he started feeling dizzy and went home, where he became exceedingly restless before lying down on his bed and experiencing ‘an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense kaleidoscopic play of colours’.

After he’d come down he decided that the LSD had to be responsible and that he had probably ingested it through his finger tips. Three days later, on April 19 – a date still celebrated by acid freaks every year as Bicycle Day – he decided to test his theory by dissolving what he thought was a microscopic amount of LSD into water and promptly suffered the world’s first bad trip.

He had trouble speaking coherently and asked a colleague to accompany him home on his bicycle, which was a wise idea as Hofmann had the sensation that the bicycle was motionless and the landscape was moving around him. Once home he felt threatened by his furniture as well as a neighbour whom he asked for a glass of milk. Eventually the fear and paranoia subsided and the good trip returned. Next morning his breakfast apparently tasted delicious and his senses remained heightened although he felt a bit tired.

Having established the hallucinogenic qualities of LSD, Hofmann worked on its possible psychiatric uses. He also investigated psycho-active plants and was the first to synthesise the active ingredient in magic mushrooms as well as developing a drug to treat post-natal haemorrhaging – which some might argue was of greater benefit to humanity. He became a passionate environmentalist and died in 2008 at the grand old age of 102.

When the first research into LSD was published in 1947, the US Central Intelligence Agency soon got interested. They’d been searching for a truth drug and, having tried and failed with alcohol, caffeine, barbiturates, marijuana and mescaline, they figured LSD could be the answer. They began covert experiments, dosing a dozen soldiers ‘of not too high mentality’, and when one of them, who’d been specifically ordered not to reveal a secret, not only spilled the beans but had no recollection of doing so afterwards they became quite excited. But their elation was short-lived.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Some soldiers babbled incoherently, others couldn’t remember the secret. Predicting the response to LSD was almost impossible. The CIA remained obsessed with the mind control implications of LSD, however, and set up the infamous MK-ULTRA program. They started by testing LSD on their own trainees and ‘selected individuals’ within the organisation. Then somebody wanted to know how much LSD it would take to dose the population of Los Angeles via the water supply.

They were relieved to find out that the chlorine in the tap water negated the impact of acid. But their own scientists took that as a challenge and soon came up with a chlorine-resistant batch of LSD. They tested animals too, beginning with spiders, whose webs became even more intricate, and cats, who cowered in front of mice, and working their way up to an elephant that keeled over in a stupor and then died (this was blamed on a miscalculation of the dosage required).

The idea of being able to de-programme a Russian spy using LSD continued to fascinate CIA chiefs and an eminent psychiatrist (Dr Ewen Cameron) who’d been using LSD on schizophrenics was commissioned to see what he could do. He subjected 53 of his patients to sleep therapy, knocking them out for months at a time, followed by ‘depatterning’, using electro-shock therapy and LSD to wipe out their behaviour patterns, and finally reconditioning them by sedating them and playing tape-recorded messages up to 250,000 times under their pillows.

Unfortunately he forgot to ask their permission first and nine of the human guinea-pigs subsequently sued the US government. Like the Nazi concentration camp doctors, the CIA picked on helpless victims to test the effects of hallucinogens – prisoners, drug addicts and the like – by giving them LSD for up to an unbelievable 75 consecutive days, in increasing doses, to overcome any tolerance to the drug. They didn’t neglect their own staff’s welfare, however.

Aware that there was a difference between taking LSD knowingly and unknowingly they approached the problem systematically. Everyone in the CIA’s technical department tried LSD, in groups or in pairs, and took notes. Then they were encouraged to spike each other and the results were compared. Then they started spiking other CIA personnel who’d never before taken acid.

The operation was in danger of getting out of control and an internal memo in December 1954 firmly ruled out spiking the punch bowls at the office Christmas party. In fact, the operation had already got out of control. The previous year an army scientist (Dr Frank Olson) who specialised in biological warfare had been innocently spiked during a CIA/army training course and had fallen into a psychotic depression, eventually jumping through the 10th floor window of a hotel.

An elaborate cover-up was instigated which lasted for 20 years and the CIA’s chief scientist (Dr Sidney Gottlieb) was chastised in a memo for exercising ‘poor judgement’. Another project involving a San Francisco whorehouse where clients were spiked and then observed via two-way mirrors (the CIA paid the prostitutes $100 a night) was derailed when the guy in charge (George Hunter White), who was an alcoholic, started inviting his old buddies from the Narcotics Bureau over to party.

Outside the paranoid confines of the US security apparatus, however, LSD was getting a more favourable reaction, especially when it was applied to creative minds. Actors Jack Nicholson, James Coburn and Cary Grant, writers William Burroughs and Aldous Huxley and conductor Andre Previn were among those who sampled it in the 50s and news soon seeped into the jazz community, where the use of mind-altering drugs was endemic.

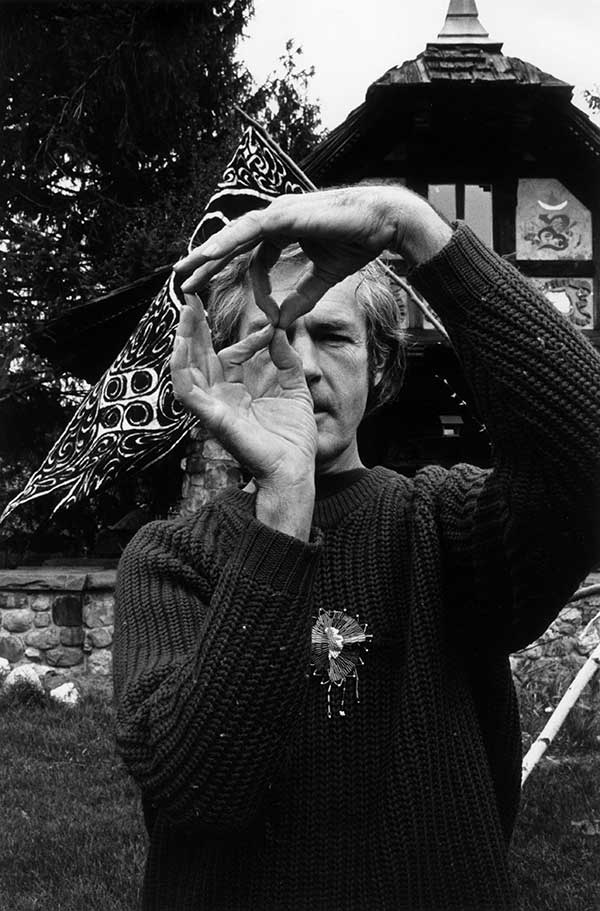

In 1961 Harvard doctor Timothy Leary was introduced to LSD by British-born psychologist Michael Hollingshead (a man so mysterious he doesn’t appear to have a date of birth) who apparently brought it over from Britain in a jar of mayonnaise.

Leary was already well-known academically for his book, The Interpersonal Diagnosis Of Personality (and not quite so well known for being expelled from the University of Alabama for spending the night in the girls’ dorm), and he set up a research project into hallucinogenic experiences, obtaining LSD from Hofmann’s Sandoz Laboratory by using Harvard stationery.

But what started as an academic project soon turned into an evangelical crusade to ‘turn on, tune in and drop out’ as he fed the drug to beat poets like Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac, who helped to spread the word. Leary also formed the League Of Spiritual Discovery to advocate the benefits of LSD. At this point LSD was still legal but the CIA, who had by now realised that acid was not the answer to their world-domination dreams, had advised the government that the drug was far too potent to be generally available to the populace.

In 1963 strict controls and restrictions were introduced by the US Congress. Harvard University also realised what Leary was up to in their name and dismissed him for taking acid with students. Undeterred, Leary set up the Castalia Institute in Millbrook, New York, to continue his crusade, but it marked the beginning of a campaign of harassment by the authorities, who managed to turn Leary from an acid spokesman to a cause célèbre, notably when they contrived to give him a 10-year jail sentence for possession of one joint in 1966.

Richard Nixon had already called him “the most dangerous man in America” and he spent some time in solitary confinement in Folsom Prison, one cell away from Charles Manson – who was arguably a much better candidate for Nixon’s label.

Leary himself did little to enhance his martyrdom. Having escaped from prison in 1970 he fled to Switzerland, only to be lured to Afghanistan, rearrested and brought back in chains. Facing a lifetime behind bars, Leary cut a deal with the authorities and grassed up everyone who’d helped him escape. Released from prison in 1976, Leary took his show on the road as a stand-up philosopher, debating with convicted Watergate burglar (and former Richard Nixon employee) Gordon Liddy.

He died in 1996, aged 76, of prostate cancer, outliving his daughter who died by suicide in prison after shooting her husband; his son, who had publicly denounced him as a traitorous dog; and some of his five wives. His last words were: “Why? Why not? Beautiful.” The following year, a portion of his ashes were taken on their final trip and launched into space.

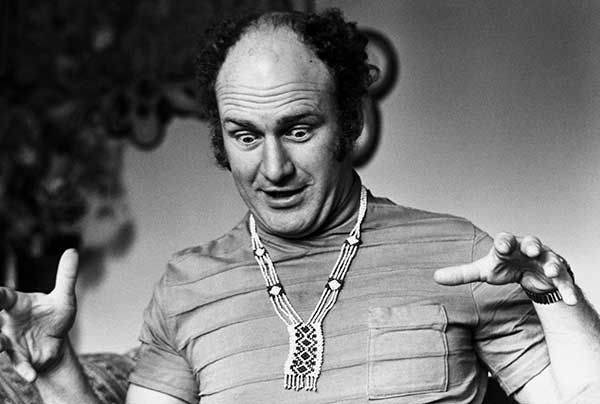

If Leary was the (self-appointed) LSD guru then Ken Kesey was the Pied Piper. And he owed it all to the CIA, taking part in their MK-ULTRA programme at Menlo Park Veterans Hospital near Stanford University, California, where he was a graduate in creative writing in 1959.

At the CIA’s expense and encouragement he sampled a whole range of hallucinogenics including LSD, mescaline and psilocybin and wrote reports about them. But he kept one particular hallucination – about an Indian sweeping the floor of the hospital ward – back for a novel he was writing.

One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, published in 1962, was set in a mental hospital, although it suggested that the really dangerous mental cases were those in positions of authority. On the proceeds of the book, Kesey moved his wife and family up to La Honda in the Santa Cruz mountains near San Francisco and set up an artists’ commune. They named themselves the Merry Pranksters and threw a series of parties called Acid Tests at which revellers would take LSD, sometimes without knowing, and then spend the night freaking out amid the Day-Glo painted trees and weird atmospheric music coming from hidden speakers.

The San Francisco bohemian subculture of writers, poets, theatre troupes and jazz, blues and country musicians became avid party goers, although the presence of local Hells Angels – introduced by writer Hunter S Thompson – could sometimes give the trippy atmosphere a bit of a jolt. The parties were easy to find; a nearby road sign had been amended to read ‘No Left Turn Unstoned’.

Having turned on California, in 1964 Kesey bought an old school bus that was daubed in psychedelic swirls with the roof adapted to form a stage and the Pranksters set off across America, stoned and tripping all the way in their colourful clothes, shouting “you’re either on the bus or off the bus” and blasting out The Beatles, Rasaan Roland Kirk and Bob Dylan from speakers on the roof, stopping to throw an Acid Test whenever they felt like it and offering spiked Kool-Aid orange juice to all and sundry. For a full account of the trip you should read Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Just about every hippie cliché you can think of was invented by Kesey and the Merry Pranksters during that trip. When they eventually reached New York they were greeted by Allen Ginsberg, who took them to Timothy Leary’s Castalia Foundation in Millbrook. They arrived unannounced in a cacophony of noise, throwing green smoke bombs from the bus. Leary came out and sat on the bus for a few minutes before retiring to his room. It appeared that Leary and Kesey had nothing to say to each other, not on this astral plane anyway.

The next day the Marry Pranksters headed back West. But Leary and Kesey did have one thing in common: harassment. In 1965 Kesey was busted for possession of marijuana. In an acid-inspired move he faked his own suicide and fled to Mexico. The cops were waiting for him when he sneaked back eight months later, although he only had to serve five months inside – which was mild considering what Leary was faced with.

When he got out, Kesey moved back to the family farm in Oregon and stowed the bus in a barn. But the Acid Test party people and the Pranksters’ house band, The Warlocks (by then renamed The Grateful Dead) had already set up their own scene in San Francisco.

Kesey kept a modest profile for the next 30 years before reviving the Pranksters for a musical play. He made occasional appearances and even came over to Britain with the Magic Bus to see the solar eclipse in 2000.

Shortly before he died in 2001 from complications following an operation for liver cancer, aged 66, he wrote an article in Rolling Stone magazine urging peace in the wake of 9/11. But the CIA was having an acid flashback in the cuckoo’s nest and hallucinating over weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. The hippie dream was long gone.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.