The decadent tale of Gary Holton: singer, actor and rock'n'roll dreamer

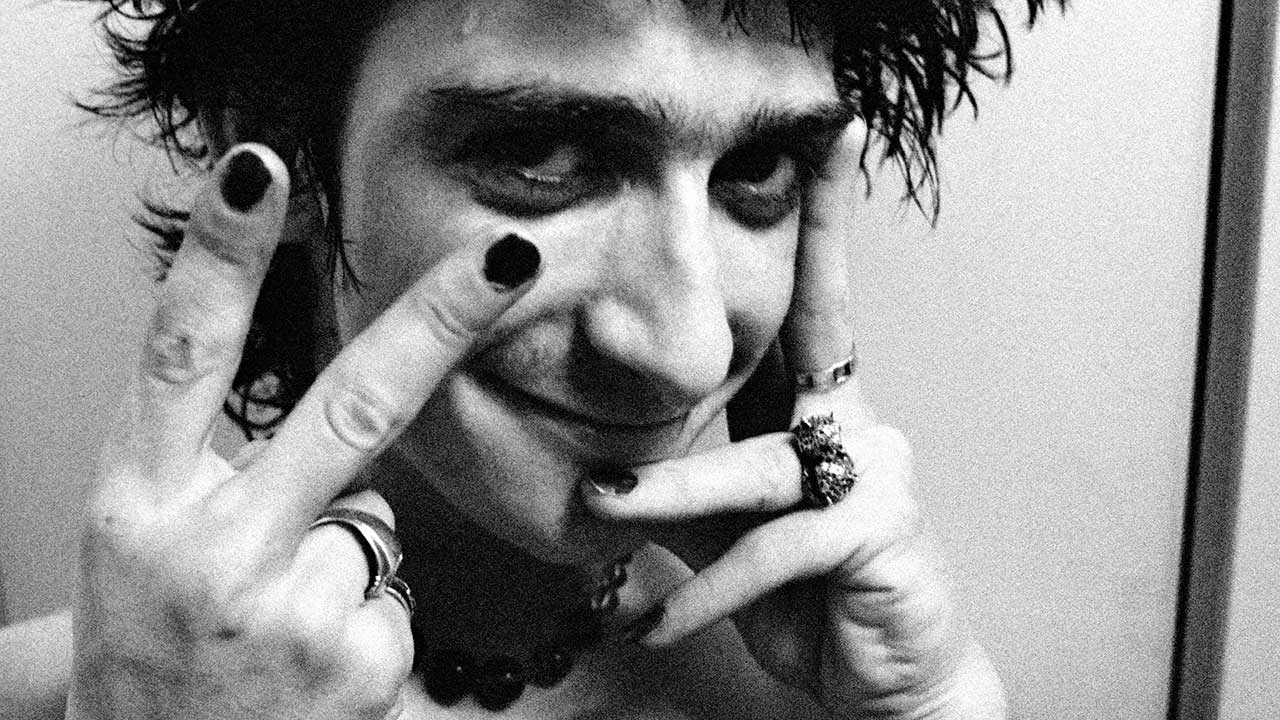

Beneath Heavy Metal Kids singer Gary Holton’s brazen, dodgy-geezer exterior lurked a fragile, ambivalent character whose idealistic dreams of rock’n’roll stardom tragically went unfulfilled

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It’s extremely likely that many readers of Classic Rock will be more familiar with Gary Holton the actor than with Gary Holton the vulgar vocalist with 70s slam-bang barrow boys The Heavy Metal Kids – the band with gutter as well as glitter, spunk as well as sparkle.

After The Heavy Metal Kids split in 1977, shortly after the release of their third album Kitsch, Holton tried to prolong his rock career via a series of doomed solo ventures – including a forgotten band called The Gems, something called Casino Steel, and a blink-and-you-missed-it stint in The Damned.

Later, in 1984, Holton had a minor singles chart hit with a croaky carouse through Perry Como’s Catch A Falling Star (produced by Jim Lea of Slade, fact fans) before deciding to quit the music business and pursue an acting career.

After a series of unexceptional walk-on, walk-off roles, Holton amazingly managed to land the high-profile part of an East End wide-boy called Wayne Winston Norris in the TV series Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, the comedy drama about British brickies on the piss abroad.

The show was a huge hit, and Holton finally found the fame he had craved for so long. But, tragically, he only made one and a half series before he died suddenly of a drugs overdose (in October 1985). His death threw Auf Wiedersehen, Pet scriptwriters Ian La Frenais and Dick Clement into confusion, as all the outdoor scenes for the second series had already been shot.

In the end they decided to prolong the Wayne character and a suitably emaciated, prickly blue-black-haired, bomber-jacketed body double was employed to sometimes scuttle across the background of the remaining series-two studio scenes, somewhere beyond the broad Geordie shoulders of Oz, played by Jimmy Nail.

It was desperately sad to see Holton, who had spent his life on the fringes of rock’n’roll success, reduced to the role of a bit-part player again, even in death. But I always used to have a wry smile on my face whenever I saw Holton in full flow playing the part of Wayne. Because he wasn’t really acting, he was just being himself.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Wayne was Gary Holton, and Gary Holton was Wayne – a supposedly streetwise, tough-talking jack-the-lad, but secretly an edgy and forlorn figure who would rather pick his nose than your pocket; who would more likely nick himself shaving than nick a motor. In modern-day television terms, you’d have to say that although Holton had the brash manner to strut and bluster like EastEnders’ Phil Mitchell, in reality he had more in common more with Phil’s loser relative Billy.

If Holton were to give to you a slap, it would have been just that – a gentle tap, resulting a slight reddening of the cheek.

An example: I remember meeting up with Holton one time just before the Heavy Metal Kids were due to undertake a huge European tour, I think as support to Alice Cooper.

The Kids’ label at the time, Atlantic Records, had just bought them a brand new, specially customised tour bus, and Holton couldn’t wait to show it to me. The vehicle was a real mean machine: a cross between a Hummer H2 and a Chrysler Grand Voyager: six wheels; big off-road-style tyres; tacky chrome brightwork; gleaming black body panels; inky tinted windows.

“It’s great, innit?” Holton declared, bursting with pride as he showed me around the vehicle. “There is one slight problem, however,” he admitted shyly. “The people who was customising the bus for us ran out of time. They didn’t quite manage to complete the job and our tour starts tomorrow. So we said don’t worry about it, deliver the vehicle to us anyway.”

Looking rather sheepish, Holton flung open a vast sliding side door to reveal the compartment the Heavy Metal Kids would be travelling in. I peered inside to discover that there weren’t actually any carpets or seats. “As I said, it’s only a slight problem…”

The following is taken from two interviews with Gary Holton that I conducted for weekly music paper Sounds in September 1975 and January ’76. Hopefully they’ll provide you with a decent enough insight into the Heavy Metal Kids frontman, who I always thought of as a charmingly arrogant little urchin; a ducking-and-weaving Del Boy kind of sleazer-geezer; an Artless Dodger with an ’eart of gold.

Some used to say that Holton’s swaggering cockney image was bogus and cleverly rendered but, having met him on several occasions, I really don’t think so. As I think I said in some Heavy Metal Kids album sleeve notes one time, with Holton it was less a case of lock up your daughters, more lock up your lock-up.

And the Del Boy comparisons don’t stop there. While researching this story I discovered a bizarre fact: in between leaving the Heavy Metal Kids and joining the cast of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, Holton made a film called Bloody Kids along with an actress called Gwyneth Strong – who played Rodney Trotter’s wife, Cassandra, in Only Fools And Horses. How spooky is that?

Anyway, when I met up with Holton in autumn ’75, one of the first things I wanted to do was clear up some confusion. (And now sounds like a curious discussion, considering how the term ‘heavy metal’ is so commonplace, and so much a part of the music industry’s fabric these days.)

“Is there confusion?” Holton asked me at the time. “Are you confused?”

He smiled a toothy smile, as if the object of the exercise really was to perplex me. “Well, that’s okay, then. I think it’s a good thing to ’ave people wondering.”

Wondering about what, you may ask.

“You want to know if the band’s still called The Heavy Metal Kids or whether we’ve changed our name to just The Kids,” Holton continued. “Right? Well, I’ll tell you what happened. When we went over to tour America, we found out that there was this thing over there that if a band played badly they’d be called heavy metal; everybody’d say: ‘Aww, that was a real heavy metal set’, meaning that it was a load of shit. So we fought that we’d better drop the front part of our name for the States. But we didn’t change it permanently or anything, y’know.

“Anyway, when we come back to Britain we find that Atlantic’s sent out these press releases proclaiming big name changes for the band and all that. It was a bit of a cock-up in some ways, but in other ways it was good, because it kept us in the press.

“I like the name The Kids, because it’s more us on stage. But we’re a loud, heavy band, there’s no denying it, you know what I mean? I will not deny it, it works both ways.”

Way back then, I made the point that, despite the name, The Heavy Metal Kids do not and never really have played heavy metal music. Boisterous bovver boys, yes; vituperative proto-punk delinquents, for sure. But heavy metal, er, maniacs? Definitely not. More confusion?

“That’s because the definition of heavy metal came after the name,” Holton claimed. Displaying some surprising literary knowledge, he added: “You see, we got the name from William Burroughs, donkeys years ago. In his writing, The Heavy Metal Kids were in fact a bunch that used to run around with truncheons tied to their waists. So anyway, we had the name for years, then all of a sudden up pops this new brand of music called heavy metal. It’s so silly. I mean, I can remember saying that I used to be in a beat group, do you remember that?”

I put it to Holton that he must have first thought about forming a band called The Heavy Metal Kids some years ago. “Yeah,” he leaned back and preened his hair with his hands, trying to restore a steadily failing quiff. “I’ve had this idea of hooliganism on stage in my brain for about four years now. The actual band has only existed for about two years though.”

The Heavy Metal Kids’ biography cited an outfit called Biggles as Holton’s first major band. However, when questioned about his early rock’n’roll days the singer’s usual colourful stream of words narrowed to a trickle.

“Biggles. Disaster. A very expensive disaster,” he laughed coarsely. “A fortune was spent on that band, it really was.”

It transpired that Biggles were in direct competition with another band, called Heaven, and – or so I gathered at the time – Holton was somehow vocalist for both of them. Not surprisingly the two groups flopped rather badly. But even today I seem to recall Biggles being promoted quite strongly in the British music press.

“I dunno. I dunno much about promotion,” Holton said, successfully manoeuvring past the subject. “The music business is a funny business. I mean, you journalists are a funny lot, too. I’ve had a lot of hostile people in interviews. I don’t know why. You’re not hostile, are you?”

Holton first took to the stage when he was 11: “I did opera for about two years, believe it or not, just small parts in Sadler’s Wells productions. Then I decided that I wanted to act, so I did a course at the National Theatre for three years. In the end I got thrown out of the course – for reasons I won’t go into – and over a period of time I got chucked out of almost every other school possible. Then I saw this ad in one of the music papers, saying: ‘Rock singer wanted…’.”

Jumping forward to that discourse in winter ’76, and The Heavy Metal Kids had just completed their Cheap And Nasty tour of Britain – a tour that “was very good for us,” Holton asserted. “The audiences are beginning to latch on to some of our songs – why, in some places they’ve even got a little chant going: ‘We want The Kids!’ they yell. That’s real emotional. I pissed in my jockstrap the other night.”

On stage?

“No, I wouldn’t do that. Off stage. I had to exercise a bit of control there."

What else happened on the tour?

"Oh yeah, we got banned from just about every hall we played in. Our act’s a bit lewd, and I think the management of some of the venues was rather shocked. I was sticking knives into the stage during one gig, and afterwards a guy come up to me and said: ‘I wish you hadn’t splintered it all up like that, we’ve got a ballet on tomorrow!’

“For the next British tour we’re going, well, theatrical,” Holton revealed. “Stage props, everything. I’ve got a five-foot tall egg being made, and we’ve got a feast of new songs. I’ve written one about falling in love with a policewoman.”

A true story?

“Slightly exaggerated, actually. It was a traffic warden to start off with. There’s one who’s always on the beat where I live, and I changed her into a police woman. She’s lovely. She writes really nice tickets – excellent handwriting.

Going back to the earlier interview for a moment, it’s worth noting Holton’s blatant proclamation that: “I’m already a star, it’s just that a few million people don’t know it yet. I know that I’m a star,” he giggled, almost childishly. “I’m working bloody hard at it. It’s all them other people, you know. But I’ll talk them round to it. One day.”

Holton also professed to being a perfectionist – which could possibly have been a product of his theatrical background.

“When I go on stage, it’s my fucking stage, you know. It’s mine,” he insisted fiercely. “That’s why if something goes wrong I tend to get aggressive. When we played the Reading Festival [in August 1975], for instance, John Peel said somefing just as I was rapping, so I lobbed a full Coke tin at him and it splashed all over his record decks. He was well pleased, I can tell you.”

Later, in the second conversation I had with him, I asked Holton how his plans for stardom were progressing. “It’s all right,” he confessed, “things are going well. It’s very demanding. But yes, I’d deeply love to be a debauched and decadent rock star. A touch of the old peeling the grapes for me, milk baths… Lovely.

“Unfortunately,” Holton concluded, adopting a hangdog expression, his quiff drooping in sympathy, “I haven’t even got any hot water at home at the moment. My boiler’s broken.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 60, in October 2003.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.