“I was in an airport and these people went: ‘Hey Steve! Thumbs up, man! Tony Soprano loves Journey!’ It was amazing”: This multi-million selling rock singer disappeared from music for more than 20 years. It took a personal tragedy to bring him back

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Steve Perry is the man who helped transform Journey from noodling jazz concern into AOR superstars – only to step away from music in the 1990s. But in 2018 he made a surprise return with a solo album, Traces, his first new record in nearly 25 years. In an in-depth interview with Classic Rock, he revealed the decision behind his retirement – and the tragedy that inspired his comeback.

Some words he sang in 1981 have echoed down the years: ‘Don’t stop believin’, hold on to that feeling…’ And yet in the life of Steve Perry there was a long period, the best part of 20 years, when his belief in music, and the feeling he put into it, seemed lost forever.

For the man whose richly expressive, high-arcing voice helped Journey to become one of the biggest rock groups in America in the 80s, the now 69-year-old’s solo album, Traces, is a surprise comeback. It ends a self-imposed exile from the music business that began soon after Trial By Fire, his final album with Journey, released in 1996 – the year in which Oasis and the Spice Girls ruled the British charts, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill was the biggest-selling album in America, Bill Clinton was in the White House and John Major was at Number 10.

As Perry says now: “I had lost that deep passion in my heart for the inner joy of songwriting and singing. I sort of let it all go. If it came back, great; if it didn’t, so be it, because I’d already lived the dream of dreams.”

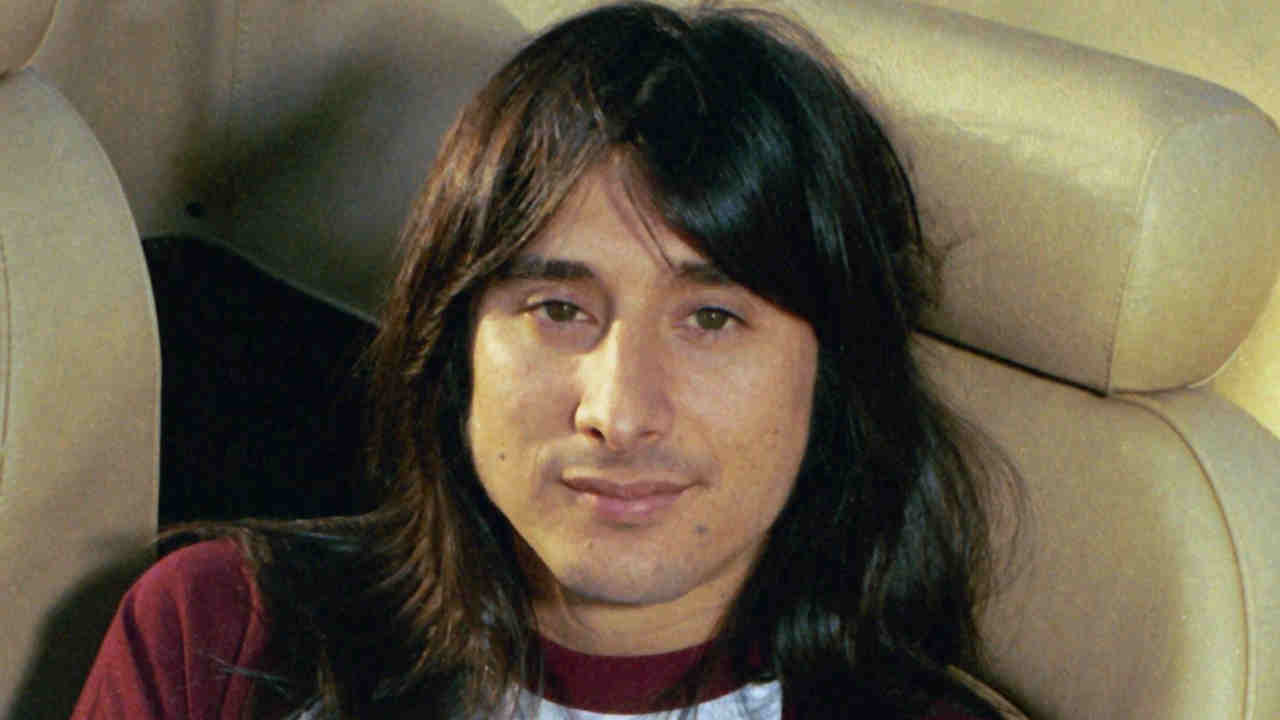

His long absence from public life has made Perry something of an enigma; the guy who had it all and walked away, the legendary singer who fell silent. In all the time that Perry remained a recluse – as he puts it: “living my life in quietness, in privacy” – Journey carried on, bringing in Perry sound-alike singers Steve Augeri, Jeff Scott Soto and latterly Arnel Pineda, a Filipino discovered via YouTube performing in a Journey tribute band in Manila.

Journey’s profile rose again when Don’t Stop Believin’, a Top 10 US hit in 1981 and a classic rock radio staple ever since, became more popular than ever, a global anthem, after it was featured in the cult film Monster, the acclaimed TV series The Sopranos and the hit teen show Glee. Perry, meanwhile, made only fleeting appearances in public – singing along to Don’t Stop Believin’ at baseball games, joining alternative rock group Eels on stage to run through old Journey hits and, more surprisingly, the Eels’ bluntly named It’s A Motherfucker.

Before his comeback, Perry had felt he was done with his career in music. He also felt he had done enough. The classic albums he made with Journey and as a solo artist – from Infinity to Escape, Frontiers, Street Talk and Raised On Radio – had sold millions. The songs he sang had helped define a golden age of melodic rock. His return to music, so late in life, is not driven by a need for money or validation. It’s the result of something far more meaningful.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

“It came out of falling in love with somebody and then losing her a year and a half later,” Perry says. “Her name was Kellie Nash. She had stage-four cancer when I met her, and we had made some promises to each other, one of which was that I would not go back to into isolation if something happened to her.”

After a moment’s hesitation, he says simply: “I kept that promise.”

It’s a late summer evening when Classic Rock catches up with Perry, at home near San Francisco. His high, singsong voice is unmistakable, his manner friendly and engaging. There is also a remarkable degree of candour in what he reveals about certain chapters in his life – his exit from Journey in the late 80s; his search for peace of mind away from the bright lights of rock stardom; most revealingly, his brief, intense relationship with Kellie Nash. In these moments he seems wide open, extraordinarily so for a man who retreated from fame and from the public gaze for such long a time.

The passion for music came back. Singing again, I was getting goose bumps. It touches me.

Steve Perry

It is when addressing other subjects – specifically his past drug use and the possibility of him rejoining Journey – that his voice hardens a little and his answers turn more defensive or oblique, or rises as he parries a question with an offhand joke.

From one such exchange comes a blunt disclosure. Asked why he rarely gave interviews to the press at the height of his fame in the 80s, he replies: “You really want to know? Will you print what I say right now?” He laughs long and hard. “Because I don’t trust journalists! I’ve had good experiences, and some not so good. I’m missing fingers, still, from the lion’s mouth.”

He says he hated being misquoted in the press. More than that, what really hurt were the bad reviews the band received. For many critics, Journey’s everyman rock was always a soft target. “I only read three reviews in my whole life,” he says. “Then I decided I wasn’t going to read them any more. Every night, we’d get one encore, a second encore. That was my review. I didn’t need to read tomorrow’s paper.”

So what’s changed? Perry says he has. “The passion for music came back. Singing again, I was getting goose bumps. It touches me. Nothing is bigger than that for me. So that’s why I’m talking to you now. Because I never thought I’d never feel like this again.”

When Perry thinks back to his childhood, he says wistfully: “Music is what I lived for as a kid.”

Born on January 22, 1949 in Hanford, California, to Portuguese parents, he is an only child. It was at the age of 12 that he first dreamed of becoming a singer, after hearing soul legend Sam Cooke’s hit song Cupid. As a teenager, Perry, like so many of his generation, fell under the spell of The Beatles. In tribute, his new album includes a version of I Need You, one of the first songs George Harrison wrote for the group.

We really struck a chord with Escape. I think there’s a lot of luck involved. We were just in the right place at the right time.

Steve Perry

In his early twenties, Perry fronted a number of California rock bands, one of which, Pieces, featured an established star in bassist Tim Bogert, who had been in Vanilla Fudge and Beck, Bogert & Appice. It was with Perry’s subsequent band, Alien Project, that he recorded a demo tape that caught the ear of Columbia Records executive Don Ellis. The band broke up in the summer of 1977 after bassist Richard Michaels was killed in a road accident. Soon afterwards, Ellis called Perry, first offering his sympathies, then a new opportunity – an audition with Journey.

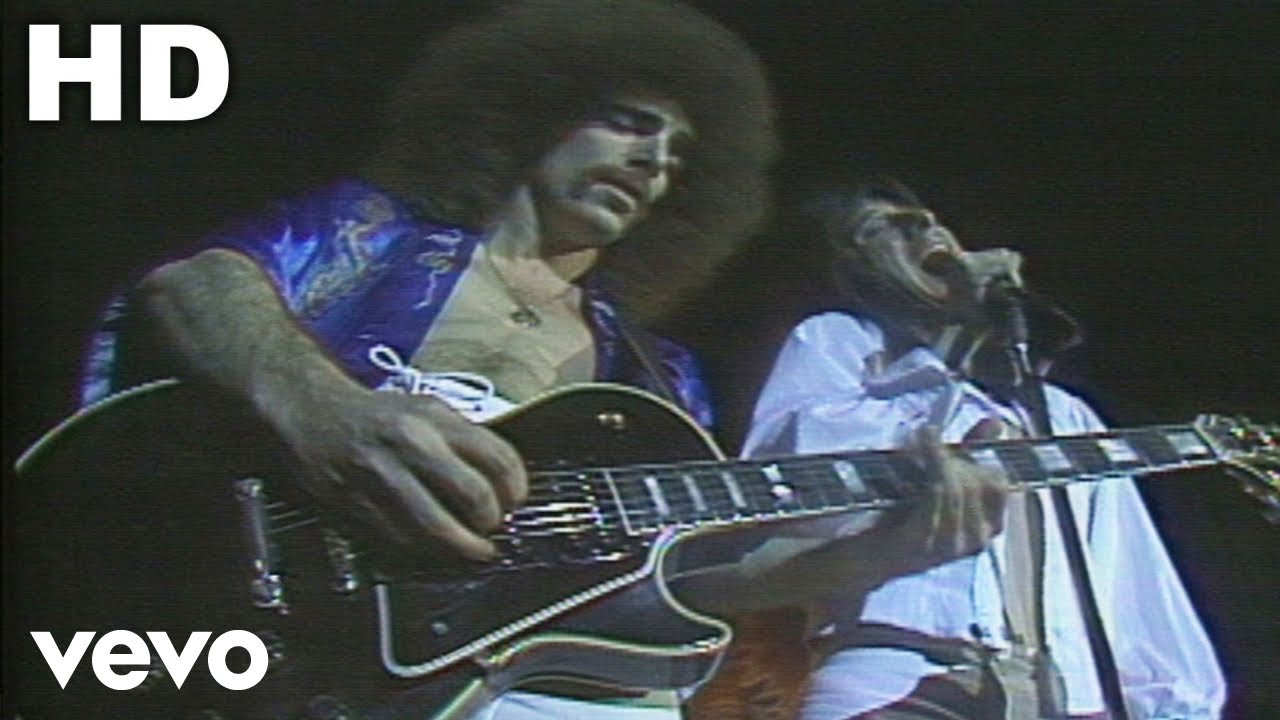

He’d seen Journey play live at LA club The Starwood. The group had been created as a vehicle for guitar virtuoso Neal Schon, a former member of Santana, and Perry liked what he heard: jazz-rock fusion, serious chops. But the first three Journey albums had bombed, and bringing in singer Robert Fleischman to share vocals with keyboard player Gregg Rolie, also ex-Santana, was not working out. Behind Fleischman’s back, Perry met with the band after a show in Denver, Colorado. Later that night, in Schon’s hotel room, he and Perry wrote their first song together, a power ballad named Patiently. And with that, Perry was in.

The first album he recorded with Journey, 1978’s Infinity, became the band’s first US Top-30 record, and more hits followed. But it was their 1981 album Escape, three albums later, that made them superstars. With Rolie having been replaced by Jonathan Cain, the band’s AOR sound was honed to perfection. Three Top 10 singles – Don’t Stop Believin’, Who’s Crying Now and Open Arms – helped power the album to No.1.

“We really struck a chord with Escape,” Perry says now. “But when you reach a sort of peak moment where everything clicks, I don’t think it’s calculable. I think there’s a lot of luck involved. I think that, creatively, we were just in the right place at the right time.”

After another multimillion seller, Frontiers, Perry also had a hit with his debut solo album Street Talk and the single Oh Sherrie. And it was at this point that the power dynamic within the group shifted. Journey had always been Neal Schon’s band, but it was Perry who took control of the 1986 album Raised On Radio, on which the singer’s soul influences dominated and the guitarist’s role was diminished. It was also during the making of this album that Perry’s mother died, which led him to re-evaluate his own life. In late 1986, when the Raised On Radio tour ended, he did not tell the band he was quitting. But as Jonathan Cain said: “I knew it was over. It was a sad, sad night.”

Perry says now that he was burned out from 10 years of touring and recording. “The pace was fast, and we never stopped.” He also concedes that he partied too hard in those days. “It was the eighties!” he says, laughing. “Everybody was pretty much having a good time, put it that way.”

The laughter doesn’t last. When he’s asked for a little more detail, he gets rattled. Reminded of what he said on a recent US TV chat show, describing his state of mind in the 80s as “toasty” and “crispy” – words evocative of cocaine use – he says sharply: “Partying comes with all sorts of toasty behaviours. And that’s about all I’ll say about that.” But then just a moment later: “I never participated in toasty behaviours before a gig or during a gig,” he insists. “But after a gig, I’ll probably see you tomorrow after sound-check…”

Having left Journey behind, what followed, as he freely admits, was a struggle to adapt to a life without the band and all that went with it.

I don’t trust journalists! I’ve had good experiences, and some not so good. I’m missing fingers, still, from the lion’s mouth.

Steve Perry

“As much I missed the lights, as much as I missed the stage, the applause and the adoration of people who were loving the music I was participating in, I had to walk away from it to be okay emotionally on my own without it,” he says. “And that took time. That doesn’t mean I didn’t miss it, it means I had to keep walking the other way. There was some personal work to be done within myself, to be honest with you.”

After Perry left Journey, Schon and Cain formed the supergroup Bad English with singer John Waite, who had previously worked alongside Cain in pop rock act The Babys. Perry eventually made a second solo album, 1994’s For The Love Of Strange Medicine. His reunion with Journey in 1996 was derailed by the cancellation of a major tour after Perry sustained a hip injury. The band waited two years before deciding to move on without him. And Perry quietly slipped away into a new life.

In the way that Perry describes his years away from the music business there is a sense of him drifting, and enjoying his freedom. He travelled the world, in a way he was never able to do as the star of a high-profile rock band. He had also made and saved enough money never to have to work again. Moreover, he explains, “I live small. I can only drive one car at a time.”

But he had not shut himself off from the outside world. “I was out of the limelight, but it wasn’t like I wasn’t tracking the reality of life.” And although he had left Journey behind, he was instrumental in the resurrection of Don’t Stop Believin’ – granting permission for the song to be used in Monster, a low-budget 2003 film starring Charlize Theron, and in the final episode of The Sopranos in 2007.

The latter, for Perry, was a tough call. He loved The Sopranos, and was thrilled to hear that the show’s creator David Chase wanted to use Don’t Stop Believin’ in that episode’s closing scene. What troubled Perry was the prospect of his song – a song so full of love and hope – playing as the lead character, mafia boss Tony Soprano, got bumped off. It was only after Perry was told, in strict confidence, how the scene would play out that he gave Chase his consent. To Perry’s delight, the scene had Tony Soprano putting quarters into a jukebox and picking Don’t Stop Believin’ over songs by Heart and Tony Bennett.

On the day after that final episode was shown on TV, Perry discovered that he was cooler than he had ever been before. “I was in an airport,” he recalls, “and these people went: ‘Hey Steve! Thumbs up, man! Tony Soprano loves Journey!’ It was amazing.”

I had to walk away from it to be okay emotionally on my own without it. That doesn’t mean I didn’t miss it.

Steve Perry

But it was his involvement in Monster, and the friendship he formed with the film’s director, Patty Jenkins, that would change the course of Perry’s life.

In 2013, after many years, Perry was working on music again. “I wasn’t sure how it was going to go,” he says. “It had been so long since I opened up my soul to that. But I allowed myself to do it with the idea that if I didn’t like what happened I would delete it and no one would ever hear it.”

Then, through Jenkins, and purely by chance, he met Kellie Nash. For Perry this is a deeply personal story, but he says he’s comfortable discussing it in the public domain. “I totally am,” he says emphatically. “I will tell you how it came about, if you want me to tell you.” The inference in his voice is clear: this has profound meaning for him.

“It started when I was watching Patty editing a TV show about cancer,” he begins. “Patty told me: ‘I put real people who have cancer on the set with my actors.’ And as the camera panned across all these people, I said: ‘Who’s that?’ She said: ‘It’s Kellie Nash, a friend of mine. She’s a PhD psychologist.’ I said: ‘Maybe I need a new shrink!’ Patty asked me why I wanted to know about Kellie. I said: ‘There’s something about her that’s talking to me.’ I asked Patty if she would email Kellie and say that her friend Steve would love to take her for a coffee. She said: ‘Okay. But before I send the email, there’s something I need to tell you. She has breast cancer. It’s in her bones and lungs and she’s fighting for her life…’”

He takes a deep breath. “At that moment I didn’t know what to do. I’d lost my mother and my dad and my grandparents. I don’t think I was ready to get to know somebody just to lose them. My heart said send the email, my head said I don’t know. So I listened to my heart.

“After two weeks of me going crazy, Patty says it’s okay for me to email Kellie. I’ll never forget it. You’d think I was writing the best lyric of my life. I wanted every word to be what I felt. After some emails between us, we talked on the phone for five hours one night. A few nights later we went to dinner at six o’clock and we closed that restaurant down at midnight. After that we were inseparable.

“I remember telling her, about three or four dates later, that I was crazy about her and I loved her. She said: ‘I love you too.’ That’s when the conversations got really deep. We talked about her cancer, and she said: ‘This is some nasty stuff. I don’t think you want any of this.’ I said: ‘I don’t care.’ I told her: ‘It’s like two tracks on a rail. That’s what going on over there, and we’ll get through that together. But you and I are over here.’

“One night, when we were falling asleep, she said: ‘If something was to happen to me, promise me that you won’t go back to isolation and make this all for nought.’ I didn’t know how to navigate such a statement. She was looking at the arc of her whole life, and us getting together, loving each other. The possibility of us not being together, I just didn’t want to talk about it…”

His voice shakes and trails off before he says quietly: “I made the promise. And then I lost her, twelfth of December, 2014.”

For the third time in his life, Perry’s career had been shaped by the loss of someone close to him. The death of Richard Michaels had led to Perry joining Journey. The death of his mother had contributed to his exit from the band.

I had a couple of years of serious crying and every now and again I still get mugged by it.

Steve Perry

He says he still grieves for Nash. “I had a couple of years of serious crying,” he sighs, “and every now and again I still get mugged by it. It happened again just yesterday. But there was something she said to me: ‘This cancer might take my life, but it can never take our love for each other’. And I have found that to be absolutely true.”

Nash was the inspiration for Perry’s new album Traces, but he does not think of this as simply a memorial. “Some of the songs are about Kellie,” he says. “Some are sad, but there are happy songs too – songs that rock, they’re joyful, they’re hopeful. And that emotion, finding my passion again for music, is certainly about her.”

In the context of Perry’s career, Traces has a style and tone more reminiscent of his first solo record, Street Talk, than of his work with Journey. There’s a modern AOR feel in the album’s beautifully crafted opener No Erasin’, and in the upbeat rock number Sun Shines Gray, and in a series of smooth ballads there are the soul and R&B influences that informed Street Talk. And while his voice has changed with age, now operating at a lower register, the essential qualities – the nuanced phrasing and the emotional depth – remain.

“Nobody is the same as they were thirty years ago,” he says. “But I do tell you this: I am as emotionally as committed with what I’m trying to say with my voice now as I was then, if not more.”

In the way that Perry sings now, there is a similarity to Robert Plant. And just as Plant declined to be involved in a full-scale Led Zeppelin reunion in recent years, so Perry has consigned his former band to his past. Neal Schon has said the door is open for Perry to rejoin Journey, but Perry won’t be walking through it.

“I think the band is doing really well,” he says. “Arnel is a great singer. And I’m enjoying what I’m doing. I love my new music, even if I’m sad that it took what it took – that my heart had to be broken to be complete. And after I swore I’d never do this again, I really believe in what I’m doing with this new record. Isn’t it better for the soul to keep reaching for the things that you’re afraid to do, not the things that are safe to do? Isn’t it better to keep pushing into the future so that you feel like you’re living your life on the edge as it unfolds? I think that Robert Plant is doing that, and it seems to me he’s loving it. Why go back? Throwing yourself into the abyss of the unknown, and trying to figure that out, is thrilling to me.”

Perry’s says his comeback, so long in coming, and so unexpected, might not end with this one album. “I’ve had conversations about potential live shows,” he reveals. “And I’ve got a shitload more songs sitting around. I would love to do another record.”

What is most surprising in all of this is that Perry has no regrets about all the time he’s been away: no sense that he might have, maybe should have, made more of his talent.

“That was one of the things I pondered at one time,” he says. “But I have no problem with it, which is really amazing to me. I think the word ‘if’ is really a waste of time. As long as you’re doing the very best you can, in the moment, I don’t think it’s right to look back and think about ‘if’. Instead of looking at anything as a regret, I’d rather move forward. Right now that means more to me than anything.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 255 (October 2018)

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.