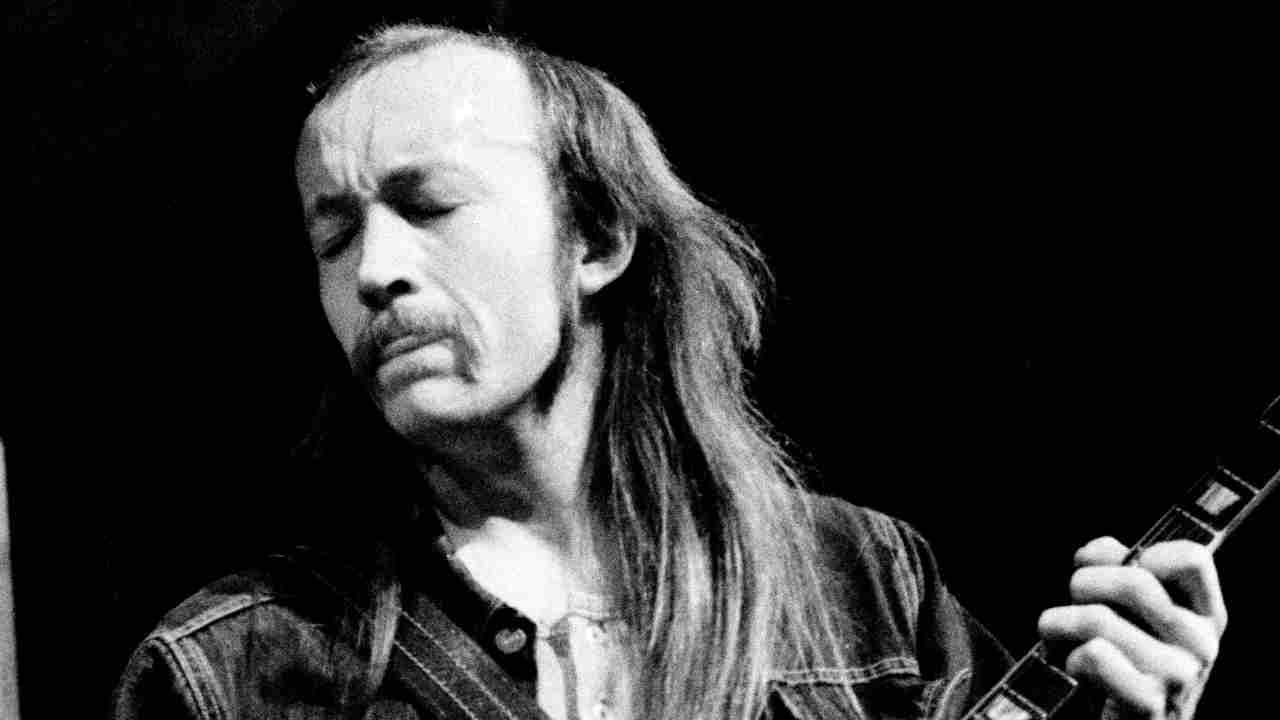

Shooter Jennings: Meet the outlaw country renegade with a taste for darkness

Shooter Jennings talks about getting out of his famous father’s shadow, paying his dues, conspiracy theories and why he’d “kill to go” to one of David Icke’s lectures

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

As the son of Nashville royalty Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, Shooter Jennings could easily have followed the prescribed route into country music. Instead, he headed to LA and formed rock’n’roll miscreants Stargunn, before embarking on an adventurous solo career that’s found room for metal, southern rock, outlaw country and, on this year’s Countach (For Giorgio), Moroder-like electronica. Timed to coincide with the US presidential election, Jennings is reissuing his 2010 album Black Ribbons (complete with vinyl, CD and unreleased tracks), a concept album about a totalitarian state in which free speech is forbidden, featuring horror author Stephen King as a freedom-fighting DJ. He explains all to Classic Rock…

Why are you re-releasing Black Ribbons now?

I don’t really subscribe to any politics or believe in any of it, but now we’re in this situation where freedom of speech is getting drowned out and the media is filtering the left and right, wielding its power. It’s such a crazy time. The album did pretty good first time around, but it really didn’t have the reach. So I decided that we need to put this out on election day and make a statement with it. The message is: don’t let all the bullshit get you down. Don’t let these people distract you from what’s important – your family, love, local community.

Was Black Ribbons liberating to make?

I had this fictional band [Hierophant], and it was like wearing a mask of some sort. I was able to create this thing where I could be anything. And of course that record had a lot of rejection, especially on tour. Some radio stations refused to promote my gigs because they thought it was an anti-American album. We had people throwing shit at us at shows. People were misunderstanding the Stephen King stuff as an anti‑patriot thing.

Is it true that David Icke was a big influence on Black Ribbons from a conspiracy theorist angle?

It actually started because of him. I heard David Icke on an American radio show called Coast To Coast AM when I was headed to Los Angeles to do Black Ribbons and it really blew my mind. He was like the gateway drug, and I started reading his books. It was pretty much my waking up to what’s really going on with the media, corporations and the elite. People laugh at David Icke’s reptilian theory [Icke asserts that the world’s elite are descended from a race of giant, shape‑shifting lizards], but whether or not you believe it, to me he’s very smart. And he’s got a lot to say. I would kill to go to one of his lectures. The thing about Black Ribbons is that I went into that world and believed everything that I read, no matter what. Then I got into studying the bloodlines of the Bush family and the Windsor family, tracing them back and finding all the coincidences. Even the Saudi Arabian connection with Bush and 9⁄11 has suddenly become exposed to the public, after all these years of conspiracy theories. Back when we did Black Ribbons, everybody still believed all the bullshit.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

- The 10 Essential Country Rock Albums

- Marilyn Manson, Shooter Jennings in video for Bowie cover

- The six best new artists making country rock their own

- The 25 best country rock songs of all time

You left Nashville for LA at the start of your career. Was there just too much baggage for you at home?

Yeah. I didn’t want to be ‘Waylon’s kid’, man. I wanted to go somewhere where they didn’t know who I was, a big city where rock’n’roll happened. When I got to LA I was just like anybody else. That was great for me, because I had to grind for ten years just to make my own voice be heard.

Did Stargunn enable you to experience the rock’n’roll lifestyle?

I wanted it so bad. But it was also a way for me to pay my dues, fail, make the wrong choices, learn how to play live with a band and develop my songwriting. That was like college for me. So when it finally came time to step out on my own, I wasn’t wet behind the ears – I’d been through a lot.

Your record label, Black Country Rock, takes its name from an old David Bowie song (on 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World). How much of a touchstone was he for you?

I was fourteen or fifteen years old when I discovered Ziggy Stardust. I listened to that record every night when I went to sleep. Throughout his career, every record had a new persona. To me that’s the greatest kind of artist. He was like a lantern in the fog. On the day he died I went to a bar, got drunk and started crying. I was heartbroken, numb. It was probably the same for my dad when Hank Williams passed away.

What’s your first musical memory?

I remember being on the road with my dad, and in the studio with him, when I was little. The first time I heard something I really liked was Guns N’Roses, at a friend’s house. After that it was Nine Inch Nails. I remember going to see Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson when I was 13 and thinking, “This is dangerous. I wanna be wherever these people are.” I’ve always been infatuated with the dark side of things, the exploration of the unknown.

Does it ever feel weird that your band, The Outlaws, were also your dad’s backing group?

Oh yeah. But we’re not playing Waylon’s stuff, we’re playing mine. It does get a little weird sometimes, because I didn’t get into this to copy my dad’s thing or even carry it on. Of course, there are things I’ve done along the way that are a nod to him, but I’ve always been my own artist. I’ve been touring with The Outlaws for three years and it’s coming to an end with them, so it’s bittersweet. I have some new steps I’m going to be making for next year. It’s been very fulfilling, but at the same time I know I have something new to offer that doesn’t have anything to do with my dad. The next record is going to be a big step. Hopefully it’ll open some more people’s minds.

Black Ribbons is released on election day, November 8 via Black Country Rock Media.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.