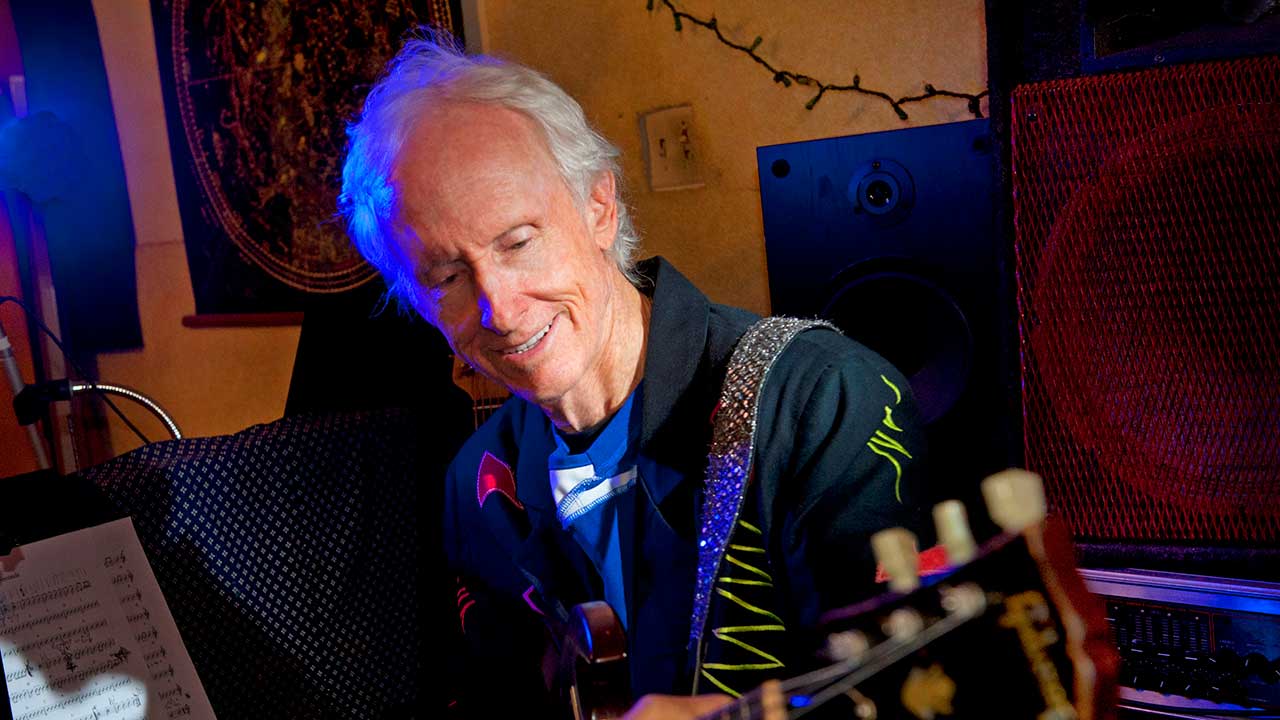

Robby Krieger interview: life in The Doors, the wonder of acid, and dealing with crazies

Robby Krieger might have become a trumpet player. Instead he swapped the horn for guitar, joined The Doors and became part of one of rock's most influential and legendary bands

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The voice of Robby Krieger on the phone sounds like Travis in Paris, Texas. One note. Bone dry. Exhausted and burned by the whole sentenced-to-life séance that the story of The Doors has become. Yet quite cheerful.

Robby was always the most easy-going in The Doors. After Ray Manzarek, who spoke of golden vibrations yet jumped at shadows. Far behind John Densmore, who was still calling Jim “a psychopath, a lunatic” the last time anyone heard from him. Jim Morrison was all fucked-up of course, but in a good way, at first. Then in a bad way, soon after.

“When he was doing the acid and marijuana, he was great,” Robby says. “No problems. It’s when he started drinking, then he would just turn into an asshole sometimes.”

Jim saw himself as a disrupter; Robby was a maintainer. You build but you do it from a place of peace. Robby was a real musician. That’s how it was done. Jim couldn’t play, had no patience for the studio, saw himself as Rimbaud on the loose in Hollywood.

Yet the two opposites attracted when it came to making up stuff together. Jim with his pages and pages of neo-Beat poetry, Robby with his transcendental guitar playing.

I’ve been reading about your childhood, where you came from, and it sounds like you came from a really nice family. Tell me if any of this is wrong. Your dad was an engineer? You grew up in the 1950s listening to classical music?

Yes. Not only classical, but pop as well. My mom liked Frank Sinatra and stuff like that, and my dad liked classical. But we had all kinds of records at my house, like flamenco records, stuff like that. Some jazz, even boogie-woogie.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The flamenco stayed with you, became a characteristic of your style in The Doors?

Yeah, for sure. I didn’t really get into that stuff until I was maybe thirteen, fourteen years old, but my dad had those records in the house. The first one I really liked was Peter And The Wolf.

Is it true that you once broke your record player, which meant you couldn’t keep listening to Peter And The Wolf, and that’s when you began listening to the radio, which got you into more popular stuff of the day like Elvis and Chuck Berry?

No, that’s wrong. I broke a Peter And The Wolf record. That started me listening to other records.

Your first instrument was a trumpet. That got old quick and you took to playing on your folks’ piano. What brought you to the guitar?

The reason I started trumpet is because my friend at school was the guy that played the bugle and I thought we could be a team. Another friend up the street had a guitar, and whenever I’d go over there I’d plunk around on it, and I really, really, really liked it. I just immediately had something that I liked. So yeah, that was how it got started. I was probably thirteen.

Did you have a guitarist in your head that you were thinking of, who you wanted to be?

No I didn’t. I didn’t have any thoughts like that. I just knew I liked that guitar. I liked the sound of it.

As a teenager you were sent to board at the private school Menlo in Menlo Park because your folks didn’t like the company you were keeping. True?

I didn’t want to go, but I kept getting in trouble at home and wasn’t doing very well [at school]. We would do destructive stuff. Like there was this housing development they were building above my friend’s house, and we didn’t like that, so we went up and left the water on all night in the kitchen.

And crazy stuff; driving tractors around in the middle of night. But Menlo was pretty cool for me because there was kids there from all over the country, and they all brought their records with them and I really got turned on to a lot of cool records at that school.

Were you a rebellious kid?

Yeah, a little bit. A little bit.

Did you ever get into trouble with the law?

Yeah, later. I got busted for pot a couple of times.

That was almost a badge of honour in those days, right? If you were smoking pot or dealing in pot, like you were as a teenager, you were one of the cool kids.

Not really. Not really.

No?

Yeah. But still, then you were really paranoid, because if you get caught twice, then you go to jail for sure. So I was just lucky the second time. They didn’t have enough evidence and let me go. The summer after Menlo is when I first got caught. And then, again about a year later, when I was in college.

You were at college in California in the mid-sixties. Was there ever a better time and place to be young? The age of consciousness-raising. Free love. Drugs, back when they still did you good. How aware were you of that?

Well, all that’s really part of it. Even before it was popular we took LSD and marijuana. That’s when I was up at Santa Barbara – my first college year was at UCSB. Probably seventeen.

That must have been particularly powerful stuff in those days?

Yeah, it was the real stuff. It was really good. I had that stuff once, and then it was never as good again because that was the real stuff. For a lot of people, that first acid trip was a real turning point in their lives. They couldn’t really think about things the same way afterwards.

Did you have a similar experience?

Definitely. In fact I became kind of like a Timothy Leary-type guy. Yeah, get acid. Give it to all my friends, and we’d have a big bunch of us who would take it every weekend. Until one time I gave it to this one friend and he freaked out. And then, he got all crazy and I realised, uh-oh, I shouldn’t be giving this to people, some bad things can happen. At that point I turned to transcendental meditation.

How old were you when transcendental meditation happened for you?

That was just before The Doors, so I was probably eighteen. Yeah, this was before The Beatles did transcendental meditation. In fact we were the first ones that met Maharishi in the United States. He first came over, sixty-five maybe, sixty-six. My friend’s brother had gone to India to find a guru, and he actually met Maharishi and talked him into coming back over here [to LA]. The first meeting we had was up at my friend’s house, and it was Maharishi and maybe twelve people. And out of those twelve people it was me, John Densmore and Ray Manzarek. Unbelievable.

And have you stayed with it, the meditation, throughout your life?

Yeah. Not every day, but definitely still do it. Did that replace the acid? I still did acid, once in a while, but pretty much the idea was to replace it. Of course, it wasn’t as… dramatic. Ray thought it would be. Ray says: “You know that Maharishi is talking about attaining bliss.” He always used that word, ‘bliss’. And so first, after we got started with TM, we had another meeting, and Maharishi said: “Okay, how’s it going with everybody?” And Ray raises his hand and he goes: “No bliss.” He thought it would happen after the first-time sessions.

When you started The Doors, was it like: “We just want to get a song in the charts”?

No, no. We definitely… We thought we were as good as the Stones or anybody, because Jim had these amazing works that were nothing like anybody had ever put in rock’n’roll songs. You were all accomplished musicians.

Did you ever trip out while you were playing?

A couple times. A couple times. You mean on acid? Well, Jim and I did. It was too crazy. It’s like you don’t really… It’s too hard to play the songs correctly when you’re on acid. For Jim it wasn’t so hard, he could just make stuff up, but the musicians had to be a little more together

Did you ever listen back to Doors music while you were tripping?

Oh, yeah. That was the best part. It was visual. It was in the room. When I took that first trip, we were listening to Paul Butterfield, among other things. And boy, that was great.

And then as a songwriter, you were the guy who came up with so many of the important songs in the story of The Doors: Light My Fire, Touch Me, Love Me Two Times. That was all you. Then it was just you and Jim on The End, People Are Strange, Peace Frog. Was that something you worked on, or was it a gift that you were able to write these beautiful songs?

I guess it was a gift. At first, Jim was writing the songs because he had all these great works, and I had never really written a song. But at one point he says: “Hey, we don’t have enough originals.” Because we were doing cover songs as well at that time. He said: “Why don’t you guys write something? Why do I have to do all the work?” So the first one I did was Light My Fire.

Wow. That’s setting the bar pretty high.

Yeah. Yeah. It was downhill after that.

If not quite ‘downhill’ then certainly circuitous. Six albums in five years, all stone-cold classics – even the duff parts. Yet it wasn’t until Jim Morrison died, in squalid circumstances one hot heroin-filled night in Paris in 1971, that the true story of The Doors really began.

A few fallow years in the doldrums of the mid-70s, followed by a sudden surge of Doors-related exoticism.

Wanna take a ride? Robby did.

Is it true that Jim was jealous that you had written all of Light My Fire?

No, I don’t think so. He loved singing. He usually got the best response [at Doors shows] if any of his songs were being played.

Ray was always so evangelical about Jim. He kept the myth going. John would get pretty pissed at the whole thing. But what about you? What was your own relationship with Jim?

Well, it was fun because I was the youngest and Jim was my older brother-type relationship, so he and I got along pretty well. Especially at first, we were like brothers. And then slowly, slowly, he’d start hanging out with these assholes and we grew further apart. But we always got along great.

That must have been very tense and difficult for you sometimes?

Yeah, of course. Especially on the road. When you’re on the road, travelling together, and you never knew what he was going to do. But the music always came first, so he never missed a gig. He’d always complain that we were late to rehearsal. “You guys have girlfriends and stuff,” he’d say. “I’m doing it twenty-four hours a day.”

And those big moments, like Miami, the infamous 1969 show where a wasted Jim pulled out his penis for all the world to see. Or the time in sixty-eight when he was tripping on stage at the Hollywood Bowl? At the end of those nights, how would you deal with it?

I always… I was probably easy come, easy go. It was the sixties – anything went, you know whatI mean? Pretty fun. So no, it didn’t bother me as much as John, I’m sure. And Ray, we all put up with him because of the music. John actually quit the band one night. And of course he came back the next day. Never got to that point for me. It was always worth all the bullshit because of the music.

By the time Jim went to Paris, in 1971, I heard you guys had had enough and that you were already planning for a life without him in the band. Is that true?

No. No, when he went to Paris we fully expected he would come back at some point. Maybe not for months or something, but when he left we kept rehearsing. And we kept writing songs, which turned out to be that next album after Jim died [Other Voices, 1971]. Yeah, we fully expected he would be back, because he lived for music and he always talked about being a poet and stuff. But that was really never enough for him. He had to be on stage. Even when he was in Paris he would go and play in these clubs and with these guys.

Do you buy the whole Jim dying in the bath story, or are you familiar with the more recent stories of him dying of a heroin overdose in a Paris club?

I don’t really know, but I wouldn’t be surprised if heroin had something to do with it, because when you’re a drinker you can’t do heroin. Jim was a drinker. Do those two together and you’re in trouble. And Jim was not well. When he left he had this horrible cough and he just wasn’t a hundred per cent. So if somebody gives you some heroin, you start drinking some whisky, and maybe he did die. Maybe the bath was too hot, I don’t know. Some people say he died at the club, and then they brought him back to his house and stuck him in the bathtub. That sounds possible to me.

How did you feel about the whole ‘Jim is still alive’ schtick?

I used to love talking to Ray, and he would always say: “I wouldn’t be surprised if Jim turned up.” And I used to think: “Come on, man, you don’t really believe that, do you?” That was pretty much bullshit. Yeah, he didn’t have to do that, and that I think really got him and John in a bad… John was really just about that.

After Jim died, what made you decide you wouldn’t get a new singer? Because you tried a few guys out. What stopped you in the end?

Yeah, we did. Well, we were going to get a new singer. We all moved over to England. We were starting to try a couple guys out. And Dorothy, Ray’s wife, who was pregnant at the time, started going nuts, I guess from the hormones or something, and she wanted to go home. And then the three of us weren’t getting along. John and I wanted to do some more hard rock. Ray wanted to do jazzier stuff, so he got pissed off and just left.

Then comes the moment in 1978, that extraordinary posthumous album An American Prayer, followed by the famous Rolling Stone issue with Jim on the cover and the strap line: ‘He’s hot, he’s sexy and he’s dead’. Suddenly you were cool again.

Well, I think more than that, it was when Danny Sugerman wrote his book [No One Here Gets Out Alive, 1980], and then the Oliver Stone movie [The Doors, 1991] came out. But that album was one of my favourites, for sure. Definitely, it was… Yeah, I love that stuff.

Do you think if he’d lived you might have got to a place with Jim where you made more records like An American Prayer?

For sure, yeah. That was sort of the idea in the first place. It was poetry, and jazz, and I bet you that would have been the direction. Yeah. That was the whole idea behind it – like I said, poetry and music together. Guys used to do that back before us. Allen Ginsberg and those kinds of guys, they would do poetry and they might have some jazz playing with them. But for a pop group to do something like that, it hadn’t really been done.

Also, Ginsberg didn’t look like the young Jim Morrison, did he?

I guess not [laughs].

Another landmark in the creation of The Doors’ myth was the use of The End in Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now.

Yeah, that was amazing. [Coppola] actually had the right to use any Doors song, all of the songs, if he wanted to. He said later that he tried Light My Fire and all these other songs in various parts, but… they just didn’t fit. The End was perfect because there was so much instrumental parts. That first scene with the helicopters was amazing. When Jim and I wrote that song, at first it was just a little love song and it was this beautiful friend. It wasn’t none of that other stuff. But as we played it every night, he would add stuff. We’d get longer and longer. But I always had the idea for that song to make it like an East Indian sounding [guitar]. Nobody else was really doing that on the guitar that much.

After the movie, the book, the Rolling Stone cover, the Prayer album, we’re in this realm where The Doors story has become a mythology. Did you recognise yourself in Sugerman’s book, or was it him tripping out on his own kind of fantasy island?

It was some of both. Mostly his own. What I didn’t like was how he puts words into Jim’s mouth, you know? He would write down conversations that might have happened in his mind, but not for real. Yeah. Oliver Stone did the same thing. He wrote the dialogue in that movie. He had a good writer, but for some reason he didn’t like it and he ended up doing it himself, which I think was a mistake.

What did you make of Stone’s movie when you saw it?

Well, the music parts were really good. Val Kilmer [who played Morrison] was good. It was great. ButI actually worked on the movie as a musical advisor, so I was there when they did all the concert parts, and they were very right on. But just the whole thing with Jim and Pam [Courson, Morrison’s girlfriend at the time of his death], and all that stuff, it wasn’t based on reality.

Then there was the shock collaboration with Ray in the early 2000s, initially billed as The Doors Of The 21st Century, with Morrison disciple Ian Astbury from The Cult on vocals. Ian is obviously totally in love with the whole Jim thing, and actually does a pretty good version. What was the deal there?

Well, yeah. Before that, I hadn’t played Doors music for years. I was doing jazz in my Robby Krieger Band. I had my kids in the band and stuff, and so I was having fun doing that. But then I started seeing these Doors tribute bands popping up all over the place. And some of them were pretty good. I used to sit in with them once in a while, and I would see how much fun everybody was having. And little by little, I would just put a couple of Doors songs into my set.

And then at one point, I was talking to Ray and said: “Shit, why don’t we go back out and do The Doors? These tribute bands are doing great, and we could do it a lot better than that.” And we asked John to do it, but he didn’t want to do it, so we ended up getting [Police drummer] Stewart Copeland and we went out and did a couple of shows, and they were great with Ian singing.

Why didn’t John want to be involved?

I really wish I knew. He says… I think it’s because he couldn’t get along with Ray. He probably figured Ray would try to take over. Because when Jim was around, Ray was held in check, do you know what I mean? You could tell after Jim was gone, Ray became kind of the spokesman of The Doors, all the stuff he used to say about trying to make it like Jim wasn’t dead and stuff. It was kind of creepy, because he was obviously just doing it to try to keep the sales up or something. I think that’s what John was thinking. But after really talking about it with Ray, he just loved The Doors and he didn’t want people to forget. Maybe he went too far.

You could say that if he hadn’t done that and he hadn’t been such a torchbearer for the legend, The Doors wouldn’t have to stayed as mysterious and glamorous.

And maybe Danny wouldn’t have wrote the book, who knows?

Now, when you talk about the influence The Doors have had, it would be easier to try to think of a band that wasn’t influenced by The Doors, which must be very gratifying for you?

Yeah, it is. It’s kind of cool, for sure.

And what about the crazies? Jim brought out the crazies. How did you handle it?

We’ve had plenty of those. Plenty. There was one guy after Jim died, he used to hang around our rehearsal place. We called him Cigar Pain, because he actually stuck a lit cigar down his throat to make his voice sound more like Jim’s, he said. He was really out there. And then there was a guy who stopped me in my car one time. “Hey, are you Robby Krieger?” “Yeah.” He says: “We have to take acid and die together.” I said maybe next week.

Because of that sort of thing do you take extra precautions when you’re travelling around?

Well, yeah, and I’m always on guard, but it’s… And there’s this girl. If you see the new movie, Break On Thru [Break On Thru – A Celebration Of Ray Manzarek is melding a 2016 tribute performance in LA when Robby and John were joined on stage performing Doors songs by various members of the Foo Fighters, X, Stone Temple Pilots and Jane’s Addiction, to name a few], at the end, when we all do Light My Fire, you notice there is this blonde chick in the frame. Yeah, well, she just snuck in there somehow, didn’t even have a ticket. Somehow, she sneaks on stage when we’re doing Light My Fire. Oh my God. And then she showed up to the night when I was playing with Miley Cyrus. Did you hear about that?

Please do tell.

This guy is re-doing the original Morrison Hotel, yeah? So he put on this big wingding at the Sunset Marquis hotel to promote his thing, and he got a bunch of cool musicians together and we did a bunch of Doors songs. Miley did Roadhouse Blues and Back Door Man. I don’t know who did Light My Fire. Oh my God, who was that guy? I can’t remember. Anyway, a bunch of people were there. And there she is [the blonde chick]. She somehow got backstage again, and she had the flu or something and she could barely talk. She was getting in my face, and I’m: “Get away! Get off!”

I’m laughing, but it’s just too much, isn’t it?

Yeah. They’re everywhere, you know?

Did you ever go to Jim’s grave at Père Lachaise in Paris?

Oh, yeah. I’ve been there plenty of times. Yeah. In the movie, it showed where John and Ray and I were there. Did you notice?

I just wondered if you ever went there on your own?

Yeah. Every time I go to Paris I drop by there, check it out. Jim gets some interesting people hanging out there with him. Yes. It’s kind of cool, all the people that are there. All the famous people. And Jim loved that place. He always said he wanted to be buried there.

Unlike almost every other rock star survivor of the late 60s/early-70s, Robby Krieger still makes new music, rather merely recycling the past. His new solo album, The Ritual Begins At Sundown, is his first for 10 years. And it sounds unlike anything he’s done before. It’s jazz and funk and even pop, but built in a rock universe.

How long did it take you to make the new record?

It took quite a while, actually. It was about three years. Yeah, my buddy, Arthur Barrow, who is a bass player, he used to be Zappa’s guy. I’ve done stuff with him for years, ever since my first solo album. I’ve known him since the seventies. We really get along together musically. So we start writing some stuff, and then we got a couple of the other guys from Zappa’s old band, Tommy Mars, the keyboard guy, and a bunch of really great musicians around town, and we tried. We wanted to write stuff together. One guy might have an idea for something, and then we would all contribute after that. So it was kind of cool in that regard.

It’s a proper jazz record as well, isn’t it? You can all really, really play, and you’re playing together. You’re listening. You’re taking your cues. You’re going with it.

Exactly, yeah. That’s what good musicians do. It’s not just guys shredding, which happens too often. Jeff Beck is my hero. He’s just gotten better constantly, and I want to be like that. I want to try some new stuff, all the time, and just not rely on the old stuff.

The Ritual Begins At Sundown is out this week.

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.