Maritime mischief: pirate radio's rock'n'roll revolution

Superstar DJs, murder, mayhem... and swearing parrots. This is the story of how pirate radio sparked a rock’n’roll revolution in the '60s

John Lennon supposedly once said: “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” Yet even after The Beatles had become the biggest pop cultural phenomenon of the 20th century, if you tuned your radio to the BBC on any given weekday you’d be under the impression that rock’n’roll never happened. Even The Light Programme, with its anodyne blend of chat, comedy, soap and easy-listening favourites, offered a cultural landscape in which rock’n’roll was welcome only briefly for an hour or two at the weekend, as if the kids were being left unattended for a short period of play while the adults had a lie-in.

In many ways, rock’n’roll came of age in 1966, but the BBC still seemed to regard this pop music lark as a vulgar fad, which, if you ignored it for long enough, would eventually go away. By that time, though, even the government of the day were noticing that the lunatics were rapidly taking over the asylum. By boat, bizarrely enough.

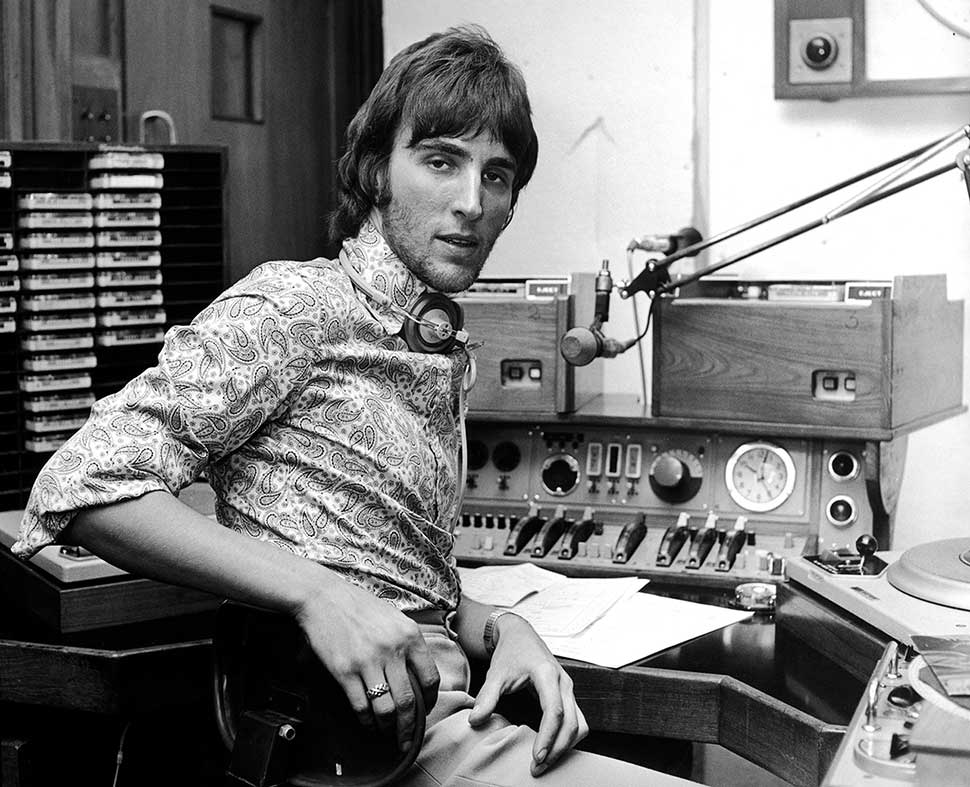

And it was a simple case of supply meeting demand. A young Johnnie Walker, then a car salesman, keen pop picker and aspiring DJ, was one of many frustrated listeners.

“Even when the BBC did play the music I liked, they wouldn’t play records longer than three minutes or so – they refused to play House Of The Rising Sun or Like A Rolling Stone, for instance. I tried to get [Europe-based commercial station] Radio Luxembourg, but it was difficult to pick up and had this famous ‘fading out’ problem… In the end I hung a great wire cable off the roof of my house in Birmingham, to make an aerial and attach it to my radio, and that’s when I managed to pick up the pirates.”

He wasn’t the only one. By 1966, stations such as Radio London, Radio Caroline and ‘Swinging’ Radio England, operating from ships anchored a few miles off the Essex coast, had met the demand for 24-hour rock’n’roll radio, and they built audiences to seriously challenge the establishment. By the beginning of 1966, the top radio stations were pulling in more than eight million listeners.

One appeal of the pirate stations was the relative freedom their DJs had to play what they liked, in contrast to the BBC and Radio Luxembourg, over whom Britain’s major record labels seemed to have a stranglehold. “Four majors dominated the market,” Walker recalls. “I think it was EMI, Decca, Pye and Philips. The BBC would only play ‘established artists’ [i.e. artists on those labels]. Radio Luxembourg would also sell thirty-minute chunks of airtime, so you’d suddenly have the Decca Records show.”

Pioneering independent labels such as Island and Immediate couldn’t get played on the BBC, nor could they afford to buy commercial radio airtime. Irish pop impresario Ronan O’Rahilly was one of many industry schemers who hit this broadcasting brick wall when he tried to get the rhythm & blues acts he managed, such as Georgie Fame and Alexis Korner, on the radio. So he raised the money to set up his own floating radio station anchored just outside the three-mile boundaries in which British laws apply. Back home at his parents’ ferry port of Greenore in Ireland, he had an old passenger ferry kitted out with a huge radio mast and transmitters.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Once they’d set sail for the mouth of the Thames, Essex coastguards wondered what this vessel full of long-haired layabouts was loitering about for, until all was revealed with Radio Caroline’s first broadcasts on Easter Saturday 1964.

By 1966, Caroline had been joined in a curious row of ships stationed less than a mile from each other, while in the Thames Estuary near Whitstable you could find similarly maverick operations, who had followed Screaming Lord Sutch’s Radio Sutch and established stations such as Radio City, King Radio and Radio 390 on wonky old army forts built on stilts out in the North Sea. Other stations dotted around the coast served Scotland and the North. All claimed to be operating in international waters and therefore didn’t need a licence from the British government.

The result of all this was that as 1966 dawned, the stations that were truly reflecting the seismic upheavals in the music scene were the pirates. And you could tell there was a world of difference between the establishment and the rebels before you even heard the music they were playing; their presentation style aped the freewheeling, jingle-filled approach of American and Australian Top 40 stations – which explains why many of the DJs were from those parts of the world. The difference between this style and the established way of doing things reflected the generation gap the pirates were capitalising on. This had already been brought home to Walker when he’d managed to get an audition with Radio Luxembourg the previous year: “I had to DJ from a script, whereas I was used to ad-libbing. It was all very formal, no spontaneity at all. At the end he said: ‘You haven’t got the voice, you haven’t got the personality, you’ll never be a DJ as long as you live.’ When the pirates started it was a completely different way of broadcasting. Nobody had ever heard the like of it. And young people really responded to it in a big way.”

By the beginning of 1966, Radio London, featuring such future household names as Tony Blackburn and Kenny Everett, had established a Top 40 format that made it the top-rated station, and Caroline bosses were keen to regain the upper hand. One of the hip young gunslingers they turned to was Mike Pasternak, aka Emperor Rosko. He joined Radio Caroline South after a stint presenting in France and, having previously DJ’d at sea while in the navy, he was more than happy to be back afloat and given the freedom to let loose with his high-energy, wildly enthusiastic brand of broadcasting. “I’d been the naval version of Robin Williams in Good Morning Vietnam,” he says, “so it wasn’t difficult at all to be DJing on a ship.”

The star of Rosko’s show was his pet mynah bird, Alfie, whom he taught to chirrup “Sounds fine, it’s Caroline,” at random intervals.

“He was awesome,” Rosko remembers. “He loved it on board. But he could be a little dangerous, too. Some of the other DJs thought it would be clever while I was away on shore leave to teach him to say ‘fuck’ and other choice expressions. When it happened I used to say: ‘Oh, did he say ‘fudge’? What a funny way to say ‘fudge’!’ Luckily he had a certain look on his face when he was about to say it, so I got very quick with my mic fader.”

Johnnie Walker was similarly innovative in capturing listeners’ imagination. Sections of his 9pm-to-midnight show included such risqué features as ‘Frinton Flashers’, wherein he communicated with listeners in their cars on shore by asking them to flash their headlights in response to his questions, and invited lovers on shore to ‘Kiss In The Car’ at 11.30pm and enjoy the ‘10’o’clock Turn On’, in which a particularly lascivious slice of soul or bluesy rock was played.

“It was a bit like The Beatles and the Rolling Stones,” Walker says in his autobiography. “[Radio] London was The Beatles – slick and neat, the radio station you could take home to your mother for tea. Caroline was definitely the Stones – scruffy, anarchic, non-conformist and rebellious… It was there to give freedom and expression to the creative artistic explosion that was the Sixties.”

The pirate DJs rapidly became folk heroes – close to pop stars in their own right in some cases. Yet the notion of floating orgies awash with booze and birds is 90 per cent myth, despite what the 2009 British comedy film The Boat That Rocked suggests.

“I started on Radio England,” says Walker, “and they’d built it so fast there were no bunks – we had to sleep on the floor. The North Sea could be pretty rough, so it got pretty scary at times.”

During rough weather it was far from unknown for DJs to break off from their spiel to vomit, due to the inevitable bouts of seasickness. “I think people enjoy hearing us go through it,” former pirate jock Tony Blackburn told The Observer in December 1966.

Meanwhile, life on some of the more fly-by-night operations could be very hazardous indeed. The late blues DJ Mike Raven told of being threatened by heavies from rival operations, station owners’ boats being sabotaged by rival gangs (one such ‘tender’ sank in 1964, claiming three lives in murky circumstances), and arriving at the nascent Radio King on a Thames Estuary fort to find three men literally starving to death, their transmitter having broken three weeks previously, rendering them unable to call for help, and their tinned rations 10 days gone. Nonetheless, on the ships the job wasn’t without its perks.

“[In summertime] we were surrounded by sailboats pretty much all the time,” says Rosko, “and they would sail around and wave, and the girls would lift up their tops to show us their… assets. Occasionally they’d get invited on board if the weather was permitting.”

“Women were officially forbidden on board,” Walker reckons, “but in the summer, when a few little yachts would come out to the ship and there’d be girls among them, if the captain allowed it – some did, some didn’t – they’d come on board and have a look round the ship. We’d give ’em ‘the tour’.”

In his autobiography, Walker recalls a common trick was for a crew member to take the boyfriend to look at the ship’s engines while the DJs ‘entertained’ his other half. And once the DJs took their shore leave every couple of weeks – and got past the sometimes troublesome attention of customs officials (“Tony Blackburn got the whole of his toothpaste tube squeezed out one time – they were convinced we were smugglers”) – they’d be welcomed into the beating heart of Swinging London. “We’d hang out with the bands in clubs like the Bag O’Nails and the Speakeasy, and we were accepted among them,” says Rosko.

Meanwhile, the atmosphere of competition and innovation on board the pirate ships mirrored that found among the artists they championed.

All the same, legally dubious activities such as those the pirate stations were indulged in was bound to attract the interest of some equally dubious characters. Scams were common, as were various forms of the payola Ronan O’Rahilly had originally set up Caroline to overcome. Radio London negotiated the rights to the B-sides of many of the hit singles they played, meaning they got half the royalties, while Caroline investor Philip Solomon insisted their stations play easy-listening artists such as The Dubliners and The Bachelors on his own Major Minor label. Thankfully, by that time some DJs were too popular for anyone to order around.

“I didn’t care,” Rosko admits. “I didn’t need the job or the money, and I was already pretty well known, so I wasn’t scared of not playing the crap records on Major Minor. I just played everything I liked and I loved doing it.”

But the shady deals turned very sour in the summer of 1966 when Reg Calvert, founder of the fort-based Radio City station, accepted an offer from Radio Caroline investor Major Oliver Smedley to provide a new transmitter for Radio City in return for a share of his business, only to find that the mast was 30 years old and virtually useless. He told Smedley he was now going into business with Radio London instead, and ignored Smedley’s demand for £10,000 to pay for the transmitter. Smedley sent a gang to board Calvert’s fort to disable his radio operation, after which Calvert visited Smedley at the latter’s Essex home on June 21. A row erupted and Smedley shot Calvert dead.

Smedley was later acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defence, but the incident lent fuel to the government’s view that pirate radio was an unlicensed den of rampant commercialism bound to attract the criminal element. The pirates weren’t paying copyright fees to the artists they played, nor did they observe the Musicians’ Union’s strict limits on ‘needle time’, designed to keep their members in jobs rather than being replaced by records. And the pirates were said to be a danger to shipping because of the issue of their broadcasts obstructing maritime radio signals.

“We had a great freedom on Caroline,” says Walker. “Every other record you played had to be a Top 40 record, but then the other ones could be anything you liked; it could be a new record, it could be an oldie, could be an album track.

“You had all this competition among the bands, and there would also be competition between the pirate stations. We’d be testing out new singles to see how they go, try to get higher chart position than the songs our rivals were playing. It made for such a fertile time.”

The rivalry got decidedly underhand at times too. Before the newly launched Swinging Radio England began broadcasting in May 1966, they dropped anchor next door to Caroline South’s ship the MV Mi Amigo. Emperor Rosko hatched a fiendish plan: “Radio England pulled up alongside us one day, and they were testing their signal with all these great jingles. So I said: ‘Roll the tape!’ We recorded all these jingles, and spent the night editing out ‘Radio England’ and putting ‘Radio Caroline’ in instead.” As a result, when listeners heard the first Radio England broadcasts, they accused the newcomer of stealing their jingles from Caroline, and had to pay for a new set to be made.

“They went insane,” Rosko continues, “flying around threatening writs, but Ronan [O’Rahilly, Caroline boss] said: ‘Well, we’re pirates – that’s what pirates do!’”

Nonetheless, there seemed to be relatively little appetite for curtailing the pirates’ lovably roguish activities outside the head offices of the major record labels, the BBC and the cabinet. Even when Radio Caroline’s ship the Mi Amigo lost its anchor in a storm in January 1966, drifting into British waters and running aground, they weren’t prosecuted. And opposition from the record industry didn’t really amount to much in practice.

“Sir Joseph Lockwood, head of EMI, was also dead against us and the whole idea of 24-hour music radio,” Walker says, “because he thought if radio stations played records all day long people wouldn’t go out and buy them. So he was always pressuring the government to ban us, yet at the same time, EMI’s pluggers were rushing round to the pirate stations’ offices with half-a-dozen copies of every record!”

“Up until then we had a lot of public support,” reckons Walker, “but the Calvert thing was the beginning of the end.”

The Marine Broadcasting Offences Act was introduced in parliament, but politicians knew that the sinking of pirate radio would be wildly unpopular unless there was something to replace it. So the BBC caved in to government pressure, and put plans in place for a dedicated music station in the shape of Radio 1. It kicked off its programming with one of the many reformed pirate DJs, Tony Blackburn, in September 1967.

Johnnie Walker and Robbie Dale were among the DJs who persevered after the ban on the defiant Caroline – Walker, a keen champion of US soul, played Otis Redding’s I’ve Been Loving You Too Long (To Stop Now) the night the new law came into force – after the other pirates gave up the ghost, but lack of advertising revenue meant they lasted less than a year.

By that time, though, pirate radio had already pointed towards the future of rock radio. It was natural that the DJs’ relative freedom would open the door for the album-oriented rock that followed The Beatles’ ground-breaking long-players. That process was accelerated by shows such as John Peel’s small-hours 1967 show The Perfumed Garden on Radio London. Meanwhile, influential rock DJs such as Tommy Vance had also learned their trade on the ships. Vance would later play a pirate DJ in the scene from Slade’s 1975 film Slade In Fame when the band board a pirate radio fort and have shots fired at them, in a scenario loosely based on the Calvert/Smedley feud.

“Radio 1 had a big impact, and a signal that we [Caroline] couldn’t compete with.” Johnnie Walker reckons. “But all the sixties bands were enormously grateful to pirate radio.”

“Pirate radio was phenomenally important as promoters of new music,” Rosko agrees. “People say The Beatles and Stones and The Who wouldn’t have achieved the success they did without it, but who can tell?”

Both Rosko and Walker later joined Radio 1, the latter only after being blacklisted by the Beeb for a year, demanding he remain unhired “until the taint of criminality subsides”. But the work they and their colleagues did in that revolutionary year would change music forever.

Johnny is a regular contributor to Prog and Classic Rock magazines, both online and in print. Johnny is a highly experienced and versatile music writer whose tastes range from prog and hard rock to R’n’B, funk, folk and blues. He has written about music professionally for 30 years, surviving the Britpop wars at the NME in the 90s (under the hard-to-shake teenage nickname Johnny Cigarettes) before branching out to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent and magazines such as Uncut, Record Collector and, of course, Prog and Classic Rock.