“Metallica would jam on their stuff in rehearsals, songs like Black Night and Highway Star”: Lars Ulrich on his lifelong love of Deep Purple and the genius of the Machine Head album

Lars Ulrich is a lifelong Deep Purple fan – and here’s why

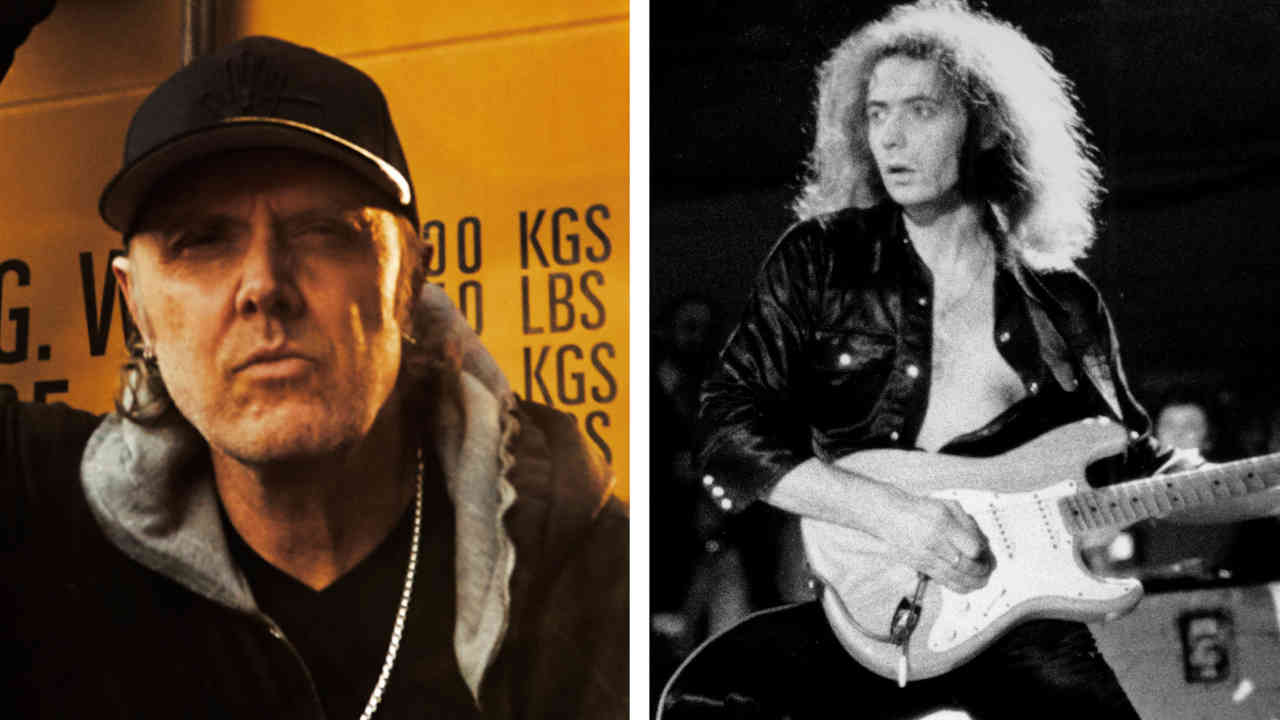

The brand new issue of Classic Rock magazine features Deep Purple on the cover – something which doubtless makes Metallica drummer and Purple uber-fan Lars Ulrich very happy. Back in 2012, Metallica contributed a version of When A Blind Man Cries to Re-Machined: A Tribute Deep Purple’s Machine Head, an all-star covers album dedicated to Purple’s classic 1972 album Machine Head. At the time, Lars sat down with Classic Rock to talk about his lifelong love of Ritchie Blackmore and co.

You wrote a beautiful eulogy to Jon Lord [late Deep Purple keyboard player, who died in 2012] on the Metallica website. You were obviously a friend of his as well as a fan…

He wasn’t just another keyboard player on the side of the stage. In 1966 and 1967, when Jimi Hendrix, Pete Townshend and Ritchie Blackmore were taking the electric guitar to a new level by using banks of Marshall stacks to beef up their sound, Jon Lord was one of the first guys in hard rock to take the keyboards through the same process.

What was so different about his sound?

He took a fairly standard instrument like a Hammond organ, put it through amplifiers and Leslie cabinets and introduced a whole new way of forcing the sound out of the keyboards. Ritchie Blackmore said the other day that Jon formed Deep Purple. He was certainly the instigator that made things happen. If not the musical leader, Jon was the spiritual leader of the band. He was a pioneer and I think that somehow that’s got lost in the last few weeks. People are talking about, obviously, what a gentleman and a fantastic band member he was, but he really did something nobody had done before with keyboards.

How did you end up getting to see Deep Purple when you were just nine years old?

There was a tennis tournament at the KB Hallen [in Copenhagen] that started on a Monday morning and Deep Purple played there the night before. For some reason they invited all the tennis players to come down to the concert. My dad [Torben Ulrich, former professional tennis player] invited me along. It was spring 1973 and Purple were promoting Who Do We Think We Are. I remember Ritchie Blackmore throwing his guitar up into the lighting rig, rubbing it against the speaker cabinets and playing it with his ass. Jon Lord was waving the beast around, Ian Gillan was hidden behind a curtain of hair playing the bongos, Roger Glover was holding the beat down, while Ian Paice was sitting back there with his specs on doing his thing. I had never seen anything like it before. I was completely and utterly blown away. As you can imagine, it was the loudest, coolest thing I’d ever seen.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Was your dad a Deep Purple fan?

He was into Cream, Hendrix and The Doors, but when I played him some of their stuff he certainly appreciated it.

What kind of music were you into at the time?

I liked Slade, The Sweet, Status Quo. But Deep Purple were a whole different thing. They had a heaviness, energy and power. In my musical vocabulary, they were the extreme.

Why do you think Deep Purple were so popular in Europe?

Led Zeppelin never registered on the same level when I was growing up [in Denmark]. Zeppelin somehow seemed to be more of an American thing. There was also a perceived image of them. Ritchie Blackmore was very visual, but he wasn’t posing in a way like Robert Plant with his open shirt, sweaty chest and ‘I’m a God, come back to the hotel room and blow me’ attitude.

Why did you pick When A Blind Man Cries? Is it true that you originally wanted to cover it for 1987’s Garage Days Re-Revisited EP?

No. Back then it was about the riffs and the energy of the music. I think increasingly as we’ve gone along, the covers have become more about what James could kill vocally. I always believed that James could sing a beautiful version of When A Blind Man Cries. So when we were asked to do this project it was a no-brainer.

Are there other songs you would like to cover?

Quite a few. Soldier Of Fortune and The Gypsy from the Stormbringer album, and Sail Away from Burn, which has one of the best Ritchie Blackmore riffs ever.

Did you cover any Purple songs with Metallica in the early days?

No we didn’t, but we would jam on their stuff a lot in our rehearsals, songs like Black Night and Highway Star, we did them all the time and also some Rainbow songs like Stargazer and Tarot Woman. It’s really where our musical roots lie.

Let’s run through the tracks on Machine Head, starting off with Highway Star…

It’s one of the greatest opening tracks of all time. The way it fades up with Blackmore chugging away on the down pick, it’s one of the first songs to feature that kind of style, along with Hard Lovin’ Man from Deep Purple In Rock. Jon Lord takes the first solo, followed by Ritchie. It’s got four verses, which is quite unorthodox. And that solo Blackmore plays with a continuous melody. He also did that on Burn, and it became his trademark.

Maybe I’m A Leo and Pictures Of Home?

Maybe I’m A Leo has got a great riff and bluesy feel and some introspective lyrics from Gillan. Pictures Of Home starts off with a great drum roll and there’s Gillan talking about being on top of a mountain and you’re instantly transported there. You’re thinking, ‘Where is he? Is he up on the Alps where they recorded the album?’ Ian is a really great storyteller.

Never Before?

That was Purple’s first attempt at a commercial single, which is interesting as the Machine Head album has fuckin’ Smoke On The Water on it.

Which brings us to Smoke On The Water…

You really don’t need a guy in Metallica to tell you it’s one of the greatest rock songs of all time and certainly the definitive hard rock riff. I don’t play guitar and I can play it, my kids don’t play guitar, they can play it, the three guys walking past me down the street right this minute, who don’t even know who Deep Purple are, can more than probably play it.

Lazy?

This is the bluesy side of Deep Purple gone really heavy. It is instantly recognisable. It is blues, but it is also quintessential Blackmore. Also, Ian Gillan gets out his mouth organ, as he calls it, and plays on it which is great.

Space Truckin’?

What’s cool about Space Truckin’ is that there’s no guitar in the opening riff. It’s just keyboards and bass. Again, Ian Gillan goes for very visual lyrics about tripping around in space. Deep Purple are known for being an anti-drug band and this is the closest they come to an acid trip. You really feel like you’re on a rocket ship with that drumbeat in double time. Paice is playing so fast, that track along with Speed King is one of the bridges to speed metal.

The production was essentially down to Glover and Paice…

With Blackmore, Gillan and Jon out there fighting for pole position, having Roger and Ian doing the production was probably the smartest way of doing it. It also made sure that the drums weren’t lost in the mix. On a lot of albums in the 70s, the drums were just buried in the background.

What’s your overview of the Mark III line-up?

Burn feels like a very heavy Ritchie Blackmore record, whereas Stormbringer with Glenn Hughes’ influence was a little more R&B. It’s a different band. Gillan was always out front doing stuff. If he wasn’t singing, he was playing bongos. Songs like Space Truckin’ were Ian Gillan’s cue to get the whole audience to clap along, he was an active frontman. With David Coverdale, when he came in, you could feel that he was young and more than just the singer. You could say that the Deep Purple peak years were 1972 and 1974. In 1973 you hear in the live recordings and see in the videos that Ian Gillan has already mentally checked out and in 1975 you can see that Ritchie’s mentally checked out.

Have you ever investigated the Mark I line-up?

Emmaretta [1969 single] and Wring That Neck [from 1968’s The Book Of Taliesyn] are heavy but it doesn’t sound like they’ve quite found their footing yet.

Which is your favourite Purple line-up?

That’s like asking which one of your kids you like the best. I can’t answer that. To me they’re almost like different bands. You could say that the Mark II line-up was edgier, harder. Mark III was more soulful and, vocally, with two singers, stronger.

Who are the other fans of Deep Purple in the band?

You have to fight with Kirk [Hammett, Metallica guitarist] on who’s the biggest Ritchie Blackmore fan. I’m pretty sure I have him beat, but he may tell you otherwise.

Have you always followed their career?

Of course! When they re-formed in 1985, we were on the Ride The Lightning tour, playing clubs in America with WASP and Armored Saint, and Hetfield and me flew down to St Louis to see them. After our tour was over we followed them around. Girlschool were supporting so we shacked up with them. We finally got the honour of playing with Purple in ’87 at the Monsters Of Rock festival in Germany. Having Metallica and Deep Purple on the same gig poster wasa big deal for me.

Did the re-formed Deep Purple Mark II still feel relevant to you in 1985?

It was different. I don’t know if it had the same magic, but Perfect Strangers is a great record. It was cool to see them back together. I got a chance to spend time with Ian Paice, which was my dream come true. To me the interplay between Ian Paice and Ritchie Blackmore is otherworldly. If you listen to live versions of songs like Child In Time, it’s unbelievable what goes on between the two of them. And then to have Roger Glover hold down the fort with the bass. But Ian Paice is the unsung hero of that band. People talk so much about Bill Ward, John Bonham, and Ian Paice is just not given credit with his role in shaping this musical dynasty.

Did you connect with any other members?

I played football with Ritchie. Steve Harris was there too. I was like a kid in a candy store.

How was Ritchie?

He was aloof, he was arrogant, he was Ritchie Blackmore. You wouldn’t want him to be any different. I remember the first time I met him was backstage in Sacramento in 1987, on the House Of Blue Light tour. An assistant introduced us and I said, “Hey how are you?” And he looked at me, took a pause and said, “If I said that I’m fine that would be such a conventional answer.” That was the first thing he said to me. I was like, “Dude, you are the coolest person on the planet.”

What about Ian Gillan?

He is one of the nicest people on the planet. We’ve had some great sessions, one that involved him coming to my place to watch some Purple footage. That was surreal. I felt like I was 16 again, pretty much how I always feel when I’m around Deep Purple.

Which Metallica song would you like to hear Deep Purple play?

I’ll tell you what would be fucking cool to hear – Deep Purple play Orion. Or maybe a song like Welcome Home (Sanitarium) because it’s got a ballady thing going on, with a little bit of heaviness and guitar.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents A Tribute To Deep Purple. The brand new issue of Classic Rock, featuring Deep Purple on the cover, is onsale now. Order it online and have it delivered straight to your door

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.