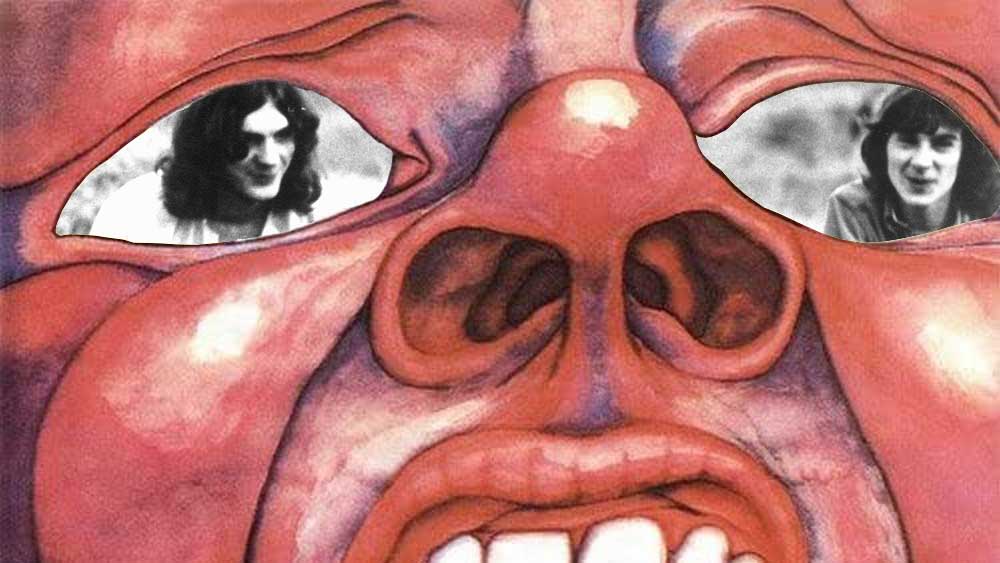

"I knew I had to say something, and that I didn't have many words to say it in": a track-by-track guide to King Crimson's In The Court Of The Crimson King

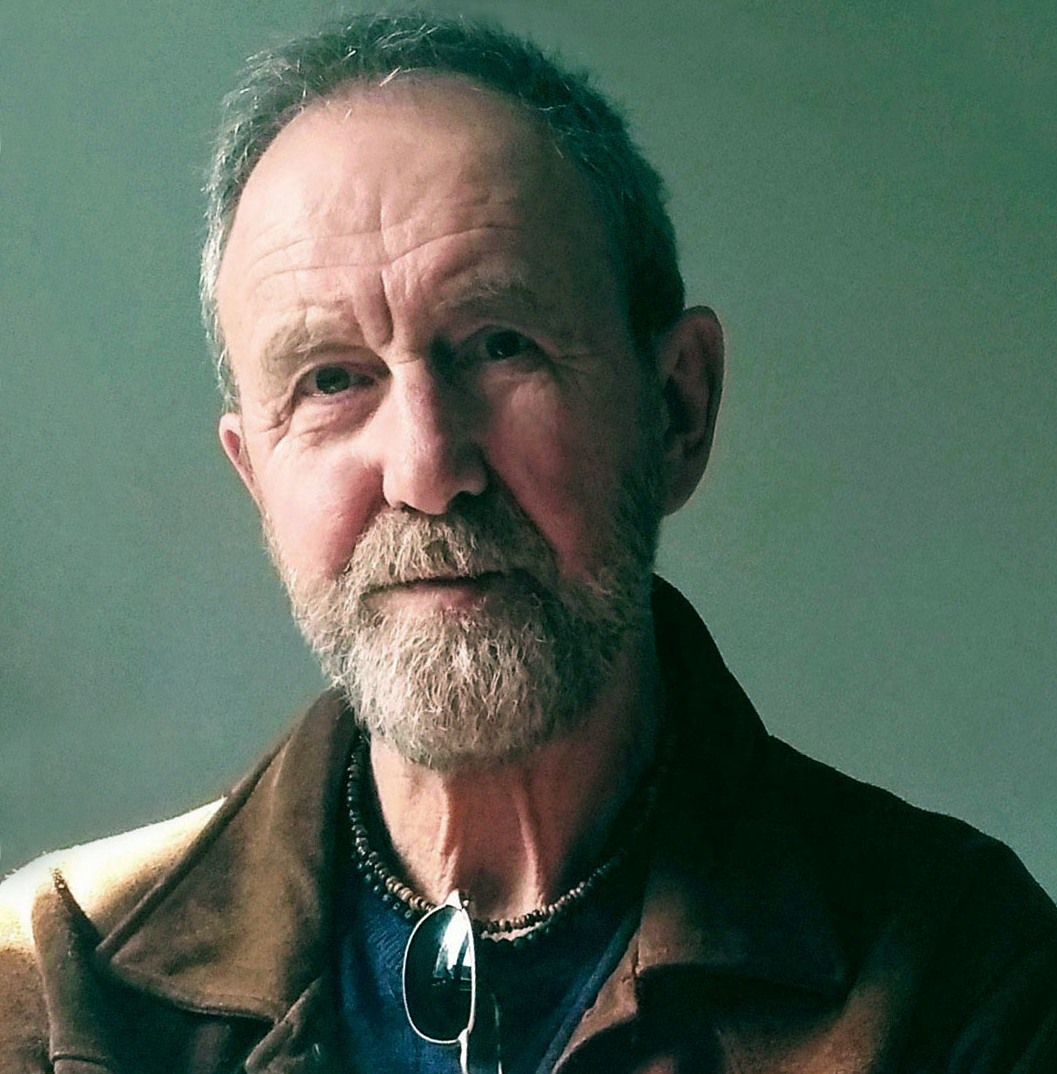

Original King Crimson members Ian McDonald and Peter Sinfield on the creation of key tracks from the first true progressive rock album

In mid-July 1969 a new British band called King Crimson, just signed to Island Records, began recording their debut album, just weeks after playing their first official gig on April 9 and days after supporting The Rolling Stones in front of a crowd of half a million in Hyde Park on July 5.

A mere 15 days later they had finished recording a remarkable, ground-breaking album that was sweepingly original, musicianly, creative, expansive; a true rock classic that many people consider to be the first true progressive rock album. When it was released, The Who’s Pete Townshend called King Crimson’s In The Court Of The Crimson King: An Observation By King Crimson (to give it its full title) “an uncanny masterpiece”. And it was.

Below, original band members Ian McDonald and Peter Sinfield take us through the album, track by track.

21st Century Schizoid Man

Ian McDonald: “The first track on the album was the last one we actually recorded. And I’m very fond of letting people know that we actually recorded it from beginning to end in one take, with no edits. We did overdub some parts later. Contrary to what you might think, it was actually a breeze compared to other tracks. The sax solo just ends abruptly, but we needed the tape track to punch in for one of Robert’s guitar parts.”

Peter Sinfield: “The lyrics for …Schizoid Man were written right at the end, where we knew the thing was angry, against the Vietnam war; an angry, modern song of its time. I knew I had to say something, and that I didn’t have many words to say it in. I remember writing the lyrics in the park near the cemetery in Fulham Palace Road.”

I Talk To The Wind

McDonald: “The second track we recorded. My original demo was a little bit more up-tempo and had some guitar strumming, but we changed the arrangement once we got into the studio. One thing I’m pleased with is that I managed to pull out a pretty nice flute solo at the end, under relative pressure. I actually did two and we put them together. You can hear where it goes from one to the other, but that didn’t bother me.

Sinfield: “It’s got some beautiful guitar sounds by Robert – very tricky. Mike’s little pings like water dropping on the cymbals. The vocals are lovely. It was everything it should be. I knew at the time that that track was special, because it was just so moving to listen to.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Epitaph

Sinfield: “Epitaph was a poem that I’d written when I had my own band. It started with the words, and then it was very much a piece of ensemble writing. Ian would come up with an idea, then someone else. I think Greg came up with the idea: ‘But I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying’, which is very Greg-ish.

McDonald: “For some reason, getting that track right eluded us. Epitaph took about 10 hours to put the basic track down down – I made a point of noting that down in my diary. But I think it was worth it because, to me, that’s one of the best tracks on the album, if not the best.

Moonchild

McDonald: “We’d run out of material. And we didn’t want to put a cover tune on our first album. So we were left with gap; we needed another seven to nine minutes. So once we’d recorded the basic track [the front section, with the vocals], Mike, Robert and I went back into the studio, set the tape rolling and just improvised for about 10 minutes. And I think it’s alright.

Sinfield: “Greg really doesn’t play on Moonchild. That sort of free-form improvisation was never Greg’s bag. He was: ‘What’s all this twiddling about? Oh, I suppose I’ll have to put a bass note here.’ He just said: ‘I’m not playing on that.’

The Court Of The Crimson King

The lush-textured, panoramic, epic title track that closes the album was actually the first track the band recorded, on July 16. Hearing this huge, gothic, densely orchestrated piece, it’s almost impossible to believe that it was originally “a sort of Bob Dylan song, if you can imagine that”, says Sinfield. “Ian took it and rewrote the music. He’d studied harmony, he’d studied orchestration, so his references were not just The Beatles, but also big, sweeping things like Stravinsky, Mahler, things that were emotional. And that would come out. That track did take quite a while to pull together.

“I was sort of worried about the vocals. They recorded line by line and dropped in. I probably shouldn’t say that, but there you go."

Classic Rock’s production editor for the past 22 years, ‘resting’ bass player Paul has been writing for magazines and newspapers, mainly about music, since the mid-80s, contributing to titles including Q, The Times, Music Week, Prog, Billboard, Metal Hammer, Kerrang! and International Musician. He has also written questions for several BBC TV quiz shows. Of the many people he’s interviewed, his favourite interviewee is former Led Zep manager Peter Grant. If you ever want to talk the night away about Ginger Baker, in particular the sound of his drums (“That fourteen-inch Leedy snare, man!”, etc, etc), he’s your man.