"Fuelled by booze and pills, they cut their teeth delivering approximations of Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran." Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson on why the early Beatles were so dangerous

As a young teen, Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson fell in love with the mop-top Beatles. But then he dug deeper and discovered something darker, druggier and way more dangerous

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Like most people my age outside of Liverpool, I had no real inkling of The Beatles until Love Me Do, by which time they had, to some degree, been sanitised by their traditionally showbiz-minded manager, Brian Epstein. No doubt he thought it necessary to help the band get gigs, to get a record deal, and those first few hits were what you might call pretty songs. From Me To You, I Want To Hold Your Hand; it was all very innocent.

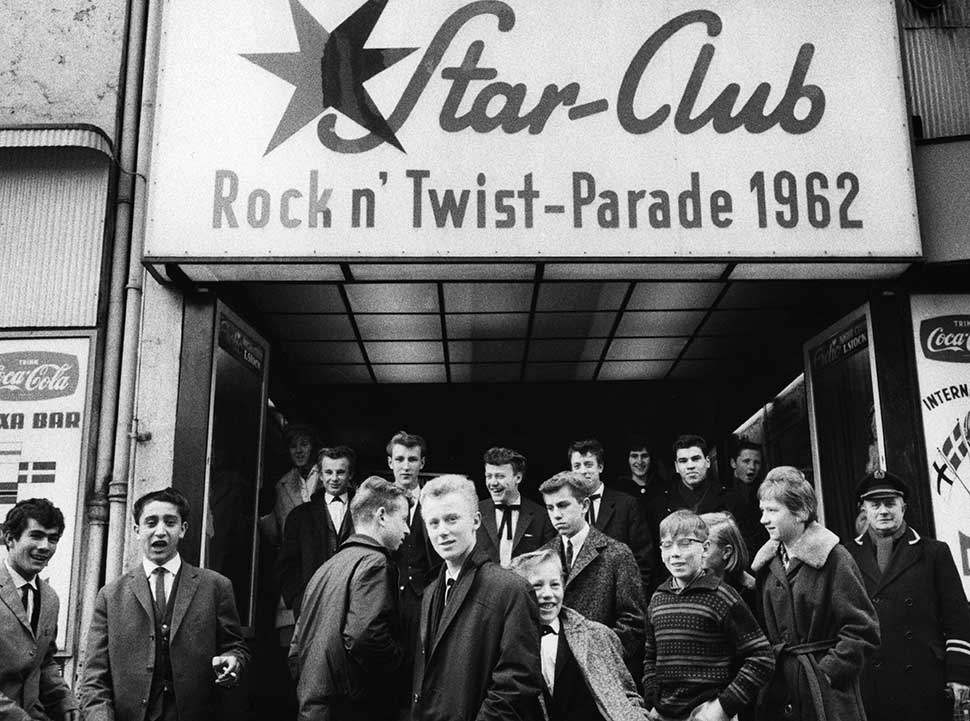

As their fame grew, however, and the back story of their earliest days became more widely known, we cottoned on that this wasn’t how they started. We learned about the Cavern Club, and then we learned about their excursions to the seedy nightspots of Germany [in the early 60s]. With hindsight, you could say Hamburg was The Beatles’ punk period, their edgy and dangerous days that were hard to square away with the almost chocolate-box pop proposition they became.

When I was a schoolboy, I was always attracted to John Lennon above the others, by a long way. Paul McCartney seemed to be the cheerful, cherubic, slightly wet character in the line-up, as if the band had had a Cliff Richard transplant. But John had an attitude, a sense of disdain when it came to being groomed and made to dress in matching suits.

The first time I saw pictures of The Beatles in Hamburg, it struck me that here was Lennon in his natural habitat; leather-clad, greasy of quiff and with an air of menace. Photographs of that period are arguably more iconic than almost any subsequent images of the band.

Hamburg was a rude awakening for many English musicians, a dark place full of aggressive sailors, shifty characters and prostitutes. But in many ways, The Beatles were primed for it, coming from a seaport themselves. These weren’t young boys from leafy Surrey, and Lennon in particular, you expect, was already familiar with the wrong side of the tracks in Liverpool.

He would have felt perfectly at home among the dinginess and squalor. In terms of what they faced at the likes of the Star Club or the Kaiserkeller, Lennon, at least, you’d think, was more than able to handle himself, and perhaps act as a protector of the others, the very young George Harrison in particular. It was a rough environment where they feasibly were met with resistance, so like the punks of the following decade, they had to be brash and confrontational.

That brashness clearly manifested itself in the music they were playing. Fuelled by booze and pills to keep them awake during sets that went on well into the early hours, they cut their teeth delivering approximations of Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran, the moody bad boys whose records they would have bought a few short years earlier. Let’s not forget, however, that it wasn’t just Lennon leading the charge here; Hamburg is where McCartney honed the Little Richard howl he would continue to pull out of a drawer every so often throughout the band’s career.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The part Stuart Sutcliffe played in those fledgling days is a matter for debate, as while his creative contribution to the band’s music was minimal, his presence was helpful to the others. John, in particular, was close to Stuart, and having him around may well have given him more confidence to find himself, for his own character to evolve.

In terms of influencing others, the perception of The Beatles as bad boys in Hamburg is a bit of a misnomer – Lennon was probably the only one who’d be handy in a fight. The Rolling Stones were initially seen as ruffians, but that wasn’t so much an attempt to emulate the grubbiness of the formative Fab Four as it was a calculated reaction to their mop-top image. Mick Jagger always looked too self-conscious to be considered a tough guy; he looked like he’d fall over if you blew on him.

Having their time in Hamburg as part of their biography worked well for The Beatles. It was interesting that they had that pedigree of being a bit vulgar, and not just fresh-faced youths who bowed to the Queen at Royal Variety Performances. You had to somehow prove your mettle if you were going to have credibility, and Lennon took that on into future aspects of his career, the bad-biker clone ultimately replaced by what was perceived by many as a mad, dangerous hippie. He never lost that element of dissent.

You could argue that McCartney worked the hardest to distance himself from the prickliness of the Hamburg days to become a more wholesome performer, while Lennon strived to hold on to his venom. That combination was what always appealed to me, though; the velvet glove covering the iron fist is what made The Beatles work so well.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 202, published in September 2014.

Best known as the frontman and flautist with progressive rock legends Jethro Tull, with whom he's released 24 studio albums, including the classics Aqualung (1971) and Thick as a Brick (1972). Anderson has also released six solo albums under his own name, and worked with everyone from Fairport Convention to Men Without Hats, Steeleye Span to Opeth.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.