“When asked about his family, Jim would often explain that his parents – still very much alive – were dead”: How The Doors’ Jim Morrison went from from drunken teen rebel to leather-clad 60s rock god

Drunkenness, arrests, ambition – Jim Morrison’s wayward childhood paved the way for the future

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

“Take off your clothes!” the singer leers at the thousands of fans surging toward him on the stage. “Let’s see a little skin around here! Let’s get naked!”

It’s March 1, 1969, and Jim Morrison is in full rock god mode onstage at Miami’s Dinner Key Auditorium. Blitzed out of his mind from a day of drinking, The Doors frontman has spent much of the show provoking the crowd. Many are unimpressed by his antics, though not as unimpressed as the Miami cops in attendance. Their mood isn’t improved when Morrison grabs the hat of one of them and hurls it into the audience.

Then comes the fateful moment. “Do you want to see my cock?” he howls. Reports differ as to whether he actually gets the organ in question out or not, but it’s a signal for fans – some of them naked – to rush the stage, causing it to buckle under the additional weight. “We’re not leaving until everyone gets their rocks off!” Morrison cries above the chaos, his provocation fulfilled.

They finish the gig, but four days later, six warrants are issued for Morrison on obscenity charges. Soon afterwards, he gives himself up to the FBI in Los Angeles.

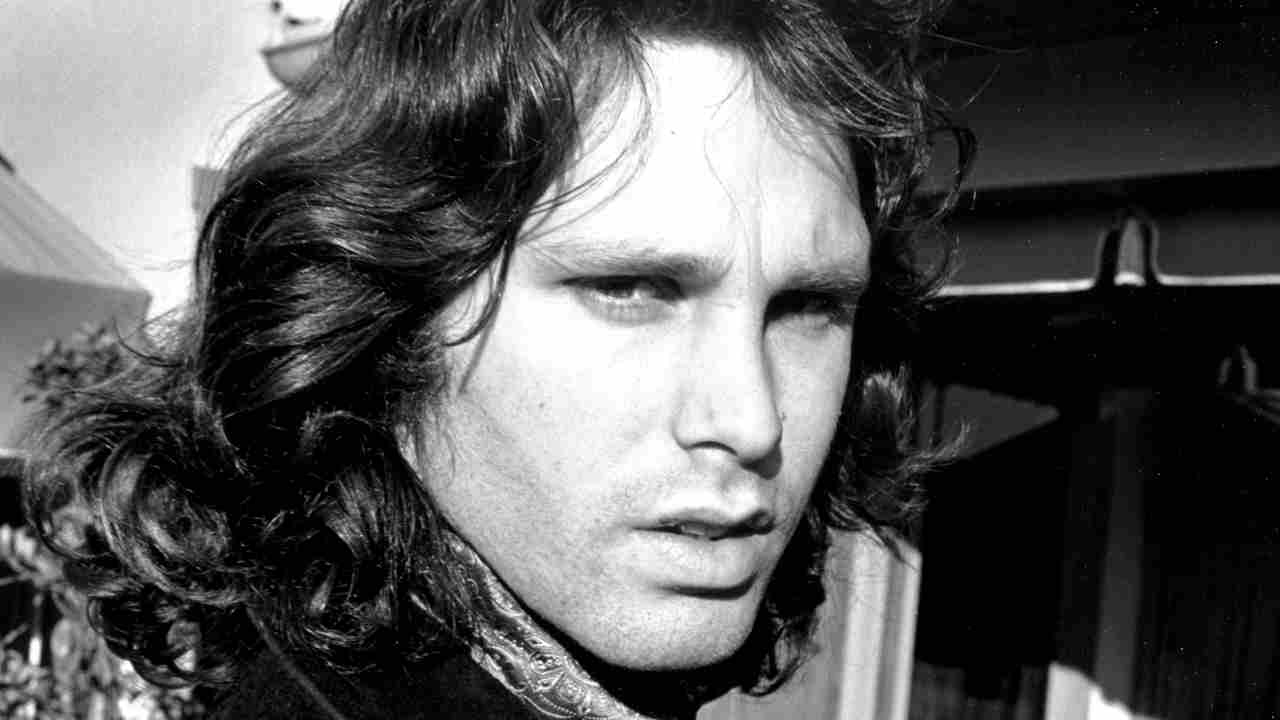

The incident in Miami has become a key part in the myth of Jim Morrison. Yet perception of the singer as Lizard King – the carefully-curated persona that cast him as both shaman and poet, the primal, sexualised spearhead of a new revolution – demands more than a superficial glance at his notorious rock’n’roll exploits. To truly understand the transformation, one must dig deep into the seething cauldron of his formative years, a period characterised by isolation, erudition, grandiose delusions and a peculiar brand of artistic self-absorption that would lay the groundwork for one of music’s most magnetic figures.

Jim Morrison was born on December 8, 1943, in Melbourne, Florida, 200 miles up the Atlantic coast from the location of the riotous scenes he would provoke nearly 26 years later. The son of Admiral George Stephen Morrison and Clara Clarke Morrison, he was called ‘Jimmy’ by friends and family and would remain so throughout his youth.

A pivotal moment in Morrison’s early years has become a cornerstone of his mythos. In several interviews, he claimed that, while driving with his family and grandparents one morning, they came across a fatal accident involving a group of Native Americans who had been killed in a truck crash. He liked to say that as they drove past the wreck, the soul of one of the victims passed into Jim’s body, infusing him with centuries of wisdom and power. Though just three or four years old at the time, Morrison cited this incident as a revelation that unveiled the mysteries of mortality. In his autobiography, Riders On The Storm, sceptical Doors drummer John Densmore describes the tale as “a leap of faith if there ever was one.” True or not, the story embodied Morrison’s quest for higher consciousness and his propensity for vivid myth-making.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

His upbringing was defined by physical and emotional upheaval as his father was shuttled from one military posting to another across the country. Jim’s early years were a parade of new faces and changing scenery, a relentless motion that must have bred a profound sense of restlessness. This life of constant flux and displacement was bound to leave a mark, and it transformed young Jimmy into a tempestuous adolescent.

It was after the Morrison family relocated to Claremont, California that his rebellion first flashed brightly. By sixth grade, he was a model student and an athletic standout, but underneath the surface was a simmering cauldron of defiance. The seeds of his iconoclasm were evident when he was expelled from the Cub Scouts for disruptive behaviour and for disrespecting his den mother – a prelude to the more public spectacles that would define his later years.

He bullied his younger siblings, often to shocking lengths. In 1955, during a family ski trip, Morrison’s reckless behaviour nearly ended in tragedy when he piloted a toboggan also containing his two younger siblings straight toward a barn, impervious to his sibling’s cries and mother’s screams as he careened toward impending disaster. His father’s intervention averted potential catastrophe, but the young Jimmy’s dismissive attitude towards the incident hinted at a burgeoning contempt for authority and a thirst for chaos.

As Eisenhower-era conformity began to clash with the rebellious surge of rock’n’roll, Morrison’s restless spirit found itself at odds with the stifling expectations of his upbringing. By 1958, his family were living in Alameda, California, 10 miles east of San Francisco. The 15-year-old Jim often skipped school to frequent San Francisco’s beatnik circles, entranced by the radical ideas of Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs. He hung out at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s bohemian City Lights bookstore, where he mingled with the city’s artistic avant garde and became enmeshed in the Beat ethos. His intellectual appetite was voracious, consuming the works of Burroughs, Friedrich Nietzsche and Norman Mailer with an insatiable thirst.

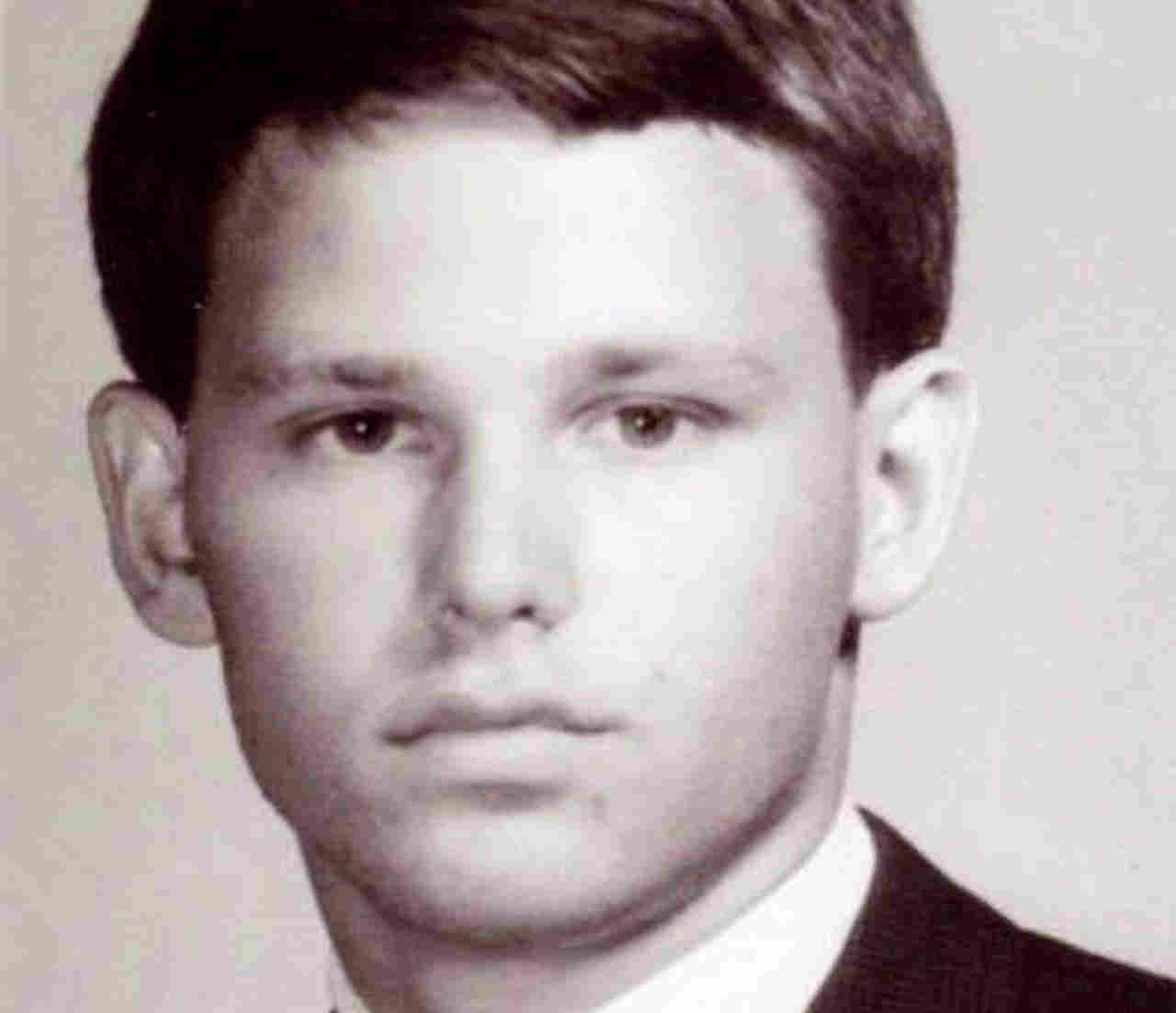

He also developed a deep fascination with art house films and the intellectual dimensions of postmodern filmmaking. n 1958, the Morrisons moved once more, Alexandria, Virginia, where Jim finished high school with a growing sense of isolation and disillusionment. His final years at high school were marked by a descent into a darker, more withdrawn demeanour. He leaned into a beatnik style that complemented his nihilistic outlook, spending hours haunting the city’s waterfront and immersing himself in books that further alienated him from mainstream society.

His rebellious streak was now paired with a self-destructive edge, and his proclivities for manipulation and abuse became increasingly frequent. His girlfriends bore the brunt of Morrison’s petty cruelties and withering emotional slights. In eleventh grade, he once rode a bus into Washington with his then-girlfriend, suddenly ditching her and disappearing into the city, leaving her alone in hysterics.

After graduating in 1961, Morrison – by most estimations, the smartest kid in his class – had few options, having elected to not submit any college applications. When his family moved to San Diego for the Admiral’s next assignment, Jim was not invited. Instead, he ended up back in Florida, attending St. Petersburg Junior College and eventually transferring to the racially segregated Florida State University in 1962.

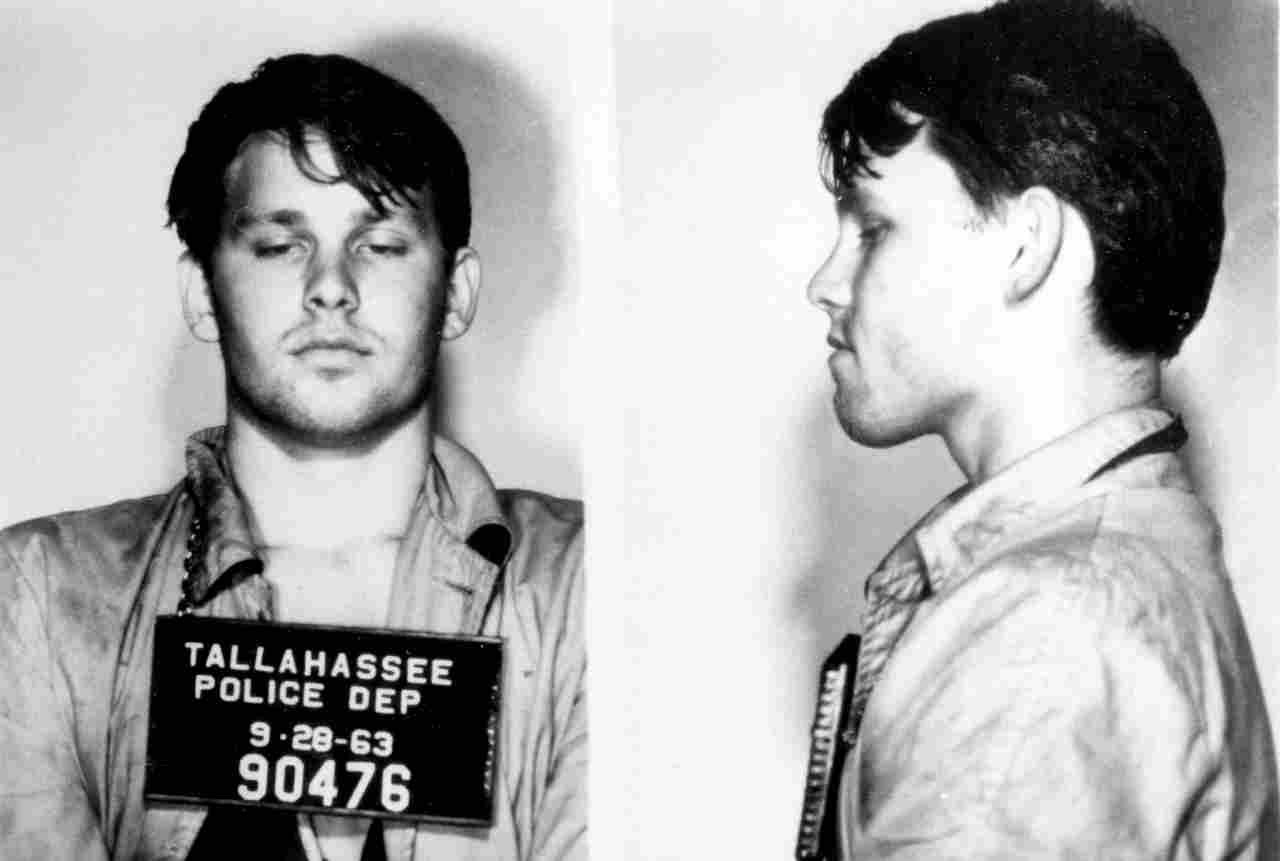

There fascination with literature and film grew, but FSU’s lack of a film program was a problem. Morrison’s dreams of filmmaking and poetic glory were stifled by the beer-swilling, football-centric culture of the university. In September 1963, at the age of 19, he was arrested at a school football game when, incensed by what he estimated was the sub-par performance of his classmates on the field, his drunken heckling turned to stealing a police officer’s helmet, drawing a list of charges including public drunkenness and resisting arrest. The charges were later dropped.

It was a disillusioning period for Morrison, but it set the stage for his next big move. When a professor suggested he apply to UCLA’s Theater Arts Department in Los Angeles, which had a film school, the die was cast. In 1964, he headed west once more. This wasn’t merely a geographic shift – it was a leap into the heart of artistic experimentation and intellectual rebellion.

At UCLA, Morrison’s enrolmed in Jack Hirschman’s class on Antonin Artaud, the French playwright and theorist renowned for his radical and surrealist approach to theatre. It endowed his artistic sensibilities with a fresh, darkly poetic dynamism. Artaud’s theories on ‘Theatre Of Cruelty’, with its emphasis on breaking down traditional forms and exploring the raw, visceral aspects of human experience, resonated deeply with Morrison’s burgeoning creative vision. It laid a solid foundation for his future endeavours, both on stage and off.

Imbued with the freedom to fully commit to his intellectual pursuits, Jim cut ties with most members of his family, citing a lack of empathy and support. When asked about his family, Jim would often explain that his parents – still very much alive – were dead. It’s a lie that persisted through their self-titled debut album, which included press materials that identified Jim as an orphan. It seemed essential to Jim’s persona that he shun all trappings of normalcy or anything that gave the impression Jim was just like everybody else. A normal childhood, stable family and even the occasional loan from his parents just didn’t play into the myth.

For Jim, UCLA was a period not marked by stellar academic achievement but by an immersion into a world where he could mould his burgeoning ideas about art and existence into something tangible. He grew out his hair and embraced acid and pot. His final diploma, earned in 1965, was merely a footnote in a broader narrative of creative upheaval and artistic exploration. Those years were less about acquiring a degree and more about absorbing and manipulating the radical ideas of his professors. He began to channel his creative energies into film and poetry. The avant garde spirit of Los Angeles, combined with the libertine and increasingly psychedelic cultural scene, offered him the perfect backdrop for his artistic pursuits.

He’d long been a fan of Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and the blazing pioneers of the rock movement of the 50s and early 60s, but nowhere in any reliable account of Morrison’s youth does one find any passion for becoming a musician, let alone a rock star. His musical aspirations were secondary to his broader artistic ambitions, and his eventual foray into rock stardom was as much a serendipitous detour as a planned trajectory.

The first step of this detour occurred on a sun-baked stretch of Venice Beach in the July 1965. As Jim wandered along the sand, he ran into his UCLA film school buddy, Ray Manzarek – a fellow auteur who also played keyboard in Rick And The Ravens. Sitting in the sand, they talked about life, school and of course, girls, before Jim revealed that he’d been writing songs. Prodded by Ray, the uncharacteristically self-conscious Jim reluctantly sang the lyrics to Moonlight Drive, a song that would eventually appear on The Doors’ second album, Strange Days.

It was a revelation. As Morrison ran through one song after another, Manzarek began envisioning their band. Famously, the latter proclaimed to Jim, “We’re gonna make a million dollars.” According to Manzarek, Jim replied, “Ray, that’s exactly what I had in mind.”

In that moment, the seeds of The Doors were sown. This fateful encounter was more than a casual meeting; it was the ignition of a creative inferno that would set the world ablaze. Morrison and Manzarek stood at the precipice of something far greater than either could have fathomed.

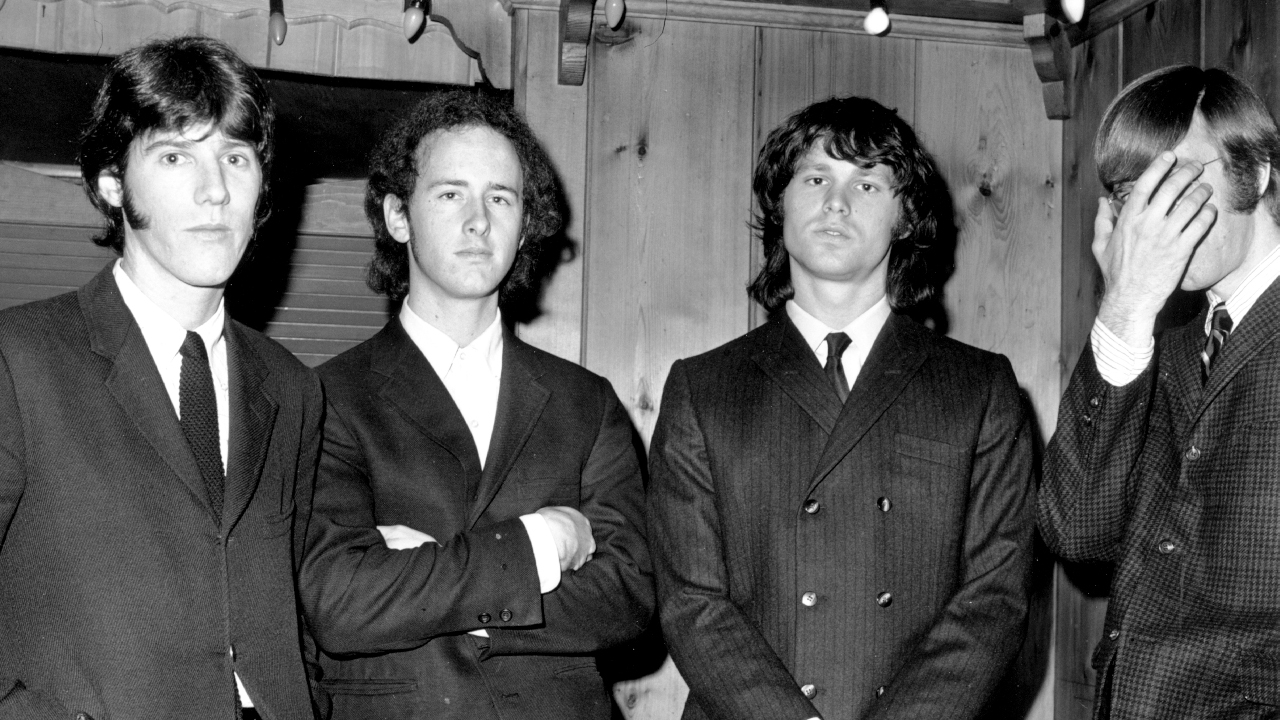

By the start of 1966, the Doors’ line-up had coalesced into the one that would carry it through the next five years: Morrison and Manzarek, plus guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore. They secured a residence at Sunset Strip club London Fog, before making the leap to the more prestigious Whisky A Go Go.

It was at the Whisky that Jac Holzman, the owner of rising independent label Elektra Records, came to see The Doors play for the first time. Unimpressed, he left midway through the set but, at the insistence of friends, he returned the next night, and the next and the next. On August 20, 1966, Elektra offered the band a deal. Five months later, in January 1967, The Doors released their self-titled debut album.

That album would mark the beginning of new chapter in the life of Jim Morrison, the wayward kid with the volatile personality, grandiose vision and artistic brilliance. The Lizard King was about to emerge from the chaos of his past, ready to confront the world with a blend of poetic darkness and rock’n’roll audacity that would define an era. The future was about to be rewritten in the hallucinatory haze of The Doors’ debut album – a journey that began with a troubled youth and culminated in a mythic legend.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents The Story Of The Doors

Hailing from San Diego, California, Joe Daly is an award-winning music journalist with over thirty years experience. Since 2010, Joe has been a regular contributor for Metal Hammer, penning cover features, news stories, album reviews and other content. Joe also writes for Classic Rock, Bass Player, Men’s Health and Outburn magazines. He has served as Music Editor for several online outlets and he has been a contributor for SPIN, the BBC and a frequent guest on several podcasts. When he’s not serenading his neighbours with black metal, Joe enjoys playing hockey, beating on his bass and fawning over his dogs.