Fleetwood Mac's Jeremy Spencer: the true story of the man who went missing

Was Fleetwood Mac guitarist Jeremy Spencer really kidnapped mid-tour by a religious cult who shaved his head, brainwashed him and hid him from the band?

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

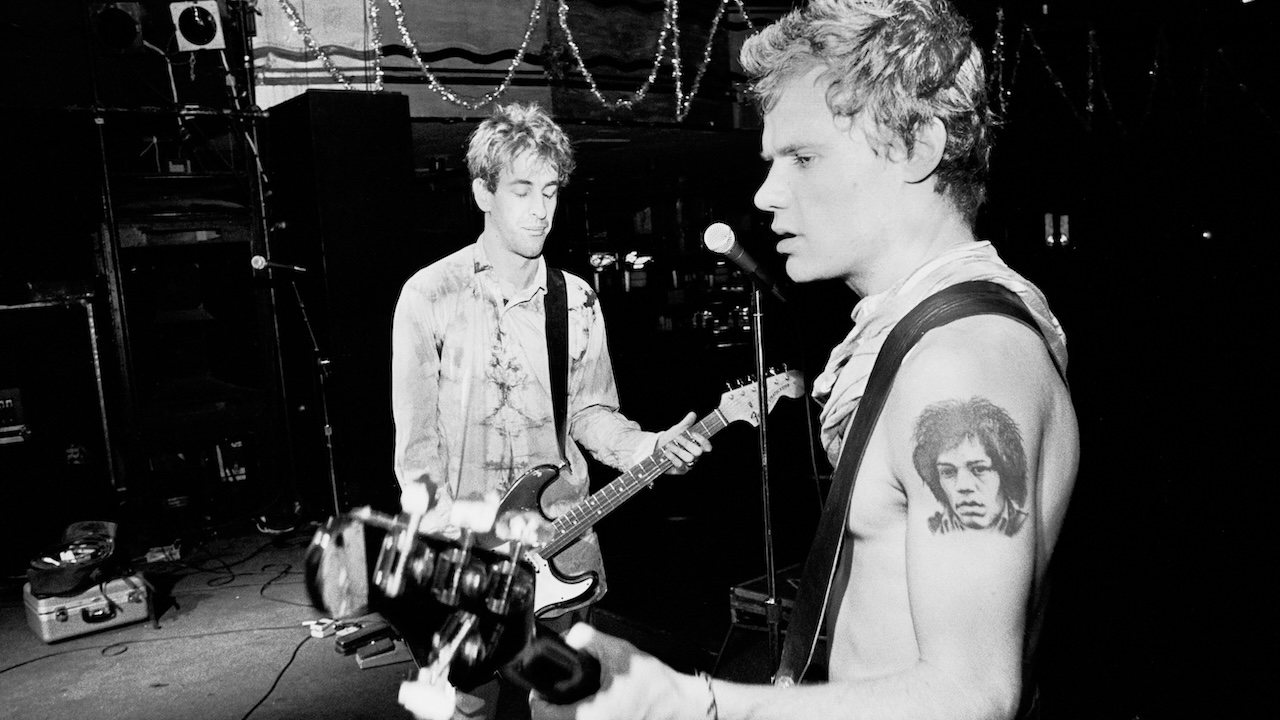

It’s late February, 1971. A headline in UK music paper Sounds reads: ‘Jeremy Spencer “Lost in America?”’. The NME also reports that early on in Fleetwood Mac’s lengthy tour their slide guitarist suddenly went missing in LA. The paper then ratchets up the story with hearsay that he’s joined ‘a strange religious cult’, is ‘walking around in a daze like a zombie’ and ‘just mumbles “Jesus loves you”’. Apparently, ‘he’s with about 500 of these people and they’re just like vegetables’.

That ‘religious zombie’ story, it now turns out, is like the one about onetime Mac mainman Peter Green flipping out and threatening his accountant with gun unless he takes back a fat royalty cheque: both are fabulous Fleetwood Mac myths, and too juicy to be upstaged by what really happened.

Many years later Mick Fleetwood tells a reporter: “His [Spencer’s] head was shaved and he had a different name. Basically, he was like a zombie.” Even the band’s drummer has apparently been sold on the myth.

Thirty-five years after his ‘mysterious disappearance’, Jeremy Spencer laughs at the old tales – more in exasperation – and is happy to set the record straight. But he’s wary of journalists, and with good reason: “It’s the misrepresentation… They just insist on putting in those things. I guess that’s journalism,” he says, quizzically.

These days the ex-Geordie (born in Hartlepool, brought up in Lichfield in Staffordshire) blues wonder is minus the corkscrew hair and plus a mid-Atlantic accent. Now in his mid-50s, a boyish, slightly mischievous smile sometimes punctuates what he has to tell you. And clearly he enjoys a laugh.

“The way I left [Fleetwood Mac] was wrong and a mistake,” he now readily admits. “I should’ve told them right away, but I was desperate. The night before I left, we were all in Mick’s [Fleetwood] hotel room. He was very distraught, listening to this live recording of the band before Peter left. When my Stranger Blues Elmore James thing came on I just blurted out: ‘This sounds like shit.’ I went to my room and just prayed to God to somehow get me out of this. Also, they were getting into cocaine. To me that was a Stones-type drug, and the feeling of invincibility that it gave you just seemed wrong to me.”

Myth has it that the day he walked out of Fleetwood Mac, Spencer went to a bookshop and on the way was ‘whisked off’ by a religious cult called the Children of God who promptly shaved his head, changed his name to Jonathan, brainwashed him and hid him from the band.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The reality, Spencer emphasises, is that any secrecy at the time was not sinister; it was because the Children of God didn’t want a high-profile, George Harrison/Hare Krishna-style media circus. Spencer was invited to visit the C of G’s building by a busker he’d met in the street; he was not abducted by a religious press gang. There was no coercion; rather he had to reassure them that he was sure about joining. He had his hair cut – not shaved – because Fleetwood Mac were due to head down to the redneck, no-long-haireds territory of Thurber, Texas.

Guitarist/vocalist Peter Green was flown in to rejoin his old band temporarily so that the band could continue the US tour. Later, American guitarist Bob Welch was brought in as Spencer’s permanent replacement.

But some bleak, character-building years lay ahead for Fleetwood Mac before a restyled, remodelled version of the one-time raw blues group recorded their 1977 blockbuster album, Rumours.

“I knew of their hard and often hellish struggles,” Spencer says, “and I prayed that God would give them more success than they ever had with Peter and me. God certainly answered those prayers.”

Asked what his happiest memory of his time in Fleetwood Mac is, Spencer says: “I guess… being asked to join by Peter. I was chuffed. We had some fun times. But then it became not such a happy thing. After first hearing me play, Pete said: ‘Right, you’ll do Elmore James and I’ll do BB King and that’s how it will be.’”

Green thought Spencer played slide guitar with “conviction”, but Spencer now says that increasingly he felt undeveloped and uninspired as he saw the musicianship of his bandmates progress.

Before music and blues mapped out his early 20s, it was Spencer’s artistic talent that had shone through. As a 12-year-old at grammar school, he was invited to attend art classes at Camberwell Art College where the average age of students – sometimes drawing naked models – was closer to 20.

His father was an RSPCA inspector and an accomplished pianist. Jeremy took piano lessons, but then lost interest once he heard Cliff Richard, Marty Wilde and the exciting, burgeoning new sound of the 1950s, rock’n’roll.

It was while attending Stafford Art College that Spencer first heard bluesman Elmore James, while listening to a blues compilation album at a friend’s house. He was mesmerised the moment he first heard James’s steely electric slide playing. He began to learn slide guitar. Fate helped him along when he broke a leg, and he spent the entire six weeks of convalescence absorbing and learning to imitate James’s style. It became an obsession.

That summer – 1967, the Summer of Love – a young Mick Fleetwood’s carefree piss-artistry got him sacked from John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Then Peter Green left Mayall to put together his own band, and invited Fleetwood on board as his drummer. Then came Spencer’s successful audition in Birmingham. Green named his band Fleetwood Mac, after a tune he’d written and recorded with Fleetwood and bassist John McVie. Another Mayall band member, McVie eventually joined Fleetwood Mac in September, Bob Brunning having deputised at the group’s first few gigs.

Some wild nights were in store with these protopunks: early Mac gigs often meant filthy language on stage, and even the occasional condom full of milk being chucked from the stage.

By this time Spencer was, as they say, a nice bunch of guys: the guy who read the Bible back at the hotel was also the guy who got the group banned from London’s Marquee club for walking on stage with a dildo poking out from his undone flies. But, laddish larks aside, Fleetwood Mac’s take on the blues soon made some of its elder statesmen, such as BB King, sit up and listen.

Spencer also had real talent on stage for mimicking Elvis, Mayall and others. And whereas most other bands’ between-numbers banter was predictable, Spencer often came up with the bizarrely unpredictable.

A year later, 18-year-old guitarist Danny Kirwan joined as the group’s third guitarist, mainly as a musical foil for Green. Spencer’s Elmore and Elvis impersonations became like a band within a band, and mostly he sat in the wings when Green and Kirwan played their material – “I’d be sat there until it was my turn, and I’d walk on thinking, ‘Uuuhhh… this is like going to a job’” – although his dissatisfaction certainly didn’t show.

In 1969 Fleetwood Mac were the undisputed kings of white-boy blues. They also notched up three UK Top 5 singles that year – Albatross, Man Of The World and Oh Well – none of which were strictly blues.

Then in May 1970 Green suddenly quit his band and the music business, guilt-ridden by the big money his songwriting earned him – and with his judgment clouded by the after-effects of taking LSD. He’d wanted Fleetwood Mac to play more free-form jams rather than rigid songs, and for some of the band’s earnings to go to charity. They didn’t. So he left.

Although at first unsure of what to do, Spencer and Kirwan eventually fronted the band and wrote some fine material together.

Ex-Chicken Shack pianist Christine Perfect (who later married bassist McVie) joined soon after Fleetwood Mac recorded their fourth album, Kiln House. Six months later Spencer did his mid-tour ‘disappearing act’ in LA.

In mid-1972 Kirwan was sacked, at just 22 years old a stressed-out victim of music-biz-induced alcoholism. There then followed an unsettled period for Fleetwood Mac, with a number of line-up and stylistic changes (amid a soap opera of break-ups and internal affairs) as the group struggled to find an identity. When they eventually did, it wasn’t long before they gave birth to a monster – 1977’s global hit, Rumours.

Meanwhile, after leaving the group Jeremy and his wife Fiona spent time bonding with the Children of God. He soon formed a C of G band, which played free concerts in places like New York’s Central Park.

Evangelising through music also naturally followed. In 1972 CBS bankrolled Jeremy Spencer And The Children – a rushed and lacklustre album, he feels. But making the record did give his guitar playing the crucial inspiration that had eluded him during his time with Mac.

During the Rumours era, a then-rookie American journalist (who Spencer now refers to as Carrion Crow) contacted him while researching a feature he was writing about Fleetwood Mac. The two men met at a London hotel, and over dinner Jeremy explained about his chosen new life. But in the published article, no mention whatsoever was made of this meeting; instead it told only of a dazed, derelict-looking Spencer spotted on the streets of London handing out religious pamphlets.

Still, the mega-success of Rumours also created commercial interest in ex-Fleetwood Mac renegades. In the late 1970s Warners offered Peter Green a $1m deal, but at the last minute he backed off. Capitol had signed guitarist Bob Welch (who quit Mac in ’74). And Atlantic Records chief Ahmet Ertegun was put in touch with Spencer and his band for what became 1979’s Flee album.

“They started by telling us our ideas were really great… everything was fine,” Spencer says of Atlantic, with much laughter. “Next thing, we’re being told to listen to a pile of two-bit funk albums as a reference point. Despite what they’d said, what they wanted was late-70s disco-funk. Then our girl singer is dropped from the sessions and a set of rhythm slaves and a flash-Harry guitarist get hired. It ended up with just me, our keyboardist and this New York Italian old-school vocal coach.

“In the studio, this vocal arranger could tell I was down about the way things were going, and he said to me: ‘It’s hamburgers!’ I said: ‘What do you mean? I don’t understand.’ He then said: ‘You wanna know how I reconcile with this? It’s just hamburgers. Look, I hate this shit as much as you do, but then I tell myself: “Just give ’em hamburgers – it doesn’t matter. Just give ’em the shit they want and don’t worry about it!”’

“Anyway, we saved three of our songs from their treatment – Flee, Cool Breeze and Travellin’ – but on the others they got their way. The album sold badly, and Atlantic dropped us.”

It was in the Philippines in 1986 that, through his work, Jeremy met his current partner, a German lady called Julie who has travelled the world with him ever since (he has eight children by his ex-wife Fiona). The couple remain devoted to The Family (as the Children of God became known in 1978) and work for its publishing arm: Jeremy is a brush-and-ink comic book illustrator and also writes stories. They currently live in Ireland, and their life with the organisation has taken them across the world, to Japan, Brazil, India, Mexico, Sri Lanka and Switzerland – a man of the world, you could say.

In the 1990s Spencer did several charity gigs in India for the blind, and in August 2005 he appeared – to critical acclaim – at Norway’s Notodden Blues Festival. There he also did a guest spot with gospel/soul legend Solomon Burke, who then invited him to take part in a gospel concert in Amsterdam.

A huge change in Spencer’s approach to playing slide guitar happened in the mid-1990s, when he stopped using a plectrum and began playing with his fingers – a style he had long admired in the playing of blues legends Albert King and Albert Collins.

Nowadays he practises daily for his own pleasure, writes witty songs, and his playing now visits many more musical worlds than the polished Elmore James pastiche that brought him fame, if not fortune, in Fleetwood Mac. Proof of his eclecticism lies just around the corner, with the release this year of a recently filmed live-in-studio DVD, and a CD due to be recorded in Norway. Doubters: prepare to be amazed.

But his Fleetwood Mac days still “haunt” him (as he puts it) when press interviews end with the inevitable question: will there ever be an original Mac reunion?

“Mick Fleetwood was hot on the idea a couple of years ago,” he explains, perhaps surprisingly. “But since then they’ve had that hit with the Say You Will album, so they’re busy I guess. And for me, I don’t relish or really need what will come with a reunion – you know, the publicity and hype.

“I already have a full-time job I enjoy,” he concludes, “so if I do anything with music I want it to be small and selective, and not the big draw. The proposed CD to be recorded in Norway will be called Precious Little – and that’s just how I want it to stay.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 90, in 2006. Precious Little was released the same year, and another 12 solo albums have followed. In February 2020, Spencer was the surprise guest when Mick Fleetwood & Friends played a tribute show to Peter Green at London's Palladium Theatre.

Martin Celmins is a musician, journalist and writer. His books include Peter Green: Founder of Fleetwood Mac, the authorised biography of British blues artist Duster Bennett, Jumping at Shadows, and the official illustrated History of Orange Amplification. He has written extensive liner notes for Peter Green and Fleetwood Mac CDs, and has contributed features to national press titles including The Sunday Telegraph.