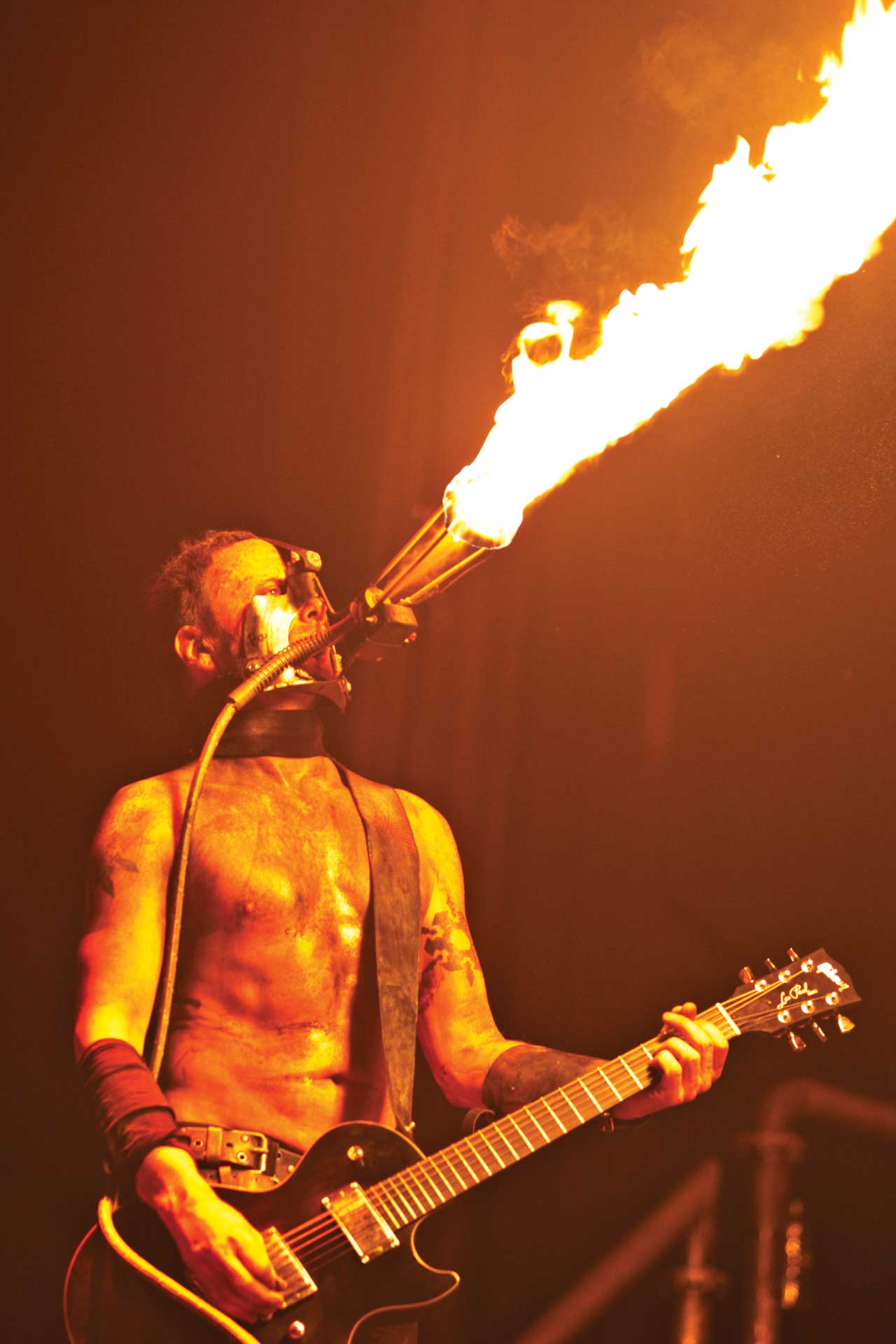

Fireworks, flames and giant uteruses: Behind the scenes of Rammstein's epic live shows

Rammstein have the biggest show in metal, it’s as simple as that. We got the people behind the scenes to reveal how it all comes together

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

By their second-ever tour, supporting Swedish rap-metallers Clawfinger in Europe, Rammstein already had a reputation as a hot new band.

“They had pyros, flamethrowers and in Austria, they actually set the lighting rig on fire,” singer Zak Tell recalls of the shows, during November 1995 and January 1996.

“Thankfully, nothing was destroyed. But even back then, there was no doubt Rammstein were into putting on a big show. The only difference between now and then was that the budget was a lot smaller. However, that didn’t hold them back.”

They were dedicated performers who knew how to hype up an audience. “I was fascinated by the fact that they had foam mattresses put down on the stage, and that was so they could hurl microphones around theatrically, as if they were deliberately breaking them,” says Zak.

“But the reality was there were these mattresses laid out to cushion the impact. That was a clever move. Rammstein knew what they were doing and how to create an illusion.”

But on September 27, 1996, during the band’s ‘100 Years Of Rammstein’ concert at Arena Berlin, a beam loaded with fireworks fell down, injuring five people.

The band subsequently enlisted Nicolai Sabottka as their production manager, who moved into creating SFX as managing director of his Berlin-based special effects team, FFP.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

He’s completed courses at Dresden’s school of explosives, and has licences for stage-close proximity pyro, aerial displays, manufacturing of pyrotechnics, SFX for movies and TV, as well as extensive training on flame effect devices.

“My job is to work on new FX and search the market for anything exciting,” he told Metal Hammer in 2015. “If we can’t find what we want, we have a team of engineers who work on special effects and an entire pyrotechnics factory in the state of Montana who will build what we’re looking for.”

Subsequent shows saw Till using a bow that sprayed fireworks and wearing a robe streaked with flame, as they continued to tour Europe and break the US. But they really ramped up their offering in 2001, graduating from theatre-sized venues to arenas in some European territories following the release of their third album, Mutter.

They hired Lighting and Production Designer LeRoy Bennett, known for his work with Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson, who conceived a giant uterus for the opening of the show. With the lights down and the audience screaming, Flake Lorenz would play the eerie 5/4 as the large, red, pulsating organ descended from the ceiling.

Then each bandmember apart from Till would slither out and fall onto the stage wearing nothing but a nappy, staggering around in confusion before a doctor escorted them to their instrument to take up the song.

“They were totally into it,” he laughs today. “The birthing canal they were coming out of was a tube that was used for escaping out of a fire, and it had fireproof webbing on the inside that zig-zagged through it. Normally you’d have clothes on while going down it, but because they were coming through in diapers, their skin would get web-burned, so we had to cut the tube short so they could slide out easier.”

LeRoy was inspired by the biomechanical style of late Swiss artist H.R. Giger, along with Mutter’s cover photo, a foetus in a jar photographed by Daniel & Geo Fuchs for their 2000 book, Conserving. “The band gave me the book and it had that kind of eerie, East Germany hospital feel to it – weird, very dark laboratory experiments and things like that,” he says. “But at the same time, it’s finding beauty in ugliness and freakiness.”

he design process for a Rammstein show starts a year beforehand, and while the set changes for every cycle, they always have a distinctive look. There are the bright, surgical spotlights, glinting off Giger-esque metal structures. The sense of a retro-futuristic industrial hell, with its bandmembers as the workers who keep the machines going.

“What I’ve tried to establish is a live branding that is consistent in some way, even though we’re advancing all the time, because their music has a very defined feel to it,” explains LeRoy. “The idea is that everything is very rigid, very bold, with very big, strong, clean lines. There’s moving lights, but they don’t move like they would for other bands, where there’s a lot of movement; they’re there so I can reposition them at a different angle.

"Everything is like an army. Everything is old and rusty, much like an abandoned East German power plant. So any time we get set-pieces in or there’s a new stage, everything gets treated and painted so it looks like it’s been around for 40 or 50 years, neglected.”

It’s the same with the costumes. Designer Sophie Onillon says they texture up the fabric prior to each show. “They have a table with a lot of boxes, like ashes and artificial blood, and before they go onstage they put it on their costumes and their skin,” she explains.

That visceral approach sits alongside the mechanical setting, a dynamic that’s explored in the way the band move onstage. LeRoy says that guitarist Paul Landers is the “leading creative person” when it comes to stage design, building models and making drawings of suggestions that often defy physics.

“He’s totally into manual – guys pulling stuff,” explains LeRoy. “It’s about the theatricality of the whole performance. So it means that if doing something is maybe cost-prohibitive in a more sophisticated, automated way, if it can be done manually and you can see people doing stuff? Cool. So there’s a balance between technology and reality. There is cold, and there is warmth in everything they do.”

You can see this approach in the infamous cooking pot stunt during Mein Teil. Clad in his bloody apron and chef’s hat, face set in grim determination, Till rhythmically manoeuvres Flake’s steely torture chamber to centre-stage before throwing off the lid and sharpening his knife. “It would have been easier to put that thing on some kind of a lift and get it to the stage, but no, it was Till pushing it up the ramp himself,” marvels LeRoy. “That thing is heavy, but Till’s a big guy.”

Till and Flake are the focal point of many onstage antics. Sophie, who also started working with Rammstein in 2001 – she says drummer Christoph Schneider handled costumes before then – has dreamt up some of their wildest outfits. During Ich tu dir weh, when Till puts Flake into a bathtub and pours sparks on him, the keyboardist emerges trembling in an unforgettable sequinned jumpsuit.

“The guys at the beginning, except Till, didn’t really like it,” she reveals. “But then they saw it was a good idea. But for me Flake is different, and he can really wear it with a lot of dignity. He has to be a little light in this dark thing, you know?”

Sophie’s also the mastermind behind Till’s pink, fluffy jacket, which the stentorian frontman wears completely unironically. She came up with the idea after seeing a pink wool carpet in a children’s bedroom.

“I told him, ‘I want to see you in a pink thing!’” she says. “But the guys in the band didn’t know anything until five minutes before he came out for the first rehearsal. Apart from Flake, the rest of them just stood there and said, ‘What is that?!’”

Surprisingly, the costumes don’t get damaged by the pyro – Sophie’s more concerned about using thick thread and hard-wearing materials to prevent deterioration from the immense amounts of sweat produced in the heat.

But there has been the odd ‘happy accident’ – like when Till was wearing his flaming, chainmail trench coat in 2001, and accidentally set his pant leg on fire. According to LeRoy, he was so pleased with the result that he decided to set his entire body on fire during future concerts.

“The whole gag was that he had a Nomex [flame-resistant] suit on and a mask that looked like his face,” explains LeRoy. “He set on fire and Flake comes out with a fire extinguisher full of flammable powder.

And so Till turns into a big ball of fire and eventually he falls down and the crew come out, put him out, and drag him offstage. And there was dead silence. I went back to see Till and he goes, ‘I guess I better get up at the end of that, because I think they thought I died!’”

Like a frenzied opera, Rammstein’s performances intensify over their duration. Their last run of arena shows started with unreleased song Ramm 4 and climaxed with the eye-frying Engel, Till’s flaming wings unfolding like a metal-as-fuck Icarus. Hell knows what they’ve got planned for their next monumental extravaganza.

“We’ve made this kind of world where it starts off very claustrophobic and intimate, and reveals more and more of the stage set as the show goes on, building the dynamics,” LeRoy says proudly. “What I love about those guys is that they have no fear of anything. They make other artists look like pussies.”

Eleanor was promoted to the role of Editor at Metal Hammer magazine after over seven years with the company, having previously served as Deputy Editor and Features Editor. Prior to joining Metal Hammer, El spent three years as Production Editor at Kerrang! and four years as Production Editor and Deputy Editor at Bizarre. She has also written for the likes of Classic Rock, Prog, Rock Sound and Visit London amongst others, and was a regular presenter on the Metal Hammer Podcast.