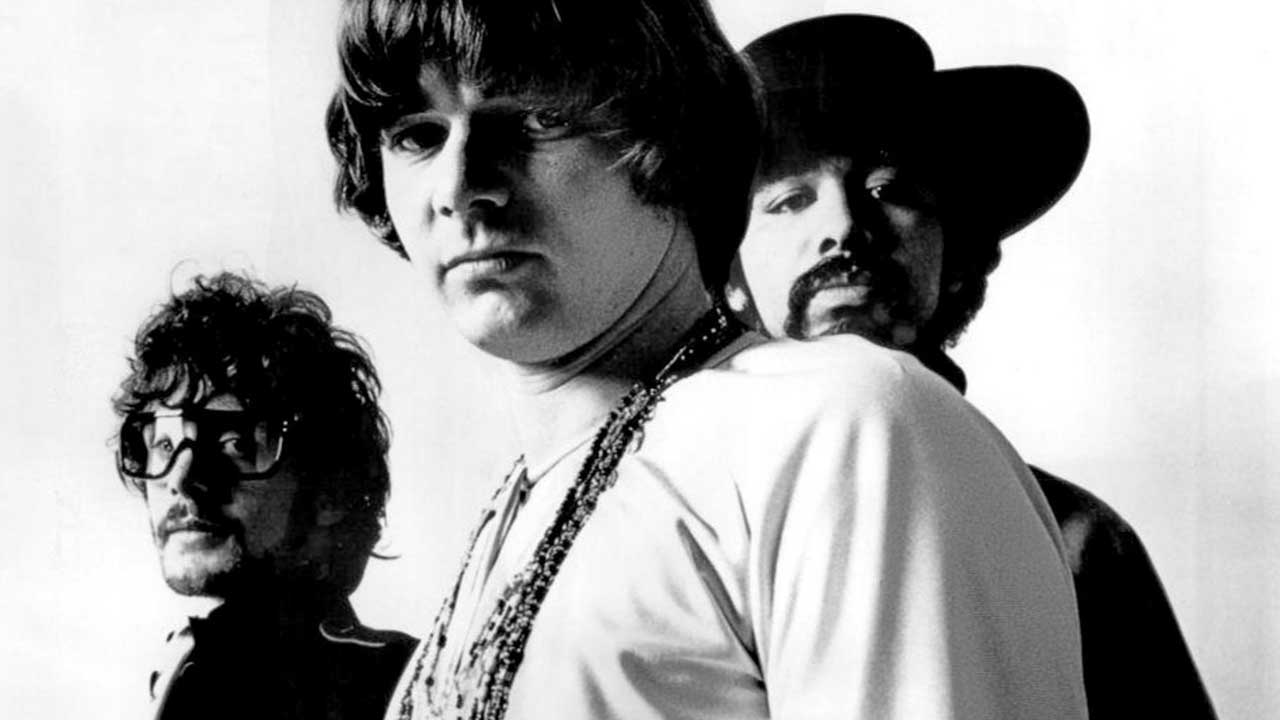

Fired up by riots: how Steve Miller found himself at the heart of a musical revolution

Joker's Wild: Steve Miller's biggest hits may have been radio-friendly, but he was educated by blues and jazz legends and fired up by radicalism

In 1968, Steve Miller was at a crossroads. Aged 25, he’d been a professional musician since he was 12 years old. Brought up in Wisconsin and Texas, one of three brothers in an academic family with staunch socialist leanings, Little Stevie ‘Guitar’ Miller learned his chops literally at the knees of Les Paul and Mary Ford, Lightnin’ Hopkins and T-Bone Walker.

“I was really fortunate because my parents loved music,” Miller says. “My dad loved jazz and blues, and he had a tape recorder right after World War II – one of the first really good professional ones. He offered to record Les Paul. Les and Mary Ford were working at a club in Milwaukee and they became very good friends with my family.

"The next thing you know there’s all these parties going on at the house, and Charles Mingus, Red Norvo, Tal Farlow, Les and Mary Ford are coming around and I’m hearing great music and meeting some really amazing people… and I’m just a little kid.

“I watched Les perform quite a bit and he was so good and funny and made it look so easy. He made anybody think they could play the guitar. Next thing I knew we moved to Texas and I was nine years old and T-Bone Walker came over to the house to play a party. I had stayed home from school sick that day because my parents had rented a piano and I wanted to play it.

"T-Bone came over and played from 6pm to 5am and he and my dad became good friends. He came over again and again. So I have all these memories. And he taught me how to play guitar behind my head and how to play single-note leads.”

It was these formative years that convinced Miller he could make a living as a working musician. Following university in Chicago, he upped sticks to the west. When he arrived in California to join the psychedelic gold rush, his first opinion was: “I am going to clean up here. There were a lot of ‘folk musicians’ who’d seen A Hard Day’s Night and heard the Rolling Stones and wanted to be pop stars, but they couldn’t earn 25 dollars in Texas. They could barely tune their guitars. They were terrible."

"The first time I saw the Grateful Dead I went, ‘Whuh?’ They were a rag-tag buncha folks. Same with Jefferson Airplane. I thought they were pretty lame. I’d already played 2,000 gigs before I got to Frisco. I wasn’t impressed. I liked the Quicksilver Messenger Service guys. Dino Valenti was a good songwriter, though they weren’t a great band. I liked Country Joe & The Fish, who made original music. I hung out with them.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Miller recorded with Barry Goldberg, from The Electric Flag, and played Monterey. He earned his stripes and backed Chuck Berry even before Capitol dangled a contract under his nose. “When the Miller Band backed him at Bill Graham’s request, first thing he said at rehearsal was: ‘Okay, no one take a shave or shower until we’ve played.’ Just before the gig, he disappeared, and returned loaded as a zombie on downers.

"We backed him all over California for two years and he got more and more annoying. At the Carousel Ballroom he got shitty with us on stage. Afterwards he came to my dressing room and I told him: ‘Hey, fuck you, Chuck. Get your own fucking band, get your own fucking amp and get the fuck out of my dressing room.’ He was fine from then on.”

Miller was never really part of the West Coast scene, simply because he was so contrary, but he liked the environment. “I’d taken LSD 25 from the Sandoz lab in Switzerland with a Doctor of Philosophy at University in Madison in 1965. We had books, music and deep discussions. By the time I got to the Monterey Festival, everyone was taking Owsley’s acid and it became trivialised. Let’s put strychnine, speed and cat food in!

"Acid should be taken in the right circumstances. Driving downtown tripping to rough places like the Fillmore West wasn’t a great idea. I stopped in ’68 because drugs and work didn’t mix. I like to be clear-headed and fast on my feet.”

When Miller’s band went into Capitol’s Los Angeles studios in summer of 1968 to record their second album, Sailor, they were firmly established on the West Coast thanks to their debut Children Of The Future, recorded earlier the same year.

“I had been playing with tape recorders all my life, and I couldn’t wait to get into a studio and make records,” says Miller. “The Beatles pretty much were blazing a trail in front of everybody. And Simon And Garfunkel were making albums that were pieces, not just a quick collection of a hit and 11 fast tracks, as a lot of albums were. So we worked hard on it and wanted to improve recording techniques and it was a very creative time in the studio. And the shows too, because it just kept getting bigger and bigger.”

Local interest and great reviews aside, Steve Miller had yet to break out nationally. But it would all change with Living In The USA, the Miller Band’s second single. It sold well enough at the time to crack the Billboard 100 but was reactivated four years later and remains one of the key live songs in Miller’s repertoire to this day.

An apolitical blues with plenty of sting, it demonstrates Miller’s sense of humour and finds his band of the time – Boz Scaggs, Lonnie Turner, Jim Peterman and Tim Davis – at their most playful and powerful.

“The song started out as an anthem for the Democratic Convention in Chicago in ’68, which famously turned into a huge bloody riot,” recalls Miller. “It was a horrible time. There was racial unrest; Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, basic American turmoil. We were playing in Lincoln Park at an anti-war protest festival called Festival Of Life and it was my response to all the political upheaval.”

The Miller Band made their first album with English producer Glyn Johns in London’s Olympic Studios.

“We returned to LA a much better band and we had a more equal relationship with Glyn,” says Steve. “The song was recorded quickly because we’d jammed it up in San Francisco at the Avalon and the Family Dog. My harmonica solos were difficult because Glyn wasn’t used to my blues style, a variation of Little Walter played into the amp with a ton of feedback. He wanted polish, whereas we wanted it rougher, bleeding everywhere and out of control. We won! And that was such a great band at its cusp.

“Sailor was our best record from that time, with me and Boz singing, Tim’s backgrounds and loads of overdubbing and echo. There was no Moog on this track, just lots of straight rock’n’roll and loud B3 organ. I wanted it to sound like Otis Redding – in my head, at least. I wanted it to have some soul power. Studios tend to suck out the energy but we captured the sense of live energy that band was all about.”

While Miller had been politically active at university in Wisconsin, he was still wary of nailing his colours to the mast on record. “When I started, I believed our music would change the world… The thing then was to transcend entertainment and deal with important issues, but the closer I got to people like Jerry Rubin and the Yippie Movement, the less I liked them.

"The further I got into radicalism, the more I realised the people running those things weren’t that great. In fact they became as unpleasant as the people on the extreme right, and for a liberal like me that was bad news.”

Rock music that confronted American plastic values was not new in 1968 – Miller’s buddies Country Joe & The Fish had it down to a fine art while Arthur Lee’s Love turned it into a mission statement – but Miller was wilfully robust.

“I was probably the only writer silly enough to mention dieticians and morticians, but then life was so goofy in America, and still is," he says. "When I wrote the lyrics, though, I thought they sounded a lot deeper because of the global turmoil. On one hand hundreds of thousands were protesting outside the White House, on the other cities were burning, ghettoes were up in flames and elections were being controlled by mobs.

“It was a very dark time. And then there was the draft: the government were running the Vietnam War, and when you’re 18 you don’t really want to die in South East Asia. It was like: you’re 18, you’re next, off you go. You’ve got a one-in-10 chance of dying, so good luck!”

Miller avoided the draft himself by turning up at his army board enrolment in 1965 with a tape of incomprehensible electronic music. “They told me: ‘The Army doesn’t want you, Mr Miller. You will either end up in jail or you will screw up an entire division.’ My work was done. The draft was a death sentence, and yet the funny thing was I knew more about Chinese and Vietnamese relations than the President, who only cared about the financial costs. ‘It’s just 10 cents a year to send you to Vietnam.’ Well, they saved my 10 cents.”

Miller would continue to write and play songs commenting upon the American condition and the everyman.

“I wrote Fly Like An Eagle as a companion piece,” he says. “All about people living on the streets, and the ghettoes in Detroit and Compton, and Indian reservations. I’m trying to raise consciousness and at the same time aiming to pull people in without them knowing. Besides, nothing much has changed since I first scribbled down Living In The USA in some dressing room. We’re still at war and these wars go on and on.

“We did the song with the late great Norton Buffalo on harmonica and it was always a showstopper and I’ve just worked out a new version which we do at all our concerts. We always will. It’s a very important song for me and it has been ever since the day it was released.”

The current leg of the Steve Miller Band's US summer tour kicked off this week. Tickets are on sale now.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.