Rammstein: the making of Liebe Ist Für Alle Da

Porn stars, banned videos, in-fighting, musical differences, it took Rammstein four years to make their Liebe Ist Für Alle Da album, but as the band explain, it's lucky it was ever made at all

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer #198.

It’s 4pm at the Universal Studios office in Berlin and a deathly silence has settled in the boardroom where Rammstein’s comeback video has just been aired for the first time. The song is Pussy, and its video is so explicit that within an hour of seeing it the label have officially cut all ties with it, explaining that ‘the label cannot be seen to have anything to do with it’. Rammstein are back, and in characteristically unsubtle fashion. By now, there’s a good chance you will have heard Pussy, and perhaps even have witnessed its porntastic video. For those who haven’t, it’s fair to say that it’s the raciest promo ever recorded by a metal band, at least one on a major label.

Currently only viewable via a hardcore porn site, the video features the six members of the band engaging in a variety of carnal acts with a collection of attractive ladies, thus providing full-frontal nudity, not only from the professionals involved, but also from the male protagonists, the video culminating in several of the band members (or should we say band’s members) delivering the goods over their co-stars. Whether the group actually ‘performed’ in the video or had their faces attached to male porn actors depends on which of the band you ask, but either way this was a move as risky as it was risqué. It’s one that certainly seems to have paid off, however, the video picking up six and a half million views in its first week of release. And if the video is a bold choice so is the tune itself, an upbeat, disco-esque number, whose tongue- in-cheek lyrics include the ridiculous yet infectious chorus, ‘You’ve got a pussy, I’ve got a dick, so what’s the problem? Let’s do it quick.’

Article continues below

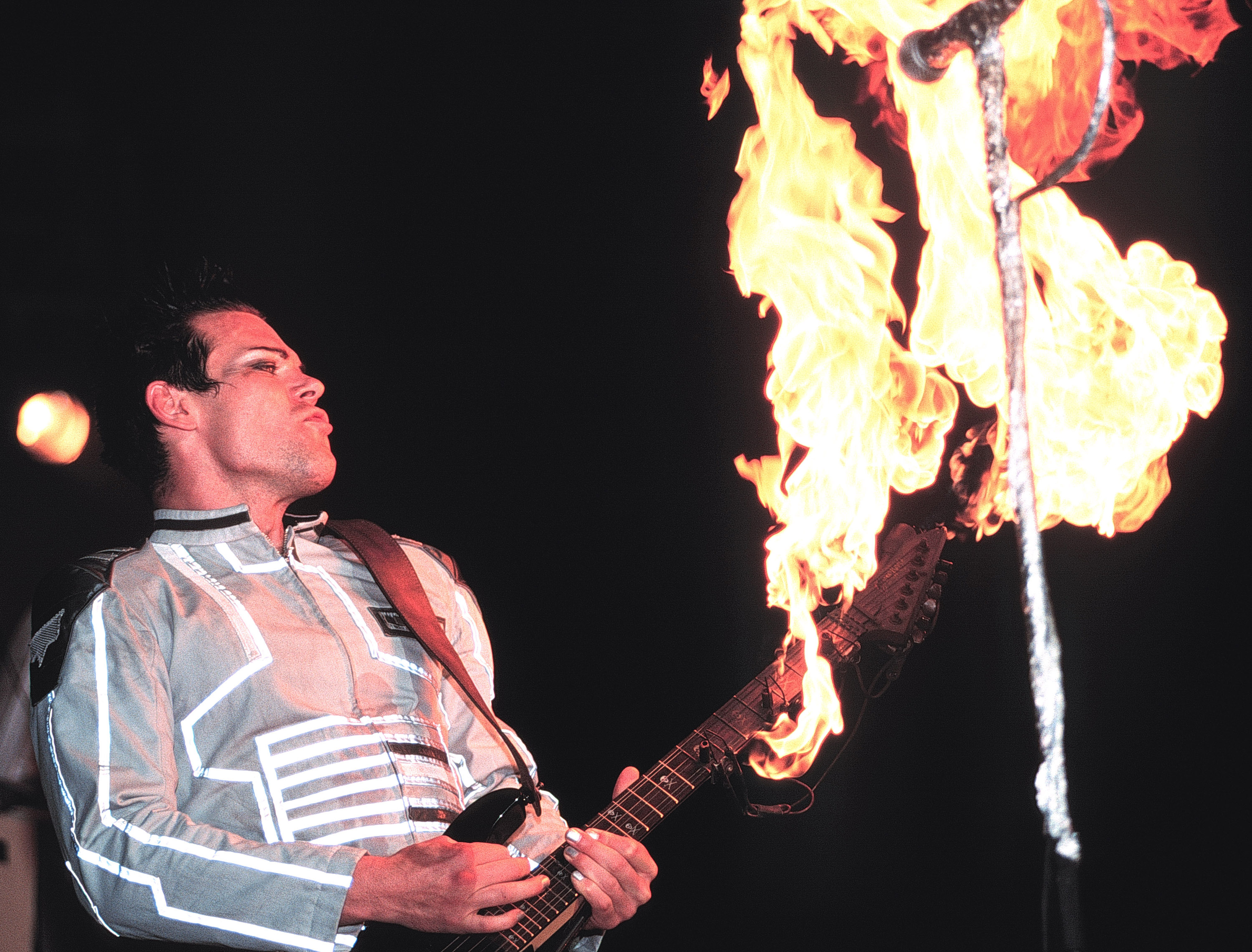

It’s been four years since Rammstein released their fifth album Rosenrot. In that time the group – who have become as famous for excessive pyrotechnics, simulated gay sex, frequent, mistaken accusations of fascist sympathies and unsavoury lyrics (which touch upon such subjects as incest, paedophilia, necrophilia and cannibalism), as they have for their punchy industrial metal – have been largely silent. Not surprisingly this lack of activity, combined with the birth of guitarist Richard Z Kruspe’s new project, Emigrate, in 2005, led many to suspect Rammstein’s untimely demise. And, as it turns out, those rumours almost came true.

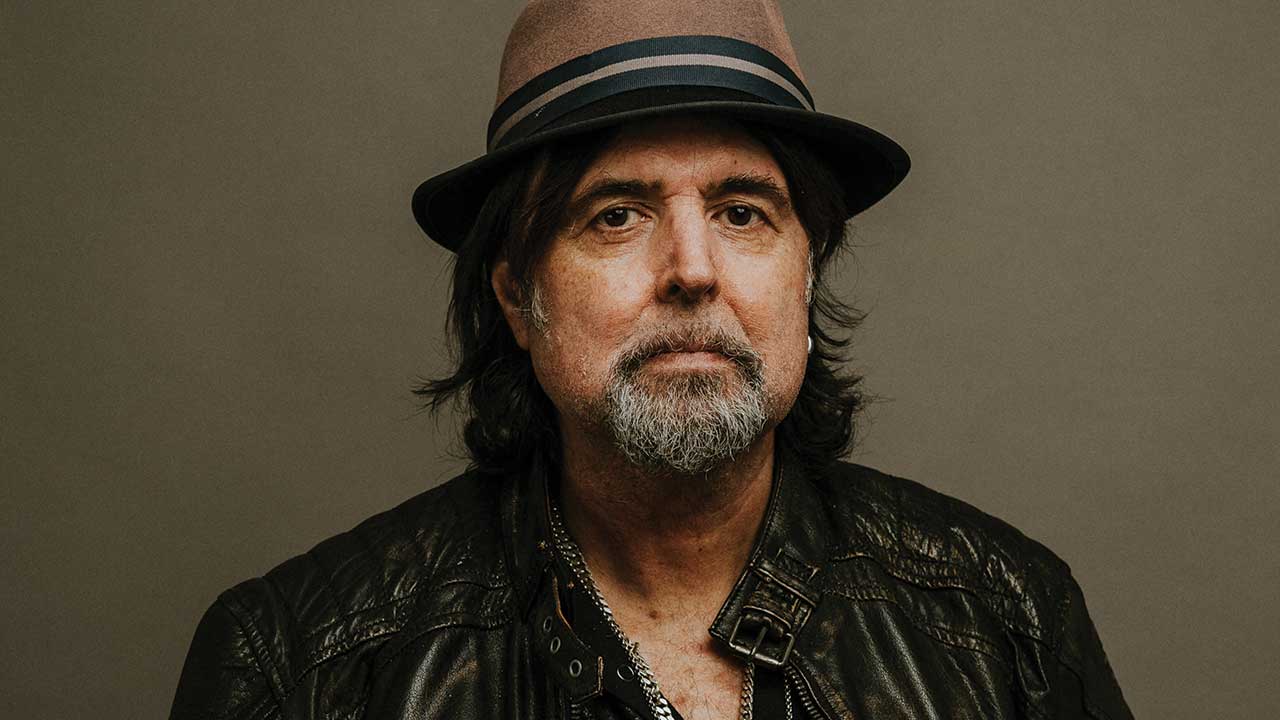

At Universal’s sizable headquarters near to the East Side Gallery, the longest remaining stretch of the Berlin wall, Hammer meets four members of the band: bassist Oliver Riedel, drummer Christoph Schneider, and guitarists Paul H Landers and the aforementioned Richard Z Kruspe. Each of them is holed up in separate rooms – an unusual arrangement and one which points to the unique dynamics of the band – and there is no sign of keyboard player Christian ‘Flake’ Lorenz or vocalist Till Lindemann, who now apparently refuses to give interviews. Of the four present members it is Richard that is by far the most outgoing and talkative – his friendly demeanour offset by the slightly intense, even manic, look in his eye – and it is he who is most responsive when Hammer enquires about the dramatic way the band has chosen to return.

As it turns out the initial idea for the video came from director Jonas Åkerlund, who, as well as playing with Swedish black metal pioneers Bathory in the 80s, has also helped create videos for artists as varied as The Prodigy, Satyricon and Lady Gaga.

“We had a meeting with the label and their approach was to make the first single a ‘core’ single as usual. I felt really bored and felt we should maybe do something else – take this song that didn’t really match the rest of the record and do something darker with it, make it really interesting. So we sent the song to the director and three hours later he sent an email saying, ‘Let’s make a revolution, let’s shoot a porn video.’ And of course we liked the idea.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“People are saying, ‘Oh, it’s cool’, but it will cause a lot of trouble,” he sighs. “That’s what it is: trouble. But that’s the Rammstein way – do something no one would do, but don’t think about the consequences or purpose. That is the energy of the band. If someone comes up with a crazy idea everyone is like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it!’” he laughs. “Nobody in the group would do something like that on their own. I would never come up with an idea to participate in a porn movie, but in a band… they push you into something like that, you can’t say no, you feel maybe it’s going to be good in the end. This video… before I thought it was really good, but now I have a distance. I’m staying in right now, I already had some comments from friends whose kid I’m the godfather of.”

Such differences of outlook are typical in Rammstein. This is far from a traditional band and, indeed, the six musicians apparently have very little in common other than the band itself, which forces them to adopt a democratic process, to the extent that decisions on many issues come down to majority votes. In fact, disagreements as to direction were so dramatic that on the last two albums the six musicians were forced to break off into smaller groups in order to be able to finish songs, which in the end pushed the band into a year-long hiatus.

“This was not Rammstein, you know?” laughs Christoph. “In the early days we always fought about everything and that was sometimes not nice, but in the end we had mostly exciting results. For the first album everybody was involved to the same level, but on the second and third albums [Sehnsucht and Mutter] Richard tried to lead the band, and that reached the point where we couldn’t stand it anymore and we almost broke up. He was trying to control everything, he didn’t want to have anybody change anything that came from his word, and that was a tricky time. Nobody wanted to work like this anymore, so the next album was completely different, he moved to New York and was almost not involved at all. Then on the last two albums we ended up with smaller groups working on songs that were to their taste but not always the taste of the whole band.”

- Lindemann: The Odd Couple

- Rammstein In Amerika: 10 things we learned

- Rammstein: "They Drank And Flagellated Themselves, The Blood's Real."

- Hotei teams up with Rammstein's Richard Kruspe in new video

“There’s a difficulty in retaining a sense of naïvety when writing music now,” explains the towering but quietly spoken bassist Oliver Riedel through his translator. “Sometimes ideas would come up in the morning, and by the time evening rolled around, we had started to critically analyse the music and questions would come up like, ‘Does the world need this song?’ There was so much discussion between the band while making the album that at points we had no idea where to take things and whether the ideas were good or bad.”

“I think it’s always going to be a pain in the ass to work with those guys,” laughs Richard. “There’s always six captains trying to lead the ship and it’s so hard to navigate. It’s very hard to talk about the record ’cos whenever I listen to it I just think about all the fights we had. The beginning was quite easy because everyone was still trying to be polite to each other. The problems started when we had all these ideas. For me it was about getting it finished, I didn’t care what the songs were like, I just wanted to bring it to an end and move on to the next level.”

“We played music every day and gathered ideas, I don’t know how many tapes we filled coming up with the stuff,” explains guitarist Paul Landers, also via an interpreter. “The challenge was to find the good ideas in all the thousands of tapes and this took us a long time and caused difficulties ’cos none of us wanted to throw anything away.”

With the writing process requiring so much energy from the band members, it’s perhaps not surprising that many of them hesitated to return once the official ‘year off’ had come to an end. Richard’s Emigrate project was seen by many on the outside to be a possible block towards the continuation of the band, but as it turns out the project was actually welcomed by the rest of the band, if only as an alternative outlet that might help to cut down the ridiculous number of ideas that were fighting for attention within Rammstein. Ultimately it is trying to turn this huge number of conflicting ideas into songs that presents the biggest ongoing struggle for the group, due to the different tastes and attitudes of the members.

“Songwriting is so energy-sucking for us,” concurs Christoph. “After each album is done, many band members say, ‘I don’t want to do this again like this, something must change’. But then we never do really change. So, for Rammstein, the break was not helpful. For the members it was, as we got a taste of what else life can be beyond touring and albums. But after the break almost everyone wanted to continue the break. They didn’t want to go back and do the hard work that makes an album.”

That hard work at least bore results, in the shape of Liebe Ist Für Alle Da, an album that despite kicking off with a typically anthemic opener, Rammlied, mostly sees the group entering somewhat untypical territory. While closing song Roter Sand (Red Sand) bears a Spaghetti Western vibe, confirmed by Richard who name checks A Fistful Of Dollars director Sergio Leone, for the most part the shift is definitely towards metal, with the symphonic parts sitting aside some undeniably thrashy riffs and precise and pummelling percussion that hints at both early Fear Factory and more extreme metal. The usual epic melancholy so inherent has seemingly been replaced by a more organic spirit of aggression and anger.

“We wanted to do something heavier within the band, and we’d also talked to some fans who said that it was time to ‘turn the screw’ again,” explains Paul, smiling. “So what we did was to take out the redundancies so that you could hear individual instruments better, and the result was that the sound was heavier.”

“We wanted to get back the aggressive energy of early Rammstein, but we didn’t want to get back into this dance metal/industrial style because we don’t have the riffs or ideas anymore,” explains Christoph with typical frankness.

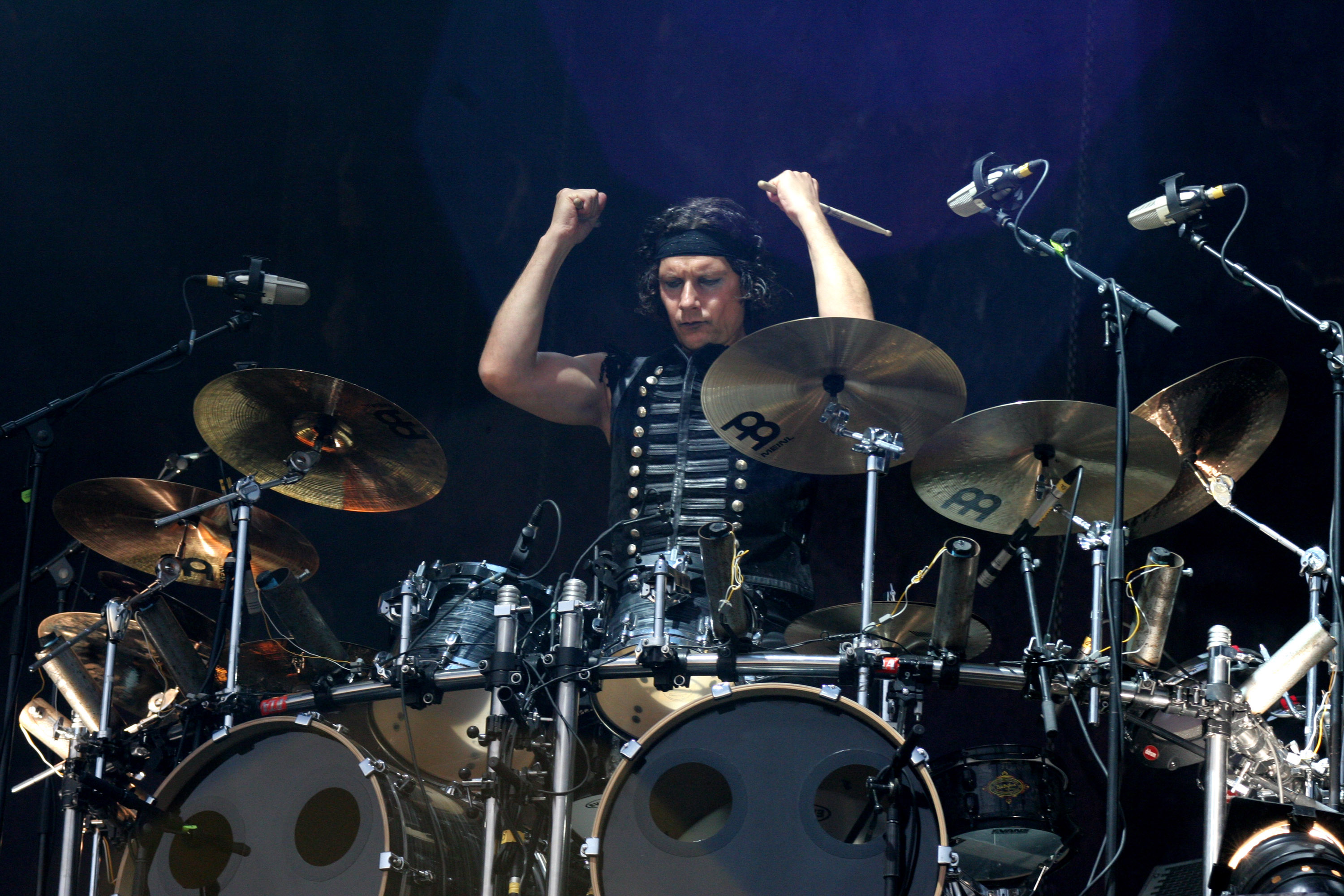

“We were looking for new inspirations and most of them came from the metal world. We listen to a lot of heavy metal bands, Scandinavian bands like Dimmu Borgir, Meshuggah, and I brought this in, with more double bass drums and stuff. I’m the heavy guy in the band, and I can imagine Rammstein to be harder than it is now, but I’m just one guy in the band.” He pauses thoughtfully. “Sometimes I envy artists who work alone, who have freedom to do what they want. In a band like Rammstein you can have an idea but then it has to go through all the other members and in the end maybe only a little bit is left.”

So what does the future have in store for a band whose members all appear to feel that they have to compromise in order to create art? Well, 200 shows in three years if everything goes according to their ambitious plans. Beyond that things seem less certain. Speaking to both Richard and Christoph it’s apparent that the band is an increasingly emotionally draining process, and whilst Paul and Oliver are certainly less candid about matters – perhaps due to the formality of working through translators – they certainly don’t paint an easy picture either.

“I’m thinking sometimes…” ponders Christoph, echoing his bandmate’s sentiments. “Many people would say that I have a great job. I’m in a successful band, I can play drums, which I always wanted to do, so what am I complaining about? But what counts is when you finish the day, can you say it was a good day? Did you do something good or do you feel like you have no energy and feel angry about the other band members? This troubled feeling… If this is taking over too much you can say I don’t have a good life, it doesn’t matter if you play big venues or have lots of success if you don’t feel good.” He sighs deeply. “Sometimes it’s just like that.”

For all their differences Christoph and Richard appear to both be re-examining their reasons for continuing with the band. As the founding member, Richard speaks in almost black-and-white terms, explaining that one has to choose between a ‘meaningful life’ and a ‘happy life’, explaining that one naturally precludes the other. As someone who went to the trouble of fleeing East Berlin during the communist era and pursuing music as career, it’s pretty easy to guess which camp he has chosen. Nonetheless, it doesn’t take much reading between the lines to see that a time may be approaching when the band will take a backseat to the man’s personal life. Thankfully for now the rewards seem to justify the sacrifices.

“At the end of the day it comes back to why you are doing this,” he concludes. “Mostly if you go back, most musicians are looking for the attention they didn’t have as a child – in my case I was second born, my mother favoured my brother and the only way I got attention was to get into trouble. The way I’m seeing it right now is that I had to create something bigger than me to survive, and at one point Rammstein became so big, I felt like I did it for the sake of Rammstein, almost like a religion, you do certain things to serve the religion. Now I do certain things ’cos I know what the outcome will be. If the outcome wasn’t as good or satisfying then I would say it doesn’t justify the pain or frustration I’ve gone through being with the band. And there may come a time when I say I don’t need that anymore – when I say, ‘That was a part of my life and now I want something else.’”