Dave Edmunds: my stories of Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, Keith Moon and more

Dave Edmunds travelled on Led Zeppelin's private jet and spent an afternoon with George Harrison playing Beatles dress-up. These are his stories

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

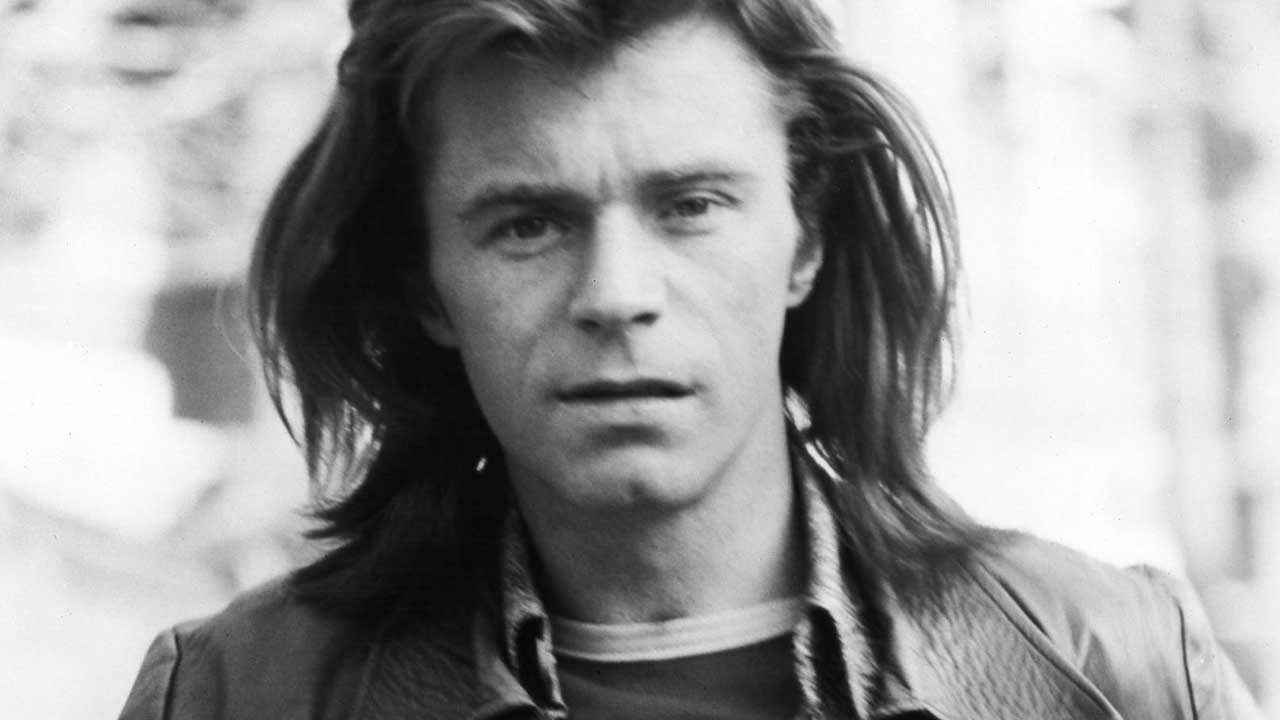

From his humble beginnings as a mechanic in a Cardiff garage, Dave Edmunds has ploughed a diverse and successful musical furrow.

From his lightening guitar work on a novel interpretation of Khachaturian’s Sabre Dance (with his trio Love Sculpture back in 1968) to the pure and simple down-home rock’n’roll of I Hear You Knocking or radio-friendly late70s hits like I Knew The Bride, Girls Talk and Crawling From The Wreckage, Edmunds is a musical journeyman who has performed with and is respected by most of the world’s greatest musicians.

A soft-spoken and humble fellow, here he relates some of his past experiences from his long and eventful musical journey, including having a pint with Jimi Hendrix, knocking back several more with Keith Moon, dressing up with a Beatle, being hailed by the next Messiah by a Beach Boy, and doing a bit of demolition work with John Bonham.

Jimi Hendrix

In about 1968 I had been doing pretty well with a band in Cardiff, and I was a motor mechanic. I decided to hand in my notice and to seek my fame and fortune in London. So I moved up and got a little poky flat somewhere. The places to go then were Giovanni’s in Denmark Street, where all the musos would hang out, and The Ship, a pub in Wardour Street.

I went to The Ship one night, and it just so happened that Jimi Hendrix was playing at the Marquee down the road. All I knew about him was that I’d heard the record Hey Joe and that there was a buzz going round. So I was in The Ship with a friend from Cardiff, and Jimi walked in with a couple of guys and stood next to me at the bar, and we got talking.

He asked me if I liked Eric Clapton and I said: “Oh yeah. But I’m into Steve Cropper and the MGs.” Which he seemed quite impressed with because that Stax thing was still a bit underground. We had a pint, and what struck me was that I’d never met anyone so opposite to their image; he was charming, polite and quite a gentleman. And that impression stuck with me.

When I finally walked out into Wardour Street it was absolutely jam packed, everybody was trying to get into the gig. I heard a rumour that he earned £400 for that show, an outrageous sum of money at the time [laughs].

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Keith Moon

I got call from the head of RCA records, which I was signed with at the time, who told me about this guy called David Putnam who was making [the movie] Stardust, a sequel to That’ll Be The Day, and they wanted someone to do the music for it. I sent them a version of an Everly Brothers song and they said: “Right, you’ve got the job.”

So I went down to Rockfield studios [in Wales] and I was left all on my own to do what I wanted. Then they asked me if I knew any musicians with acting skills, because they didn’t want the band in the film to just be actors. I piped up and offered my services, and I got a job in the film as one of the band members who doesn’t say much.

Keith Moon was in the band, and that was a riot. I didn’t even drink until I met Keith [laughs], I was just a pot-smoking hippie. So there was me, Karl Howman [actor] and Keith; we became the terrible trio of the film set. I remember one time we were on our way to Manchester to film at the Belvue. We were in Keith’s limo, with me and Karl in the back, and we stopped at a service station somewhere on the M1.

When we arrived there was a bus full of schoolgirls who were getting out and assembling ready to go in and eat. Keith had his driver Eddie stop the car, then he took all his clothes off, stripped absolutely naked, and ran in among the schoolgirls, around the petrol pumps, back into the car and off we went. Of course, the schoolgirls scattered like pigeons. Keith used to get away with murder, and if you hung out with him long enough you got the impression that you could too. He got a lot of people into trouble because of that.

George Harrison

I used to hang out with George in the mid-80s and I was often up at his place, to keep him company, because he didn’t get out that much. I went up there one time and there was just me and him in the house. He picked up a guitar and started playing some Beatles songs. He sort of looked at me with a sly grin, as if to say: “You know what you’re getting here.” Normally we just talked about anything other than music. Then he said: “Follow me.”

We got up, went through a corridor, upstairs and got to a huge wardrobe, which he opened and there were a lot of Beatles suits in there: the Shea Stadiums outfits, the silver suits with the black collars; there were also three Sgt Peppers jackets, which we took off and tried on. He laughed and said: “I think I’ve got Paul’s here, but don’t tell him.”

We spent the afternoon trying on Beatles clothes. I was amazed how small they were, these suits were absolutely tiny. I would say that George Harrison was one of the most interesting people I’ve met, and as a musician he knew what he needed to know about music. Like a lot of us, if you were born between 1939 and 1945 you were privy to things that a lot of people might have missed.

Brian Wilson

I’d produced a band called The Flamin Groovies, and they popped over to see me when I was in LA. I was with the band’s frontman Chris Wilson and guitarist Cyril Jordan one night and they said: “Let’s go to Brian’s house.” I said: “What are you talking about?” And they said: “We know where he lives, and we met him once and he said come over.” And I said: “Oh yeah, sure.”

So we hopped into a car and drove up to these gates, Cyril jumped out of the car and said: “It’s Dave Edmunds with The Flamin Groovies” [laughs]. And, sure enough, the gates opened and in we went. We were welcomed into the house by Marilyn Wilson and Stan Love – Mike’s brother – who was doing security. Stan came up to us and said: “Look, I don’t know if you’ll get to see Brian, he’s upstairs in his room. But if you do, don’t give him any drugs.” So I said: “Wouldn’t dream of it. Haven’t got any, and wouldn’t anyway. We understand.”

So we went in. Cyril had a copy of [the soundtrack album] Stardust with him. On it I’d done a real Phil Spector version of Da Doo Ron Ron, the multi-tracking and all that. Cyril put it on the record player. It got to that track, Brian turned up! He came downstairs in his dressing gown, walked into the room; he was huge, about 350 pounds. He said hi and then ignored us. He just walked over to the record player, picked up the needle and put it back on Da Doo Ron Ron.

As it was playing, he walked in a very characteristic way from one end of the room to the other. He’d walk right up close to the wall until his nose was touching it, turn around, and in military fashion he would walk right across the room to the other wall and then turn round again. He did this pacing backwards and forwards until the record ended, then he would put the track back on and do the same again. He did this about three or four times. Then he came over and said: “That’s God on drums,” and then turned round and walked out of the room. We never saw him again. And by the way, I have to tell that it was me on drums [laughs].

The Band

When I was doing the Ringo Starr tour we had a press conference in New York. I had nothing to do that evening. Ringo’s press secretary called me and invited me to see The Band at the Lone Star café in Manhattan, so I went. When we got there she disappeared into the group’s tour bus, which they were using as a dressing room because there was no room in the club.

When she came out she said: “The boys want to meet you.” And I said: “Oh I don’t want to do that,” because I don’t like people doing that to me. And she said: “No, they insist you go in and say hello.” So I went into the tour bus and talked to Levon [Helm] for a bit, because he’d played with Ringo, and Rick Danko. Rick then disappeared into the back of the bus and came back with two guitars, a Gibson and a Fender, and said: “Which one do you like?” I said: “Personally I use both of them, depending on circumstances.”

And he put the Gibson around my neck! I said: “What are you doing?” He said: “We’re on now” [laughs].The next thing I know is that we all walked on stage, someone plugged me in and I ended up playing the whole set with them. We did every song, all the ones you know and love. We did them all! I remember walking back to my hotel that night and I couldn’t believe what had just happened. It was The Band; they were as cool as you could get, and they were the royalty of the music business.

Led Zeppelin

Being on Swan Song was great. How it happened was that I had a few hit records with RCA, we had our own Rockfield label, and the deal ran out and I was free. So I was sitting around at the studio recording, and Robert Plant came down to check out the studios. He had a listen to some of my stuff and offered me a deal right there and then. Within a week I was signed to them [Swan Song] and they gave me a cheque for a load of money. And I had the album ready, with no more studio costs, nothing. That’s the way to do deals.

I went to [Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant and he said: “Alright, Dave, we’ll sign you to the label, but I don’t want to do it with any lawyers. You can trust us. I’ll give you the same deal as Zeppelin’s done with Atlantic.” And that’s what he did! And I recouped on every album. And recoup is good. It was the perfect record deal: I was allowed to do what I wanted.

I would say that the two best people I’ve worked with in the business are David Putnam and Peter Grant. Two more opposite characters you couldn’t meet, but they were the most honourable people that I’ve ever dealt with in this business. I must admit that I felt like their mascot. They were chuffed to have me and I was chuffed to be with them. They took me on tour with them. They had a jet, and we’d take off standing up with a drink, without wearing seat-belts and all that.

Robert was my contact, I didn’t really socialise much with the rest of them. Having said that, I was in a limo in New York with Robert and Bonzo once, and Bonzo tore the inside of the limo to pieces for reasons I never understood. It was an interesting experience travelling with them to see what life could be like with the big boys.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 115, in February 2008.

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.