Breaking down The Beatles: Giles Martin and the miracle of the Revolver de-mix

Giles Martin explains what he learned about The Beatles’ Revolver while remixing (and de-mixing) the 1966 milestone album

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

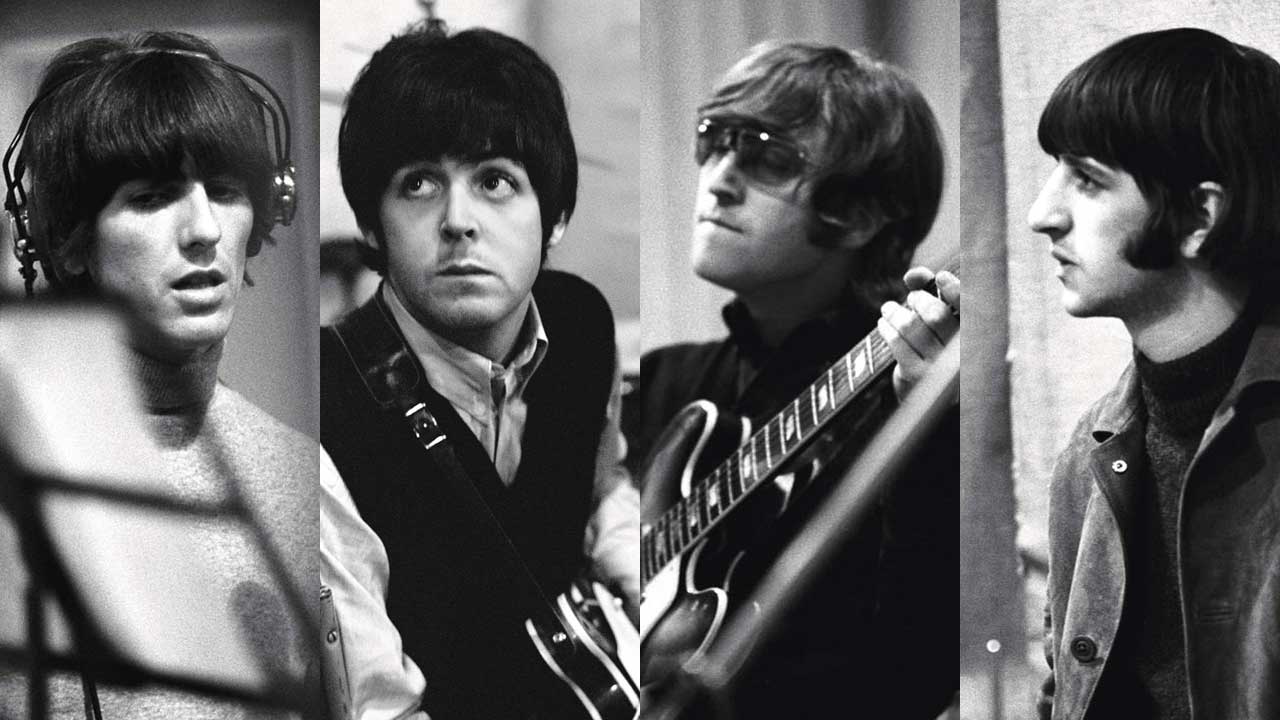

It’s undeniable that the Beatles’ Revolver is a psychedelic rock landmark, a sonic marvel that marked a sea change in music production and culture. And in 2022 it was revisited for the full deluxe reissue treatment.

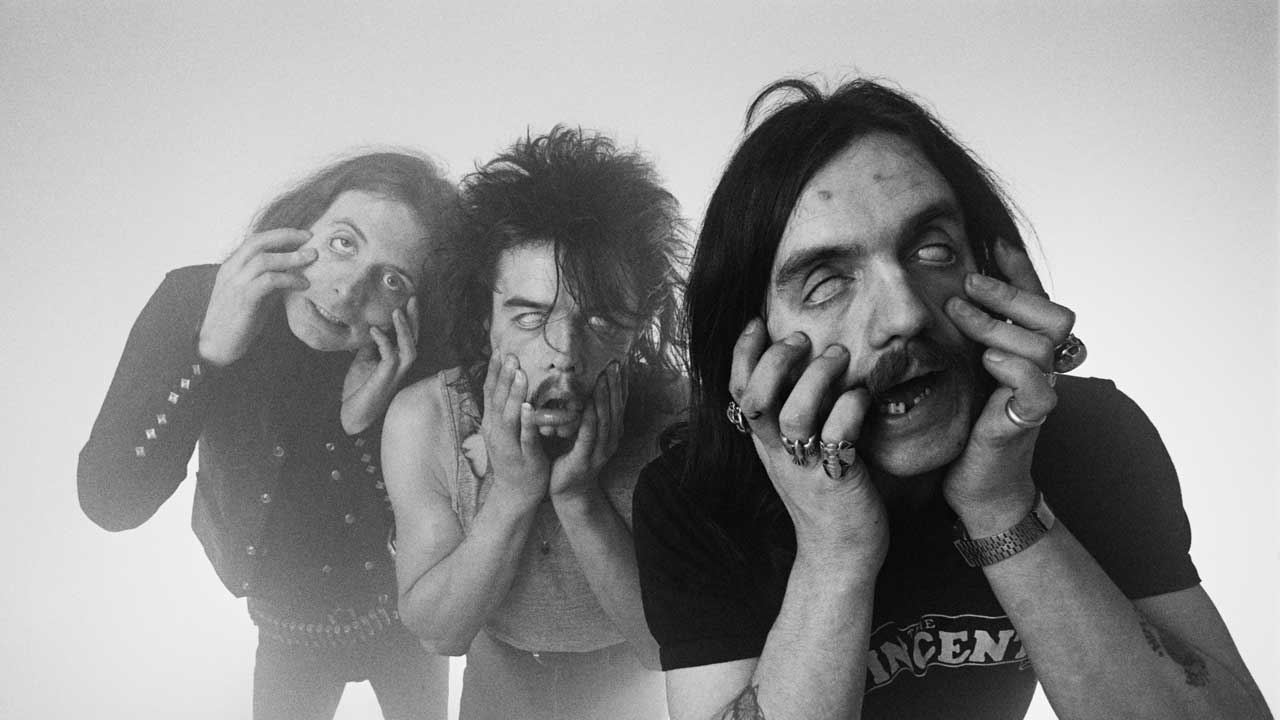

In 1966, joined by their new recording engineer Geoff Emerick, The Beatles and producer George Martin set about using the recording studio as their sonic workshop, creating sounds never heard before and introducing classical Indian music into Western pop rock.

But, like most pre-1968 Beatles albums, Revolver was recorded to four-track tape, with the result that the main rhythm instruments – usually guitar, bass and drums – were placed together on one track, making it impossible to separate them for stereo mixes.

Using ground-breaking de-mixing technology, Giles Martin – George Martin’s son, and the producer behind much of the group’s reissues in recent years – was able to separate the instruments, and even the individual pieces of the drum kit, without losing the room ambience or creating ugly artefacts. Here he explains more.

What were the challenges of de-mixing and re-mixing Revolver?

Well, it’s funny. Geoff Emerick, The Beatles and my dad were pretty good to begin with, and the album sounds pretty good. And, you know, it is very compressed, and I’ve still respected that. But in order to have the band sound like they’re in a room, you kind of have to pull them apart to a certain extent and put some air between them. And on Revolver John Lennon never sings in the same voice. It’s different on every song. Same thing with the guitars and drums. Remixing it was like mixing eight different bands.

It’s come down through history that Geoff Emerick was critical to helping your father and The Beatles create these new sounds. Do you think that assessment accurate?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Listen, Geoff was a genius, yes. But I think it comes from their fingers and the guitars. My dad would say this, and Geoff would have said this as well, I think – before he became too bitter. The sounds came from themselves and their willingness to innovate, especially with guitars. So the disappointing answer for everyone is: it’s the band. And the reason why it’s disappointing is because you’re looking for which knob you can turn [laughs]. And which box you can plug in to. Absolutely – to get that sound. And that’s the tricky thing

There’s a video of you, your father and George Harrison’s son Dhani listening to a ‘lost’ George solo recorded for the Abbey Road track Here Comes the Sun that you discovered. Were there any surprises like that with Revolver?

No. But there was a thing with fuzz guitars. They were originally going to play [on guitars] the horn lines on Got to Get You Into My Life, but they decided to go with brass instead.

Just the opposite of what happened on the Rolling Stones’ Satisfaction.

Yeah! So that exists in a previous version of the song. But because the recordings were four-track, if they didn’t get something right they’d just record over it. So there are no hidden gems. But you really get a sense of their efficiency.

For example Paperback Writer, there’s just one and a half takes of the basic track, which is guitars and drums. So I’ve just left the tape running for this box set. They play, it breaks down, they immediately play it again, and that’s it! It’s all done but the bass and vocals. It’s very efficient.

As well as being a classic album, Revolver is also a psychedelic rock landmark. De-mixing it probably presents you with an opportunity to make it more vivid – more what they might have done at the time had multitrack technology existed.

The tricky thing is, the claustrophobia you get from mono can make things sound more psychedelic, and when you open things up it can sound less so. And the challenge is with something like Tomorrow Never Knows: the expectation is it’s this crazy song. And it is – but it isn’t.

There’s bass and drums, there’s a bit of tamboura, there’s an organ, tape loops… And that’s it. There’s not much going on. So you really have to work at it to create something that satisfies the expectation.

When I was working with [Martin] Scorsese on the George Harrison film [the 2011 documentary Living In The Material World], he questioned my revisionist approach to mixing. Then I played him some stuff I’d done, and he liked it. I said: “I just try to make songs sound how we remember them, not how they are.”

Having literally dissected the Revolver album, what’s your takeaway about The Beatles at that point in their musical evolution?

You can hear them like kids in the back of a car saying: “We’re bored! We want to do something different.” That’s what’s going on with Revolver. It’s like a prog record – kind of like: “Look how many ideas we have!” And what I find fascinating is that they went from being this four-headed monster with Beatles suits on to being these four individuals going in different directions – but helping each other.

Like, no one’s saying: “Come on, John, change chords on Tomorrow Never Knows.” Or, you know: “Why are we doing Indian songs? We’re from Liverpool!” It’s like that pure confidence of jumping out of the plane without a parachute and knowing you’re going to land safely. Revolver is kind of a fearless record.

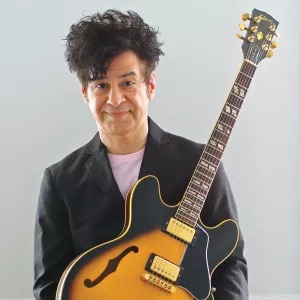

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analogue synthesisers.