The tantalising story of Baby Face, the supergroup that almost was

"Phil’s voice was staggering, wonderful. But he couldn’t play" - the story of the Thin Lizzy-Deep Purple supergroup that could have been

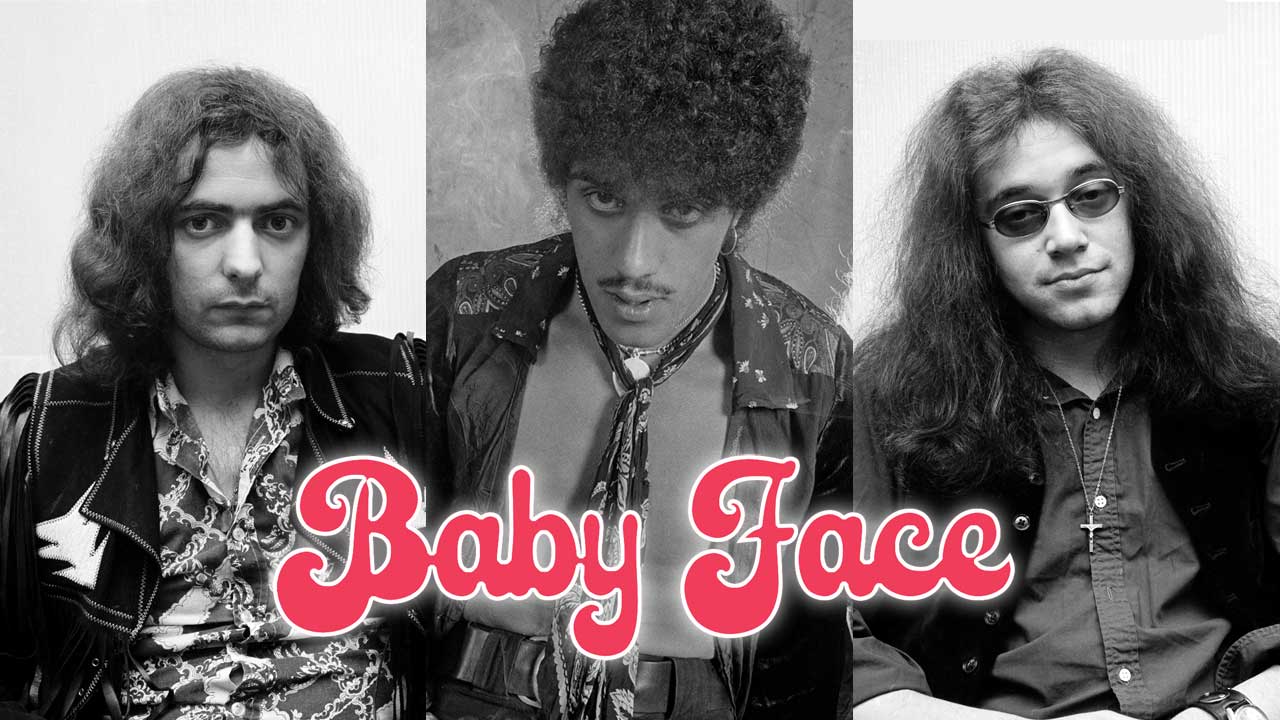

It's one of the great ‘what if’s of the Deep Purple story: the union between Ritchie Blackmore, Ian Paice and Thin Lizzy frontman Phil lynott under the name Baby Face.

In late 1972, Blackmore and Paice approached Lynott with the idea of forming a band that would let them flex their muscles outside their increasingly strained confines of deep Purple. Lynott had come to the guitarist‘s attention after he heard Lizzy’s self-titled 1971 debut album.

“Ritchie used to love his singing,” says Purple tour manager Colin Hart. “Kind of like a young Rod Stewart or Paul Rodgers.”

“We’d see Phil Lynott with Thin Lizzy at the Speakeasy club in London really early on in their career, and we thought: ‘Wow, what a fantastic voice'," says Ian Paice. "But we didn’t actually pay a lot of attention to his bass playing, because he was such a great vocalist. So we thought we’d try something out – me, Ritchie and him."

With Thin Lizzy yet to make a big breakthrough, Lynott took Blackmore and Paice up on their offer. Settling on the name Baby Face, the guitarist instructed Hart to arrange an impromptu session at De Lane Lea studios in London, where Made In Japan would be mixed less than a year later.

“They did a couple of covers,” says Hart, who was in the studio with them. “It was only a short session, two or three songs, then it was out with the equipment and off home. I don’t think they did anything original. It did sound great together, the three of them.”

“It was meant to be a free-flowing kind of thing,” recalls Paice, who says the reason nothing came of Baby Face was purely musical. “It never got off the ground mainly because Phil wasn’t really a good enough bassist yet.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Phil’s voice was staggering, wonderful. But he couldn’t play, at least not to the standard that we needed if it was just Ritchie, myself and a bass. When there’s only three of you, everybody’s got to be really good on everything they do.

"Really, the bass playing had to be on a par with someone like Jack Bruce. And, God bless him, Phil wasn’t there yet. He was pretty simple, and quite often out of tune and out of time. And although he became really, really good at everything he did, at that point he wasn’t.

“Ritchie and I looked at each other and went: ‘It’s not working. It’s a nice attempt to try and do this three-piece thing, but let’s go and rethink it.’ But we never did rethink it. We got back on the road with Purple and it just sort of disappeared into the mist.

The connection between the two bands didn’t end with the aborted collaboration. The name Baby Face would end up being used as a title on Lizzy’s next album, and the Irish band would record a Deep Purple tribute album in 1972 under the name Funky Junction (though vocals would be provided by Benny White of Irish group Elmer Fudd)

But, for a brief moment, the prospect of an early-70s supergroup was tantalisingly close. “Phil was bowled over by Blackmore,” Lizzy drummer Brian downey later said. “That was the first time I’d ever seen him hesitate about anything.”

“I saw Phil a couple of times after that," says Paice, "but it was always really in passing: ‘Hey, how you doing? Gotta go. Bye bye.’ But the ship had sailed by that time.

“We actually recorded the session. The tapes got lost somewhere along the line, but really there was nothing to it. We didn’t even bother mixing it. It just wasn’t happening.”

The story didn't quite end there. With Ian Gillan on his way out (his final Deep Purple Mark II show was in Japan on June 29, 1973), Blackmore and Paice were still apparently making noises about wanting to develop the Baby Face project with Lynott – and maybe even bringing Paul Rodgers on board as well.

Such was the grind of the rumour mill that Thin Lizzy’s management were forced to issue a denial to the press, saying that Lynott had absolutely no plans to record with Blackmore and Paice again. And he never did.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.