Lars Ulrich: Why Vinyl Matters

Why Vinyl Matters is a book that gathers together testimonials from across the music world to explain the joy of vinyl records. Here's Lars Ulrich's contribution

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

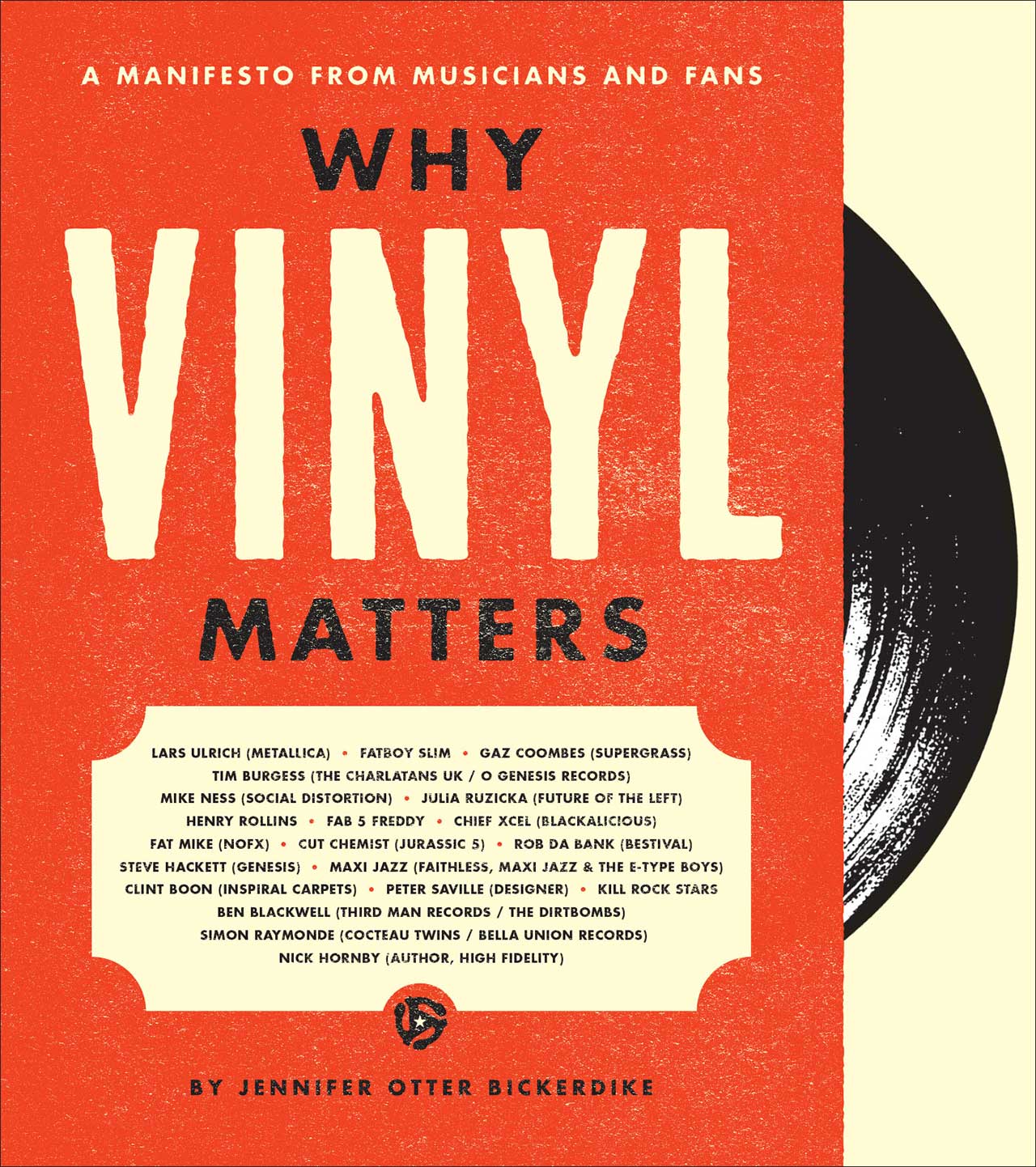

“It took a journey to the brink of extinction for us to realise how important the physical record is in defining self, community and culture,” says Jennifer Otter Bickerdike, author of Why Vinyl Matters: A Manifesto from Musicians and Fans. “The story of the album’s inception, burst in popularity, decline and rebirth reads like a fantastical version of David and Goliath.”

Why Vinyl Matters collects a series of testimonials together, with contributions from musicians, industry figures and fans. Amongst rock’s great and good offering their thoughts are Henry Rollins, NOFX’s Fat Mike, Steve Hackett, Social Distortion mainman Mike Ness, sleeve designer Peter Saville, author Nick Hornby and Record Store Day founder Michael Kurtz.

Below, Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich relates his own vinyl history, going back to the time when the nine-year-old Lars picked up a copy of Deep Purple’s Fireball, kicking off a love affair that’s lasted to this day…

What was the very first record you bought, and what did it mean to you?

When I was 9 years old, in 1973, my dad took me to see Deep Purple in Copenhagen. The next day after school, as I was biking home, I stopped off at the record store. It was out in the suburbs where I lived, a run-of-the-mill local chain. I asked what Deep Purple records they had. They had Fireball – so I bought Fireball. And that was the beginning of it. Over the next couple years, as I was growing up in Copenhagen, I bought a lot of Sweet, Slade, Status Quo, Deep Purple… A lot of singles, a lot of 45s… This was 1974-1977. A few years later, I started migrating more towards hard rock: Thin Lizzy, Rainbow, Judas Priest – that kind of stuff.

What place does the brick-and-mortar record store have in today’s culture?

Probably a significantly different one than when I was running to record stores on a daily basis. The record store at that time, for me, was not just a place where you bought records. It was the place where you browsed through records; it was the place where you first encountered records; it was a place of social significance. It was a place where you heard from the knowledgeable store clerks what was coming out, what was going on. That was in the pre-internet days. Living in a place like Copenhagen, Denmark, we didn’t get a lot of English or American periodicals, so the record store clerks were a key source of information. It was a place of great importance for a 12, 13, 14, 15-year-old snot-nosed kid like myself at the time.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It was the centre of my music universe. My store was a three-level place called Bristol Music Centre. Of course, the hard rock department was down in the basement – duh! There were two or three fellows running it. One was a guy named Ken Anthony. A highlight of my teenager years was when Ken invited me back to his apartment in the southern outskirts of Copenhagen to look through his private record collection. I thought I had died and gone to music heaven.

When I moved to America in 1980, it was right at the height of the new wave of British heavy metal.It was hard rock’s answer to the Do-It-Yourself punk attitude a few years earlier: independent records, people releasing 7-inches out of their basements. At the height of this – which was sort of 1979-81 – I used to get all of these 7-inches and 12-inches sent to me. There was a mail-order company in England called Bullet Records. They specialised in hard rock. The bands would press up to 500 copies of some 7-inches and 450 of them would go to Bullet Records because that was the place where the hard rock mail-order community lived.

I would get all these records sent to Newport Beach, which is where I moved to in America. Also, my guy Ken Anthony, he would send me records of stuff he was getting his hands on. There were very few records stores in Southern California that stocked hard rock. I would drive up to Hollywood; there was one place in Long Beach, there was a place in Costa Mesa called the Music Market. They were very, very few and far between. If they ever got anything in, they would only get one copy. So I had a lot of it sent to me.

Do you still talk to Ken Anthony?

Ken Anthony has played a role in Metallica’s career! When we came to Copenhagen in 1984 to record our second album, Ride the Lightning, penniless and starving – the usual sob story – we ended up staying in Ken Anthony’s apartment, the very same apartment I visited three or four years earlier as a snot-nosed 14-year-old. We came – the whole band, all four members of Metallica – and stayed in his apartment for two months in the spring of 1984 when we were recording. There you go: full circle.

What is the joy of the album release for you?

It’s the ritual element of it. It’s running your finger down the side to try to open the plastic wrap, and usually cutting that part under your nail. Then pulling it out, and seeing if there’s an inner sleeve, and hoping for a gatefold. Nowadays, you just walk over to your computer, you click three times, and you have 140,000 songs at your fingertips. It was just a different kind of thing – and it still is.

I still have all of my old records. I still occasionally take them out. I would be lying to you if I said there was no nostalgic undertone to the whole thing. It’s just nice to be able to sit down and listen to music for no other reason than to sit down and listen to music. When you’re in your car, music is an afterthought. You put some music on when you’re cooking in the kitchen, or when you’re sitting on an airplane and staring out the window, bored. It’s a background function to some other activity. You used to put a record on for no other reason than to sit down and completely immerse yourself in the music, the lyric sheet and the pictures; sit there and dream your life away. It was pretty cool.

For every fad, there are a significant number of people who run in the opposite direction. So, for everything that is popular, there are people who seek out alternative ways to the mainstream. That’s the nature of pop culture, that is the nature of human beings and humanity in general. Now that most people experience music through compressed MP3s – in subways, in airplanes – I think there are a lot of people who seek out alternative ways just because.

So vinyl’s resurgence is, in part, the anti- MP3. I think people are looking for better sound quality, looking for a more physical relationship to music, and probably a more one-on-one relationship with music rather than it being just a background element. I am not knocking it; I am just saying an increasing amount of people seem to want to experience music in a way that has a different depth.

I have three boys. The oldest one enjoys walking to Amoeba Music up here in San Francisco on the Haight and looking at records; but also looking at books, looking at DVDs, looking at paraphernalia, looking at posters. Maybe it’s a broader experience than it was for me, when it was purely records. Most music that comes out now, especially by popular artists, enjoys a limited edition run of vinyl which is a huge collector’s item. It feels like it’s not only back again, but it’s probably not going to go away.

I don’t think it’s going to come and go and come and go. Whether it’s going to keep increasing its presence or just level off at some point in the next few years, I don’t think it’s going to dip much. I do think there are a fair few people who enjoy the contrary elements of going to the store, buying the physical record, and dealing with the sleeves. Listening to vinyl is an experience that often has a social interaction attached to it. But more so than anything else, it involves a non-mobile, stationary requirement in the fact that you are not in a motor vehicle, you are not in an airplane, you are not in a subway. It’s an experience that requires more effort from you. It demands more attention.

Obviously, there are an increased number of people who are falling back in love with this and embracing it once again. I can certainly see this in my 17-year-old. The last two Christmases and birthdays, he has asked for particular favourite records of his on vinyl. He has a little shitty $50 record player in his room. Occasionally, when I walk in there, I would say one out of 15, 20 visits, it’s actually a Radiohead or Arctic Monkeys or a Miles Davis on vinyl that’s playing, which certainly warms his dad’s nostalgic heart. So there is hope!

Why Vinyl Matters is on sale now.

- The best classic rock vinyl you need to own

Online Editor at Louder/Classic Rock magazine since 2014. 40 years in music industry, online for 27. Also bylines for: Metal Hammer, Prog Magazine, The Word Magazine, The Guardian, The New Statesman, Saga, Music365. Former Head of Music at Xfm Radio, A&R at Fiction Records, early blogger, ex-roadie, published author. Once appeared in a Cure video dressed as a cowboy, and thinks any situation can be improved by the introduction of cats. Favourite Serbian trumpeter: Dejan Petrović.