What the Unstoppable Rise of Guns N' Roses Looked Like From The Inside…

Paul Elliott – the only UK journalist at the LA launch party for Appetite For Destruction – remembers the drugs, women and chaos surrounding GN'R.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

March 17, 1987. It was just another beautiful day in LA. The sun was shining, the Hollywood Hills a blur of green through the smog, Sunset Boulevard thrumming with late afternoon traffic.

In a small hotel room just off Sunset, I sat facing the five members of Guns N’ Roses, the hottest new band in LA. On the floor, cross-legged, was singer, Axl Rose, shirtless under a fake-fur coat. Beside him, rhythm guitarist Izzy Stradlin pulled another cigarette from his pack of Marlboro Lights. On the bed were drummer Steven Adler, lead guitarist Slash and bassist Duff McKagan, the latter having only just woken up after I’d been interviewing the band for an hour. The room was filled with cigarette smoke, the floor littered with empty beer bottles. In the far corner, the band’s manager Alan Niven was keeping a watchful eye on his charges.

Guns N’ Roses’ debut album Appetite For Destruction was to be released in the summer on the heavyweight Geffen label, and I was in LA to interview the band for UK rock magazine Sounds. The previous night I’d seen them play live at legendary Whiskey A Go Go club, just a half a mile away up Sunset. They sounded good, and they looked great. Axl, certainly, had the aura of a star in the making. But still, I wasn’t sure about Guns N’ Roses.

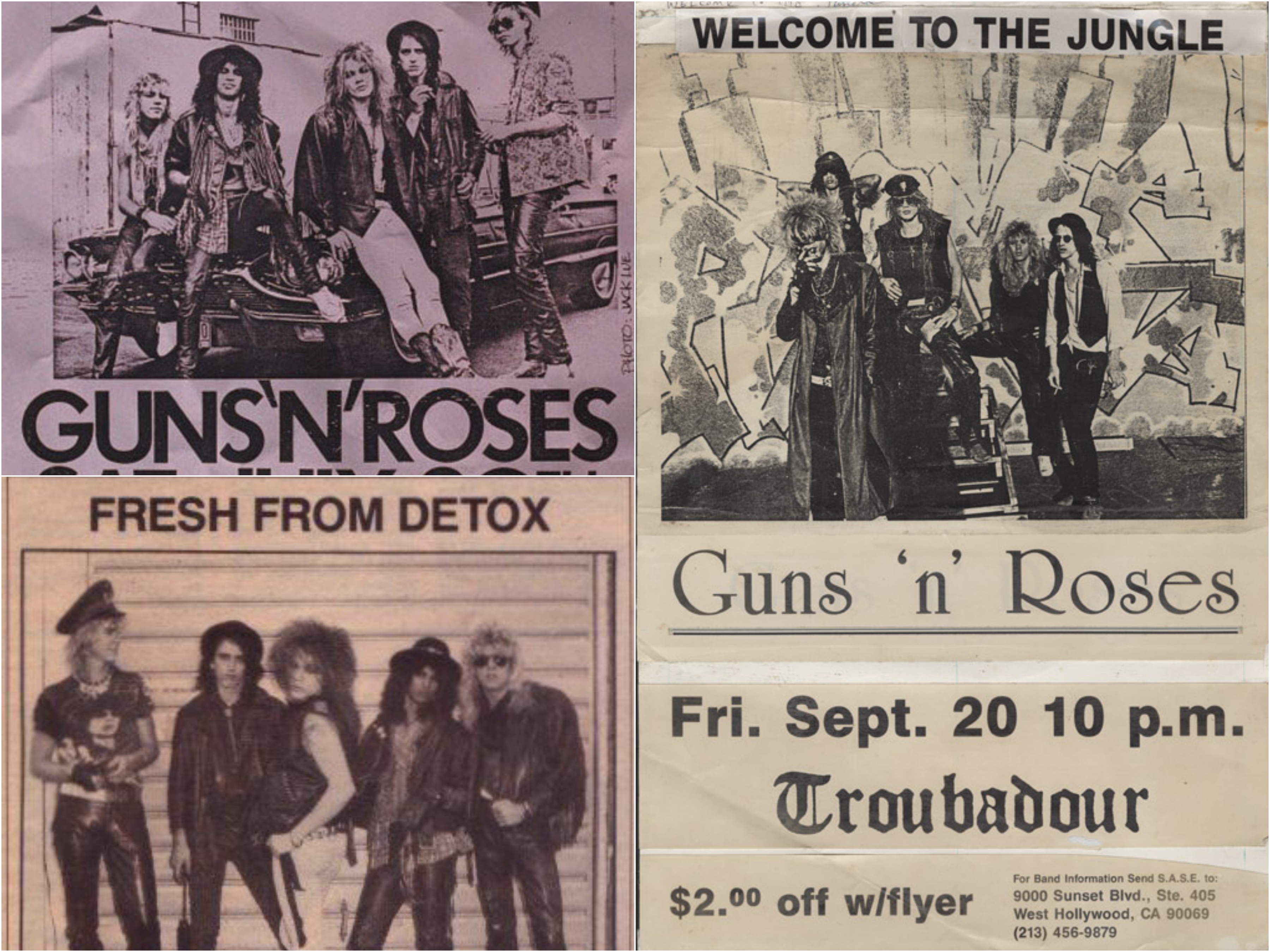

I’d heard their EP Live Like A Suicide, and it was pretty good, but in the photo on the EP’s sleeve Guns N’ Roses looked like any one of a thousand LA hair metal bands. Tougher than Poison, maybe, but that wasn’t saying much. During the interview they’d talked a good fight. They trashed other LA bands and said they were different, better. But every rock band said that. Until I heard the album, the jury was out.

Slash produced a Walkman from inside his black leather jacket and walked over to me. “Listen to this…” he said. As the rest of the band watched, he placed the headphones over my ears, dialled the volume up to very loud and pushed ‘play’. What I heard was a rough mix of a song from the album: a song called It’s So Easy. And it was electrifying. The riff just slammed into me. It had the punk rock fury of the Sex Pistols mixed with the swagger of Rocks-era Aerosmith. It was mean and dirty, really nasty stuff. Axl sang the verses in a low sneer, full of venom. And just when it seemed like this song couldn’t get any better, Axl snarled, “Why don’t you just… FUCK OFF!”

Slash was grinning as he clicked off the tape and took the Walkman from me. I just smiled back at him, speechless. I simply couldn’t believe what I’d just heard. This one song was a hundred times better than anything on the EP. And if the rest of the album was as good as this, Guns N’ Roses weren’t just the best band in LA – they were the best band in the world.

“This is the only real rock ‘n’ roll band to come out of LA in ten years,” Axl had told me that day. “Van Halen was the last.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

I had to agree with him. In 1987 hair metal was still at its peak and LA was its spiritual home. Kings of the Sunset Strip scene were Motley Crue, the self-proclaimed Bad Boys Of Hollywood, whose hedonistic excesses had assumed mythic proportions. The Crue had sold millions of records, but Izzy Stradlin got it right when he dismissed them as “teen metal” – in essence, kids’ stuff. And the same could be said of Poison, the prettiest of LA’s pretty boys. “Poison fucked it up for all of us!” Axl stated bitterly. “They said everybody was following their trend.”

From the outset, Guns N’ Roses were keen to distance themselves from the hair metal scene. They felt an affinity with Metallica, who had relocated from LA to San Francisco five years earlier because LA was full of bands that looked – and played – like girls. As Metallica fan Slash put it, “LA is considered a pretty gay place, and we get a lotta flak from people thinking we’re posers.”

I knew Slash was right, because I’d been one of those people. When I walked into the Whiskey the previous night, I saw cliché upon cliché. Girls in micro-skirts, spike heels and skimpy tops, some wearing little more than lingerie, had their hair fluffed up like extras from Dynasty. The guys’ coiffures were just as big, and some of these dudes – ‘chicks with dicks’, as they were called – were wearing more make-up than the girls. This was LA’s in-crowd, posers all, and Guns N’ Roses were their new darlings.

The Whiskey had a glorious history. It had staged so many legendary gigs, from The Doors and Led Zeppelin to Van Halen and the Ramones. But I didn’t go into that place thinking I was about to see the future of rock ‘n’ roll. In truth, I was more interested in the other band I would be interviewing a few days later during that trip: Slayer, who had just released the awesome Reign In Blood. Now there was an LA band with a difference. Surely Guns N’ Roses couldn’t compete with that?

Jet Boy were the support act that night. They had a charismatic singer in Mickey Finn, who sported an outrageous electric-blue Mohican. Plus, they had Sam Yaffa, ex-Hanoi Rocks, on bass. But Yaffa looked lost up on that stage, almost dazed, as if the demise of Hanoi, prompted by the death of their drummer Razzle, had sucked all the life out of him.

Guns N’ Roses had idolized Hanoi – and this much was immediately apparent when they kicked into their first song, Reckless Life, a blast of fast and loose rock ‘n’ roll with a punk/glam edge that was pure Hanoi… except for one crucial difference. Where Hanoi’s Michael Monroe sang with a sardonic punk sneer, Axl Rose was a full-on screamer, more heavy metal. And there was something about Axl, an intensity, that Monroe never had. Both had a certain girlish prettiness, but Axl had a menacing aura: the kind of guy who’d punch your lights out as soon as look at you. Stripped to the waist, his slender arms covered in tattoos, his skin almost translucent under the stage lights, hair whipped into an artful mess, Axl was magnetic, drawing all eyes to him.

Slash was the perfect foil for Axl. His face was hidden under a mop of dark curls, cigarette screwed into his mouth, effortlessly cool, swaying backwards as he fired off solos. Izzy was GN’R’s Keith Richards, sullen and nonchalant. Duff McKagan had the air of a displaced punk rocker, tall and thin, the way bass players should be. Steven Adler looked the archetypal Californian beach bum: big blond hair, fuzzy chest. He could have passed for David Lee Roth’s kid brother. And he was the only one who smiled.

Guns N’ Roses meant business. That much was evident on the night. They rocked hard, they looked cool, and the songs they played from the new album – Welcome To The Jungle, It’s So Easy, Nightrain – pissed all over anything that Motley Crue or Poison had ever come up with.

After the show, a Geffen executive told me he reckoned Guns N’ Roses had the potential to be the biggest band in the world. I was reminded of something the band’s UK press officer had said to me before I flew out to LA. “They’ll make it,” she said, “if they live.” Certainly, GN’R had a heavy reputation. British writer Xavier Russell had nicknamed them Lines N’ Noses, and it was widely rumoured that at least three of the five band members were heroin addicts. Maybe it wasn’t just a question of whether Guns N’ Roses could live up to the hype. Rather, could they live long enough to live up to the hype?

“The only reason we get that ‘bad boy’ shit is because the other bands in LA are such wimps,” said Slash when I suggested to him that GN’R were simply the latest in a long line of fucked-up California rock bands. Slash was drunk and in belligerent mood. But then, he’d been drinking all day. Getting drunk, he said, was the only sure way to beat a hangover. And he’d been celebrating into the small hours after the Whiskey gig.

I’d met the band around noon at the Hyatt House hotel on Sunset. It was another of LA’s famed rock ‘n’ roll haunts, where Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham had ridden motorcycles along the hotel’s corridors, thus earning the hotel its nom de rock, The Riot House. Even its rooftop pool area was famous as the venue for the end-of-tour party in This Is Spinal Tap.

I found the band in the Hyatt’s ground floor open-air restaurant. It wasn’t hard locating their table: it was the one full of hairy men swigging bottled beer, chain-smoking cigarettes and irritating the other diners with their loud banter. All of the band members were wearing shades to shield their bleary eyes from the midday sun.

Izzy Stradlin was the most talkative of the five. He was keen to know what was happening on the British music scene, what new bands were breaking through. Alan Niven revealed his plan to bring the band over to the UK in June for three shows at London’s Marquee club. Niven was certain that GN’R could make an immediate impact in the fast-reacting British music scene: a hunch that would prove a tactical masterstroke.

All the while, Axl Rose listened intently but spoke little, impassive behind mirrored aviator shades. When he did speak, his voice was surprisingly low, quite unlike his onstage screech. He chose his words carefully, and was noticeably more sober than the others. Axl, it seemed, wasn’t one for small talk.

After an hour, it was decided that I would interview the band in my hotel room at the Park Sunset, right across the street from the Hyatt. It was certainly intimate, with the five band members, plus Niven and myself, squeezed into one budget-priced room.

As the interview progressed, it soon became apparent who was running this show. Axl was the band’s chief spokesman. Slash and Izzy said their piece. Steven, like most drummers, had less to say. And Duff, like the alcoholic he was, fell asleep.

Axl began by revealing how he and childhood friend Izzy had come to LA from Indiana to form a band. “People used to say to us, ‘You guys should go to California’. And when we got here, we found we were five years behind the times. You show up and think you’re gonna fit in, and they say, ‘So what boat did you get off?’”

I asked if LA was any better than Indiana. “Must be,” Izzy said. “I’m still here!”

“Growing up in Indiana, we got a lotta shit,” Axl recalled. “I got thrown in jail over twenty times, and five of those times I was guilty. Of what? Public consumption – I was drinking at a party, underage. The other times I got busted cos the cops hated me. So I don’t have much love for that fucking place!”

Nor did he have much love for his adopted hometown, claiming at one point that he would leave LA as soon as the band had completed its first world tour. “The LA scene has died,” he said, “and the reason is us. As soon as we began headlining we brought in different opening bands like LA Guns and Faster Pussycat, and it kinda created this scene. Eventually we quit playing for a while to work on the record, and the others started headlining, but I’ve noticed that some of them haven’t been as cool about helping other bands out. We always tried to help others, because I wanna see a really cool rock scene. I wanna be able to turn on my radio and not be sick about the shit I’m gonna hear.”

Slash had no time for other LA bands. “The thought of the LA scene just makes me sick,” he sneered. Steven, the band’s only native Californian, was well qualified to comment, “In LA there’s a million people who think they’re musicians and only a few who are.” Axl added with a laugh, ‘We know one guy who’s been going to the Rainbow for about four years, telling girls he’s in such and such a band, and he couldn’t play his way out of a wet paper bag!”

I asked how the band survived before they signed the deal with Geffen. “Sold drugs, sold girls,” Izzy said matter-of-factly. “We’d throw parties and ransack the girl’s purse while one of the guys was with her.” To which Slash added, mischievously, “Not being sexist or anything, but it’s fucking amazing how much abuse girls will take!”

Slash was smiling when he said that, but Izzy wasn’t when he made his casual reference to selling drugs. Clearly, Guns N’ Roses exulted in their bad reputation. I put it to them that another source at Geffen had told me Guns N’ Roses “take everything”. First there was laughter. “We were just gonna ask you about this bed here…” Steven joked. Then silence… and then, a rustling noise from the corner of the room, where Alan Niven was holding a copy of the LA Times. He shook the paper again and Axl swiftly brought the subject of drugs to a conclusion. “Yeah, we take everything – and that goes in every single way. We take everything from what we hear, from what we see and do…”

Was Niven really sending him coded messages? He never admitted it. But Axl was certainly a shrewd operator, and in that interview he proved much smarter than the average rock singer. What surprised me was his open-minded attitude to music. He cited Aerosmith as GN’R’s key influence: “In my mind, the hardest, ballsiest rock band that ever came out of America was Aerosmith. What I always liked about them was that they weren’t the guys you’d want to meet at the end of an alley if you’d had a disagreement. I always wanted to come out of America with that same attitude. Fuck, they were the only goddamn role model to come out of here!”

Yet he also stated, “In the last year I’ve spent over $1300 on cassettes, everything from Slayer to Wham!, to listen to vocals, production, melodies, this and that.” Few rockers would ever have admitted to buying a Wham! album. Similarly, few people in the late 80s thought Lynyrd Skynyrd were cool, but Axl did. He praised them as the inspiration for a song he referred to as simply Sweet Child (later given its full title Sweet Child O’ Mine). “In Indiana,” he said, “Lynyrd Skynyrd were considered God – to the point that you ended up saying, ‘I hate this fucking band!’ And yet for Sweet Child I went out and got some old Skynyrd tapes to make sure we’d got that downhome, heartfelt feeling.”

Most surprising of all was Axl’s grand mission statement. “We’ve got our progressions already planned out,” he declared. “You know, how we’re gonna grow. This record’s gonna sound like a showcase.”

It sounded like a plan for world domination. And when Slash played me It’s So Easy, I started to believe it.

It was around 3pm the following day that Sounds photographer Greg Freeman and I arrived at the band’s communal home, affectionately known as ‘The Hellhouse’. A smallish, detached two-storey home on a quiet street just off the busy Santa Monica Boulevard, it had seen better days. The white paint on its wood-panelled walls was flaking. The lawn was dead, and no wonder: several cars were parked on it.

Duff and Slash were sitting on the front porch, beers in hand. They’d had another heavy night. So heavy, in fact, that they ended up being thrown out of the Cathouse, Hollywood’s leading rock club, after trashing the pool room. Blame it on the Jim Beam, Slash said.

A few minutes later, the rest of the band emerged from the house. Axl sported a black leather ensemble – jacket, pants and peaked cap – plus the obligatory snakeskin boots. He posed for photos on roadie Todd Crew’s custom-painted Harley Davidson before gathering the rest of the band around him for group shots (one of which would eventually be reproduced on the inside cover of Appetite For Destruction). And as the camera clicked away, a tape of the whole album boomed out at deafening volume from an enormous ghetto blaster. Every track was a killer. Clearly, It’s So Easy was no fluke.

It was around 30 minutes into the photo session that the cops showed up. Three LAPD black-and-whites pulled up on the opposite side of the road. Only one officer emerged, walking slowly over to the house and enquiring with a wry smile, “Where’s the party?” Duff replied wearily, “We ran outta beer.” The cop said he’d received a complaint from a nearby resident about the noise, and warned us that he’d be back in 20 minutes. But as he headed back across the road, Axl called out after him. “Hey, how about we take a couple of pictures on your car?” The cop shrugged and said OK, and the band got their picture, perched on the hood. “That’s the third lot of cool cops in a row,” Axl told me, grinning broadly.

The cops hadn’t returned by the time we left the Hellhouse an hour later. I had a feeling they’d be back again sometime soon. But as it turned out, the local residents didn’t have to suffer much longer. Within a couple of weeks, Guns N’ Roses had moved out. And for the next two years, they’d be constantly on the move, out on the road, wreaking havoc all around the world. First stop: London.

Guns N’ Roses’ reputation preceded them. On June 6, 1987, The Daily Star warned of the imminent arrival of these “booze-crazed rockers” and branded Axl a “dog killer”! “I have a personal disgust for poodles,” Axl had said, tongue-in-cheek. “Everything about them means I must kill them.” But the joke was lost on The Star.

The paper also reported a police raid on the band’s “sleazy hideout” – The Hellhouse – which had resulted in a “vicious battle” that left the singer in intensive care for three days. There was more than a grain of truth in that story, as Axl admitted. “I got hit on the head by a cop and I guess I just blacked out. Two days later I woke up in hospital with electrodes over me.”

Clearly, not all of LA’s finest were “cool” with Axl. He preferred the ‘softly softly’ approach of British bobbies, whom he encountered on June 18, the night before the band’s debut UK performance at the Marquee. Axl had visited Tower Records at London’s Piccadilly Circus with Alan Niven and Geffen’s Tom Zutaut. Having bought an Eagles album, Axl was sitting on a staircase, feeling jet-lagged, when he was pulled up on to his feet by two members of the store’s security staff. The inevitable jostling and shouting match ensued before police were called. To Axl’s surprise, when Niven told one of the policemen, “Take your hands off me”, they did. “Back in LA they won’t take any of that shit,” Axl laughed. “You’d get a gun to your head!”

Guns N’ Roses, and Axl in particular, seemed to attract trouble wherever they went. And it was no different when they played that first Marquee gig. The band were buzzing about playing in Britain, home to so many of their favourite bands: The Rolling Stones, Queen, the Sex Pistols, Led Zeppelin. Niven had told them all about the Marquee, its history every bit as rich as the Whiskey’s. But not everyone in the audience at the Marquee that night was ready to welcome Guns N’ Roses with open arms. For a couple of local rock bands that considered the Marquee their turf, these cocky American wankers needed cutting down to size.

Opening up with Reckless Life and one off the new album, a thumping rocker aptly titled Out Ta Get Me, GN’R were met with a hail of plastic beer glasses and a shower of gob. I remember wincing as a big, sticky lump of phlegm stuck in Izzy’s hair. Axl was having none of it. “Hey, if you’re gonna keep throwing things we’re gonna leave!” Jeers rang out, but by the end of the third song, You’re Crazy, the barrage was over. Guns N’ Roses had passed the test.

The Cult’s singer Ian Astbury was so impressed that he went backstage after the show to invite GN’R to tour with his band in America. But Astbury’s enthusiasm wasn’t shared by Sounds writer Andy Hurt. When Axl saw Hurt’s review of the gig, in which his singing was likened to the squealing of a hamster with its balls trapped in a door, he was livid and led the whole band to the Sounds office in Mornington Crescent, north London. “Andy Hurt?” he raged. “He fucking will be if I find him!” But the reviewer was absent, so Axl contended himself with a warning note left with another member of staff, and the band retired to a nearby pub, where they noted an item on the food menu that left them scratching their heads. Axl asked me about it when I visited the band’s rented apartment in Kensington a few days later. “What the fuck is Spotted Dick?” he frowned. His confusion was understandable. I decided not to mention faggots: Axl would get around to that subject later, in the controversial song One In A Million.

I had an advance tape of the album by then, but at that apartment in Kensington I heard a demo recording of a song that hadn’t made the cut. Just the instrumental track: Izzy and Steven sang the vocal parts as they played it to me. One of the lines would appear at the end of the album credits: “With your bitch slap rappin’ and your cocaine tongue you get nothin’ done.” That song, You Could Be Mine, would eventually appear in 1991 on Use Your Illusion II.

Guns N’ Roses left London for LA at the end of June following the third and final Marquee show on the 28th. Alan Niven’s strategy had paid off: Guns N’ Roses were the talk of rock fans and critics all over the UK. And when Appetite For Destruction was at last released, on July 21, it was immediately hailed as a classic.

Memorably described by one reviewer as “rawer than a whore’s thighs”, Appetite was the best hard rock record since AC/DC’s Back In Black. It was also precisely the kind of record that ‘parental advisory’ stickers were made for. Nine out of 12 songs made explicit reference to sex; four to drugs; four to drinking; three to fighting.

Appetite was loud, rude, obnoxious – gloriously and unapologetically so. But, crucially, it wasn’t one-dimensional. Back in LA, Axl had told me, “I sing in five or six different voices, so no one song is quite like another.” And what a range he had: wailing like a police siren in the intro to Welcome To The Jungle, jive talking on Mr. Brownstone, blowing a fuse on You’re Crazy, and revealing a sweet vulnerability on Sweet Child O’ Mine. Axl got everything right on that record, every last ad-lib. “Axl knew what he wanted,” said the album’s producer Mike Clink. “It was an instinctive thing.”

Clink himself was in a sense the unsung hero of Appetite For Destruction. As Alan Niven stated years later, “I cannot imagine another human being having the patience to get that record made. This band was so fucked up, they made the New York Dolls look as ambitious as Bon Jovi!” Clink, whose previous credits included Survivor’s Eye Of The Tiger, said simply: “I pushed them to work really hard. I had one rule: no drink and drugs in the studio. And if they ever did drugs there, I never saw it.”

Alan Niven had modest expectations for the album. “I believed that if we could keep a degree of discipline in place, we could get that record to gold.” In America, that meant half a million sales. Mike Clink was a little more confident. He recognised Sweet Child O’ Mine as Guns N’ Roses’ secret weapon: a potential hit single. “It was magical – it made the hairs on my arms stand up.” He told Tom Zutaut that Appetite would sell two million. Zutaut disagreed: he predicted five million.

But initial sales were slow. Only 10,000 copies of the album had been sold in the UK when Guns N’ Roses returned in October 1987 for five dates in 2-3000-seat theatres. It was a bold move, but their hand had been forced. Originally they’d been booked to support Aerosmith in the UK: thousands of tickets had been sold. But Aerosmith cancelled when their Permanent Vacation album took off in the US.

Guns arrived in the UK with fellow LA sleaze rockers Faster Pussycat as support act. I travelled up to cold and rainy Manchester for the opening night at the Apollo. Only a thousand people showed up. The balcony was completely empty. But it didn’t matter. Kicking off with It’s So Easy, GN’R played a brilliant set, and afterwards they were in buoyant mood backstage. Axl showed me a souvenir given to him by a fan who’d made the long journey down from Scotland for the gig. It was a ticket for a show that never was: Aerosmith plus Guns N’ Roses at the Edinburgh Playhouse.

The tour concluded with a near-sell out date at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, during which Axl spoke at length about a friend of the band’s who had recently died in New York – their roadie Todd Crew. Todd had been with them on their first trip to the UK but had passed out drunk for the whole of that first Marquee gig. Now he had died of a heroin overdose. The band played Bob Dylan’s Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door in his memory.

Heroin cast a long shadow over Appetite For Destruction. It was there in My Michelle, the story of Axl’s friend Michelle Young, whose mother had died a junkie. It was in Mr. Brownstone, a song named after a notorious LA drug dealer. And it was in Paradise City, which Duff McKagan had written aged 19 while living in Seattle with a junkie girlfriend and dreaming of escaping to LA. “Of course, when I got there,” he noted, wryly, “the band I joined ended up with three heroin addicts in it!” But not even the death of a close friend such as Todd Crew was enough to shock them into cleaning up. As Duff would later reveal, “Slash and Izzy and Steven were out of their fucking minds.”

And their condition was unlikely to improve given the band’s next public engagement: a US tour in November supporting Motley Crue, whose leader Nikki Sixx was himself a fully-functioning junkie. Putting the Crue and GN’R together seemed like a recipe for disaster, yet, miraculously, they all survived – only for Sixx to OD and almost die at a party in LA mere days after the tour had ended. Slash had been with Sixx at that party, but claimed, “I didn’t know Nikki had OD’d – I was passed out drunk in the bathtub.”

Soon after, Slash was sent to a rehab facility in Hawaii. He told me later, “It hurt me – I spent eight days in fucking hell!” But it would take another two years before Slash faced up to the truth about heroin: when Steven Adler, his friend since childhood, paid the price for his addiction by losing his job and all the dreams that went with it.

- Why I Love Appetite For Destruction, by Myles Kennedy

- Guns N' Roses: The Wild Ones

- Guns N' Roses: Review Of Their First Ever UK Show

- Guns N’ Roses: Appetite For Destruction

In February 1988 Guns N’ Roses were back out on the road, headlining in US theatres. But when a gig in Phoenix, Arizona was cancelled, rumours quickly spread of a split in the band. It was alleged that Axl had failed to show for the gig, and that when he reappeared 24 hours later, the rest of the band told him he was fired. Only after three days of mediation, instigated by Slash and Izzy, was Axl reinstated.

If the rumours were true, Guns N’ Roses had almost imploded just as they were on the brink of a major breakthrough. The combination of heavy touring and strong support from MTV had seen Appetite pick up momentum on the US Billboard chart. By May 1988, when the band supported Iron Maiden in North America, the album had already gone gold, surpassing Alan Niven’s prediction. By June it was in the top ten. And in July – exactly one year after its release – Appetite For Destruction was the number one record in America. The fact that it knocked politically correct singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman off the top spot made it all the sweeter.

On July 23, nine months on from our last meeting, I joined the band on tour in Dallas, Texas, where they were supporting Aerosmith. At last, that dream double-bill was a reality, albeit in America and not poor old Britain. I was writing a cover story for Sounds to coincide with GN’R’s forthcoming appearance at the Monsters Of Rock festival at Donington Park on August 30.

The band was staying at the Four Seasons hotel, a luxurious, five-star palace with its own private golf course. I found Izzy and tour manager Doug Goldstein in the bar, taking refuge from the 100-degree late-afternoon heat. Goldstein was grumbling about having his early morning round of golf disrupted by Steven and Duff, who had commandeered two golf buggies for a race across the course. “They looked like the fucking Banana Splits!” Goldstein hissed.

Izzy asked me for my room number so that we could arrange a time for an interview, and was shocked when I told him I was booked into a different hotel, a cheap one, a few miles away. He cursed the record company and said he’d pay for me to have a room at the Four Seasons. I said not to worry, but it was a nice gesture. Izzy was often portrayed as a surly character, when in reality he was simply more introverted than the others.

I asked Goldstein when I could speak with Axl. Goldstein wasn’t sure. He told me Axl was “resting”.

That night, Izzy took his English girlfriend Emma to see a Rod Stewart show at the venue where Guns and Aerosmith would play the following night: the Starplex, a 20,000-capacity outdoor amphitheatre. “It was very relaxing,” he told me the next day, “like a Quaalude.” Everybody else went to a rock club to celebrate Slash’s 23rd birthday: everyone, that is, apart from Axl, who hadn’t been seen by any of his bandmates since they arrived in Dallas. Was he sick? Goldstein said no. Would he do an interview with me? “Tomorrow,” Goldstein said.

Inside the club a roped-off VIP area had been set aside for the band and its entourage, 20 or 30 people, including various groupies and hangers-on. I had a long, drunken conversation with Steven Adler and Megadeth bassist Dave ‘Jr.’ Ellefson that ended when Adler dragged a girl off to the men’s room. He and many others were in and out of there all night.

In the early hours we returned to the Four Seasons, where Duff invited photographer Ian Tilton and I to his room. Duff had recently married an aspiring musician named Mandy Brix, and was feeling a little lonely. He poured out three tumblers of vodka and added in just enough orange juice to turn the mixture slightly cloudy. Then the phone rang. It was Slash, telling us to come to his room. We took our drinks with us. Moments later Slash opened his door, shit-faced drunk and naked save for a towel wrapped around his waist. He waved us inside, where a girl lay in his bed, completely starkers. “Thanks for coming, guys!” she sneered. Even Duff didn’t know where to look. We got out of there as fast as we could… after Ian had taken some pictures of the happy couple.

We were back at the Four Seasons the following afternoon to ride out to the venue with the band. We sat on the tourbus for a few minutes – I asked if we were waiting for Axl. Izzy shook his head. Axl, he said, would be along later. The atmosphere on the bus was subdued; everyone was pretty hungover. But the mood lifted at sound-check. They played around with a couple of old Stones songs, and Duff – wearing shorts and cowboy boots – tried on Ian’s newly purchased Stetson. He liked it so much he asked if he could wear it for the gig.

After sound-check there was still no sign of Axl. Nobody – not Goldstein, nor the band – seemed concerned about it. But to me it felt weird. Ever since that first time I’d met them, Guns N’ Roses looked an acted like a gang. They had that ‘us against the world’ mentality. But now Axl was on a different schedule to the others. Maybe he was just resting, as Goldstein had said. But after those rumours about Axl being kicked out of the band in Phoenix, it didn’t look good.

Just 90 minutes before GN’R were due onstage, I interviewed Izzy and Slash in a large backstage toilet-cum-shower room. Slash was revelling in the band’s phenomenal success. “It’s completely against the industry,” he said, proudly. “What this industry’s about in the ‘80s is pretty obvious – trying to polish everything up. Everything’s like techno-pop, even heavy metal stuff. We go against every standard of this industry. Even when we play live to 20,000 people, we’re like a club band. We do whatever we feel like doing. That’s just the way it is. And if people come expecting us to play hit after hit, it just ain’t gonna happen.”

On this tour, however, there were some rules that GN’R had to abide by. Aerosmith, formerly the most fucked-up band in America, were now teetotal and drug-free, and in an effort to keep them sober, their manager Tim Collins had drawn up a contract forbidding Guns N’ Roses to drink alcohol outside of their own dressing room. GN’R honoured that contract out of respect for their heroes. “The vibe between the two bands is great,” Slash smiled. “These guys have been through a lotta shit and we have a lot of respect for them. We grew up listening to their music, this and the Stones and AC/DC, that’s what sorta formed what we are. And it’s funny – they don’t do drugs, they just like to talk about them. They love to ask you about what you did last night and how fucked up you got.”

Izzy added, laughing, “You drag your ass into the gig sometimes and you see these guys and you think, Awwww, fuck! They’re eating watermelon and drinking tea and they go, ‘Man, I’ve been up since nine o’clock this morning’, and you say, ‘What drugs are you doing?’, and they say, ‘No, I just been up since nine!”

I suggested to them that few people would have believed that Guns N’ Roses would have survived 14 months of touring like they had. Izzy snorted, “They didn’t expect us to last a week! But touring really doesn’t faze you. if you get twisted backstage, the walk to the bus is only a few yards, y’know? But yeah, if you get twisted every night, you start draggin’…”

Of course, I had to ask them about Axl. I’d been around the band for 24 hours and I still hadn’t seen him. Slash was quickly on the defensive. “You gotta understand that with this bunch, excess is best and all that shit. Axl knows he has to keep from smoking or drinking or doing drugs to maintain his voice. He doesn’t hang out that much because the atmosphere that’s created by the other four members of this band is pretty, uh…”

Izzy cut in: “…Conducive to deterioration.”

“Axl just hangs out by himself,” Slash continued. “He takes it all pretty seriously. He’s doing well to maintain a certain sanity level, seeing as he can’t go out cos of his position in the band. If he was doing what we were doing, he wouldn’t be able to sing at all!”

When I mentioned the rumours about the band firing Axl in Phoenix, Slash responded like a seasoned politician. “That’s been one of the stories that’s gotten bigger than all of us,” he sighed. “And, as little as it was, it’s past tense and it’s not worth talking about cos it doesn’t relate to what’s going on now.”

We returned to the dressing room, where Steven was drinking vials of royal jelly. “Builds up cum in your balls!” he explained. Somewhat belatedly, Doug Goldstein presented a birthday cake to Slash with a message in pink icing: ‘HAPPY FUCKIN’ BIRTHDAY, YOU FUCKER’. A pack of Marlboro Reds, his preferred smoke, had been squished into the cake.

20 minutes before show time, Slash and Izzy were jamming on acoustic guitars, Steven rattling his drumsticks on the back of a chair, when, at last, Axl arrived. He barely acknowledged the other members of the band before disappearing behind a ring of flight cases arranged in corner of the room. Hidden from view, Axl went through his pre-gig warm-up ritual, singing to a loud playback of The Needle Lies, a track from Queensryche’s concept album Operation: Mindcrime. The meaning in the song’s title wasn’t lost on anyone.

Axl emerged from his den just as Aerosmith singer Steven Tyler entered the room, causing general panic as everyone with a beer in their hand tried to hide it. Tyler seemed oblivious: he just wanted to congratulate GN’R on their number one album. He hugged them all and quickly left. Axl disappeared again to change from jeans and t-shirt into his stage gear: leather chaps and codpiece, snakeskin jacket and wide-brimmed leather hat.

He looked surprised when he saw me. He walked over, his bangles and spurs jingling, and we talked for a few minutes. There was no time for a formal interview. I told him what Slash and Izzy had said about him earlier, and he seemed happy enough with that. He appeared distracted, which I attributed to him being psyched up about going on stage. But even when he broke away for Ian Tilton to take a band shot, he seemed apart from the rest of the group. The dynamic between them had changed. The isolation of Axl Rose had begun.

Guns N’ Roses were brilliant that night: the best show I ever saw them play. At times, Axl was in playful mood, swapping cowboy hats with Duff. But his focus was absolute. Aerosmith might have been the headliners on that tour, but Guns N’ Roses were the main attraction, and Axl owned that stage. Just before they’d gone on, Ian Tilton had asked Doug Goldstein if he could shoot from the side of the stage. “Not unless you want to eat a mike-stand…” Ian asked me if that was a joke. I assured him it wasn’t.

Guns N’ Roses whipped the Texan crowd into a frenzy. Standing beside me at the mixing desk in the centre of the arena was Slayer’s Tom Araya, a broken arm in a sling and a beer in his good hand. Even between songs he had to shout right in my ear, such was the noise from the crowd. It seemed ironic that Araya was there. Just 18 months earlier, I’d travelled to LA thinking Guns N’ Roses were nothing compared to Slayer. And now GN’R were on a different level altogether.

Guns N’ Roses were a phenomenon. They had the world at their feet. But their enigmatic singer was already withdrawing into a world all his own.

But then fame can mess with your head. Earlier that day at the hotel, Izzy, Slash, Duff and Steven had appeared in the lobby and were immediately mobbed by a group of pre-teen kids. Izzy smirked as he signed autographs. “Maybe they think we’re Bon Jovi,” he whispered in my ear. Seconds later, the kids all ran off. Izzy looked bemused until we realised where they’d gone – to the other side of the lobby, where they were crowded around another celebrity who had just arrived: A-Team superhero Mr. T.

If ever Guns N’ Roses required a lesson in the fickle nature of showbiz, they got it right there.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”