“We came up very fast and we went down fast. We were carried away on that wave of euphoria”: how Motörhead made their two most controversial early 80s albums

The story of Motorhead’s divisive Iron Fist and Another Perfect Day albums and the chaos that surrounded them

By the autumn of 1981, everyone knew Motörhead. Whether revered as the kings of greasy biker grebo, fast’n’loose dirty rock’n’roll, or reviled as the sort of dirty ruffians who turned everything up to 11, drank too much and flipped dirt-encrusted middle-fingers to the dull and boring British public, Lemmy, Philthy Animal Taylor and Fast Eddie Clarke were news to everyone. Their popularity was at an all-time high: No.1 albums, Top 10 singles and even an appearance on children’s TV show Tiswas had seen them emerge as one of Britain’s top bands. Lemmy even got away to record a single featuring The Young & Moody Band plus The Nolan Sisters, Don’t Do That…

Not that they ever took any time to revel in the fruits of such labour. Indeed, the answer to this almost bizarre level of success was for their management at the time to keep them on the road, to keep them working and speeding along, to keep them on a relentless cycle of touring which saw them never really get any time off. This was soon to prove a major problem, but in August 1981, life was sweet.

The band started their initial recording work for the Iron Fist album with Vic Maile at Jackson’s Studio in Rickmansworth, the partnership having enjoyed outrageous success with the previous two albums and so obviously feeling the good work would continue. It’s tough to know exactly how much pre-production and writing the band could’ve done, but it wouldn’t be a wild guess to say not much, simply because Motörhead never seemed to take the time to write! The lure of the road – sex and drugs and rock’n’roll – was ever-present. And so a ‘studio break’ was called while venues across Europe took another beating from Motörhead and support act Tank, a London-based punk-metal band whose sonic assault was very much in the Motörhead vein.

When the tour ended, Fast Eddie went into Ramport Studios with Tank and produced their debut album Filth Hounds Of Hades, along with Eddie’s old pal, Will Reid-Dick. It was an event that was to have a profound impact on Motörhead.

Clarke didn’t care for Vic Maile’s work with Motörhead, and promptly announced to Lemmy and Philthy that he would handle production duties for Iron Fist, along with Reid-Dick. Lemmy and Philthy reluctantly agreed. So at the end of January 1982, Motörhead strode into first Morgan and then Ramport Studios to continue recording Iron Fist with Clarke and Reid-Dick at the controls.

Reid-Dick came with a high pedigree himself, having been an engineer on significant albums by Thin Lizzy and Saxon, but the problems with Iron Fist lay somewhere between the break-up of a successful partnership with Maile, Clarke’s relative inexperience and Motörhead’s lack of creative preparation. It sounded at the time like an album that needed another level of work, another couple of months of time and a strong hand at the helm to shake the extra dimension from Motörhead that …Spades had.

Clearly, Iron Fist was never going to be a direct sibling, but the dovetail between Mack-truck power and subtle humour which …Spades had was just out of focus on Iron Fist. Tracks like Loser felt distinctly like hastily written filler, and even the nifty riff on Shut It Down sounded bored of itself and in need of some coffee, fresh air and a cigarette.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Perhaps the most frustrating thing about Iron Fist is that the potential for greatness was alive and kicking, if only more time had been spent writing and recording it. Because some of the songs on the album were absolute belters; classics even. The title track was to become a familiar set-opener for many years, and Speedfreak had that deliciously filthy bass tone sitting on the riff.

Then there was the brilliant (Don’t Need) Religion, which saw Lemmy malevolently expound on one of his favourite targets with some of his finer lyrics (‘Don’t save no knee-pads for me up there/If your head’s alright, you don’t need binoculars to see the light’), and which remains one of Motörhead’s darkest and most adventurous songs.

Truth be told, Iron Fist was a classic example of the era. Strike while you’re hot, get it out and don’t stop to smell the flowers. Looking back, it’s hard to figure out exactly where the trio found time to write any songs for …Fist, let alone work with them for longer than an A.D.D. minute. Forensic science dictates it must’ve happened between the hours of 3am and 9am on Friday and Saturday nights around Christmas 1981, but truth be told, nobody has a clue. Somehow it happened.

“I didn’t like Iron Fist,” Lemmy said. “We let Eddie produce it, which was a mistake. It was also following No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith, which didn’t help. The next studio album after a great live album is always going to sound a bit wet.”

It’s hard not to look with a degree of cynicism at their former manager during this era. Doug Smith, Lemmy’s old friend and a man who had doubtless put up some serious cash to help Motörhead get to where they were, was not exactly one to forcibly direct the band to take a breather. And so as the Motörempire grew greater, the workload remained relentless, and the branding of the band became a thing of legend.

The War-Pig had established itself as one of rock’s most popular images, which made Motörhead T-shirts an international best-seller. Not that the band necessarily saw the returns – they were too busy on tour! And as long as their needs were met (fags, booze, drugs, cheese sandwiches and small fluffy partridges flown in specially from Norfolk), they were happy enough to barrel along. With any twinges of business acumen and hindsight stuffed in a closet, three of the hardest, fastest and loosest rock’n’rollers steamrollered forwards with little thought of future consequences.

“See, this is now where I live, on this bus,” stated Lemmy. “I am no good for anything else. My life is over as far as ‘sitting down to dinner with a few friends’ goes. You can forget me, I am a road clone. I love sitting in that front seat and watching the sun come up…”

Iron Fist was released on April 17, 1982, but the Iron Fist tour had already begun. If you’ve ever wondered where Lemmy’s palatial abodes (you know, the ones he earned from …Spades and No Sleep…) went, you’d have seen them in the production values of this absolute barnstormingly mental night out. The set opened with a live band playing very loudly, but not visible. Instead, fans peered into an empty space where the stage should’ve been but wasn’t. That’s because moments later, the stage, the band, their gear and a ton of lights were visible to all who looked up, descending from the sky like that enormous fuck-off spacecraft from Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, support being offered by four enormous metal chains.

Once safely in place on the floor, a huge iron fist could be seen behind Philthy Phil, and at the end of the show, he would fall into the fist, which would then close! If you’re going to spend the vast majority of your hard-earned cash on your own show, it could be argued that this was the way to do it, because Motörheadbangers far and wide still speak of this tour with reverence.

I can personally tell you that I went to all four Hammersmith Odeon shows, and I feel safe in saying that most of the staff working on this magazine who are of a similar age were there for all of them too. Of course, looking back it was classic Motörhead – move fast, do things impetuously and worry about the money, well, never.

“To summarise, we came up very fast and went down just as fast,” said Lemmy. “We spent a lotta money doin’ all these big stage sets and bringing them all over the world. A lot of the time we didn’t look after our money and neither did our management, but we were all being carried away on this wave of euphoria, that indescribable rush.”

In May 1982, a seemingly innocuous side project would result in the implosion of a line-up absolutely no one could’ve imagined apart. Lemmy got together with Wendy O Williams, the irrepressible, fun, sparky and diminutive frontwoman for New York shock rockers the Plasmatics, to record a cover of country singer Tammy Wynette’s classic hit Stand By Your Man. A harmless little bit of fun if taken on face value, but an unknown storm must’ve been brewing, unrecognised and unaddressed, because it became a back-breaker.

Clarke was never enamoured with the idea and did not play guitar, but agreed with some hesitation to produce the session. With Reid-Dick in tow, Clarke was not happy about the difficulties Williams found in getting her performance to a strong place. This led to increasing tension, and further reinforced Clarke’s view that the collaboration was not good for Motörhead. Matters became heated, and a good ol’ fashioned studio barney ensued. There was no thaw post-ruckus. Indeed, word has it that Lemmy had everyone wearing Plasmatics shirts on the bus the next day in a display of visual sarcasm. Lemmy has always possessed a wickedly deft (or in this case, sledgehammer!) sense of humour, but Clarke didn’t see the funny side whatsoever.

The rot was so rapid that within a week of the studio door closing, Fast Eddie Clarke had left Motörhead mid-tour. In typical fashion, Motörhead just kept moving forwards, head down, a steam train not about to be derailed even by this seemingly unnavigable event.

Into the frame came Brian Robertson, the Scottish guitarist who had made his name as a member of Thin Lizzy in the 70s, playing on such classic albums as Jailbreak, Johnny The Fox and Live And Dangerous. Robertson also had a fearsome reputation as a whisky-drinking hardman whose behaviour was so wild that it had led to him being fired by Lizzy, one of the hardest-living bands in all of rock’n’roll.

Philthy Phil loved Thin Lizzy and especially Robertson’s playing. So when he and Lemmy found out Robertson was recording an album in Canada, they made the call. Robertson was happy to come out and help Motörhead complete their North American tour, things going so well that he further agreed to stick around and join the band for what would undeniably become their most controversial career phase.

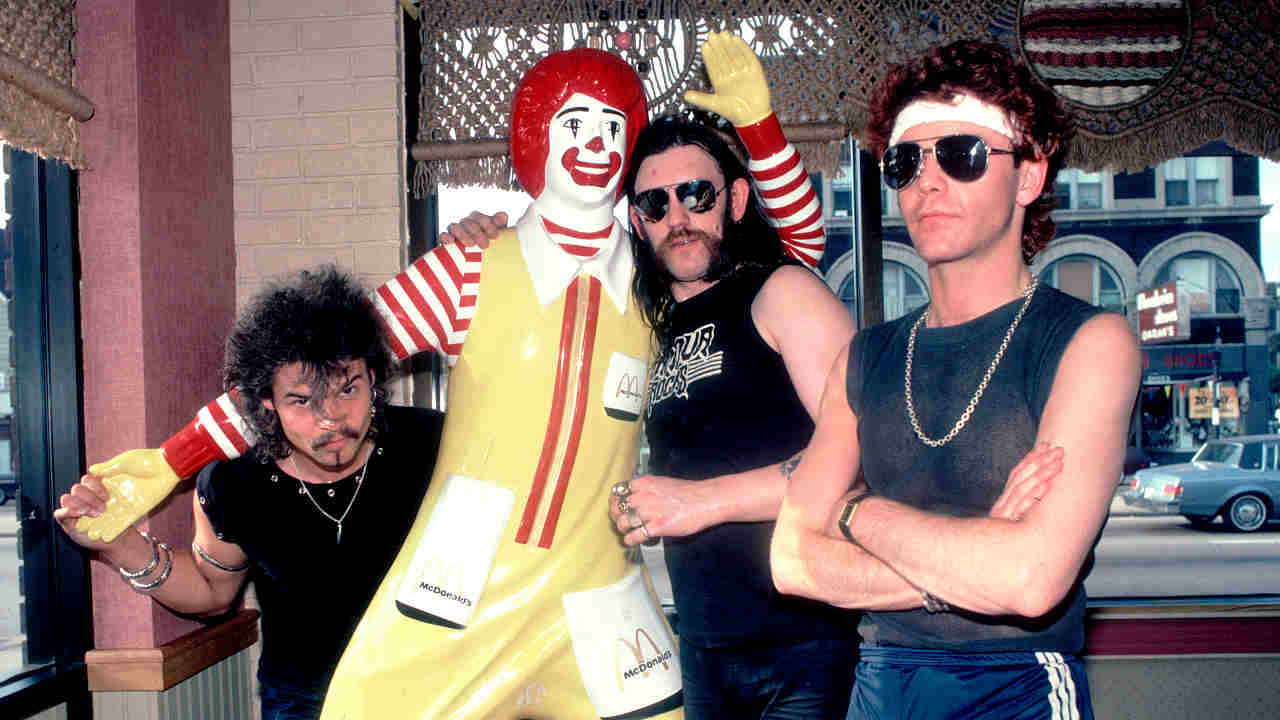

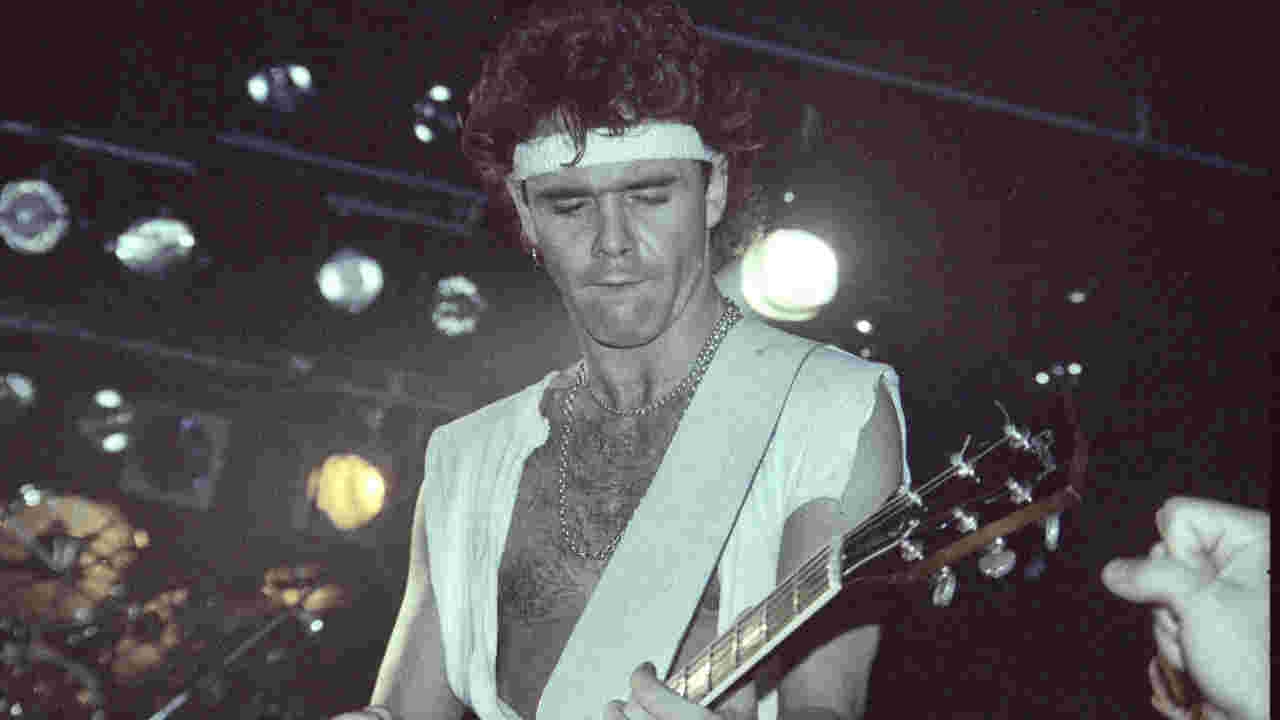

Robertson was not one to offer the slightest of what he viewed as personal concessions. At one of his very first live British appearances, the Hackney Speedway Festival in July 1982, he insisted on wearing tight shorts and a black mesh disco vest with a white headband and tennis shoes. It could only have been more shocking had Lemmy joined him! In the grand scheme of things, it was perhaps not the smartest choice of attire when introducing yourself as the new guitarist for Motörhead, especially not at a Hells Angels-operated festival. So when Robertson compounded this first impression further by firmly refusing to play any of the band’s established classic songs, the die had been cast, the public were furious and Lemmy had to placate more than a few people. It was an inauspicious start, to say the least.

Robertson brought a lyrical edge to both the guitar sound and writing process, which was certainly different from Clarke’s more aggressive, attack-minded performance. Both loved their blues, but while Clarke had a very clear frame of how he felt a Motörhead guitar should sound, Robertson enjoyed experimenting. The result, 1983’s Another Perfect Day, was one of Motörhead’s greatest musical achievements, an album brimming with scope, superb songs and some supreme guitar work.

This writer was invited, as a teenage school magazine scribbler struggling with the weight of ‘O’ levels, to join Lemmy and co at Olympic Studios in London to hear a mix of the album. With a pint of vodka and orange thrust in my hand, my arse shoved firmly into the producer’s chair and Lemmy showing me where the volume fader was on an enormous mixing desk, Back At The Funny Farm blew the few facial hairs I’d tried to grow clean off my 15-year-old baby face and I proceeded to be pinned back by this quite sensational stew.

I remember the beauty and terror of the moment, song after song roaring from studio monitors, Lemmy having given me full licence to turn up the volume. I turned it up as far as the fader would go. I tilted backwards in the studio chair and I didn’t leave until I’d heard Another Perfect Day twice. It was clean, crisp yet still with enough definitive dirt to feel like Motörhead. But it was absolutely not even close to oily-denim grebo fare. This was a stealthy beast stuffed with variety, refusing to sit on old riffs and ideals, reaching out instead for melody and variation but never sacrificing power.

At the time, reaction was frighteningly poor. Fans felt betrayed on several levels, and few could get beyond the idea of Robertson and his disco gear to allow their ears to offer a greater perspective. It was, admittedly, a big ask, one which required enormous willpower, but one which offered great reward to those prepared to seek. Shine signalled something blisteringly new – clear melodies, wrapped neatly in a minor key and augmented by Robertson’s stunning lead work – while Rock It was a snarling jaw-snapper with swagger, sass and a thunderous piano for texture. And Lemmy fucking loved it! Every Chuck Berry-flavoured, hip-swinging goddamn minute of it. Even the lead-fisted hammerhead of Die You Bastard enjoyed Robertson’s flourishes, leaving an album which 30 years later is revered by Motörheadbangers as a belting classic.

The wave of negative press started building. Aside from a hopelessly one-sided defence of both Another Perfect Day and Motörhead in Sounds magazine (written, as an intern, by me), the knives were out. Put simply, this was an aesthete’s revenge, and it’s worth contemplating whether a pair of jeans, some boots, a normal fucking shirt and the odd live classic on Robertson’s part might’ve changed perspectives.

The 1983 tour was, by Motörhead’s standards, just north of a disaster. Towns which only 12 months earlier had hosted multiple nights now struggled to sell out one. Fans were unable to disengage from the mesh vests and white headband, and Robertson steadfastly refused to play Bomber, Overkill and Ace Of Spades. There was no stage on chains from the sky, no Bomber lighting rig and no giant fist. As my spotty memory recalls, there were these purple/blue fluorescent neon tube lights adorning the amps, but the main point is that these shows were not spectacular visual feasts – they were spartan. Add the crushing lack of typical Motörhead production to every other change and it was only the hardest of hard-core fans that took note.

There was word that a love affair with alcohol was not helping matters and quickly, distance between the band members grew. Creatively, the gel was powerful and positive, but as people, walls were being built. Lemmy found himself caught in a crossfire between knowing how strong the material had been, but recognising that the public had no time for Robertson’s belligerent disregard of Motörhead traditions. Besides, he was seemingly always moaning about something or other.

“Brian Robertson was great. I just couldn’t get along with him, but he was a great player,” Lemmy said. “Robbo used to say, ‘There is no bass! How can I do this? Can we set up another bass drum? I need bass.’ I said, ‘What makes you think that I wanted bass?!’”

With attendances down, classics consigned to a lock-box and increasing unhappiness between the band members, it was agreed that Robertson would leave Motörhead, his last appearance being in Berlin during November 1983. The writing, it is fair to say, had been billboard-sized on walls worldwide.

There is little doubt it was a relief for most Motörhead fans at the time, but that fantastic mirror to the past now suggests that even one more album of Robbo-generated material would’ve seen some great songs. Of course, what it also would’ve done is rob us of a soon-to-be classic guitar feast and a man who would rewrite the band’s history and establish himself as Lord Axesmith of the Motörhead guitar legacy…

But we’ve stepped slightly ahead. It’s important to realise just how utterly in the doldrums Motörhead were at that moment. Take a deep breath and consider the three-year span from 1980 to ’83. No.1 metal band, an immortal smash-hit single with Ace Of Spades, No.1 album with No Sleep…, another smash-hit single with Please Don’t Touch and tour after tour sold right the fuck out, sweaty, gurning fans packing in like epileptic sardines to see their grebo heroes turn hearing to shit and fracture necks.

Yet by the time Robbo got his (mutually understood) marching papers, Motörhead had lost a good 50 per cent of that audience, their money had evaporated into the ether of stage shows, touring and creative accounting, the band consisted only of Lemmy and Philthy and their last album had, comparatively, tanked.

As hard as this is for anyone to imagine, a whisper started floating around that Motörhead might be over, that they might break up. This was Motörhead in December 1983. Merry fucking Christmas and more figgy pudding.

But at the start of a new year, the band would announce the arrival of not one but two new guitarists: Phil Campbell and Michael Burston, aka Würzel. The new-look Motörhead would make its first public performance on The Young Ones – the cult alternative comedy show. And this would lead to a resurrection that Christ would’ve been proud of. Not even Orwell predicted this 1984…

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Motörhead

Having started rock'n'roll writing at the age of 15, Steffan Chirazi's career could almost look like an old Batman cartoon speech bubble! Sounds, Kerrang!, Bam, Rip and Spin are just a few of the publications he has contributed to over the years, and for the last 14 years he has been the editor of Metallica's own in-house publication, So What! magazine. He lives in San Francisco, CA with his family.