From rags to riches and back: The turbulent story of Bachman-Turner Overdrive

It took Randy Bachman four years to make his first million, and another four to lose it all, and more. This is the story of his band

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

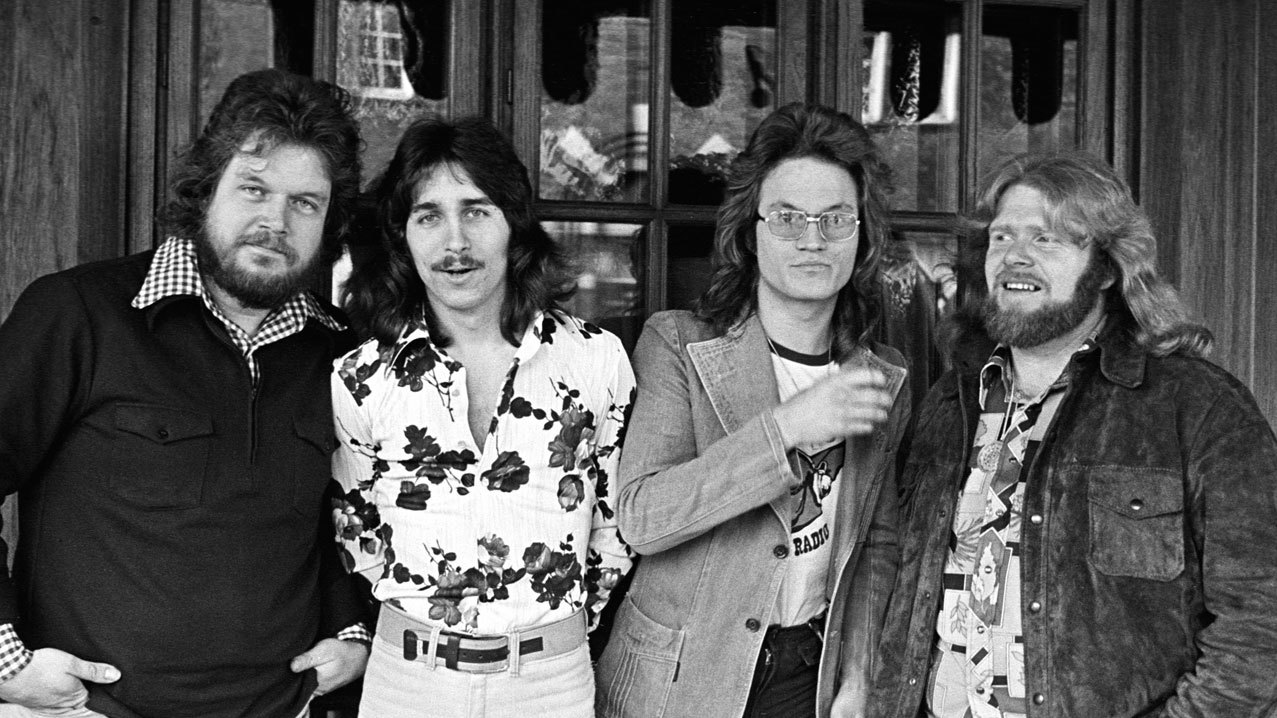

Randy Bachman was the lynchpin of a brace of Canadian supergroups in ‘American Woman’ hitmakers The Guess Who and, more meaningfully on this side of the Atlantic, 70s giants Bachman-Turner Overdrive. But the highs he enjoyed with those two bands have been more than matched by some dismal lows.

From being worth roughly $10 million, reflecting his position among the élite of Canadian musicians, he found himself $1 million in debt in autumn 1982 after a bitter divorce and custody battle. In the words of his autobiography: “It had taken me four years with BTO to become a millionaire and just four short years to lose it all – plus more”.

He was almost literally down and out in Vancouver, eating a burger from McDonald’s on a bench where tramps sometimes begged for change, when he was accosted by a fan. “Hey, aren’t you Randy Bachman?” was a greeting he’d heard many times before, but never in this situation. Couldn’t the guy just go away? Fortunately this wasn’t just a fan, he was also a loans officer at the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.

What transpired was that by putting up his future song-publishing income, Bachman obtained $30,000 that became a down payment on a house and helped him resolve his financial situation. With that sum his personal troubles may have eased, but BTO was and remains a bitterly divided organisation with founder, producer, writer and guiding light Randy [he financed the group, investing his life savings in recording their first album in 1972] on one side, and Fred Turner, Robbie Bachman and Blair Thornton, who still tour as BTO, on the other.

Although new material has been written and recorded, the crowds at the festivals, biker balls and rib roasts BTO play still want to hear the radio hits – the majority written by the now absent Randy. As you would expect, Bachman’s co-biographer John Einarson has no doubt where the blame lies: “The bottom line is that BTO was Randy’s vehicle, and the others were merely along for a very lucrative ride, and now want to bite the hand that fed them.”

From the opposite standpoint, Fred Turner believes that Randy’s inability to halt the band before it burned out killed the golden goose. The irony is that Bachman-Turner Overdrive was conceived due to another, equally bitter feud. Einarson: “Randy’s sole motivation in turning BTO into a success [and they were a huge success, far surpassing The Guess Who] was to prove to Guess Who singer Burton Cummings that he was wrong when he publicly declared Randy would never make it in the music business. Burton had to eat those words.”

The Guess Who may have passed you by, but for Canadians they were the first rock band to break big in the States – the equivalent of Scotland’s football team putting one over England at the old Wembley. [Other US Top 10 hits for The Guess Who included These Eyes, No Time and Laughing]. The band certainly didn’t evade the notice of the then teenage Lenny Kravitz, who covered American Woman to great effect in 1999 on the Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me soundtrack. But, as already hinted, the Guess Who story ended in tears. And it wasn’t helped, their producer Jack Richardson revealed, by Bachman’s conversion to the Mormon faith:

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Randy tried to impose his mores on the rest of the band, and with rock’n’rollers that’s the wrong approach to take, especially guys like Burton [Cummings] and [bassist] Jim Kale. They were stars by then, and enjoying everything that came with that. Randy was a much more reserved person, and the others certainly were not.”

That took its toll, health-wise, on Bachman – who, with American Woman at the top of the US chart in March 1970, was touring seven days a week – when gall- bladder problems should have led to him being hospitalised. It all came to a head with a prestigious Fillmore East showcase on the horizon, when the remaining members hired teen prodigy Bob Sabellico to play Bachman’s licks. Whether Bachman was sacked or resigned has never been established beyond doubt, but his bandmates – who regarded his doing a solo album and friendships with other musicians as threats to their livelihood – were unwilling to have him back.

Once back to full health Randy kept a low profile, producing several Canadian artists and sitting in on a televised country music variety show called My Kind Of Country. Backstage one day he bumped into fellow ex-Guess Who member Chad Allan, with whom he ended up forming a country rock band called Neil Young [who secured them a contract with Reprise], Brave Belt were arguably ahead of their time, given The Eagles’ later success. But after their two albums failed to sell, Bachman found himself back at the start line once more.

He believed his decision to walk away from The Guess Who had branded him both “a lunatic and a loser. Nobody wanted to work with me,” he moaned, “so I looked to my family.” He already had younger sibling Robbie on drums, while other brothers Tim came in on guitar and Gary managed the band.

But lead singer Allan left and, at Neil Young’s suggestion, Randy turned to CF ‘Fred’ Turner, a musician from the same Winnipeg background as both Young and The Guess Who, “Neil and my brother Gary said we really needed a strong lead singer,” Randy says. “Why not look at Fred Turner? He had this huge, what we call ‘Harley Davidson’ voice, a John Fogerty kind of thing”.

Equally importantly, Turner was married, didn’t do drugs and was a settled working musician. “If I had been a great guitar player or a great singer but crazy, I would never have had the opportunity,” Turner candidly admits. “Compatibility was important. Randy and I knew each other, but over the years we’d both been too busy to get out to see each other play.” [Interestingly, Bachman biographer Einarson believes Reprise executive Mo Ostin was the man to suggest a new singer, and that Neil Young didn’t actually know Fred Turner. Whatever the truth, a two-CD compilation on Bullseye Records is worth hearing to understand Brave Belt’s place in BTO’s evolution].

The moment that Brave Belt became Bachman-Turner Overdrive, or BTO, came at a university gig in sleepy Thunder Bay, Ontario. Chad Allan had left the previous week, but the band were still playing his country- flavoured songs to rapidly diminishing audiences. The promoter, disheartened, decided to sack them and bring in a replacement act from Toronto – “a rocking Brave Belt. Strongly influenced by the likes of Buffalo Springfield, Poco and fellow Canadian band” – for the Saturday night. But when this proved impossible he begged Brave Belt to stick around and play a set of classic rock covers. The university hall later resounded to Proud Mary, Brown Sugar, The Kids Are Alright, All Right Now and others, the dancefloor filled up, and a new band was born.

“We instantly saw the difference between playing sit-down music people could talk over and playing music they would jump out of their seats and dance to,” Bachman said.

For his part, Fred Turner more than approved of the change: “I was very happy with my situation; the alternatives were pumpin’ gas or selling shoes, which wasn’t what I was striving for. I think I brought a hard edge to the band; it was pretty countryish when I joined”.

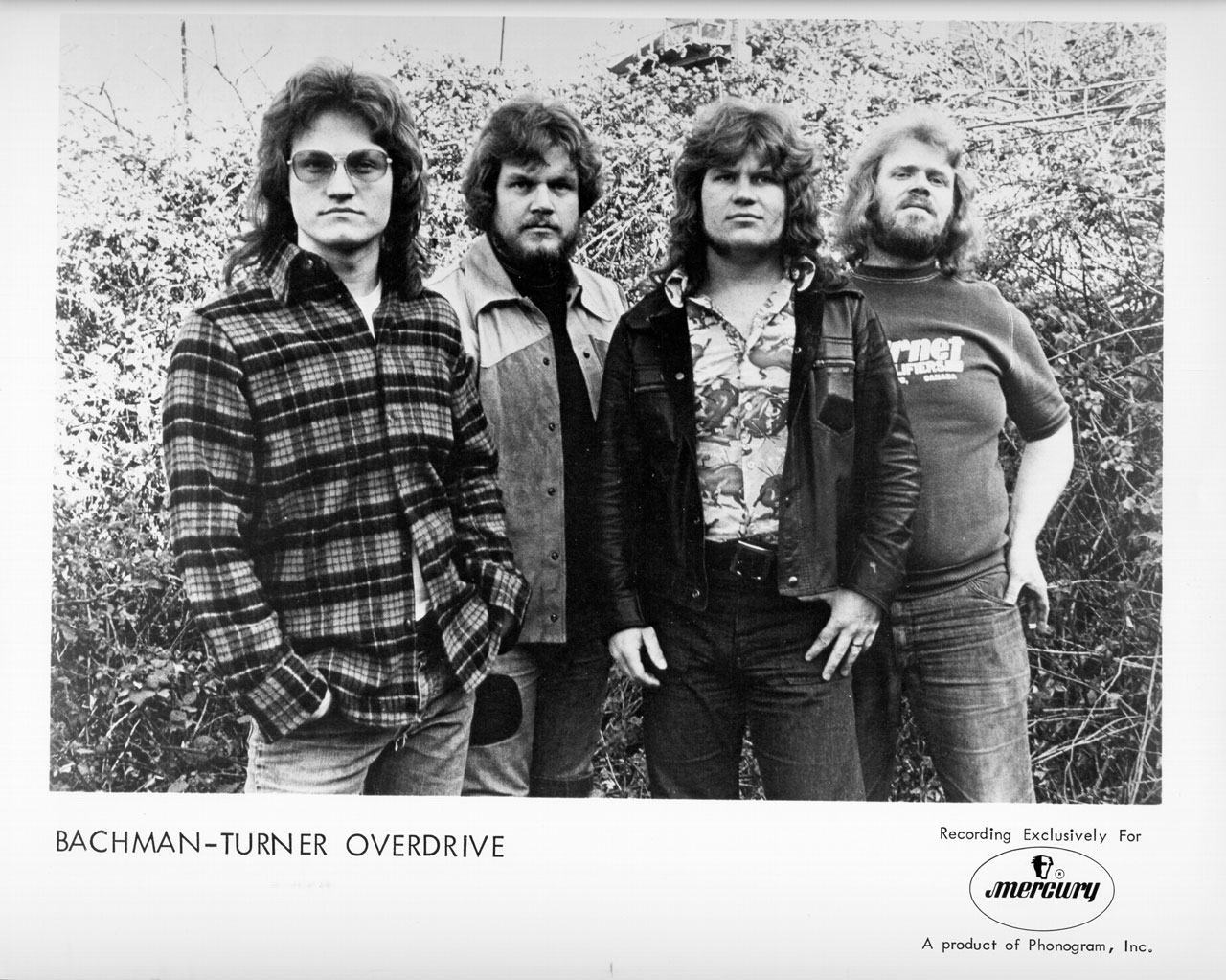

Moving to Vancouver on the west coast of Canada from their native Winnipeg, BTO parted company with Gary Bachman but acquired a new manager in Bruce Allen [later to manage Bryan Adams], whose dynamism would prove infectious. But nobody wanted the album Randy had already ploughed $97,000 into [his savings from The Guess Who]. Fortunately, Mercury had just lost Uriah Heep and Rod Stewart, and executive Charlie Fach heard BTO’s potential to fill at least some of that gap.

Sending them back to remix the album with more prominent guitars and add two new, heavier tracks reflecting the current musical policy, 1973’s Bachman Turner Overdrive was born. Interestingly, Mercury had already passed on the band and gone for The New York Dolls instead. BTO and the Dolls couldn’t have been more different. BTO was red-blooded blue-collar rock for the working man to sing along to [think ZZ Top, the by now disbanded Creedence, Doobie Brothers, Grand Funk], not drug-fuelled, lipstick- smeared, over-the-top glam posing.

The BTO ‘gearwheel’ logo conceived at this time has led to the band’s followers adopting the name Gearheads – also connected to the fact that their music is ideal for driving to. And driving was something BTO did a lot of in those early days, following up the record’s radio success with gig after gig. This was pre-MTV, remember [which may have done them a favour, as BTO were anything but photogenic], and like Status Quo, Rory Gallagher and Foghat and others they hung their hat on the consistency of their live performance. But BTO’s relentless schedule led to mayhem in the band members’ family lives. Randy’s wife and children followed him to Vancouver in a mobile home, but saw precious little of him while he was making his second chance count with week after relentless week of gigs.

Brother Tim later stated that he’d seen his year-old son for a matter of some three days, so having made that sacrifice he was bitterly disappointed to be sacrificed himself after the recording of Bachman Turner Overdrive II.

Musically, Randy would later claim he had recorded all the guitar tracks in the studio, and even corrected Robbie’s drumming when it had speeded up. Musical problems he could deal with, but jeopardising the future of the band through drink and/or drugs was unforgivable. Randy remains unapologetic, arguing passionately to Classic Rock that his way was the right way.

“When you’re the oldest brother you become an adult even though you’re a child,” he reasons. “When you’re looking after two or three younger siblings you have to say: ‘You can’t run away from me, you have to hold hands; you can’t run across the street…’. I sat all the band down, including my brother, and said: ‘When we’re on the road I don’t want any smoking, drinking or drugs. You can save it all, get drunk every night at home. These are my rules. Will you keep them and will you sign this piece of paper?’ Everyone says yes. Two years, three years later, everyone’s a millionaire and they stop keeping the rules.

“It’s the old John Lennon thing,” he argues of the USA’s then prevalent drug paranoia. “You get busted with one joint, and the American government will not give you, a Canadian, a green card to work there again. Now, ninety-nine per cent of the money a band makes is from the US – more record sales, more tours, more people, more gigs. I can’t have you jeopardise that. I don’t want to be arrested, have the police break down my door and strip-search me at the border because you’ve got some stupid thing in your suitcase.

“They were all greenhorns,” Randy now says of his bandmates. “I took them out of school, paid them a salary, and in a couple of years everyone had millions in the bank, sold millions of records and thought they knew something. I knew the route back to the top again, I didn’t want to take nine or 10 years to get there. So many times I’ve left people behind – literally. Say we’re leaving at 10 o’clock and at 10 they’re not ready. Well, you know where the next gig is, we’re going!”

This seemingly cold-blooded single-mindedness would have repercussions further down the line, but it appeared to have paid off in spades when BTO’s Not Fragile became one of the landmark rock albums of 74. And the key track [You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet] was the one that broke them in the UK. The addition of guitarist Blair Thornton from Vancouver band Crosstown Bus in place of Tim Bachman gave them a lead player and a good-looking co- frontman [deflecting a little from Guess Who man Burton Cummings’ sniping description of them as ‘Bachman-Turner Overweight’]. But Not Fragile – its title a deliberate riposte to the then-recent Yes album Fragile [“They were delicate and symphonic, we were the exact opposite,” Randy says] – took BTO out of The Guess Who’s league and put them among the big hitters of North American rock.

Thornton had a different guitar style to Randy’s, a fact for which Bachman was grateful: “He was known for playing in the Eric Clapton/Bluesbreakers style, and was more advanced on the guitar than my brother Tim, who was basically a rhythm player who left all the lead to me. I’m not that good. I would repeat myself, my vocabulary is limited and I didn’t have time to go out and learn. So Blair brought in a new style. We now had twin lead guitars, and that made my job a lot easier; it gave us more versatility.”

You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet had a jangling guitar intro reminiscent of the band’s first US hit, Let It Ride, but went on to establish its individuality thanks to the stuttering delivery of the lyric. While some assumed this a parody of Roger Daltrey’s ‘Why don’t you all f-f-f-fade away’, it was actually a jokey dig at former manager brother Gary from his elder sibling. But Randy never thought it would make an album track, let alone a single, until Mercury’s Charlie Fach once more recognised its potential.

“Our engineer suggested we play Charlie the work track, a stuttering song we cut at the start of the sessions while we were getting our sound balance. The minute he heard the intro chords he yelled: ‘This is a hit!’. The album was all done, he had arrived to hear the final mix, and now he wanted us to add this silly track!”

Boston, Portland, Texas, LA, San Francisco… all over the USA, stations were picking up on the song; Randy couldn’t listen to it on his radio without switching it off in embarrassment. It not only became BTO’s sole million-selling single, it also helped the album it was on to rack up sales of three and a half million. Not Fragile rocketed to the top of the US album chart, eclipsing to No.18 position achieved by ‘Bachman-Turner Overdrive II’ and the first album’s No.48 [although both were million sellers]. All three albums had been recorded and released in one hectic 18- month period, which was testimony to Randy’s unrelenting work ethic. The fact that Bachman had sung the big hits – Takin’ Care Of Business and You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet – put Fred Turner in the shade somewhat. Also significant was that the band didn’t tour their home country until 1975, delighting fans there but also provoking a press backlash that suggested they hadn’t shown their Canadian roots enough respect, and had deserted their homeland to chase the mighty US dollar.

Randy and his manager responded aggressively, and the result was negative headlines. Combined with the comparative failure of fourth album Four Wheel Drive in 1975 – which sold half-a-million, and suggested they’d flooded the market – the seeds of decline had been sown. Hey You, the album’s hit single, failed to emulate …Nothing Yet – indeed it peaked short of the Top 20. Randy admitted it was directed squarely at Burton Cummings, an ‘eat shit’ statement, albeit a poorly timed one: “I deserved to gloat a bit after all the mud Burton had slung at me.” While The Guess Who’s impact had been negligible in Britain, reaction to a BTO tour following You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet was “phenomenal – everyone loved that song”.

Gigs in Ireland, Wales, Scotland and all over England pulled in a virtually all-male audience, unlike those BTO had drawn in North America.

“We went to Edinburgh to play a theatre of 2,400 people, and there’d be just one or two girls there. They called it ‘guy rock’,” Randy recalls. Then as You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet lived up to its lyric and hit No.1 in 20 countries, they took Thin Lizzy with them to open shows in Germany, Holland and then back to the States. The link with strait-laced, clean-living Randy and the fatally hedonistic Lizzy leader Phil Lynott was unlikely but effective.

“I loved the twin guitars, I loved Phil and his Hendrix look,” Randy says. “Lizzy were just opening in England, but our label wanted to bust them in the rest of Europe and break them wide open in the States. So we toured with Phil and the boys for seven or eight months.”

BTO’s 1976 album Head On was notable mainly for the guest appearance of Little Richard. The single Looking Out For Number 1 has been used by Bachman’s critics to suggest his personal philosophy, but its jazzy flavour suggested he was bored with the successful formula. And the fact that the label rushed out The Best Of BTO (So Far) shortly afterward suggested that they too thought that BTO had run their brief but very profitable course.

Randy Bachman started playing the role Jon Bon Jovi would take on with Skid Row, discovering bands and extending his production company to work with them, the most notable of these being Trooper. But that relationship ended acrimoniously, and a song from them called Go Ahead And Sue Me presaged bitter legal wrangles to come for BTO themselves.

“All things are destined to end,” Randy says, “but I think we could have prolonged it. I got so big-headed with suddenly having the number one album and single again, you don’t look at the downside of anything. When the label calls you up and says: ‘Wow, you’re hot. Do another album’, you don’t say give me six months, 12 months off to have some new experiences to write about. We just went in and did another album. And guess what? The album went double platinum.

“When we did Four Wheel Drive,” Bachman continues, hitting his stride, “we basically started to repeat ourselves. You notice there’s a sameness in ‘Hey You’ that there is in You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet; there’s the sameness in Flatbroke Love that there is in Not Fragile. That came from Fred Turner. Instead of using other people’s influences – Ritchie Blackmore, Black Sabbath, The Beatles or whatever – and making them our own, we didn’t have time to do that. We started copying ourselves, and that’s very dangerous.”

What’s more, Bachman’s position as chief songwriter was under threat. “Suddenly guys who aren’t, quote, ‘the main songwriters’ all want a song on the album – or, worse than that, want equality. There’s 12 songs, they each want three, and they bring three songs to rehearsal. While for my three I bring 15 songs. Because I’m a songwriter. For my songs we pick three great ones. For their three they pick three mediocre songs, and it waters down the process.”

In musical terms the crunch came in 1977 with Freeways. The band were in the position where diversifying musically might lose them fans, but continuing as they were would see them become whipping boys [as, for example, Status Quo would find in the following decade]. The Rolling Stones embraced disco with Miss You; blue-collar rockers The Doobie Brothers took on board brilliant singer Michael McDonald and reinvented themselves with the Takin’ It To The Streets album and, later, the US chart-topping single What A Fool Believes. Bachman-Turner Overdrive failed to work that same alchemy, and the imbalance of creative input and financial reward turned internal dissension into a fatal malaise. All in all it spelled the beginning of the end for Randy Bachman and the band he had founded.

BTO’s final album, Freeways, remains a major debating point among Gearheads. Manager Bruce Allen believed that Randy already wanted to launch a solo career less dependent on the roadwork that kept him away from his family and his luxury $3 million mansion at Lynden, just across the Canadian/US border in Washington state.

Whatever, Fred Turner’s verdict on hearing the finished record – sequenced, as usual, without the band’s input – was simple: “This doesn’t sound like BTO. So what’s the point in carrying on?” Turner now maintains: “I always wanted to take it slower… Randy had signed his company to Mercury Records and signed the band to his company, since he was funding the whole thing. Everything went on his and Mercury’s timetable. It finally came to a head for Freeways when Blair, Rob and myself told Randy that we were burnt out, didn’t like the songs we were writing, didn’t like the songs he was writing, and that we wanted to take some time to regroup – especially since all the other bands were taking a year or two between albums, not doing two a year like we were. Randy told us that his songs were fine, and forced doing the album. It ended that version of the band.”

Bachman conceded that Freeways was “kinda the end. Looking at it now, we should have taken four, five, six months off, everyone go fishing, play with their kids and wives, guns and boats, live a little, and then come back together with new ideas. In retrospect, that’s what a lot of great bands do. And we didn’t.

“It happened, it was great, and I’m grateful for it. We sold a lot of records, we did it in a third of the time it took The Guess Who to do it. I got divorced because the work with BTO was so extensive – 300 days a year, three years in a row; I just wasn’t home. I was hell-bent on making it, as good or bigger than The Guess Who. And we did! But when you have your sights set like that, you’re looking so far ahead you’ve lost your peripheral vision, your contact with everything around you. You’re bulldozing, steamrollering ahead. You get there, say ‘I’m here!’, look around, and it’s not as great as you thought. Once you hit number one there’s nowhere else to go but down.”

Bachman does, however, believe the Freeways album has merit, citing Down, Down, Shotgun Rider and My Wheels Won’t Turn as highlights.

“Blair Thornton played a phenomenal solo on …Wheels that was very Allman Brothers. We were trying different things. It was still BTO, yet we had strings in one song. Everything was changing in music in the late 70s. You either change or die; you shoot for the target and you either hit or miss. I went up to bat, swung, and struck out. But before that I hit many home runs.”

Randy Bachman left Bachman-Turner Overdrive early in 1977, the last TV show he did with the band being on New Year’s Eve 76. The remaining trio brought in bass player/songwriter Jim Clench from April Wine and Fred Turner moved to guitar. Manager Bruce Allen, once Randy’s fellow taskmaster, remained with the band, who now called themselves simply BTO. Although neither Street Action [1978] nor Rock And Roll Nights [1979] was a hit, the latter inspired a sold-out, 80-date North American tour in the spring. Nevertheless they disbanded later that year.

Jim Clench worked on Bryan Adams’ first album in 1980, then after a decade as a session man returned to April Wine. Meanwhile, there was plenty of ferment in the Bachman family. Having failed to cut it as a solo artist, Randy formed Ironhorse. But one absence on the road too many led to his first wife filing for divorce. The bitter two-year battle that followed saw him lose the majority of the wealth he had worked so hard to amass since The Guess Who split. A less likely reunion came in 1981 with the Union album, which saw him join again with Fred Turner, but with Randy unable to tour in the midst of his custody battle it was not to be.

With the aforementioned Vancouver bench experience having put Bachman back on an even keel financially, he used a Guess Who reunion the following year to help pay the mortgage of the house he’d bought with new love Denise. The creative spark between Randy and Burton Cummings was again evident, but so was the antipathy, and a live album was the only fruit of that reunion. Ironically, just as Randy had let the BTO acronym and logo leave his hands, he was also to find that bass player Jim Kale had trademarked the Guess Who name, denying him any claims on the first group he co-founded.

This had scuppered attempts by Bruce Allen to relaunch The Guess Who in the US. As road manager Jim Martin said: “Kale’s clone band hurt the name. Promoters said: ‘Why the hell do I want to book this band called The Guess Who when I’ve got them down the street at a bar for two grand?’”

With that avenue blocked, it was only a matter of time until Randy and Fred Turner buried the hatchet once again and reunited, in 83. Robbie Bachman had been asked to play drums but declined, and was replaced by Garry Peterson who switched horses from The Guess Who [a belated change of heart from Robbie led to yet more sibling aggravation], while brother Tim now had the satisfaction of replacing his own one-time replacement in BTO, Blair Thornton. Golden-eared A&R man Charlie Fach was now at a new indie label, Compleat Records.

The music business was a different ball game from this perspective, and an eponymous studio album failed to get decent distribution. Nevertheless, their luck seemed to have turned when the ‘new’ band were asked to open for Van Halen on a US tour, newly arrived VH vocalist Sammy Hagar being a long-time BTO fan. This stroke of luck seemingly set things fair for the future. But yet again fate played a hand: Fred Turner was unavailable. And while the band battled through in a trio format with judicious use of backing tapes, another member of the ‘classic’ line-up was now disenfranchised.

Interviewed at the time, Tim Bachman was overcome by the audience response: “I would say 1986 for both Van Halen and BTO has been the best year on the road in any of our careers, as far as playing with people who you like and enjoy and having a great time together”.

- Black Oak Arkansas: the band who had it all, then gave it all away

- 10 of the best rock bands from Canada

- Story Behind The Song: You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet by Bachman Turner Overdrive

- How The Guess Who's American Woman was written by accident

An in-concert album Live Live Live was rushed out to capitalise on the BTO/VH phenomenon, but yet more internal feuding resulted when Garry Peterson, who broke his ankle playing ice hockey, was thrown off the tour.

“I received a call from Tim saying: ‘We no longer require you in the band’. How do you think that made me feel? I lost my house because I didn’t have any income. I’d left Burton [Cummings] to join BTO, and he never forgave me for that.”

Cummings cropped up again when, without fanfare or publicity, he bought the publishing rights to The Guess Who songs he’d co-written with Randy. This put a spoke in a proposed Bachman-Cummings duo tour because, far from bolstering this joint venture, it ended in a court case and much bad feeling. But Bachman, while still smarting, hasn’t let this become a reason for him not to join in sporadic reunions of The Guess Who, who last year opened for The Rolling Stones in the Toronto SARS virus benefit concert [2003].

The members of the mid-80s BTO dropped out one by one except for Tim Bachman, who remained with three younger musicians as manager and performer of an outfit further removed than ever from the ‘classic’ band. The original BTO reconvened, at Bruce Allen’s suggestion, from 1988 to 1991, Randy almost inevitably the man to bail out. Biographer Einarson suggests “he wanted to record but the others weren’t ready”, while Turner cites his unwillingness to play the oldies:

“He realised that people were only interested in hearing the 70s hits, so he decided to leave again.

“We wished him well and told him we would only use the short version of the name he had sold us back in the 70s to carry on working, and would only bill it Bachman-Turner Overdrive if he returned to the stage with us. He started his own band called Bachman, with a set of wings and a gear behind the name. Seeing what he was doing, we contacted him, his lawyer and record company to inform them that we thought there was an infringement in trademarks happening. The record company asked Randy to change the gear, which became a disc instead. And then Randy sued us for damaging his business. From then on there were more lawsuits that lasted for 10 years.”

As for the current stand-off situation, Randy admits: “I do regret it. I’m the eldest brother and Rob, the drummer, is the youngest brother. There’s some ‘bee in his bonnet’, that’s the best way I can put it. We were asked to be in the [Canadian] Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame at the 2003 Juno Awards, and I said that would be no problem. He said he didn’t want us to play on stage together as it would cause confusion. He’s still touring as BTO, with another guy named Randy [Murray] on guitar, and thought it would be confusing if I played at the Hall Of Fame; it would spoil the momentum with the other guy.”

Turner’s take on the refusal is that “we are happy working on our own and don’t want to muddy the water again”. So although he’s finally made peace with The Guess Who, BTO remains a tantalisingly out-of-reach part of Randy Bachman’s musical past. Not that he doesn’t try to reclaim it once in a while:

“The best response I get when I tour with The Guess Who is when, every fourth or fifth song, I go into a BTO number and the crowd goes mad. I do Let It Ride or Four Wheel Drive or You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet or Takin’ Care Of Business and the crowd absolutely love it, because it’s a big-up, pounding, bang-your-head moment. Only American Woman of The Guess Who repertoire has that.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 66.

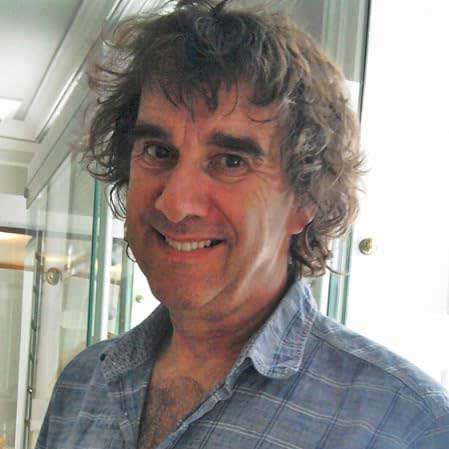

Michael Heatley is the author or editor of over thirty biographies, including Bon Jovi: In Their Own Words, The Complete Deep Purple and Dave Grohl: Nothing to Lose. Since 1977 he has written more than a hundred music, sport and TV books.