The Secret History Of Toto

From drug busts and tragic deaths to Michael Jackson, this is the untold and often unbelievable story of the AOR legends

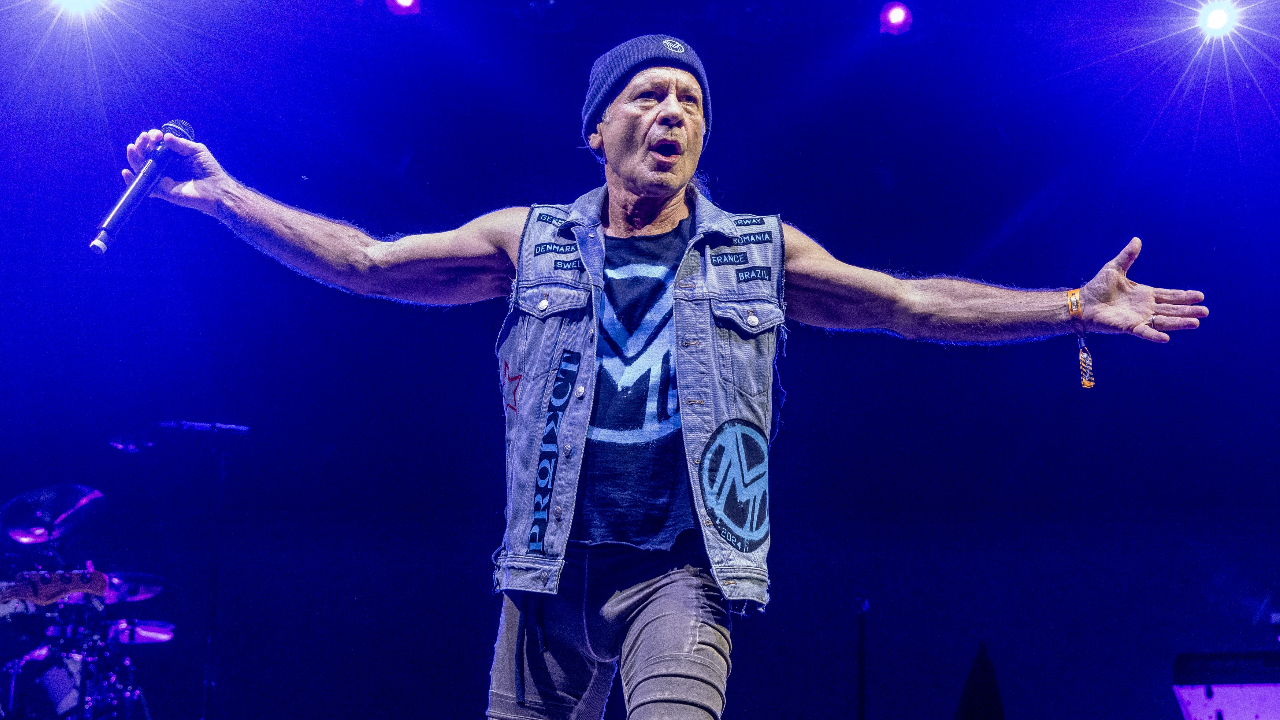

March 3, 2015. Toto guitarist Steve Lukather is speaking to Classic Rock via Skype from a hotel room in Santiago, Chile. Lukather is in South America during a tour with the other group he plays for, Ringo Starr’s All Starr Band. It’s 9am – early for many rock stars, but not for a guy who quit drinking alcohol eight years ago.

During a two-hour conversation, Lukather talks fast, laughing a lot, swearing a lot, bouncing around on the bed where he sits. He’s buzzing about the new Toto album, their first in 10 years, its title, Toto XIV, an echo of their multimillion-selling hit from 1982, Toto IV. He also stresses the significance in this being the first Toto album in 27 years to feature co-founder Steve Porcaro as a full member of the band. “It’s important that there’s a Porcaro in Toto,” Lukather says. But in that moment his mood suddenly changes.

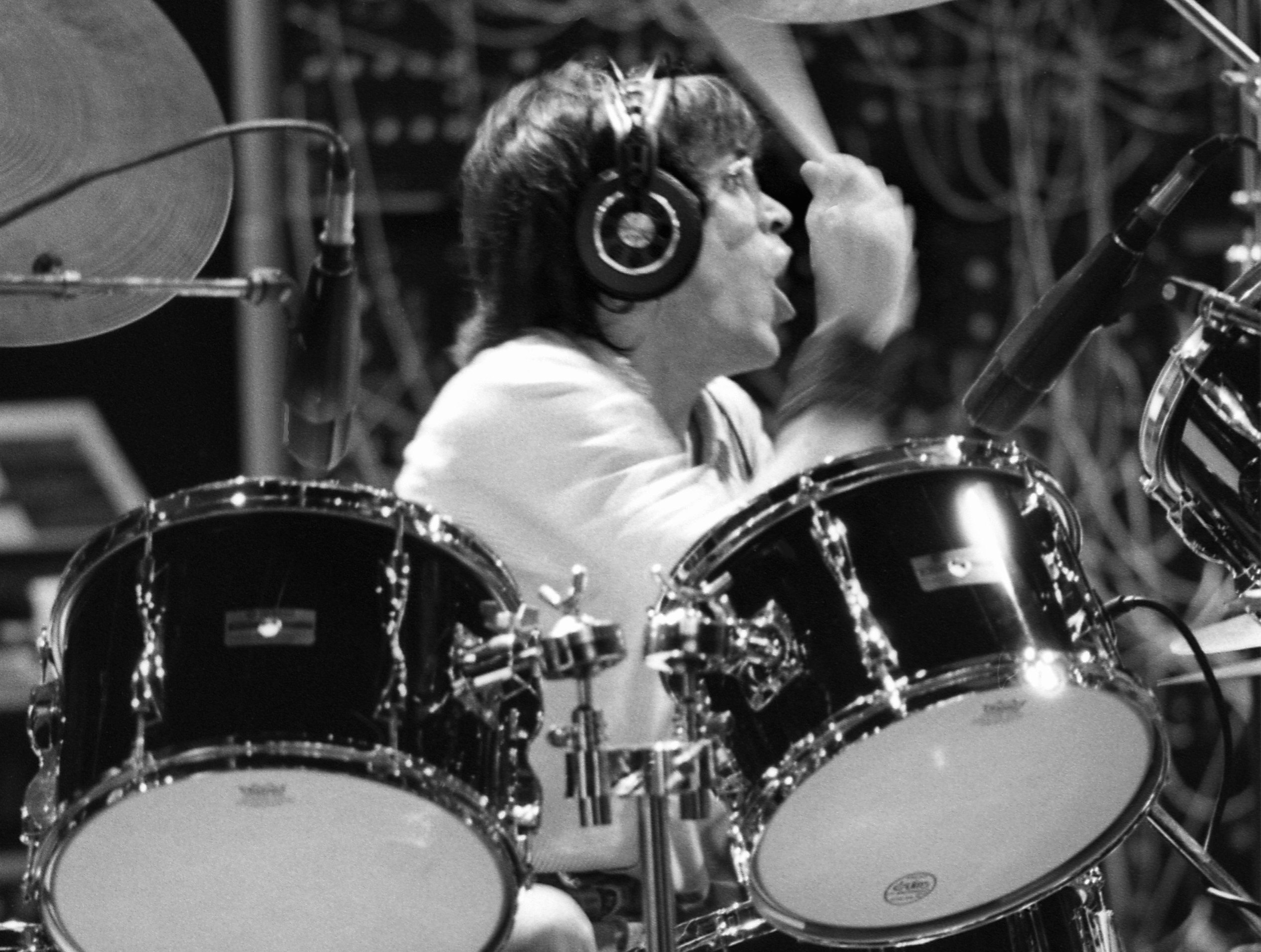

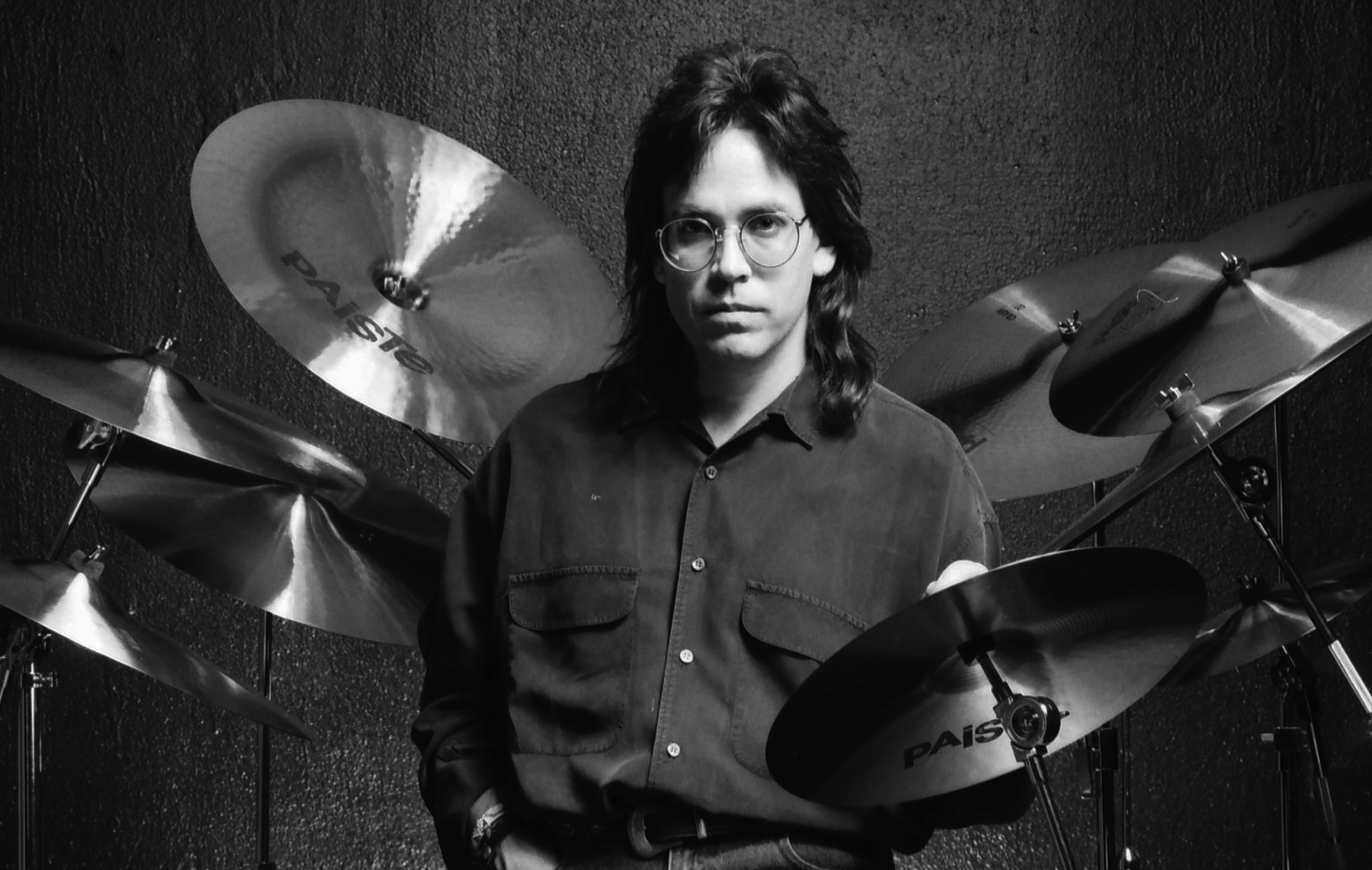

The Porcaro family is central to the story of Toto. When the band formed in Los Angeles in 1977, Jeff Porcaro, the eldest of three brothers, was the drummer and de facto leader; Steve, the youngest, played keyboards. In 1982 Michael Porcaro joined as bassist. But in the years that followed, the family has endured the worst of times. In 1992 Jeff Porcaro died of a heart attack at the age of 38. In 2007 Mike Porcaro was diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a motor neurone disease that causes muscle wasting, resulting in difficulty with speech and eating and then breathing. Forced by this condition to withdraw from the band, Mike slowly deteriorated in health for eight years, with no hope of recovery.

When Steve Lukather speaks from Santiago, Mike Porcaro is in the final stages of his long battle with ALS. Five days previously, Steve Porcaro had described the situation in bleak terms, wishing for an end to his brother’s suffering. “It’s a nightmare,” he said. “We’re hoping it’s going to be over soon.”

What Lukather reveals, in a quiet and hesitant voice, is the nature of that suffering. “ALS is the most cruel, insidious disease,” he says. “It’s so hard to watch someone just melt away, to become a prisoner in his own body. In his brain he’s alive, but it’s hard for him to take a breath. He can’t eat, can’t move. Every time I see him, the last thing I do is kiss him, and we cry together…”

With this, Lukather leans forward, put his head in his hands and weeps. After a long silence he looks up and swallows hard. “Two brothers from the same family,” he says. “It’s so random, and you think: why is this happening to this family? They’re the nicest people. There’s a lot of cruelty in the world.”

Less than two weeks later, on March 15, the death of Mike Porcaro was announced in a statement from Steve Porcaro: “Our brother Mike passed away peacefully in his sleep… surrounded by his family.” It was followed by a tribute from Steve Lukather: “My brother Mike Porcaro is now at peace. I will miss him more than I can put into words.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

For Toto keyboard player David Paich, now 60, the period in the early 80s when everything seemed so easy for Toto seems such a long time ago. A time when, as Paich recalls: “We thought we were absolutely bulletproof.”

In a golden age for the music industry, it was Toto IV that transformed the band into one of the biggest in the world. That album’s slick sound – an immaculately crafted blend of AOR, progressive rock, light funk and soul – had been slammed by Rolling Stone magazine as the epitome of bland, synthetic corporate rock. But it went on to sell five million copies in the US, yielding the No.1 single Africa and the No.2 hit Rosanna.

At the same time, the members of Toto were also making serious money as writers and session players on hit records by a variety other artists – most notably on the album that would become the biggest in the history of popular music: Michael Jackson’s Thriller. When it came to making hits, Toto just couldn’t miss. And yet, even at the height of this success, and the opposite of the smooth harmony in the music, it was a band fraught with tension.

They fought over the music. “We were all very strong personalities,” says Lukather, who describes the making of Toto’s albums as “like five horny bulls in a pen with one cow – the cow being the recording machine”. They fought over whose songs were released as singles. Paich, author of Africa, Rosanna and the band’s first hit, Hold The Line, laughingly recalls: “The other guys were always trying to write ‘The Single’. I had an abundance of them.” There was also a sibling rivalry between the Porcaro brothers, in which alpha male Jeff had the domineering presence of a drill sergeant. With success came inflated egos. And, adding to a combustible mix, there was cocaine, the drug of choice for all high-rolling rock stars of the era.

After the heady peak of 1983, there was for Toto an inexorable descent in the latter half of that decade and beyond. There were struggles both professional and personal: a failure to repeat the success of Toto IV; the firing of original lead singer Bobby Kimball following a drug bust, and the difficulty in replacing him; the pressures of balancing family lives with the demands of a touring rock group. Above all there was the death of Jeff Porcaro, sudden, unexpected and devastating.

“We’ve been through the highest highs and the lowest lows,” Lukather says. “Death, drugs, divorce, success, failure, critics hating us, singers leaving. But no matter how many times they’ve dragged us out to the gallows pole, this band will not die. Something keeps dragging us back.”

Today Toto is comprised of four key members: Lukather, Paich, Steve Porcaro and Joseph Williams, the singer who first fronted the group in the late 80s. For the recording of Toto XIV, the line-up was completed by the return of another founding member, bassist David Hungate.

From the outset, Lukather makes clear the reason why there is a new Toto album in 2015: the band had a contractual obligation to do so. “Nobody likes being told what to do,” he admits. “But our lawyers said: ‘Why don’t you just make the fucking record? It’s a lot easier than fighting this and a hell of a lot less expensive.’”

Lukather is candid in his description of Toto XIV as an album “born out of litigation”. Despite this, it is a work of genuine depth and quality. “We’ve tried to make a classic Toto record,” he says. “And, really, there’s nobody that makes music the way we make it.”

- My First Love: Steve Lukather on the Beatles

- Toto: The Story Behind Rosanna

- The Outer Limits: Toto

- Toto’s Mike Porcaro dead at 59

In the Toto of 2015 there is a hierarchy within a hierarchy. Only Paich, Lukather, Porcaro and Williams are featured in current group photos, and it’s these four who speak to Classic Rock – separately and at length: Lukather from Santiago, the others from their homes in Los Angeles. And while Porcaro and Williams have important roles in the group, it’s Paich and Lukather who hold seniority: Paich as the co-founder of the group alongside Jeff Porcaro, and the writer of Toto’s biggest hits; Lukather, at 57, the sole constant in the entire history of the band.

In conversation, Paich has a quietly understated authority. Lukather is quite the opposite: outspoken, full of spicy anecdotes; the kind of person you’d want to sit next to at a dinner party. During the course of our interview, the guitarist refers to two vocal critics of Toto – singer John Mellencamp, and the late LA Times writer Robert Hilburn – as, respectively, “a douchebag” and “a cunt”. Wary of how this will look in print, Lukather adds: “Please don’t make me sound like an asshole. I just have a very colourful vocabulary.”

Joseph Williams, at 54, is the junior partner in this core quartet, and has the manner of one who knows his place. He is deferential to Paich and Lukather. He also knows how this band works. Like The Beatles and the Eagles, Toto has always had multiple lead vocalists. As Lukather notes: “I’ve sung on more hits than Bobby Kimball ever did.” Williams is aware of what it means to be the singer in Toto. It doesn’t make you Mick Jagger.

More surprising is what Steve Porcaro says about his position in the group. As a founding member – and as a Porcaro brother – his return to Toto is significant. But when he talks about his contribution to the band in its earlier days, he says repeatedly: “I felt undervalued.” This, he explains, was partly due to his role as second keyboard player to Paich. As a technophile with a keen understanding of cutting-edge synthesisers, Steve acted as programmer, but invariably it was Paich who cut the tracks in the studio. On a deeper level, his sense of his place within the band was affected by an uneasy relationship with his elder brother.

“Jeff and I were always at each other’s throats,” he says. “Mike got along with both of us. But Jeff and me really bumped heads. Jeff was the coolest, hippest older brother I could ever dream for. He could show me such warmth at times. But he was such a musician’s musician. It came so easily for him, and he expected that from everybody he worked with. And I wasn’t that kind of guy. Jeff had this thing about being ‘in the pocket’. If not: ‘Get the fuck out of here.’ There was definitely some brother shit going down, because I’d hear about him singing my praises when I wasn’t around.”

Jeff Porcaro’s shadow still hangs over Toto, 23 years after his death. On the band’s new album there’s a song dedicated to his memory: Unknown Soldier (For Jeffrey). Lukather says that he still thinks of Toto as Jeff Porcaro’s band. “Every time we’re on stage,” he says, “I feel Jeff is there with us.”

In the beginning it was Paich and Jeff Porcaro who were, in Paich’s words, “the co-leaders of Toto”. In Jeff’s absence, Lukather developed a greater influence on the band. “There was a void,” he says, “and I stepped up.” There was a brief period in the 2000s when Paich left the band. Lukather, however, has been ever-present. “I’m the only guy that’s been there from day one,” he says. “I stayed though the best and worst of times. I kept this thing alive – because I love this band.”

For a long time, Lukather has acted as Toto’s chief spokesman. And part of that job is to defend the band against the criticism that has stuck to them like glue throughout their career. “We were the whipping boys for the press,” he says. “We came out in the late seventies when punk music was brand new, and we were the antithesis of that. They called us ‘soulless’ because we were session musicians. They called us ‘faceless’ because we didn’t have an image or a pretty boy up front. We weren’t ‘real’, blah blah blah…”

In an industry in which image has always counted, Toto were terminally uncool with their bad hair, moustaches, geeky specs and – in the case of Paich and Kimball – sagging paunches. They were viewed as a bunch of spoilt rich kids who never had to pay their dues. And they were seen as archetypal LA cocaine cowboys. There’s some truth in all of this. But, as with so many aspects of Toto, the full story is more complex.

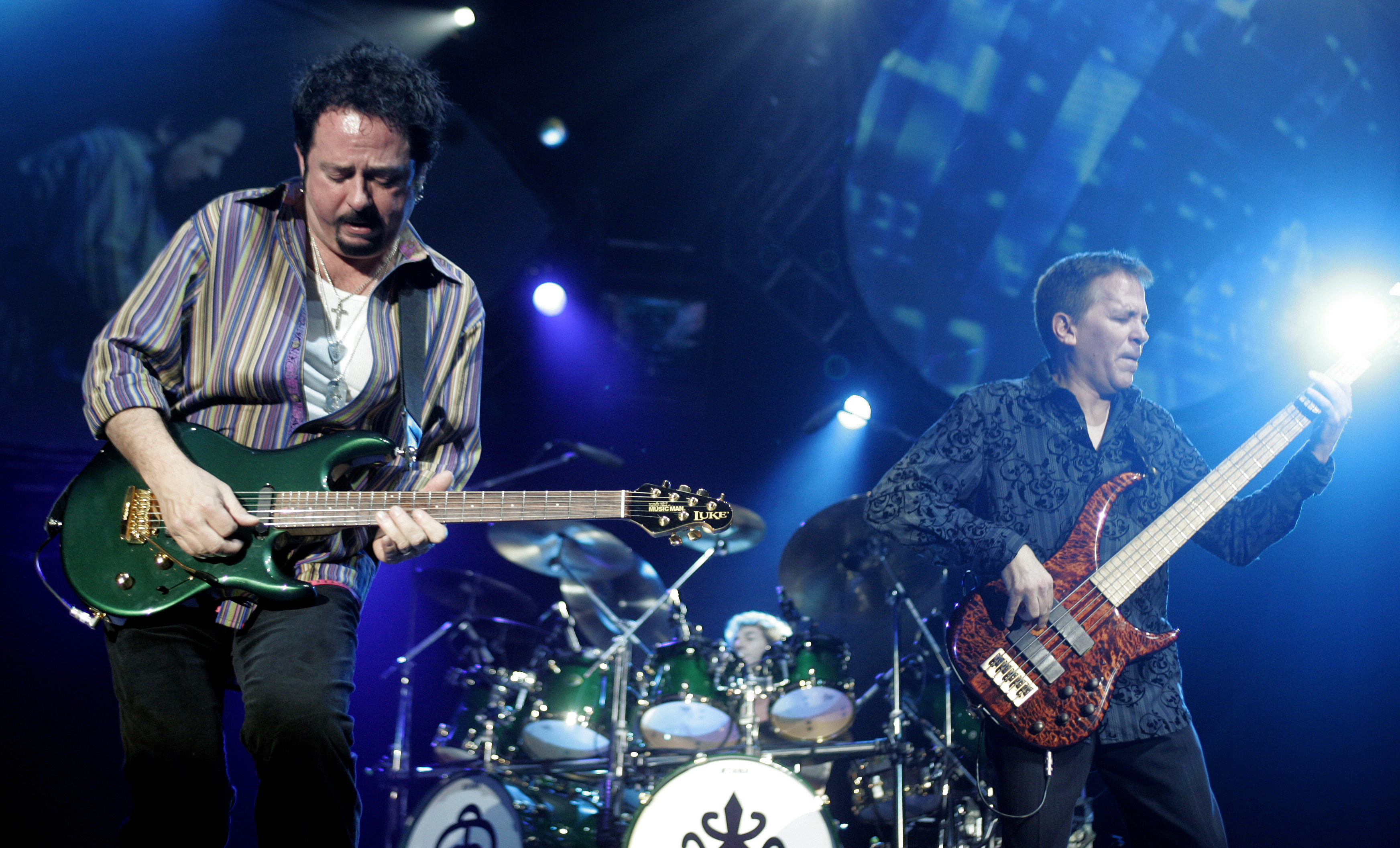

If ever a rock band was hard-wired for success it was Toto. By the time the band was formed in 1977 by Jeff Porcaro and David Paich, the two were already established session players, with Jeff having appeared on hit records by Steely Dan and Jackson Browne. Their big breakthrough came after Paich, Porcaro and their old high-school friend David Hungate played on Boz Scaggs’ s1976 album Silk Degrees. The trio were joined in Scaggs’s touring band by Steve Porcaro and his buddy Lukather. When Scaggs’s label, Columbia, discovered that this was a new group in the making, they offered them a contract. “Without an audition,” Steve says, “a record deal was thrown in our lap.”

According to Paich, the acquisition of a major-label contract was expected. Among the five young musicians was a confidence – a sense of entitlement, even – that said a lot about where they had come from. There is a lack of irony when Paich claims that they had “diverse backgrounds”. His father Marty was a successful composer; the Porcaros were the children of famous jazz drummer Joe Porcaro; Hungate’s father was a congressman, Lukather’s an assistant director in television. This was diversity only within the context of upper middle-class suburban LA.

Paich acknowledges that he and the Porcaros had a head start on other aspiring musicians. “Our fathers opened a few doors for us,” he admits. But he adds: “It’s not true that we’ve had things handed to us easily. We had to work hard.”

The new band’s sound was based primarily on heavy and progressive rock. “We loved Queen, Zeppelin, Yes, ELP,” Paich says. “We didn’t want to be the Eagles.” They found a powerful singer in Texas-born Bobby Kimball. The name for the group, as Lukather recalls it, came after Paich and Jeff Porcaro got stoned watching The Wizard Of Oz, in which the lead character had a dog called Toto.

It was with perfect timing that the band’s debut album, Toto, arrived in 1978. In an era when Adult Oriented Rock was a dominant force, Toto’s sound was perfect for radio. Paich recalls telling the record label: “This will go double-platinum for sure.” And it did, after Hold The Line reached the US Top 5.

“The first album’s success felt like a foregone conclusion,” Steve Porcaro says. “That was the cockiness of youth.” It all seemed too easy. Only then, as Porcaro says, “reality bit us in the ass.” Their second album, 1979’s Hydra, had an experimental prog rock style. It bombed. Likewise the third album, Turn Back, a more straightforward rock record. After two failures Toto were in danger of being dropped. Paich was informed by record company execs: “We want to see if you guys still know how to make hit records.” And he, more than anyone else, proved they could.

It was Paich’s songs that made Toto IV the biggest hit of the band’s career. Rosanna was named after the actress Rosanna Arquette, who was at the time dating Steve Porcaro. With its funky shuffle beat from Jeff Porcaro – in part inspired by Led Zeppelin’s Fool In The Rain – and an irresistible chorus, it was all over FM radio in the summer of ’82. Following that, Africa went to No.1. It was an unlikely hit song, with its unorthodox rhythmic structure, built around a drum loop from Jeff, and with a convoluted, quasi-mystical lyric from Paich, typified by the famous line: ‘Kilimanjaro rises like Olympus above the Serengeti.’ Paich says he ended up as lead vocalist on Africa because nobody else in the band could get the words out right.

At the same time as Toto IV was selling millions, so was Michael Jackson’s Thriller, an album on which the members of Toto were heavily involved. Steve Porcaro had worked as a synthesiser player and programmer on Jackson’s previous album, Off The Wall. For Thriller, Jackson’s producer Quincy Jones approached Toto for a rock song. Jackson had been looking for something like The Knack’s My Sharona. Instead, what he had discovered was a ballad written by Steve Porcaro: Human Nature. Having struggled to get his songs recorded by Toto, for Steve Porcaro this was the perfect validation. He was present when Jackson cut his vocal for the song. “It was amazing being in that room with Michael,” he says. “A guy at that level of artistry, and what he brought to that song.”

Jackson had eventually found his My Sharona in Beat It. The guitar solo on the track was by Eddie Van Halen, but it was Steve Lukather who played the riff, and the bass, and Jeff Porcaro who was on drums. David Paich played keyboards on various tracks on Thriller, including Billie Jean.

During this period the members of Toto were so ubiquitous on the LA studio scene that when the band won seven awards at the Grammys in 1983 there was a backlash in the media. “People said it was a fix,” Lukather says. “That we won all those awards because we knew everybody in the music business. It was just bullshit.”

As the success of Toto IV continued, the band also turned down the cover of Rolling Stone. “We knew it would be a hatchet job,” says Lukather. “You wouldn’t put your cock in front of a chainsaw and go: ‘Okay, pull!”

Toto were so big that they didn’t need the press on their side. But right in that moment, when it seemed as if nothing could go wrong for them, Bobby Kimball was arrested for allegedly selling cocaine to an undercover cop. “Kimball fucked up,” Lukather says bluntly.

Kimball was fired from Toto. It was, according to Steve Porcaro, a decision based not on his arrest but on the effects that cocaine use was having on his voice. “The bottom line was Bobby couldn’t sing. I stayed up all night. We all did. The next day my throat would be like ribbons. But I didn’t have to sing. Bobby had to, and he just wasn’t delivering.”

Lukather doesn’t deny that he and other members of Toto used cocaine in those days – “Hey, it was the eighties!” – but he insists that stories of Toto’s drug use are exaggerated. “If we were really that high, do you think we could have done all those records we did? We were not the only band that did blow. We weren’t as bad as most. But thanks to Mr Kimball, that became like our badge of honour.”

Joseph Williams wasn’t the first singer the band turned to following Kimball’s exit. The follow-up to Toto IV, 1984’s Isolation, featured relatively unknown vocalist Dennis ‘Fergie’ Frederiksen. Isolation was also Mike Porcaro’s recording debut in Toto. But when the album flopped, Williams got the call.

He was someone they had known for years, an LA guy. And there was something else he had in common with Paich and the Porcaros: his father was John Williams, the composer of film scores for Jaws, Star Wars and E.T., and John Williams had worked with Paich’s father and Joe Porcaro. To the guys in Toto he was like family. He passed his audition for Toto by singing like Bobby Kimball. What the band didn’t know at the time was that he also shared Kimball’s taste for drugs.

Williams wasn’t just an over-privileged brat throwing his daddy’s money around. It was more complicated than that. When he was 13 his life was turned upside-down by the sudden death of his mother, the actress and singer Barbara Ruick. In the same year, his father became famous. It was a combination that messed with the young Joseph’s head. “I turned into a bad boy,” he says.

Toto’s first album with Williams was 1986’s Fahrenheit. It also marked the end of Steve Porcaro’s first tenure as an official band member. Despite having made a small fortune out of Human Nature, he felt sidelined in Toto. “I was just programming for David,” he explains. “I didn’t feel wanted.” He continued to work on subsequent Toto albums, and played on two more tours, but he was “relieved” to be out of the group.

Fahrenheit was a good album. It even featured a cameo from jazz-legend trumpeter Miles Davis on the track Don’t Stop Me Now. “We got a lot of love from Miles,” Lukather says proudly. “So fuck all the punk rock critics that went after us.” But the album’s sales were weak. As were those of 1988’s The Seventh One. And soon after, in an echo of what happened to Bobby Kimball, Williams was axed.

“I had a cocaine addiction,” he says. “Nothing abnormal. But as a singer, that’s the one substance you can’t do. It freezes your throat.”

With Williams gone, Toto struggled on. For the band’s eighth album Kingdom Of Desire, Lukather sang all the lead vocals. But before that album was released the unthinkable happened. On the evening of August 5, 1992, Jeff Porcaro died.

Earlier that day, Lukather had spoken to Jeff about the band’s upcoming tour. The conversation ended as it always did, with them telling each other: “I love you, man.” Hours later, he got the call telling him that Jeff had been rushed to hospital after suffering a seizure. In a state of panic, Lukather got lost while driving to the hospital.

“By the time I got there, Jeff was gone,” he recalls. “A doctor took me to a room, and Jeff was lying there on a fucking slab. They left me in that room alone with him, and I freaked out. I was screaming. They had to give me smelling salts.”

The official cause of death was a cardiac arrest due to chemical poisoning: he had been using pesticide in his garden when he experienced an allergic reaction. But there was speculation that Porcaro had overdosed on cocaine. Lukather angrily refutes these allegations.

“It was irresponsible journalism,” he says. “You know, the guy had a wife and kids. He did not die from cocaine. I swear on all four of my children’s lives. They found one one-hundredth of a microgram of cocaine in Jeff’s blood. That’s like two crystals on a fucking matchstick. That ain’t gonna give somebody a heart attack, believe me. The rest of us were doing a hundred times more than that and we all lived to tell the tale.”

Lukather says that Jeff Porcaro had a pre-existing heart condition. He was also a heavy smoker – and this, Lukather believes, is what led to the pesticide getting into Jeff’s system while he was gardening: “He was probably smoking a cigarette or a joint. He didn’t have gloves on. That’s how the chemicals got into his skin.”

What Steve Porcaro remembers most clearly about the aftermath of Jeff’s death was the effect that it had on the entire Porcaro family. “It wasn’t just me losing a brother,” he says. “You see how it affects everyone – his wife, kids, my parents. Before he died we’d been getting along fantastically. At least I had that to hang on to, thank God.”

In their first conversation after Jeff’s death, Paich and Lukather agreed that Toto were finished. “Jeff was our figurehead,” says the guitarist. “We were torn apart.” What saved the band was a discussion in which the Porcaro family told Lukather and Paich: “You should play music. That’s what Jeff would want you to do.” Lukather knew this was the right decision. “What else could we do?” he says. “Sit at home and cry for the rest of our lives?”

With a new drummer, Englishman Simon Phillips, Toto embarked on a tour in support of Kingdom Of Desire. “Somehow we got through it,” Lukather recalls. “Anaesthetising ourselves – not with blow but just drinking.” It was only after the album was released that Lukather saw the symbolism in the artwork chosen by Jeff for the cover: a skeleton clawing to escape its grave. “It was like a premonition,” Lukather says. “As if he knew he wasn’t going to be around.”

The loss of Jeff Porcaro left a profound impression on the band he left behind. “Jeff had an aura,” Lukather says. “When he died, a piece of all of us died with him. I don’t think any of us have ever recovered from that.”

And yet, with Lukather driving them on, the band has continued without its original leader. Between Kingdom Of Desire and Toto XIV there were three albums of original material. Band members came and went. Most surprising of all was the return of Bobby Kimball for 1999’s Mindfields and 2006’s Falling In Between. In all those years, only once was Toto officially disbanded – as declared in a statement by Lukather in 2008. By then he was the sole remaining original member. Paich had retired, Mike Porcaro had quietly left the group due to his declining health. “If there isn’t Paich or at least one Porcaro, how can we even call it Toto?” Lukather said. “This is not a break. It is over.”

What Lukather did not reveal at the time was the personal crisis that had also informed this decision. “I was drinking myself to death, I was losing my marriage, my mother was dying,”he says. “It was a bad time. I needed to get myself together or I was going to end up killing myself. I quit drinking, went to a shrink, exorcised some demons.”

It was the announcement of Mike Porcaro’s illness in 2010 that brought about the reunion of Toto and a world tour to raise awareness of ALS. The tour marked the return of Steve Porcaro and Joseph Williams, alongside Lukather, Paich, Williams and bassist Nathan East. The exclusion of Bobby Kimball led to a feud between him and Lukather. This is one subject on which Lukather will not be drawn. “I don’t want any enemies in this world,” he says. “Life is too short, man.

This band knows it more than most. Lukather reveals that Steve Porcaro has also experienced serious problems with his health. “Steve had a tumor removed in his brain. It was benign, thank God.”

During the years they spent away from the band, both Steve Porcaro and Joseph Williams developed careers making music for film and TV. Even though Steve made a lot of money out of Human Nature, he is twice divorced, with three children. “I have to keep working,” he says. What this album represents to Joseph Williams is an opportunity to put right his past mistakes. “It is a second chance for me,” he says.

David Paich has no idea if Toto XIV is their last album. “I thought we’d made the last one ten years ago,” he says, “so it’s amazing that we’ve pulled this thing off. I guess that after all that’s happened to this band we’ve learned to live a day at a time.”

When Steve Lukather thinks about the longevity of Toto, he starts to laugh. Mostly he’s laughing in the faces of those who wrote off his band so many times in the past. “We’re still here,” he says. “They tried to stop this band but they couldn’t. In the end, we won.” The laughter ends when his thoughts turn again, as they always do, to Jeff and Mike Porcaro. There is no separation between the story of Toto and the story of the Porcaro family.

“Sometimes I feel like the luckiest man in the world,” Lukather says. “This band has been so good for me for so long. But what this band has been through, what that family has been through, it changes you. When you’ve seen the things that I’ve seen, you know how fragile life is.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”