The band with the thousand pound album

The Courtyard Music Group formed at school and made one ridiculously rare album. Now they're releasing a replica, and playing their first show in 40 years.

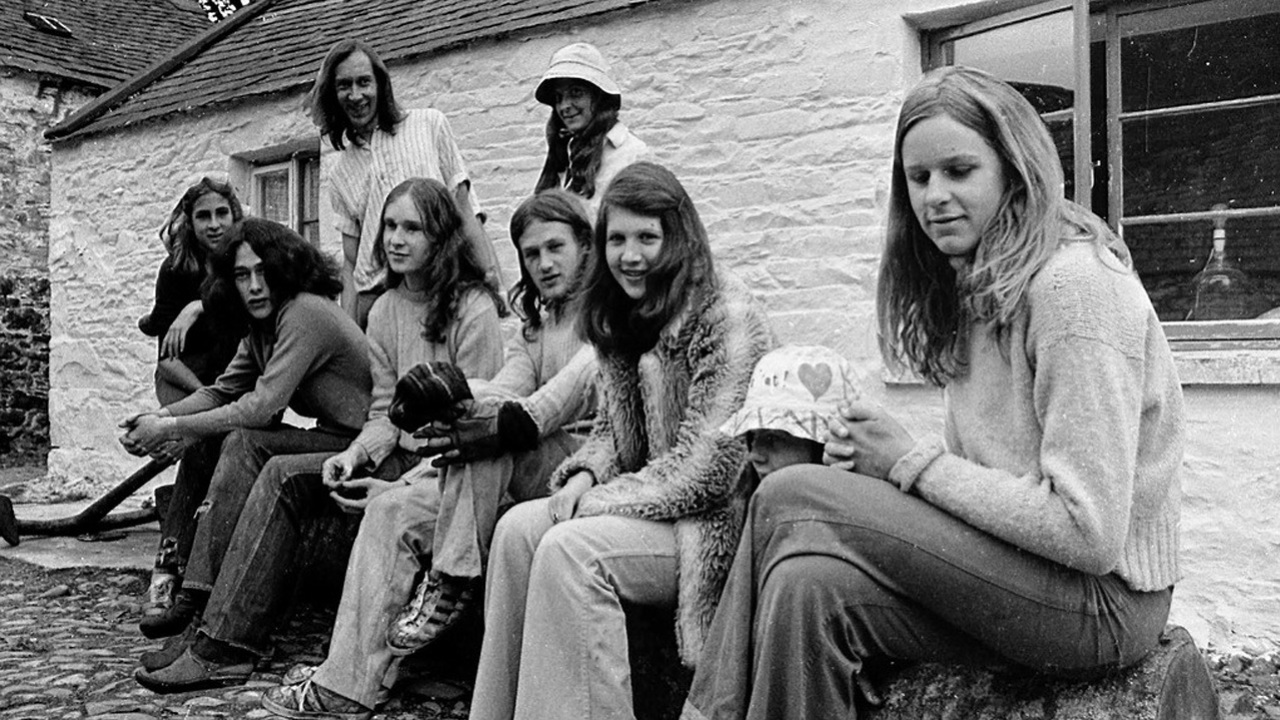

Once upon a moonbeam, when hair was long, trousers were purple and albums came in gatefold sleeves with madly grinning wizards on the front, an idealistic young teacher cut a lo-fi folk-rock record with a bunch of teenagers in the Utopian rural setting of Kilquhanity School in the Scottish borders. Recorded in 1974 under the collective name Courtyard Music Group, Just Our Way Of Saying Hello was then privately pressed in a run of 100 copies for band, family and friends. And they all lived happily ever after. The end.

Well, not quite. Fast forward a few decades, and one of the most obscure albums in Britfolk history is now an ultra-rare collector’s item, with copies trading online for over £1000. And now the team behind the original recording have regrouped for the first time in 40 years, launching an online pledge campaign to fund a new limited-edition pressing of the album on deluxe vinyl, plus a one-off reunion show in August to mark the school’s 75th anniversary.

Steeped in Celtic folk and pastoral blues, Wicker Man ambience and Floydian mysticism, Just Our Way of Saying Hello has a charming, unforced freshness to it. Richard Jones, the former Kilquhanity woodwork teacher who ran the Courtyard Music Group, believes the album captured a rare natural alchemy between its untrained players, which helps explain why it stands up today.

“There are still moments in it now that I think stand up superbly,” Jones says. “Just little moments where a group is being much more than the sum of its parts and the whole thing - instrumental technique, arrangement and performance - is playing itself. That was always my aim in music, that’s what the song The Magician was about, because occasionally we did hit those moments.”

“I hadn’t listened to it for years, and it really took me right back to the whole school thing,” says Annie Vickerstaff, who played recorder on the original album. “I was amazed to learn it had become a collector’s item. It’s very much of that Pink Floyd era, in fact I think there were a couple of kids at the school who had connections with Pink Floyd, their parents knew the band or something. Not that they were ever involved in our music group, but there was just that kind of vibe hanging around.”

The key to the album’s existence was the unorthodox educational ethos at “Killy”, as the former band members affectionately call their alma mater. Modelled on the celebrated English school Summerhill by founder and headmaster John Aitkenhead, Kilquhanity was a “free school”, a term with right-wing political associations today, but which once denoted a kind of Utopian democratic experiment where students and teachers had equal votes in council meetings, lessons were fluid and children encouraged to fully explore their creative side.

“Kilquhanity was an amazing place and an experience every kid should have,” recalls Howard Bradley, bassist and percussionist on the album. “A school where self expression and creativity went hand in hand with learning to live in a community and play your part therein.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

To outsiders, of course, Kilquhanity does sound ever so slightly like a long-haired, dope-smoking, free-love experiment. Indeed, some of the gear for the album was borrowed from a nearby hippie commune, Laurieston Hall. “Almost all of us had long hair, but I wouldn’t say we were ever hippies or that the school was any kind of hippie commune,” recalls multi-instrumentalist Frank Swales. “Sure, some of us smoked, and some of us might have experimented with certain ‘herbal cigarettes’ and alcohol, but wasn’t that happening as part of the overall Western culture at that time anyway?”

“It was unusual and very creative,” explains Mary Cartwright Lestrange, vocalist and percussionist. “Yes, boys could grow long hair and there was a certain amount of freedom regarding academia, but there was a structure to the school which kept things in place and it felt like one big family.”

Now mostly in their fifties, the former CMG members are scattered around Britain today. After school, all pursued careers outside music, although Swales later played in several bands, and Jones is involved with two 16th century music groups. He also manufactures viols, vintage instruments with a three-year waiting list.

Stephen Bateman, who served as a 12-year-old technical assistant on the album, is the driving forces behind the re-issue. On top of his day job in publishing, Bateman is supervising the painstakingly forensic new vinyl pressing from high-end lacquer discs, analogue to analogue. “There will be no digital interference in the process,” he stresses.

Of course this whole antique, artisan, bespoke process is a key element of the project’s alluringly retro aura. CMG are not just selling charmingly innocent music but nostalgia for simpler times, when albums were physical artefacts, music had magical powers and childhood summers lasted forever.

“I understand where that comes from,” Bateman nods. “The young generation these days with their playlists don’t have any tangible trace of what they’re listening to, and no affection for the artists because they don’t have the record covers. There is something to that.”

Frank Swales agrees. “There is an element of nostalgia, of course,” he says. “If our album has anything real to say it might be along these lines: from time to time, just pull yourself away from your iPods and iPhones and computers, get together with a couple of musician pals and just have a jam!”

Just Our Way Of Saying Hello can be pre-ordered from Pledgemusic.

Stephen Dalton has been writing about all things rock for more than 30 years, starting in the late Eighties at the New Musical Express (RIP) when it was still an annoyingly pompous analogue weekly paper printed on dead trees and sold in actual physical shops. For the last decade or so he has been a regular contributor to Classic Rock magazine. He has also written about music and film for Uncut, Vox, Prog, The Quietus, Electronic Sound, Rolling Stone, The Times, The London Evening Standard, Wallpaper, The Film Verdict, Sight and Sound, The Hollywood Reporter and others, including some even more disreputable publications.