The 100 Greatest Blues Singers

We asked you to vote for your favourite vocalists, and you made yourselves heard.

19) Albert King: He made fat stacks for Stax…

Albert King had already enjoyed a hit with Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong before his 6ft 4in, 18st frame cast a shadow over the threshold of Stax Records in 1966. The man nicknamed “The Velvet Bulldozer” was ready for more. Backed by Stax house band Booker T & The MGs he cut his landmark album Born Under A Bad Sign. A showcase for his booming vocal style, the album made him an icon. “If it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have no luck at all,” said Booker T, quoting from the title track. “That’s the blues! And we defined it a little bit that day.” EM

18) Aretha Franklin: She paved the way for every female singer since.

Aretha never strayed far from church, her vocal enriched by her gospel background. She rarely belted it out, but when she did, as on Rough Lover, she was a match for Etta James. Most of the time, though, her approach was more considered, a fine balance of emotion and restraint.

Versions of Otis Redding’s Respect, BB King’s The Thrill Is Gone and Don Covay’s Chain Of Fools she truly made her own; originals such as Think and I Never Loved A Man are the very essence of soul. AC

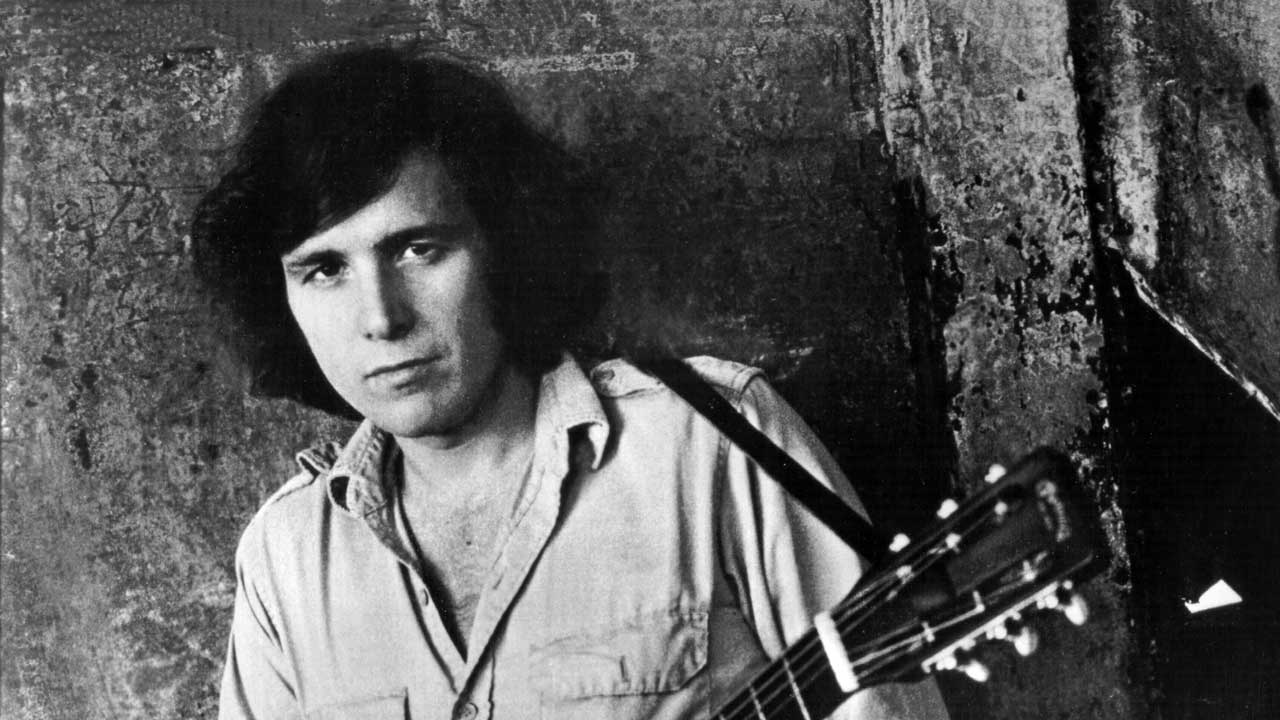

17) Steve Marriott: From ace face mod to rock royalty.

While he cut some incredible vocals with the Small Faces – All Or Nothing, Afterglow (Of Your Love) and the peerless Tin Soldier – by the end of the 60s, Steve Marriott began to distance himself from his cheeky pop star persona. His desire to be taken seriously and move in a heavier direction led to the formation of his blues rock’n’soul outfit Humble Pie.

Ironically, his thunder was robbed by the rise of Led Zeppelin, yet it was Marriott who inspired the vocal histrionics of Zep’s Robert Plant. Compare Marriott’s vocal on the Small Faces’ You Need Loving – their take on the old Willie Dixon tune You Need Love – with Plant’s performance on Zeppelin’s reboot Whole Lotta Love. It’s too close to be a coincidence.

Marriott’s greatest post-Small Faces vocal occurs on the old Ike And Tina Turner cut Black Coffee, on Humble Pie’s ’73 album Eat It. The studio version is great but you should eyeball his performance on the BBC TV show The Old Grey Whistle Test on YouTube. Marriott’s Artful Dodger side is on display in a TV moment that proves he was one of the greatest white singers Britain ever produced. EM

16) Junior Wells: Wailing harp and funky vocals made the hoodoo man’s blues.

Like Little Walter, Wells’ first instrument was blues harp, and when the former left Muddy Waters’ band, Wells took his place. When he sang he made a joyful noise; inspired by James Brown, the Hoodoo Man Blues album with Buddy Guy is a classic. JH

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

15) Koko Taylor: Powerhouse vocalist dubbed queen of the blues; responsible for Wang Dang Doodle.

Chicago’s Koko Taylor had a fierce roar that placed her in the grand tradition of blues shouters. What made her exceptional was the power behind her delivery and her emotionally nuanced phrasing. A cross-generational influence, Bonnie Raitt, Shemekia Copeland, Janis Joplin and Susan Tedeschi all owe a debt. AC

14) Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland: The expressive voice that mixed gospel, country and electric blues and gave rise to soul.

Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland honed his craft alongside BB King, Junior Parker, Johnny Ace and Rosco Gordon on Memphis’ Beale Street, but it was on signing to Duke that he came of age with a voice that earned him the nickname Lion Of The Blues, for he could in the space of a song go from a deep, strong, guttural roar, to a velvety soft purr. It was a winning combination, with Bland notching up 25 US R&B Top 10 hits between 1957 and ’74. Van Morrison and James Hunter are both indebted. AC

13) Bessie Smith: The empress of the blues.

Chosen by Dana Gillespie: “When I was 11, my sister threw out an EP, which I rescued, and it had a track on it by Bessie Smith. I loved her voice from the moment I heard it. I sang along to Empty Bed Blues, not understanding the lyrics but engaging with the emotion.

“You never get let down when you hear her. I started to read about her life, her disastrous love affairs, how awful she must have felt. Her singing heals the soul. She was doing gig after gig. How did she cope with having no microphone? Her voice must have been tough as old boots.”

12) Tom Waits: The poet laureate of the gutter.

There are plenty who would question Waits’ inclusion in this list. His voice is, after all, an acquired taste, from the smoker’s rasp he’d perfected as a young man to the unique, gnarled bark we hear today. But, with shades of Howlin’ Wolf, it exudes perfect theatre, his early bar-floor view of the world’s deadbeats and lost souls infused with a sense of romance that’s pure Americana, a world of diners and classic cars, Edward Hopper’s paintings and Jack Kerouac’s pie-eyed ramblings.

And in recent years he’s become ever more inventive. While the sinister Bone Machine found him roaring the darkest, most primal of blues, by the experimental Real Gone he was distilling his coughs, growls and splutters into percussion, while What’s He Building? from Mule Variations is a masterclass in avant-garde spoken word drama. EJ

11) Janis Joplin: A dramatic voice in a blues rock setting.

In Janis Joplin’s too brief life – she died aged 27 on October 4, 1970 from a heroin overdose – she achieved so much. Big Brother And The Holding Company 1967’s self-titled album and 1968’s Cheap Thrills are both exceptional albums, the latter going gold. Her two solo records, 1969’s I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama! and 1971’s Pearl are ace, too, and all are motored by a voice defined by interior damage.

An outsider, raised in Port Arthur (a very conservative town in Texas) who needed social acceptance but refused to conform, Janis was relentlessly bullied for her unconventional looks and liberal politics and the scars never healed. Music provided sanctuary though. Aretha Franklin and Etta James were important to her development. Otis Redding too, whom she called “my man” after watching him perform at the Fillmore while on LSD. Her own onstage and in-studio personality, though, was all her own.

With fire in her belly and an explosive rasp, she hollered through songs full throttle. Incendiary takes on Ball N’ Chain – her performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 is truly amazing – and Piece Of My Heart are the eureka moments. AC

10) Freddie King: The man who was instrumental in Clapton’s blues education…

One of The Texas Cannonballs’ most influential albums was 1961’s Let’s Hide Away And Dance Away With Freddy King (he changed the spelling of his Christian name to Freddie later). Album track Hide Away was covered – as Hideaway – on the 1966 John Mayall Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton ‘Beano’ album; The Stumble was cut with Eric’s replacement Peter Green on ’67’s A Hard Road. Ironically, though, the original Freddie King album was all-instrumental – he was an exceptional guitarist – yet the big man was an outstanding singer.

Like BB King, and others who used a similar approach like Buddy Guy and Magic Sam, Freddie could bellow out a melody before suddenly swooping to a sweet falsetto. The ultimate example of the man’s power is his performance on the 1960 single Have You Ever Loved A Woman, a standout track on his 1961 album Freddy King Sings, and, as the title suggests, it was not instrumental.

The song is a favourite of King disciple Clapton who performed it live with the Bluesbreakers in 1965 before cutting it with Derek And The Dominos on the 1970 album Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs. King was also an important influence on fellow Texan Stevie Ray Vaughan. EM

9) Paul Rodgers: The Free frontman belts ’em out.

As Free and Bad Company’s frontman, Paul Rodgers templated the sound of the archetypal hard rock singer. At the core of Rodgers’ voice is the raw emotion of his favourite vocalists: Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin. “I never had any formal training,” says Rodgers now. “It comes naturally but I still have to work at it and I still do, it’s my passion.”

But on career highlights such as Bad Company’s Feel Like Making Love and Free’s All Right Now, Rodgers counterpointed that soulful quality with swagger and machismo. Rodgers always sings like he’s about to have either the best sex or the best fight of his life – or possibly both. It’s this distinct quality that acolytes including Whitesnake’s David Coverdale and Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Ronnie Van Zant copied, but could never quite match.

Some of Rodgers’ best vocal performances have also been his gentlest: try the Bad Company album track Silver Blue And Gold or Free’s Come Together In The Morning. Rodgers himself suggests That’s How Strong My Love Is and I’ve Been Loving You Too Long, from 2014’s The Royal Sessions solo album as some of his best work. “It’s nice to be voted into the Top 10 Greatest Singers,” he says. “But for people to feel what I feel through music is its own reward.” MB

8) John Lee Hooker: How the boogie man made his mark.

Chosen by Jim Jones: “John Lee Hooker has a depth of tone to his voice that when you hear it, it feels like it was already inside you, so when you’re listening to it, it feels like you are remembering something rather than hearing it for the first time. His voice makes me think of the Mississippi River, the way it moves and twists and it has a gentleness, but it can be mean and powerful, and you can hear the parts of the land the river winds through in it.

“There are his talking songs like Tupelo Blues and I’m Bad Like Jesse James, and his half-talking, half-singing songs like Henry’s Swing Club, Boogie Chillen and Leave My Wife Alone and when he talks, his voice is so powerful it leaves an imprint on you. It holds you until he says the next line. Like in Tupelo Blues, it is mostly silent, but then he says a line and it grips you until he says the next line. It resonates.

Then there are the songs where he just sings: Down Child has it all. It is beauty and the beast, his voice sounds so earthy and it makes me think of the tortured cries of a dangerous animal in a bear trap or a powerful animal that’s been caged, and it rips straight through you. Onions, his take on Green Onions, pairs him with a horn section and his voice is more shouting than singing, but his phrasing is great, and his delivery, it’s driving and so sharp, it’s like the lashing out of a tiger’s claws. But it has weight behind it too, so when it catches you, it can take you down in one swipe.

Then there are his ballads like Take Me As I Am. It’s like a beautiful lullaby, very tender, and there is an incredible honesty in his voice and it goes straight into your soul. It captures the raw human spirit and our vulnerability.”

7) Billie Holiday: Lady Day, the woman who created genius from tragedy.

Abused as a child and a heroin addict in later years, Billie Holiday carried a lifetime of tragedy in her voice; with every breath and quaver, a heart-stirring story unfolds. Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith were pivotal influences on the singer who producer John Hammond called “an improvising jazz genius” and soon the teen was working with Teddy Wilson, Lester Young and Artie Shaw. 1938’s You Go To My Head captures her early period best: Holiday, given over to the thrill of abandonment, uses her voice to convey the spectrum of emotion from joy to pain.

It was the following year, though, that she delivered her greatest vocal performance on a song that arguably began the civil rights movement. Billie first sang Strange Fruit, which originated from the poem written by Abel Meeropol under the pseudonym Lewis Allan, at the Café Society in Greenwich Village; her mournful, poignant delivery was so powerful it left the audience in tears. Columbia refused to issue the protest song but released her from her contract so she could record it for her friend Milt Gabler’s Commodore label. It went on to sell over a million copies and still sends shivers down the spine today. AC

6) Howlin’ Wolf: The mighty Wolf rocked Chicago with a howl from the soul.

Chester Burnet, aka Howlin’ Wolf, was an imposing figure at 6ft 3in and almost 20st, with a uniquely powerful voice that alternates between a gravelly growl and an almost supernatural howl on signature songs such as Smokestack Lightning and I Asked For Water, both from 1956.

Initially recording in Memphis with producer Sam Phillips at Sun Studios, the results were licensed toChess in Chicago. The first 25 seconds of Wolf’s 1951 debut, recorded by Phillips, Moanin’ At Midnight are truly extraordinary, featuring eerie, wordless moans that seem to emanate from somewhere deep within Wolf’s mighty frame. When combined with the low guttural grit of Wolf’s voice on flip side boogie How Many More Years, it is easy to see why Phillips declared: “When I heard him, I said: ‘This is for me. This is where the soul of man never dies.’”

At Leonard Chess’ instigation Wolf relocated to Chicago in 1953 and, backed by guitarist Hubert Sumlin, recorded blues classics such as Evil (1954) and Spoonful (1960). When The Rolling Stones went on the American TV show Shindig! in 1965 they insisted that Howlin’ Wolf appear too. The Yardbirds turned Smokestack Lightning into a rave-up while Captain Beefheart and Tom Waits are obvious devotees. JH

5) Robert Johnson: Forget the devil, this guy had the best tunes.

No blues artist has had their genius obscured beneath a layer of bullshit, misinformation and good old fashioned hokum like Robert Johnson. The myth is he travelled to the crossroads in Clarksdale, Mississippi, to flog his eternal soul to the devil. In return, it was said, Johnson would receive killer guitar chops that would leave his rivals quaking in their boots. It’s a fun tale that was falsely attributed to Robert. It was actually Tommy Johnson, the troubled soul who penned Canned Heat Blues who spun the satanic yarn, about himself, as a sly piece of marketing.

The truth is that Robert Johnson was gifted. Keith Richards was convinced there were two guitarists playing on Johnson’s records when he first became acquainted with the bluesman’s work in the early 60s. There weren’t. And there’s Johnson’s haunting falsetto vocal style on tracks like Sweet Home Chicago, Come On In My Kitchen and Cross Road Blues. He might have left this world “barking like a dog” after being poisoned by a jealous husband, but on record, Johnson sang like an angel and influenced everyone from The Rolling Stones to Cream and Led Zeppelin. As Eric Clapton once said, Robert Johnson was the “most important blues singer that ever lived.” EM

4) Muddy Waters: The hoochie coochie man with the virile baritone who fathered Chicago electric blues.

The father of modern Chicago blues, McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters, was an expert slide guitarist who transposed country Delta blues to urban electric, but his rich baritone voice was his greatest asset and instantly recognisable. In fact, some of his best known songs recorded for Chess Records in Chicago such as I’m Ready (1954) and Mannish Boy (1955) feature only vocals from Waters backed by his template-setting electric blues band, that included Little Walter on harmonica, guitarist Jimmy Rogers and bassist Willie Dixon.

The virility of Waters’ performances meant he was never overshadowed, though. Waters’ voice had an emotional depth and versatility reflected at its purest in his first single for the Chess brothers in 1948, I Can’t Be Satisfied and its B-side I Feel Like Going Home, which feature only Muddy’s slide and Ernest “Big” Crawford’s bass behind Waters’ voice. And what a voice: by turns yearning, threatening and, particularly on the latter, playful and excited, crying out ‘yeah!’ in satisfaction as he pulls off impressive slide.

When Johnny Winter produced Waters’ superb comeback album Hard Again in 1977, Winter played many of the guitar licks but Waters’ magnificent voice boomed out strong and proud again. Arguably, all electric blues and rock owes something to Muddy, but The Rolling Stones (named after his song Rollin’ Stone) are among the most obviously influenced. JH

3) Robert Plant: The golden god with the 24-carat shriek.

If there’s a more thrilling opening gambit than the first 10 seconds of Led Zeppelin’s fourth album, we’ve not heard it. There’s a strange juddering sound. A tantalising split-second of silence. Then comes Black Dog’s scorched-earth a capella vocal: ‘Hey hey mama, said the way you move, gonna make you sweat, gonna make you groove…’

By that juncture in 1971, Robert Plant was the most celebrated singer on the planet. Strange to think that he wasn’t even Jimmy Page’s first choice to front Led Zeppelin. After an attempt to poach Steve Marriott resulted in the guitarist being threatened with broken fingers by Small Faces manager Don Arden, Page saw Plant sing for the first time at a Midlands teacher-training college on July 20, 1968, and realised he was looking at the missing piece.

“His vocal range was unbelievable,” remembers the guitarist. “I thought, ‘Wait a minute, there’s something wrong here. He’s not known…’”

He soon would be. Page might be remembered as Zep’s de facto leader, and his power-blues riffing as the engine-room, but it was Plant’s untamed delivery that brought the sex and drama; his top-lines that you screamed back as the band grew from student unions to Madison Square Garden. When Plant sang, he used his entire body, becoming a whirling dervish of sound and vision. “When you’re up there enjoying yourself,” he told Melody Maker in 1970, “the physical side has to come in too.”

Zeppelin’s 12-year tenure is sprinkled with Plant’s unmistakable genius. The explosive arrival of Good Times Bad Times. The rampant retooling of the blues masters on I Can’t Quit You Baby and In My Time Of Dying. Those mid-coital moans in the breakdown of Whole Lotta Love. And the call-and-response ‘aw-haw’s peppering the aforementioned Black Dog.

The shriek takes top billing, but when Percy wasn’t whooping it up, he could sound naked and heartfelt, as on Thank You and Going To California. And while everyone talks about Page’s guitar masterclass on Since I’ve Been Loving You, Plant is absolutely his equal in every way on that seven-minute epic, expressing a mournfulness on the ‘working from seven’ sections that betray the early influence of Robert Johnson (“When I first heard Preachin’ Blues and Last Fair Deal Gone Down, I thought, ‘This is it!’”)

Plant has lost a bit of range since Zep’s 1980 split, but none of his ambition as a vocalist, testing himself in projects from the Americana of Raising Sand (alongside Alison Krauss) to the African inflections of Lullaby And… The Ceaseless Roar (“For me, as a singer,” he told The Quietus, “you can play some beautiful melodies over drones.”).

Page, for his part, has spent his entire career trying to replace that voice, working with belters including Paul Rodgers, David Coverdale and Myles Kennedy (after Plant declined a full Zeppelin reunion tour in the post-millennium). Respect to those singers, but it was never the same. Robert Plant is a titan, a golden god, a once-a-generation phenomenon. He’ll make you sweat. He’ll make you groove. HY

2) Etta James: The female blues singer.

“I learned to ‘sing like your life depends upon it,’” Etta James said. And she sure did, for Etta could beg, scream and shout, and was dubbed the first queen of soul some 10 years before Aretha Franklin. She mixed the church with the street, first at Modern, where she recorded undistilled, filthy rock’n’roll and birth-of-soul ballads from 1954 to ’59, and then at Chess where between 1960 and ’76 she delivered mighty sock-it-to-them rockers and heartbreak soul.

Her story begins at the St Paul Baptist Church in Los Angeles where, under Professor James Earle Hines, a five-year-old Etta sang Didn’t It Rain and Move Up A Little Higher. Soon, though, there was tragedy as she was abandoned by her prostitute mother. It all took its toll; there were drastic personal consequences – alcohol and drug addiction, nervous breakdowns, eating disorders; at her heaviest she weighed almost 30st. A gastric bypass in 2001 reduced her to half that size, but she dug deep and singing acted as catharsis.

Her debut 45, 1955’s The Wallflower (aka Roll With Me Henry) was produced by Johnny Otis and introduced a sassy singer from the wrong side of the tracks, who meant business; its risqué subject matter caused a stir; it also landed her a US R&B No.1. 1956’s Tough Lover, meanwhile, captured her whirlwind, frenzied hollering and wailing.

It was at Chess, though, that she set the benchmark for blues and soul vocalists with 1961’s At Last, her label debut arranged by Riley Hampton. The title track, which placed her in a dramatic orchestral setting, became her signature. 1964’s Rock The House proved she could do it all live too. The album, recorded over two nights at Nashville’s New Era Club in 1963, is pure on-your-feet excitement from start to finish.

1968’s Tell Mama is her masterpiece, where everything falls naturally in to place. Teamed with Rick Hall at Fame Studio with Hall’s in-house band, her performance is spectacular throughout. The incendiary title track, a cover of Clarence Carter’s Tell Daddy, provided her with her highest pop place in America to this day when it reached No.23. The song’s B-side, I’d Rather Go Blind co-written by Etta, is an anguished, deep soul ballad, and contains one of Etta’s most heartfelt vocals and its influence is omnipresent.

Chicken Shack took their reading into the Top 20 in 1969, Rod Stewart did it in ’72, Janis Joplin, who modelled her whole career on Etta’s, regularly performed it live. Etta, in turn, looked to Janis for inspiration in the 70s, teaming up with her one-time producer Gabriel Mekler on 1974’s rockier Come A Little Closer and 1976’s Etta Is Betta Than Evvah!, which experimented with funk rock. Etta was still singing her heart out right up until her death. Her swansong, The Dreamer – recorded while she was suffering from leukaemia and released just two months before her death on January 20, 2012 – hit the US Blues No.2 spot. AC

1) BB King: There’s a reason he’s the king of the blues.

Who else? With due respect to the towering voices of the blues – the rasp of Wolf, the drawl of Muddy, the croak of Hooker – no one has ever opened their mouth to such earth-shattering effect as Riley B King. To hear the man sing was to be lifted above the slurry of life, to feel your bones warmed and your soul soothed. To speak afterwards was to be suddenly conscious of sounding like a white suburban pipsqueak.

A musicologist might focus on the extraordinary vocal range, a biologist on the unprecedented lung power, a comedian on the impeccable timing. But perhaps the critical point is that BB King’s voice was, above all, real; a sound born of the earth; a happy byproduct of a hideous culture never to return.

“The holler is where it all started,” he once noted, referring to the lone voice of a picker that rang out as the mule hoed the cotton fields of 30s Mississippi. “I think it’s in all of us.” The young King refined his own voice in church, and monetised it on the Delta’s street corners. “People would walk up to me and ask me to play a gospel song,” he remembered in The Telegraph, “and they’d pat me on the head and say, ‘That’s nice, son’. But they didn’t tip at all. But people who ask me to play the blues would always tip me. I’d make $40, $50. Even as off in the head as I am, I could see it made better sense to be a blues singer.”

It’s ridiculous to think how young King was when he poured soul into 50s sides like Three O’Clock Blues, and patently obvious from revisiting such cuts that his voice would soon take him places. The lucky few among our readership might remember how it felt to witness King in his 60s pomp, crushed in among the bodies, basking in his glow.

For the rest of us, there’s 1965’s deathless Live At The Regal: an album that bottles all the factors that make the bandleader top of the pile. “It’s a record that Eric Clapton and I discovered at the same time,” noted John Mayall. “It’s a special record.” From the boom of Every Day I Have The Blues, through the tender rave-up of Sweet Little Angel, to the soaraway falsetto of It’s My Own Fault, this is King in excelsis, his alternating use of vocal and guitar allowing total expression.

“He was a one-off,” says Robert Cray. “He had pure power, when he wanted it. And he was a crooner, too – he played a lot of ballads, as well as pounding the blues into you. He could draw you into himself, then deliver the story to you. I think that’s the most important thing.”

For evidence of that storytelling flair, try the crowd-revving comic genius of Regal’s How Blue Can You Get? (‘I bought you a 10 dollar dinner, you said thanks for the snack. I let you live in my penthouse, you said it was just a shack. I gave you seven children… and now you wanna give ’em back!’). For his part, King saw it all as part of the gig: “I don’t try to just be a blues singer – I try to be an entertainer. That has kept me going.”

Unlike many of his contemporaries, King’s voice would only grow in stature and gravitas with age. In 1970, neck-tingling confessionals such as Chains And Things lit up Indianola Mississippi Seeds (King himself preferred the album to Regal), and in 1988, his guest-spot on U2’s When Love Comes To Town put Bono’s counterpart vocal in the shade. “I gave it my absolute everything I had in that howl at the start of the song,” noted the Irishman. “Then BB King opened up his mouth and I felt like a girl.”

However, even his most ardent admirers had to admit that King, inevitably, went downhill in his final years. Yet while his touch on Lucille grew ever more haphazard, that voice was the last thing to desert him. “I went to see BB King on my birthday two years ago,” recalls Phil Collen of Def Leppard and Delta Deep. “I met him and I told him – and he sang me Happy Birthday. I was like, ‘Wow, this is fucking cool’. It was a bit surreal. It was like, ‘Fuck me, BB King is actually singing me Happy Birthday.’ His health was fading by then, he was actually in a wheelchair. But he still sounded so good.”

There are many others who can hit the notes. But when BB King sang, it went deeper, connecting with the listener on a base level, jump-starting our humanity, making us all better people just by association. Our number one blues singer of all time, then. Like we say – who else? HY

Current page: The 100 Greatest Blues Singers (19-1)

Prev Page The 100 Greatest Blues Singers (39-20)