Riots, revolution, and the righteous path of The MC5

Lenny Kaye's book Lightning Striking tells the story of 10 transformative moments in rock'n'roll history, from Seattle to Detroit and beyond

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

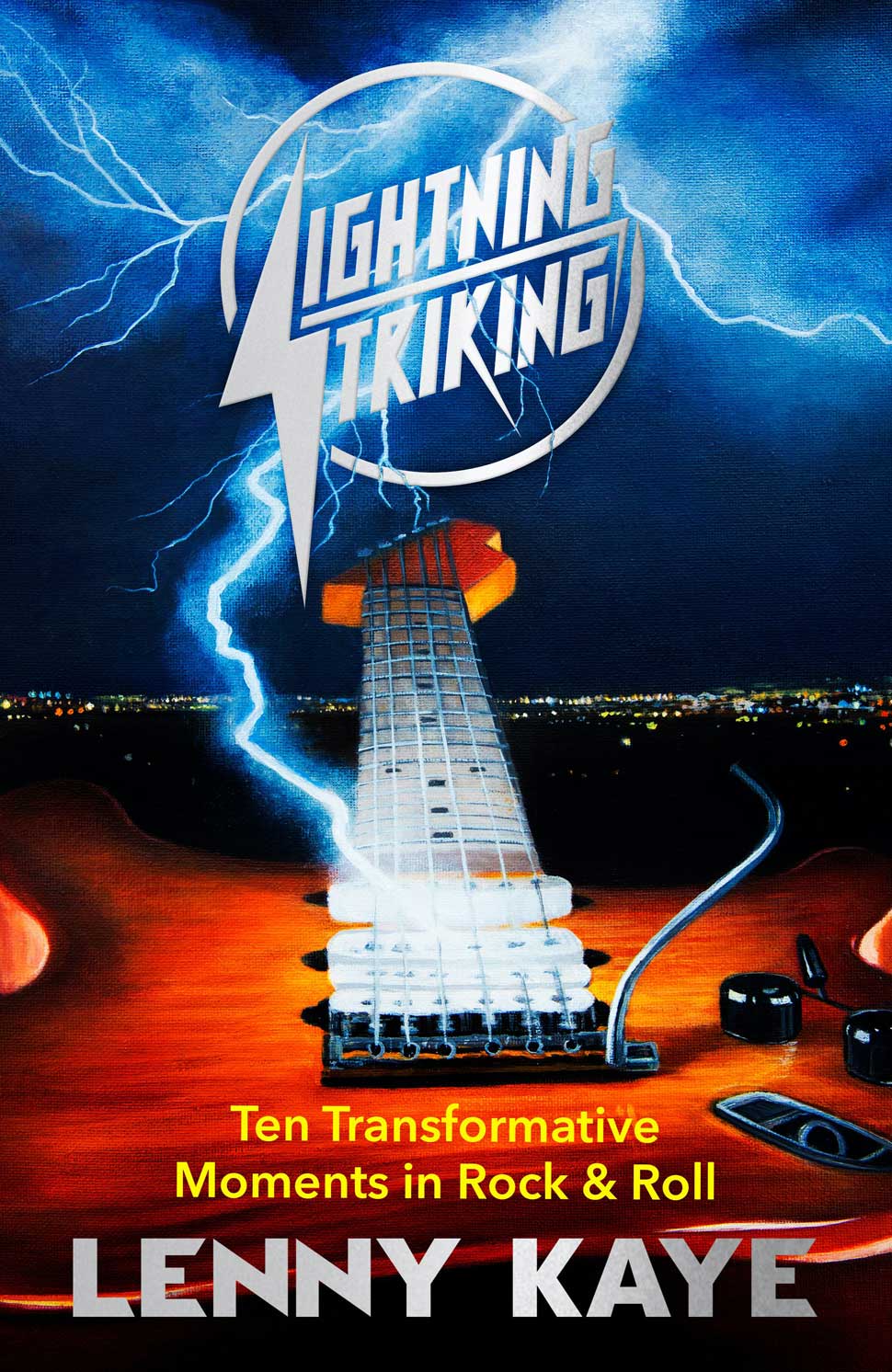

Lenny Kaye's book Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments In Rock & Roll tells the story of 10 flashpoints in musical history. It visits Memphis when Elvis Presley was getting started. It explores the Liverpool of The Beatles. It takes in San Francisco in 1967, Los Angeles in 1984, and Seattle in 1991. It's a guided tour of revolution.

In the excerpt bellow, Kaye takes a trip to The MC5's Detroit. It's 1967, and the Motor City is burning.

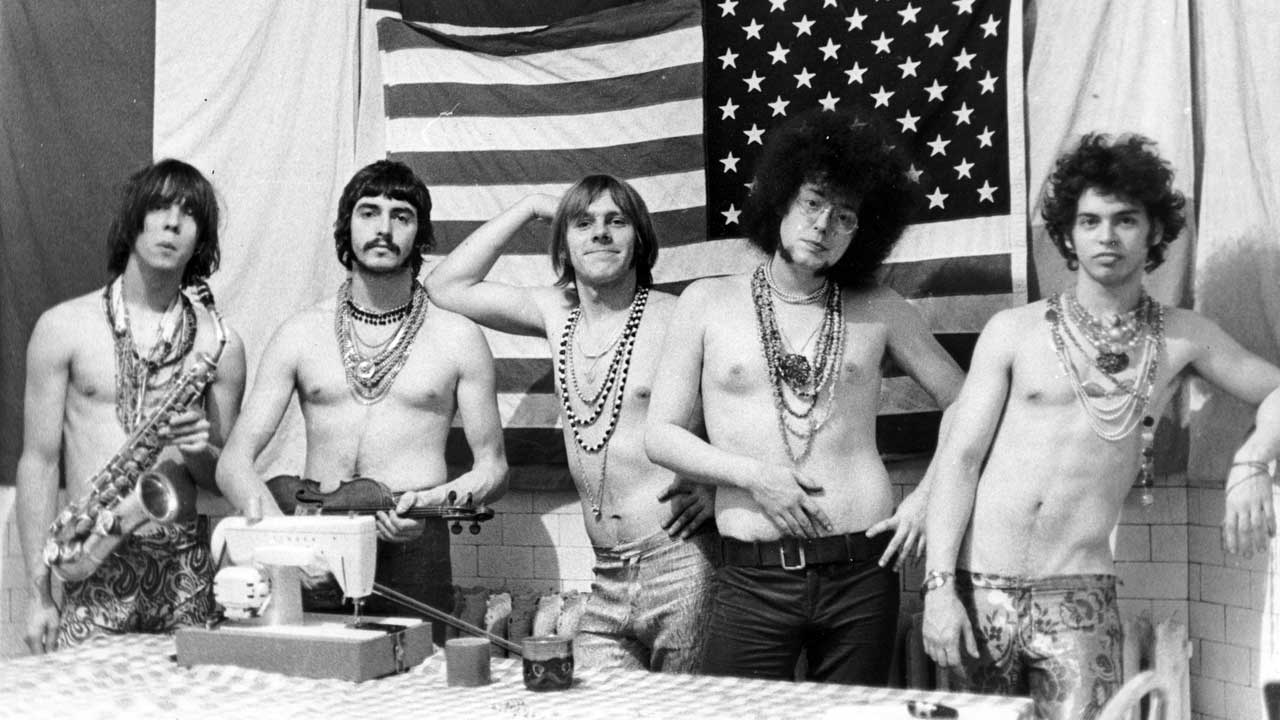

The MC5 moved into the Trans-Love commune in time to suffer the backlash of the riots. Their equipment van was firebombed; they were subjected to random police provocation and accused of disturbing the peace, which was the stated intent. There was no distance between being a target and their no-quarter-notes-given stage show.

They were used to Battles of the Bands, and they challenged touring superstars who made Detroit a stopover at the Grande, daring anyone – Cream, Blue Cheer, The Yardbirds in the months before they became Led Zeppelin – to top their raw volatility. Trans-Love preacher “Brother” J. C. Crawford worked the body heat of the hometown crowd, urging to see a sea of hands, rise up, take control, a true testimonial as he emcee’d The MC5.

They launched from the stage like a landing party hitting a beach, a rush of battle joined. Wayne Kramer falsetto’d Ted Taylor’s Rambling Rose, Rob Tyner shouted the call to arms of Kick out the jams, motherfucker!, and then they pressurised John Lee Hooker’s Motor City Is Burning, Sun Ra’s Starship #9, and their own Rocket Reducer No. 62, putting the Rama Lama in the Fa Fa Fa.

Spangled, strobed, stun-gunned. It was getting too dangerous in Detroit, even as the MC5’s residency at the Grande created a homing signal for the estranged. In the spring of 1968 Sinclair moved Trans-Love to 1510 Hill Street in Ann Arbor. The university town had a reputation for political resistance – as did most colleges then, especially with the military draft only a letter grade away – and over the course of the summer, like the contrarian culture surrounding them, Trans-Love turned militant, armed and combat ready, at least in photographs where the MC5 brandish guns for guitars, one weapon and the same.

If it was a pose, stationed at the barricades of manager John Sinclair’s “total assault on the culture,” it was reactive to a world where student demonstrations fought Paris to a standstill, assassinations – from King to Robert Kennedy and even an attempt on Andy Warhol – split the screen, and “police versus young people” waged their courtroom drama outside the legal system.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Suffering an all-too-real body count, the Black Panthers were wilfully dismissive of the White Panthers, as the political arm of Trans-Love called itself in solidarity, dismissing them as “psychedelic clowns.” There was some truth to this, Trans-Love playing court jester in the face of oppression.

“We were the furthest thing from a political organisation that you could possibly imagine,” Sinclair admits today, but he doesn’t recant his belief in the White Panthers’ ten-point program: freedom the power of all people to determine their own destinies free planet free food free media freedom of all political prisoners free world economy free access to all information free educational system free free free.

The MC5 took this free-for-all to Chicago’s Lincoln Park on August 25, 1968, for a “Festival of Love,” entertaining Yippee troops journeying from across the nation to protest the Democratic caucuses for president in a country perennially bisected down the middle. The Five, along with Phil Ochs, and The Fugs, were one of the few promised bands to show up, managing to play an incendiary set (captured on film by the FBI) before tear gas and flailing police brutality took Black To Comm to a more ominous mayhem.

Among those swept up in the melee is Fred. On his twentieth birthday, he is in a downtown Detroit jail cell, charged with assaulting a police officer. When he’s released, there are crowds awaiting outside, cheering him, or so he thinks until he realises pitcher Denny McLain has just sealed his thirtieth win of the season for the Tigers. An ex-shortstop, Fred can appreciate one for the home team. It was a fantasy insurrection enhanced by hallucinogenic drugs and an overload of underestimation.

“LSD was the catalyst that transformed rock & roll from a music of simple rebellion to a revolutionary music,” Sinclair apotheosised, as the MC5’s notoriety began to generate national publicity. Increasingly the Five were promoted as a mouthpiece of the propaganda wing of the White Panther party rather than a cataclysmic rock and roll band; turvy topsy. It’s hard to fault their enthusiasm and idealism, barely out of their teens, swept up in the trench warfare of clashing ideologies. Was it music or message, jacked up or hijacked?

“MUSIC IS REVOLUTION,” Sinclair capitalised in December 1968. For the MC5, whose quest for purity of sound had begun non-denominational, they were about to discover that the overthrow of a system was going to take more than a major label record contract.

Lenny Kaye's book Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments In Rock & Roll is published by White Rabbit and available to order now. Kaye has also curated a Spotify playlist to accompany the publication.

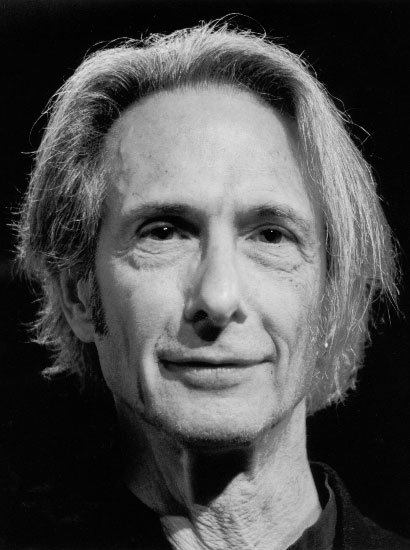

Lenny Kaye is an American guitarist, composer, and writer who is best known as a member of the Patti Smith Group and compiler of arguably the most influential compilation in rock'n'roll history, NUGGETS.