Paul Kantner: a tribute to Jefferson Airplane's cosmic guide

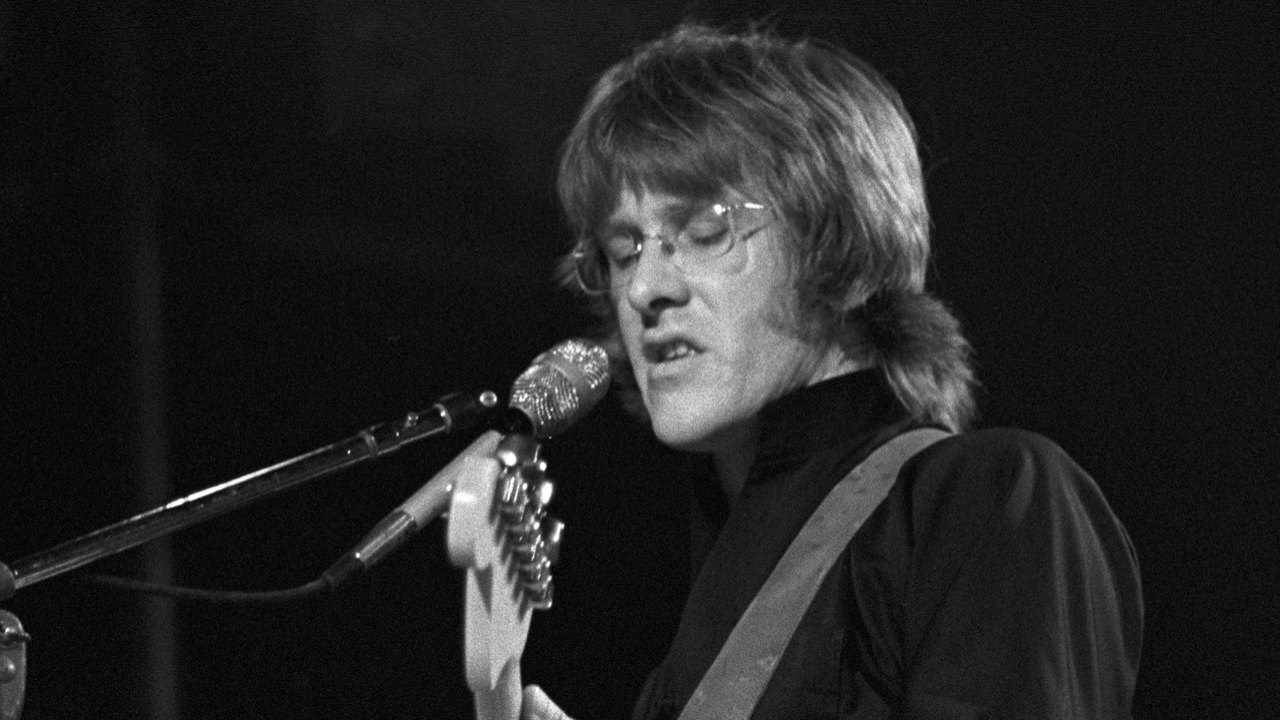

The life and times of Jefferson Airplane's Paul Kantner, space explorer, a.k.a. Baron Von Tollbooth

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

News that Paul Kantner died yesterday aged 74 will hit lovers of West Coast counter culture psychedelic rock harder than most. After Jerry Garcia, Paul Lorin Kantner was arguably the most significant figure in that scene.

It would be an immense stretch of the truth to say that Kantner and his band Jefferson Airplane embodied the concept of peace and love. The Airplane were a notoriously quarrelsome set of individuals who were more interested in challenging authority, the drug laws in America and the abiding feeling that Uncle Sam was instigating an Us vs Them police state in which it was a crime to be young and idealistic.

Kantner was the one who made them stick to their principles. He guided their important early song, The Ballad of You and Me and Pooneil, instigating solo space for bassist Jack Casady and revelling in Jorma Kaukonen’s fiery feedback. His tracks Watch Her Ride and the LSD anthem Won’t You Try/Saturday Afternoon encapsulated the experimental and trippy, celebrating the possibilities for embracing the anarchic lifestyle espoused by Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters.

Amidst all the anarchy, the Jefferson Airplane were caught up in the most notorious event of the decade on a stage: not Monterey or Woodstock, where they performed with distinction, but the Altamont Speedway concert. Kantner recalled the event where an audience member was stabbed to death while the Rolling Stones played as “pretty demonic. Not the Stones – they were pretty tame, actually. One of the main things we learned as a band in those days was not to be the headliner. Nowadays you can be the headliner, but in those days the headliner went on last – which usually meant four o’clock in the godawful morning, with eight people awake, in those big monster shows. Everybody burned out on sun, drugs and beer and each other and dirt…”

Having been brought up in Bill Graham’s more intimate Fillmore halls Kantner became massively disillusioned with stadium rock, which he saw disappearing into a corporate maelstrom. “Horrible things in stadiums that are just depressing to even think about. That is all an outcropping of that original search for that lack of self-control, up to a point, in a fairly uncontrolled area, be it Golden Gate Park at the Be-In, or the Fillmore.”

Not that Kantner was a hippy dreamer. Like David Bowie, yes, he was heavily into Science Fiction and space travel and translated his obsessions into the album Blows Against the Empire, a concept album about leaving this planet that predated Star Wars (George Lucas was a cameraman at Altamont, and the Jefferson Starship featured in the Star Wars Holiday Special TV spin-off in 1978). Dr. Stephen Hawking currently takes these ideas seriously.

Given the paranoia surrounding the Vietnam War and the Cold War Kantner’s lyrics (co-penned with Stephen Stills) for the Volunteers album song Wooden Ships would become recognised as his masterpiece. Neil Young picked up the same idea and ran with it on the title track for After The Goldrush. The martial beat and nuclear apocalyptic scenario of Wooden Ships had enormous resonance at the time ,and can be seen as a partial influence on various literary efforts, notably Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker novel.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

While Kantner and his lover Grace Slick became a cause célèbre couple in the early 1970s – the birth of their daughter China was fodder for glossy socialite magazines – they were never the best behaved, nor even married. Rolling Stone christened them “the psychedelic John and Yoko” and friend David Crosby referred to the pair as Baron Von Tollbooth and The Chrome Nun, a moniker they gleefully used for an album of the same name that featured various members of the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service bassist David Freiberg.

The formation of Jefferson Starship should have maintained Kantner’s science fiction leanings but they became a vehicle for a homogenised radio friendly rock and roll MOR that he despised. He wasn’t alone in that, and Kantner returned to writing his novel The Empire Blows Back, a stygian and dystopian fantasy in which telepathic children roamed the Australian outback pursued by global government agencies determined to steal their powers.

The accompanying album Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra (featuring Slick, Garcia, Casady, Scott Matthews, Ron Nagle, Freiberg and guitarist Ronnie Montrose) struggled to put across the idea of computer assisted telepathic amplification technology and was broadly slated by the music press although esteemed science fiction writers Kurt Vonnegut and Robert A Heinlein gave it their blessing. That pleased Kantner more than any snotty put down.

If this was Paul’s final studio solo proper, it wasn’t his last foray into recorded endeavours. The KBC Band album (Kantner, Marty Balin, Casady) came with the motto: “Life is a test. Had this been a real life, you would have been told where to go and what to do.”

His career was punctuated thereafter by spells of ill health, including a series of occasionally reported heart attacks. He’d recovered from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1980 but the attack that laid him low in 2015 when he was 73 was an 11th hour wake-up call even if he returned to the stage with the Starship for the Airplane’s 50th Anniversary show.

In so many ways Kantner was a catalyst rather than an obvious front man. He led from the side with his rhythm guitar and his ever-committed performances. Never really a singer, nor even the Airplane’s most accomplished musician (that title belonged to future Hot Tuna maestros Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady) he was the grit in the oyster.

Grace Slick’s heartbroken tribute, “Rest in peace my friend. Love Grace,” is poignant indeed. Marty Balin is typically generous when he writes, “So many memories rushing through my mind now. So many moments that he and I opened new worlds. He was the first guy I picked for the band and he was the first guy who taught me how to roll a joint. And although I know he liked to play the devil’s advocate, I am sure he has earned his wings now. Sai Ram, ‘Go with God’.”

Ride the music on your wooden ship, Paul Kantner. Free and easy.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.