"It was like Dorothy landing in Oz" - what happened when Alice Cooper went to Los Angeles

Once upon a time, a garage band from Phoenix moved to LA and became Alice Cooper, with a little help from Frank Zappa, a dark alter ego and... West Side Story

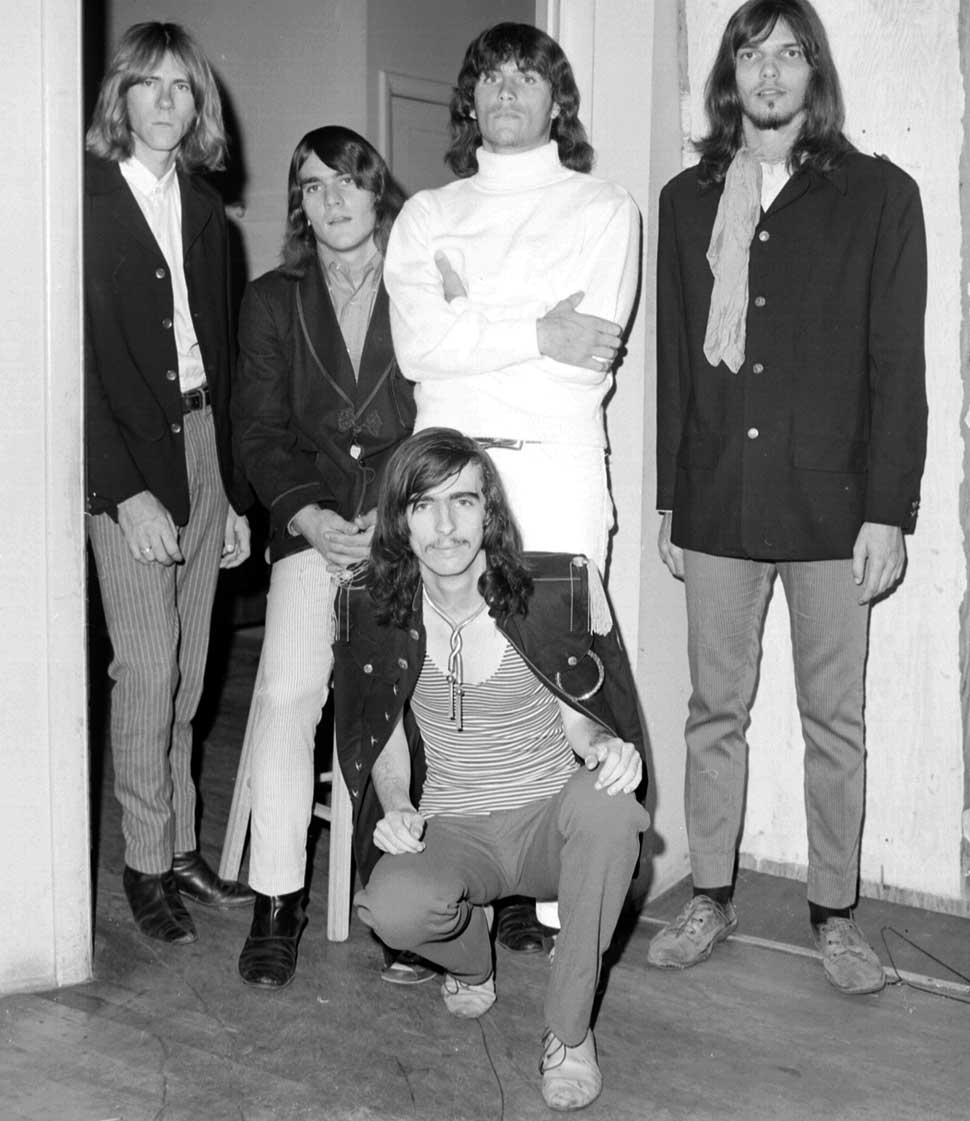

In 1967, a year after graduating from Phoenix, Arizona’s Cortez High School, The Spiders – an Anglophile garage band based around cross-country lettermen Vince Furnier (vocals), Dennis Dunaway (bass) and Glen Buxton (lead guitar) – grew tired of being big fish in a small pool. After they brought in rhythm guitarist Michael Bruce, their second single, Don’t Blow Your Mind, had given them a local hit, reaching the dizzy heights of No.11 in Tucson. They were on the radio and in demand on the South-West club circuit, but Tinseltown beckoned.

“It was like Dorothy landing in Oz,” Dennis Dunaway recalls of the band’s arrival into Los Angeles. “We were young, had a vision, so just jumped in a van and drove there.”

With no money for a hotel, the quintet (initially completed by drummer John Speer) slept in Griffith Park. As dawn broke they begged stale sustenance from a truck-based sandwich vendor as he binned his previous day’s stock.

“We pushed Vince to the front, as he was the skinniest and most pathetic-looking. That night we walked down Sunset Boulevard and it was unbelievable; The Byrds were here, The Doors there, Love… We’re like: ‘Okay, we’re gonna have to start all over. We’re gonna have to up the ante to compete here.’”

The band were able to gain a foothold in the city thanks to, Dunaway recalls, “this guy named Doke, who worked for [film star] Tony Curtis. He had a little apartment and said we could stay. We got some mattresses, covered the floor with them at night so we could sleep, and the windows during the day so we could practise. Doke was too nice to ask us to leave, but we finally got some gigs and got our own place.”

The band moved, somewhat incautiously, into the [US soul group] Chambers Brothers’ old place in Watts (“[we were] the only white guys in the neighbourhood”), before finally settling in the decidedly more sedate Topanga Canyon.

Meanwhile in Berkeley, another Phoenix band, the Holy Grail, were similarly trying to break into California, but their drummer, Neal Smith, was becoming disillusioned at the extent of his bandmates’ drug use. As destiny would have it, while Smith was visiting Dunaway in LA, John Speer announced that he was leaving.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“John quit, Neal was there,” says Dunaway. “It wasn’t pre-planned, it just happened.”

With Smith in place, the band – and vocalist Vince – adopted the name Alice Cooper, and acclimatised their lifestyle to that of the burgeoning Los Angeles freak scene. While San Francisco was the centre of the blissed-out hippie scene, LA’s counter-culture was defined by significantly more militant freaks, and the Coopers recognised kindred spirits.

Their regular Cheetah Club performances soon found favour with local scenester Vito and his ever-present harem of young girls. Their downstairs neighbours were Rushton Moreve of Steppenwolf and his aptly named girlfriend Animal Huxley (novelist Aldous Huxley’s ‘wild’ granddaughter, who wasn’t averse to smashing guitars when roused).

The GTOs (Girls Together Outrageously), an all-female band of Frank Zappa associates, befriended the Coopers.

“Everybody says they did our look,” says Dunaway. “But we used to shop in the women’s section of the thrift stores back in Phoenix. That was our look. When we got to LA we asked the GTOs: ‘Where’s the thrift stores?’ They showed us, but didn’t style us. [GTOs member] Miss Christine ratted Alice’s hair and dyed it blond, though. Tiny Tim was really popular in LA at the time, and everybody kept calling Alice Tiny Tim, so we decided to change his hair colour.”

As the band’s notoriety spread, an audition was arranged with freak kingpin Frank Zappa, with a view to signing to his Straight Records label, for which they famously arrived 12 hours early at 7am. An impressed Zappa immediately signed them to a three-album deal.

But all was not strictly as it seemed. Dunaway: “By the time Frank agreed to put us on his label, his manager had already told him: ‘We can’t afford to do this.’” Slicing expenses to the bone, the band’s Pretties For You debut album was recorded in just two nights, working “from midnight to sun-up”. “We didn’t have time to work with Zappa. We basically went in and he said: ‘Start playing, we’re gonna record it.’ We didn’t even realise what was happening. We were still warming up when he said: ‘Okay, we’ve got about half the album.’

"Then Frank got sick and didn’t show up for the second day. [Zappa’s manager] Herbie Cohen decided to produce the record, showed up and proceeded to fall asleep on the couch. So we were like: ‘What are we gonna do?’ We didn’t know how to work any of the equipment. Anyway, Ian Underwood [the Mothers Of Invention’s woodwind and keyboard player] came to our rescue. The only reason Pretties For You sounds as good as it does – which isn’t that good – was because of him.”

Pretties For You may have been flawed, but it had sufficient legs to take it into the US album chart. Its modest commercial success gave the band the option to return to the studio and make a second record. But Zappa’s management didn’t want to spend another cent on Alice Cooper, so they set an implausibly tight deadline within which to deliver the record, wholly expecting the Coopers to buckle under the pressure and fail.

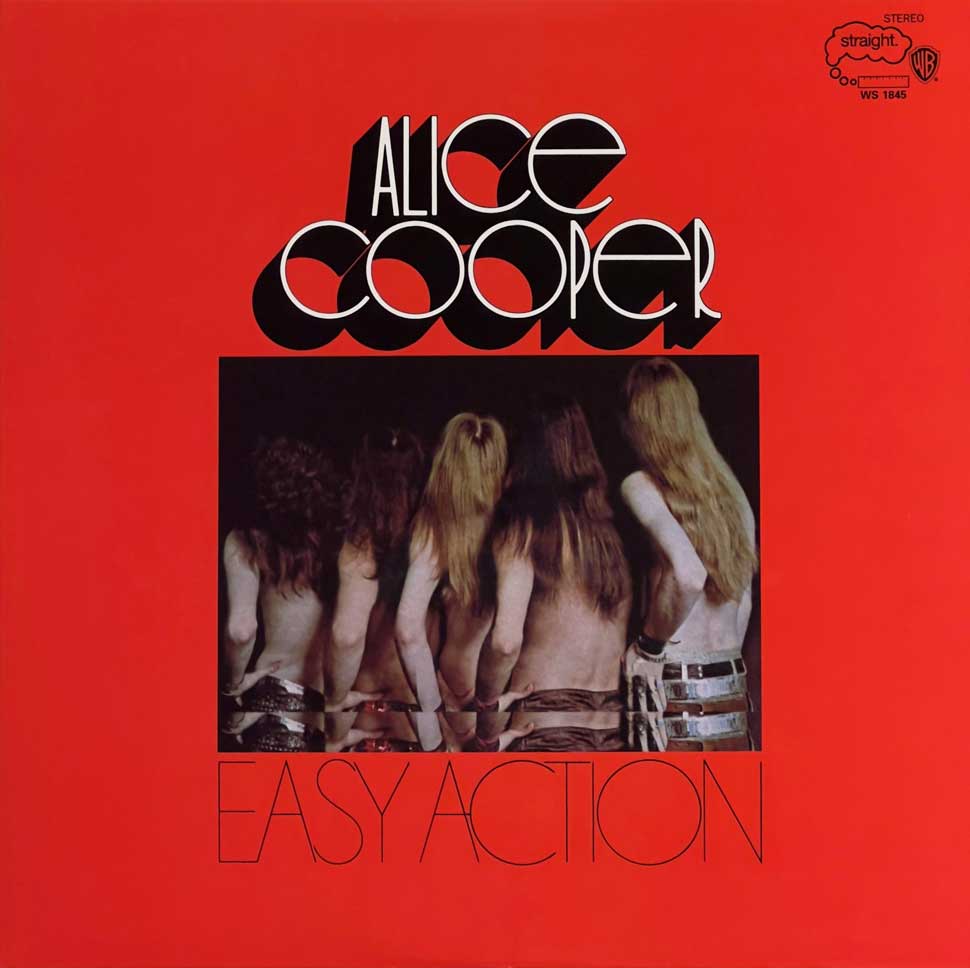

Creatively ambitious, the Coopers needed time to hone material, but without access to a rehearsal room they were forced to pull together compositions at sound-checks and write in the car between gigs. Consequently, as they reconvened in Sunwest Studios in November ’69 to record the album that would become Easy Action, they were far from prepared.

“We were only about a third of the way to being ready to record an album,” says Dunaway. “If we’d had a rehearsal room and enough time to get the songs in shape, Easy Action would have sounded more like [next album, in ’71] Love It To Death than like an unprepared free-for-all.”

Just as with Pretties For You, much of Easy Action’s material was wilfully complex. But with reality biting, the band realised they had to buff up their outsider art with just enough commercial sheen to secure themselves a wider audience.

“In my opinion, Pretties For You was too commercial,” Dunaway says, laughing, “I wanted to go even more abstract.”

But the band was a democracy. Every musical idea, lyric, even how the band dressed had to be voted on, with every collective decision passed unanimously. Ultimately, on this occasion the practical won out over the surreal. “After Pretties For You we had a meeting and said: ‘This isn’t putting any food on our table. We need to start learning how to write songs that are more relatable to people.’”

Back in high school, when Alice was still Vince, he and Dunaway were both in the same art class. When they formed their garage band, they wanted to incorporate artistic ideas in order to stand out from the crowd. From the beginning, their live shows were challenging: wilfully chaotic, ever-changing, theatrical.

Initially, Vince wasn’t terribly comfortable on stage. In their earliest incarnation, when the band performed covers he’d channel the songs’ original singers. But on original material he seemed lost. He would even face the back of the stage rather than the audience. Until it was suggested he sing each song as a different character.

One particular character, a dark one that he’d inhabit during Fields Of Regret, became a firm fan favourite. So more songs were written specifically for this character and, as it fleshed out, it gradually metamorphosed into the alter-ego inhabited by Vince Furnier to this day – the character of Alice Cooper. It was dark, sinister, outrageous. And it was relatable.

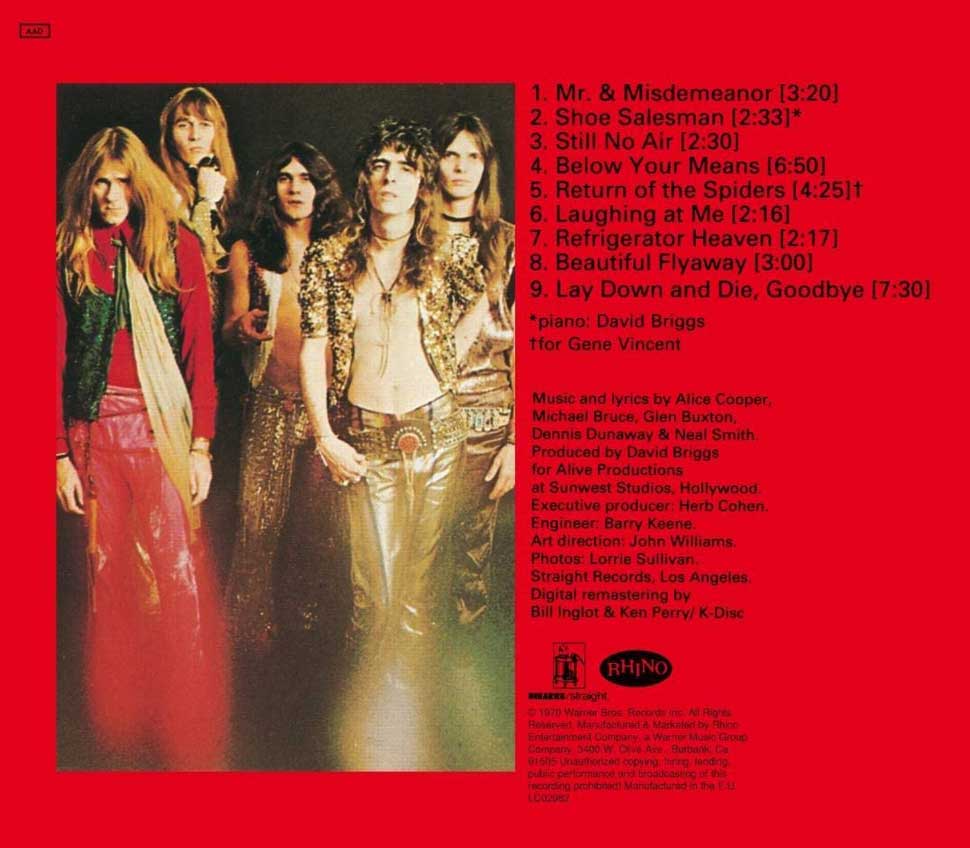

While the quintessential Cooper character found on Easy Action’s most enduring tracks (Mr & Misdemeanor, The Return Of The Spiders) would develop a commercial allure of its own with the passage of time, a more immediate form of commerciality was sought in the album’s single. Shoe Salesman, an inoffensive, piano-driven ditty as market-targeting and twee as anything one might expect of pre-Space Oddity Bowie, saw the album’s unlikely producer David Briggs (renowned for his work with Neil Young) being more hands-on than at any other point during Easy Action’s recording.

“He was one of those Topanga Canyon guys with the tan fringed jacket,” Dunaway recalls. “Now the hippie side of LA and the freak side of LA were like oil and water, so when we walked in he didn’t like the way we looked, didn’t like our humour. Usually when we turned on the charm we’d win anyone over, but with him it wasn’t working. He didn’t like us.”

Openly referring to the band’s music as ‘psychedelic garbage’ didn’t exactly endear Briggs to his charges as the fraught sessions continued. But out of the desperation came a fair few moments of inspiration. Following the quintessentially Alice snarl and swagger of Mr. & Misdemeanor, Easy Action continues with the relatively restrained Shoe Salesman (Les Paul fan Glen Buxton demonstrating his jazz chords as producer Briggs carries the tune on piano).

While gestating Easy Action’s material, few outside influences penetrated the quintet’s 24/7 songwriting mind-set other than (LA contemporaries) The Doors, radically experimental modern classicist Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Pink Floyd (who’d been the Coopers’ house guests during the West Coast leg of their debut US tour. Deep thinker Dunaway thought he’d found a kindred spirit in Syd Barrett as the taciturn Floyd wunderkind sat patiently, appearing to be hanging on his every word, until realising he just happened to be sitting in Syd’s field of vision while he gazed into space).

Another enduring influence that united the entire band was Leonard Bernstein, especially his music for the musical West Side Story. Easy Action took its title from the musical’s Cool, and third track Still No Air (originally written for Pretties For You) incorporates a snippet from The Jet Song (which the band returned to again for both Gutter Cat vs The Jets and Grand Finale on 1972’s School’s Out album).

Vinyl side one concludes with Below Your Means, an extensive composition with a similar complexity to (’71 Alice album) Killer’s Halo Of Flies: veering off in surprising directions, its intrinsic theatricality is more musical theatre than prog).

Shoe Salesman’s B-side, Return Of The Spiders, opens side two. Dunaway’s unmistakable bubbling Hofner bass (on loan from The Cowsills) locks into Neal Smith’s rolling Wipeout drums (the classic Surfaris instrumental was the first thing Smith played with the band) on a brooding intro that bursts into Alice’s opening ‘Stop, look and listen’ lyric which, according to Dunaway, was “aimed at those people who, when we did a gig, lined up at the exits to get out as fast as they could”.

Laughing At Me – based on a germ of an idea later used to infinitely greater effect on the Killer album’s Desperado – is followed by Refrigerator Heaven (not a prototype for the freezer compartment necrophilia of solo Alice’s ’75 Welcome To My Nightmare favourite Cold Ethyl, but rather for the suspended animation of Dunaway’s recent mini-movie Cold, Cold Coffin). The McCartney-esque Beautiful Flyaway, featuring rhythm guitarist Michael Bruce on lead vocal, acts as a calm-before-the-storm prelude to epic set-piece closer Lay Down And Die, Goodbye.

The band were still intent on writing material for Alice’s dark character to inhabit when they played live (they finally perfected the process with Dunaway’s Black Juju on 1971’s Love It To Death) and LD&DG, with its extended opening instrumental section and abstract central sound collage, was an early attempt to provide an appropriate soundtrack to accompany Alice doing “creepy things” on stage.

Easy Action was released in March 1970 to largely savage, baffled reviews. It came in a scarlet sleeve adorned with a shot of the band photographed from behind (Neal Smith’s idea; unsurprisingly, considering he had the most significant length of hair to show off).

Soon after Easy Action’s complete failure to set the charts alight, the Coopers (who had so far also survived rolling their van over three times on the LA freeway – with them, all their equipment and a washing machine in the back – as well as ingesting copious hallucinogens, and a rather unfortunate on-stage incident with one of Glen Buxton’s stunt chickens) decamped from LA to Detroit with, according to Dunaway, “our tails between our legs”. “There were rumours our management had bounced too many cheques, there were threats and there were crazy people.” But they were always welcome on the road.

Ultimately settling in the Motor City, the band continued writing, building on Pretties For You and Easy Action’s learning process, cross-fertilising with The Stooges and MC5 and gigging hard. “We’d play Toledo and they’d try to kill us, we’d play Saugatuck and they’d try to kill us. We were used to the cowboys in Phoenix. But this? This was tyre irons.”

Two years later, Alice Cooper were the most notorious, highest-grossing band on the planet.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.