Is the guitar hero an endangered species?

...Or just a radically changed species? Rock’n’roll’s evolution has gone from Chuck to Page, EVH to Satch to Slash… But what do today’s six-string wizards look like? Classic Rock investigates

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

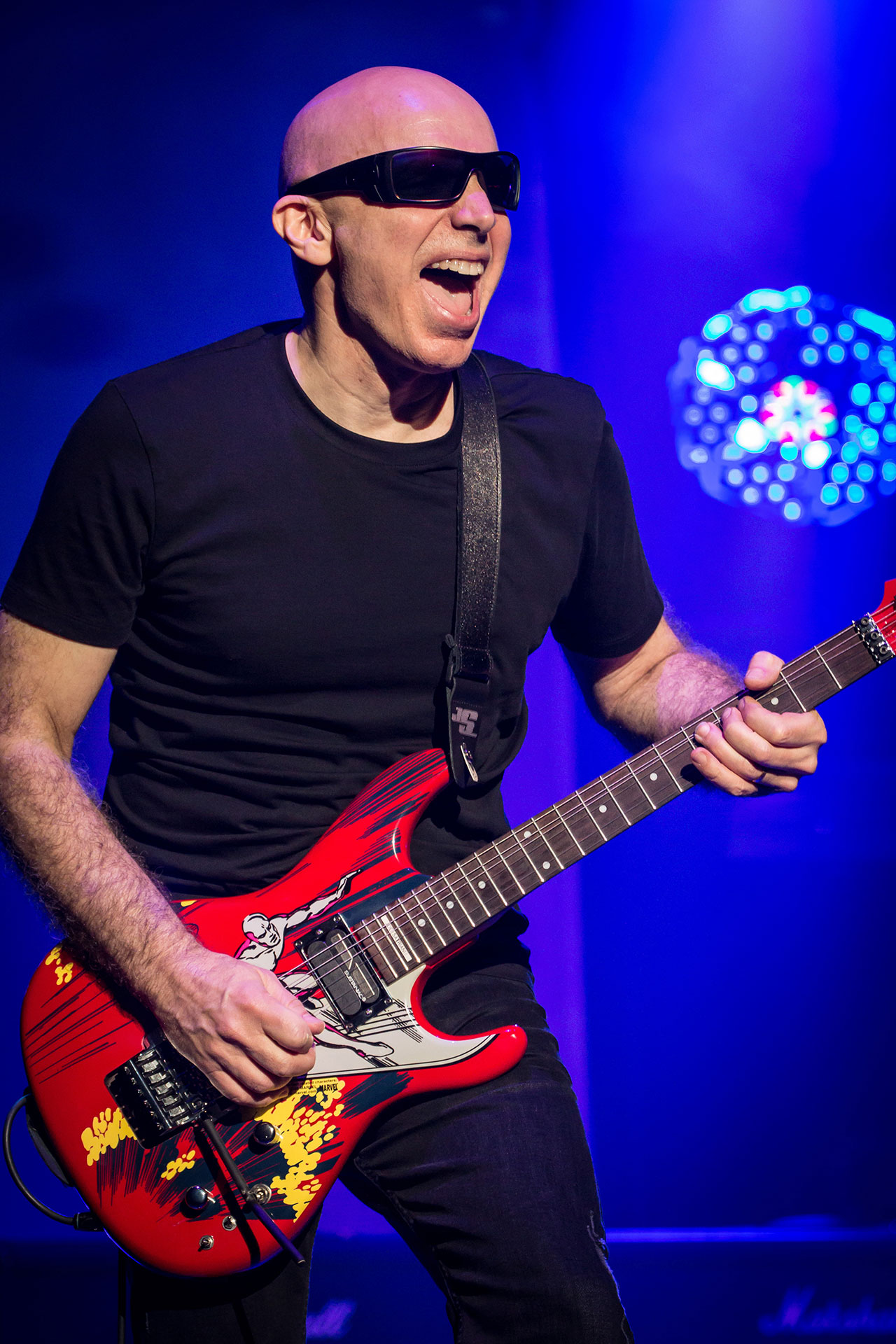

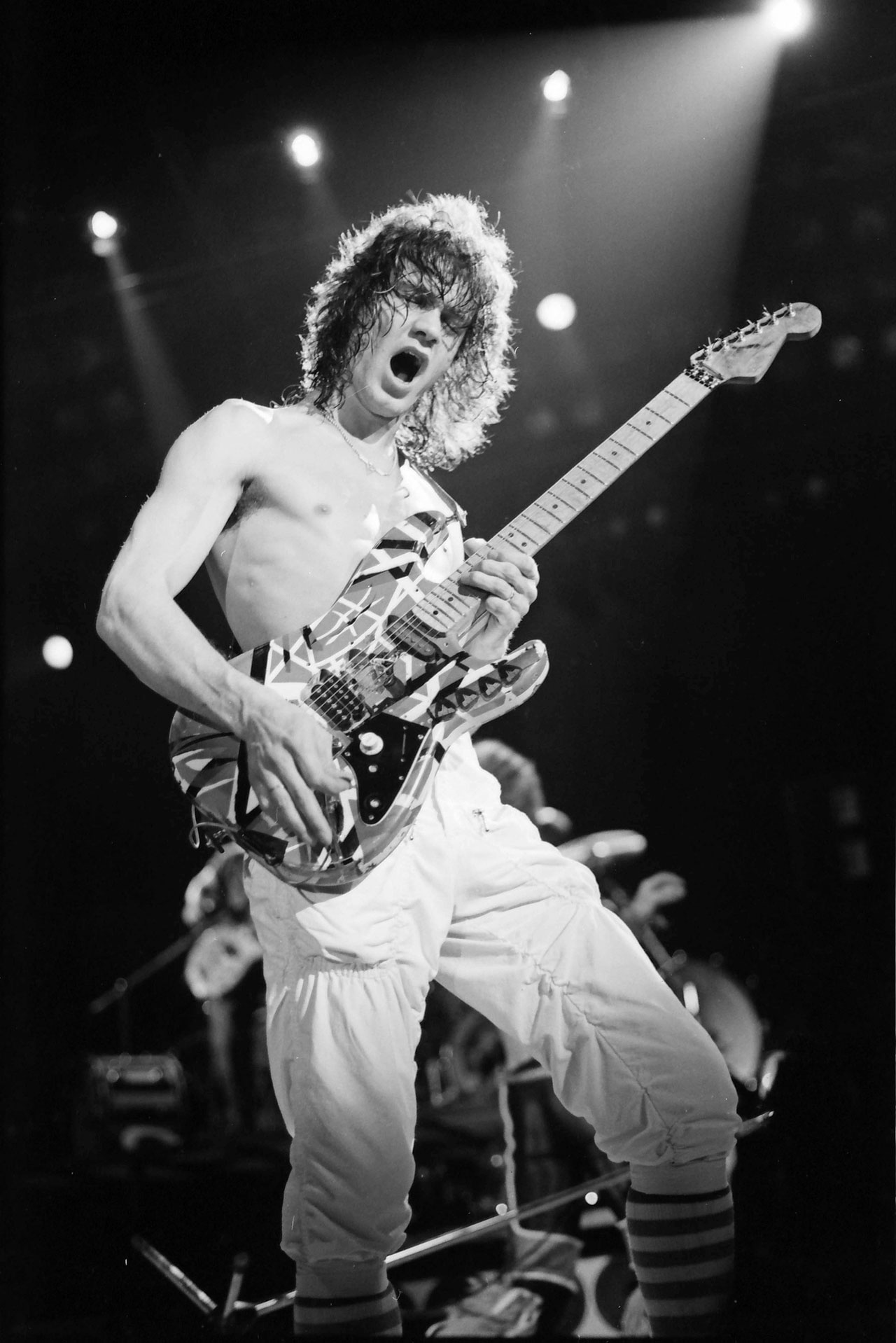

Rock’n’roll is built on guitar heroes. Bassists, singers and drummers are also important, of course, but when it comes to major benchmarks in rock history it’s the lead guitarists that carry the most weight. Chuck Berry was key, as were Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Eddie Van Halen. In the 80s, Steve Vai, Joe Satriani and Yngwie Malmsteen took it up a level with fusion-addled guitar heroism, driving instrumental rock to the next level: distinctive figures playing distinctive music.

Today, more people can pick up a guitar than ever before, and they do so in large numbers, if the colossal proliferation of new music (and guitar tuition videos on YouTube) is anything to go by. But the question of who our new guitar heroes actually are is a little more subtle.

In the 70s and 80s, guitar heroes were easily identifiable. Bigger fish, usually in a smaller pond, Jimmy Page, Slash and company were striking characters who, alongside all the virtuosity, wielded their guitars like wizard staffs and retained an aura of debauchery.

In 2017, with an ever-increasing pool of influences at their disposal, a new breed of axe-wielders has emerged – incredibly disciplined, fuelled by increased technology and held to account by social media. It’s an odd mix of liberation and hitherto unseen pressure that they have to contend with.

“I think each generation wants a guitar hero,” says Jason Sidwell, Senior Tuition Editor on Guitar Techniques, Guitarist and Total Guitar magazines. “And many people would attribute the guitar hero within a classic rock environment because it’s historically the most mainstream genre for a guitar player to be in. Things are much better than they were in many ways, but also more closed.”

So what does a guitar hero – or an aspiring one – even look like in 2017? Not a singer who plays as well, such as Lzzy Hale, or an excellent band player, but someone who pushes the guitar to the front of the equation? Remarkably fresh-faced, it seems, and often paired with icons eager to help foster the next generation of six-string stars. Australian-Greek sensation Orianthi, now 32, started playing when she was six, and at 15 performed with Steve Vai, before playing with Santana when she was 18. For 18-year-old Quinn Sullivan, it was blues legend Buddy Guy who took the youngster under his wing. Quinn was eight years old at the time, and in the coming years it led to a string of US chat show appearances.

“That’s how people have known me in the media,” Sullivan tells Classic Rock. “So the aim is to now do my own stuff, my own tours and show people I’m not just Buddy Guy’s little prodigy.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

For Oxford-born gunslinger Aaron Keylock – who started playing at local jam nights when he was still in primary school, and was headlining London blues clubs aged 12 – it was his dad’s classic rock records and the lure of the stage that drew him to the guitar.

“I’ve always tried to get out and play live and find my sound as a performer that way,” says Keylock, who’s just released his debut album Cut Against The Grain. “But there’s a lot more people getting into different ways of learning, rather than going down one route because it’s what you have to do if you want to play.”

Dorian Sorriaux, aged 16 when he joined Sweden-based rockers Blues Pills, got off to a similarly organic start. Playing with much older musicians back home in France made it easy for influences like Peter Green and Paul Kossoff to weave into his style.

“I used to jam any chance I got,” he says. “There was a jam every Thursday evening in my home town when I was about thirteen, and it was only old people at the bar, but I’d always go there. It was a great way to learn. And I learnt a lot with DVDs from guitar magazines – DVD lessons.”

With so much tuition available, there’s the potential for guitarists to become more studious earlier on. In this respect, a lot hasn’t changed.

“The thing is, they [new guitarists] wanna learn how to be good,” chuckles Joe Satriani, who taught Steve Vai and others, before becoming a guitar star in his own right. “There’s a sort of a phantom quality that they pick up on… the young musicians out there are smart, they have good taste and they know what they like, and they expect to be as good as those people that they see out there making music. So I don’t think that’s really changed.”

Not that determination doesn’t get skewed sometimes. Jim Clark, deputy head of guitar at BIMM (see www.prorockguitar.com for lessons), thinks single-minded graft can actually compromise artistic flair.

“There’s always a group of super‑hard-core guys who take it very seriously, sometimes to the detriment of creativity, treating it like working out in the gym – playing exercises but not music,” says Clark, discussing his more recent guitar students. “I remember a potential student at an open day saying he used to feel guilty if he did anything other than practise guitar. But making good music, like any art form, should come from inspiration, whether that be a challenge in your life, having your heart broken, travelling, seeing a great movie or reading a book.”

Perhaps one of the most pivotal differences between guitarists of today and those of the past is equipment. Present-day players have access to more stuff than ever before: more affordable guitars, gear and home studio equipment, plus online lessons, guitar DVDs, millions of YouTube videos homing in on virtually every solo and lick ever written… It’s opened up the Age Of Comparison.

The 21st-century guitarists, teachers and aspiring stars have more means than ever to emulate the legends that have come before them, as well as those that surround them today. They have the gear to work with, and a constant stream of examples online – of both the real deal, and dazzling imitators.

“It reminds me of this quote, attributed to Theodore Roosevelt: ‘Comparison is the thief of joy,’” Satriani says. “When you go on YouTube and you see eight thousand guitar players from every country in the world that can all play the same technique that was made popular yesterday by some guitarist on a pop song, why would you continue? Whereas that enthusiasm you get from just enjoying doing it yourself, that gets robbed when you open yourself up for that comparison. Is that the energy that’s going to force musicians to try harder? Or is it energy that kills the spirit? I vacillate on that one.”

Not that all guitarists and aspiring stars are overwhelmed by this, of course. “I write a lot with my iPhone,” says Sullivan. “I make notes of lyrics and ideas, I use it for voice memos and recording guitar parts, and I’m always on YouTube searching for different things. We’re in 2017 now – it’s definitely a faster kind of movement.”

Without considered use, however, online ‘guidance’ could be detrimental to the players’ progress. While the web is peppered with bona fide instructors and Yoda-esque purveyors of guitar wisdom (Marty Schwartz, Tom Quayle and John Wheatcroft, to name just three), according to Clark, an awful lot of core building blocks get missed by less credible YouTube noodlers.

“Many budding guitarists can jump onto the internet and learn to effectively play by numbers,” he says, “very often under the guidance of self‑professed ‘industry experts’ who present well to a camera, but have little to no actual experience of working in the music industry. On the surface, after five hundred takes of a video in their bedroom, they present themselves as having an almost virtuosic skill set. Which is actually just a bag of tricks with very little substance, which would be immediately apparent to a professional player.”

It’s a set of pressures and conflicting sources unexperienced by previous generations. What’s more, it’s all compounded by the fact that the likes of Van Halen were innovators as well as virtuosos, whereas now there’s comparatively little new ground left to break. And while players like Brian May, Eddie Van Halen and Jimmy Page were essentially household names, today’s virtuosic guitarists are less likely to move beyond niche markets.

“To make that kind of impact again you’d need a guitar player at the front of One Direction or Little Mix or someone like that,” Sidwell suggests.

Arguably, instrumentalists – soloists or in bands – were all doomed in the post-MTV world. “Music was changed forever when it became more visual,” reasons Satriani. “The camera really liked people looking into the lens and singing. That kind of did every instrumentalist in to a large degree, and changed the whole scene.”

“After Nirvana hit in the nineties, guitar solos were almost outlawed outside of the small hardcore shredder camp,” adds Clark, “which was probably the start of a more niche-driven community of players trying to carry the torch, which grew bigger with the advent of the internet.”

So which players are standing out in this niche community, beyond the YouTube shred warriors, for whom playing the guitar can seem more like a competitive sport than an art form? And with so much rock ground already covered, how does a 21st-century guitarist stand out? Sidwell suggests it’s about having more versatility or more vocabulary, in the manner of someone alarmingly able and inventive, such as Tosin Abasi, guitarist with instrumental rock trio Animals As Leaders. He’s a dazzling player, with many ‘guitar hero’ qualities (good looks, jaw-dropping skills, a certain amount of swashbuckling delivery style), but unknown to many outside the dedicated guitarist world.

“He’s playing eight strings instead of six, he’s using very modern technology, he’s got a degree of jazz vocabulary, he’s got the chromaticism of modern metal, and a classic rock background,” Sidwell explains. “There’s generally the idea of the white, Anglo-Saxon shred rock guy, so it’s very refreshing that Tosin is making a little dent in some way. He will never make the inroads that someone like Eddie or Blackmore did, historically, and his band has no vocals, so instantly there’s a huge amount of an audience disappearing… So, in small letters, I would say he’s a ‘guitar hero’.”

And that’s the thing here: there are standout guitarists working today, bona fide artists occupying different styles and subgenres. In bluesy circles, the likes of Joanne Shaw Taylor have been cultivating quietly devout followings with burgeoning arsenals of killer licks and riffs. Shaw Taylor’s last album Wild hit the Top 20 in the UK album charts last year, and this November she headlines the Royal Festival Hall: no mean feat for any rock artist in 2017.

“Guitarists like Tosin, Davy Knowles, Oli Brown…” says Satriani. “I’ve heard their records, I’ve seen them on stage repeatedly, and they’re the real deal. I think of those guys a lot; they’re doing their absolute best, they’re breaking their own ground and they’re doing it in a way that’s not turning their back on the past, which I think is really cool. They’re upfront with their influences but they’re hell-bent on being original.”

Beyond the music itself, however, comes the question of a guitar hero’s image. In the pre-smartphone, pre-internet era, the Pages, Claptons and Malmsteens of rock were able to retain a lot more mystery, even dress a certain way without the prospect of being monitored and judged by thousands of media outlets. Today, conversely, social media has reigned in the behaviour of rock stars and guitar stars. It’s this landscape that’s seen overwhelmingly skilled but far more down-to-earth players like Guthrie Govan, John Petrucci and Joe Bonamassa become especially revered. Aspiring guitar heroes – and people who ingest virtuosic guitar generally – appreciate different things in their icons.

“The internet brought the audience closer to the musicians, with Instagram and Facebook,” says Dorian Sorriaux. “There’s a bit more of a close relationship, so it makes it harder to be this godlike persona, because that mystery isn’t there. New guitar heroes are more down to earth.”

Perhaps this is spurred on by the fact that sex, drugs and rock’n’roll aren’t counterculture ingredients any more; or at least not in the way they once were.

“There isn’t the room for that now,” says Satriani. “There was back when rock was like the Wild West, and it added to the cachet of a band or musician. But it’s different now. It’s just more deadly for some reason, and it just comes off looking a little sad, y’know?”

“It’s more cleaned up now,” Sullivan agrees. “2017 is a completely different time to, say, 1973. I think everyone’s figured out how bad it [drugs, alcohol-abuse and so on] was, and how much it was actually killing people. I don’t mess with that stuff – I just concentrate on putting on a really good live show and making the best music I can make, and listening to as many people as I can.”

The truth is that guitar stars need to have their eyes on the prize if they’re to stand a chance of sticking out in today’s increasingly splintered, democratised music scene. The need to have a business head, or at least a clear head, is much greater today. Joe Bonamassa, for instance, has sold out enormous venues playing relatively traditional blues, and he’s done it all with a very sober public personality, but a fearsome work ethic – propelled, to a large extent, by producer/mentor Kevin Shirley. In a funny, understated sort of way, he’s one of today’s most successful full‑blown guitar heroes.

“He [Shirley] went, ‘Stop doing the pizzas, start wearing the suits, and you’ll see a change,’” Sidwell says. “And within about a year and a half, Joe went from being this relatively chubby, denim-clad bluesy guy that played killing guitar to a very sharp-looking blues statesman, and his career turned around.”

“Joe’s a great representation of what you wanna be when you’re thirty-five, thirty-six,” adds Sullivan. “He definitely paved the way for a lot of us young people.”

Not that all present-day fret kings and queens are squeaky clean. Ultimately, any guitar star in the right band can still adopt a more traditionally rock’n’roll image, whether it’s just for show or for real. Marilyn Manson guitarist John 5, Sidwell argues, falls into the latter category.

“Marilyn Manson is full of controversy and absolute madness,” he says. “And there was a point where John 5 was being used by almost everybody in LA. So there were deeply debauched moments with him, but I’ve never heard of Guthrie Govan doing anything like that.”

In a world increasingly viewed through screens, and addled by immense consumer choice, there’s less that unites people. Whether it was hair metal in the 80s or punk in 70s Soho, music has always had the capacity to bring people together – to create scenes over shared ground. Today, people have so much choice that the prospect of large groups bonding over a single thing is much less predictable. Under such circumstances, one could argue that the guitar hero has become an antiquated notion.

It’s not a totally split world, however, because brilliant guitarists still have one thing in common – the simple fact that they’re really serious about the guitar. From Jeff Beck listening to blues records in the 60s to present‑day players listening through their iPhones, the singular dedication to the instrument hasn’t really changed at all.

“I’ve been very fortunate to meet a lot of well-known guitarists and am lucky enough to call some of them friends,” says Clark, “and I can’t think of a single one who isn’t obsessed with playing the guitar, and most are so down to earth it’s bonkers.”

“You have to be honest with yourself about your playing,” adds Keylock, “and give it everything you’ve got and [laughs] throw your life away, basically!”

So let’s not give up on the guitar hero just yet, partly because there’s too much serious talent out there and partly because, for us fretboard fans, standout guitarists are inherently interesting. Even if they don’t become as famous as their predecessors, that doesn’t stop them mattering to the people who like them. If anything, it makes them feel all the more special, and more exclusive – quieter, often more relatable heroes, but heroes nonetheless.

And the potential for a new Hendrix or Page? With the passion and ability that’s out there, it has to be possible.

Good God!

The guitarist tracks from the past five years that prove Clapton isn’t the only six-string deity.

Orianthi - Voodoo Chile (Live)

Many have taken on this Jimi Hendrix classic, but few have done it with as much panache as Orianthi, a guitarist who gives her boyfriend, Richie Sambora, a run for his money.

Eric Gales - Good For Sumthin’

Eric Gales weaves between rock, soul and blues, with a touch of funkiness in his playing on this nod-to-Howlin’ Wolf winner. He does all number of delicious covers too.

Tosin Abasi (Animals As Leaders) - Cognitive Contortions

Tosin Abasi specialises in the kind of progressive guitar playing that actually pushes boundaries. Eye-popping, eight-string mastery at its most ambitious.

Aaron Keylock - Medicine Man

Keylock is 18 years old and plays swaggering, southern-laced bluesy rock à la Johnny Winter and Rory Gallagher. Check out new album Cut Against The Grain.

Oli Brown - Love Is Taking Its Toll (solo), and Hero (with his band RavenEye)

More recently Oli Brown has switched to a less solo-heavystyle with hard rockers RavenEye, but he remains a hugely talented axeman, rooted in the blues but ultimately very ‘now’.

Dan Patlansky - Backbite

South African Dan Patlansky plays blues, and then some. On record this is a sexy Kravitz-meets-SRV groove machine. Live, it’s that, plus a whole load of hands-free, string-grabbing whatthefuckery.

Joanne Shaw Taylor - Outlaw Angel

The Black Country maestro keeps getting better and better, and this dirty yet stylish piece of blues rock is a tasty piece of evidence. One to watch live.

Richie Faulkner (Judas Priest) - You’ve Got Another Thing Coming (Live)

The youngest member of Judas Priest looks good in leather and does mental shit with a guitar. Watch this solo, then pick up your jaw off the floor.

Guthrie Govan (The Aristocrats) - The Kentucky Meat Shower

No list like this is complete without this Amish-bearded, Chelmsford-born wizard. When he’s not playing with the likes of Steven Wilson, he’s melting minds with stuff like this.

Quinn Sullivan - Graveyard Stone

A sweet slice of soulful bluesmanship: ‘mature beyond his years’ is a real understatement. Check out his new album Midnight Highway.

9 tips to be a shredding master, from a real-life guitar hero

Polly is deputy editor at Classic Rock magazine, where she writes and commissions regular pieces and longer reads (including new band coverage), and has interviewed rock's biggest and newest names. She also contributes to Louder, Prog and Metal Hammer and talks about songs on the 20 Minute Club podcast. Elsewhere she's had work published in The Musician, delicious. magazine and others, and written biographies for various album campaigns. In a previous life as a women's magazine junior she interviewed Tracey Emin and Lily James – and wangled Rival Sons into the arts pages. In her spare time she writes fiction and cooks.