For a year Tommy James was bigger than The Beatles. Then the mafia ruined everything

With hits like Mony Mony and Crimson And Clover, Tommy James should have had the time of his life. Instead, he found himself robbed and threatened by the Mafia

On Saturday July 15, 1972 American rock legend Tommy James played a gig at the Paramount Theatre in Brooklyn. After the show, James and his friends from the group Grass Roots were driving to a party in their stretch limousine.

At exactly the same time, six blocks away, Thomas ‘Tommy Ryan’ Eboli, the acting boss of the Genovese crime family, was leaving his girlfriend’s apartment when an assassin pumped six bullets into his head and chest from point-blank range. That would be the last time he ever screwed up on a heroin deal.

The afternoon before, James and Eboli had been slapping shoulders in the off-Broadway offices of Roulette Records, James’s label. Roulette boss Morris ‘Moshe’ Levy looked on and smiled. High on drugs and dollar bills, everyone seemed hunky dory, unless you knew that Levy was ‘the Godfather of the Music Business’, a man so feared it was said there were six major crime families in New York City: Gambino, Genovese, Colombo, Lucchese, Bonanno and Moshe’s Roulette.

Levy was the nastiest person in show business. He had a radioactive personality inside a Teflon overcoat. Moshe made latter-day managers like Peter Grant and Don Arden look like wusses. If a major label had a problem with a distributor, they’d call up Mo. Radio stations playing hardball? Call Morris. For an appropriate fee, Levy and his accomplice, record exec Nate McCalla, would gather baseball bats and, whack!

Don’t mess with Morris. He was the architect behind the payola scandal that sank American DJ Alan Freed, the man who’d invented the term ‘rock’n’roll’. Back in the day, Morris’s brother Irving had been shot dead in a gambling dispute at the notorious Birdland jazz club, which they ran. Levy bided his time, then visited his brother’s killer and disembowelled him with a butcher’s knife.

Tommy James was a 19-year-old from Dayton, Ohio with a No.1 regional hit in Pittsburgh called Hanky Panky when he entered Levy’s orbit in 1966. Over the next six years James and his band The Shondells would give Roulette 23 gold singles and nine platinum albums. In 1968 James’s sales outstripped The Beatles in US. But as his book Me, The Mob And The Music makes plain, his relationship with Levy – the model for record mogul Hesh Rabkin in The Sopranos – was toxic from the very beginning.

“When I signed, I’d taken Hanky Panky to everyone in New York and got a yes. Roulette was the last place. Next day I got calls from all the companies – Columbia, Epic, RCA, Atlantic and Kama Sutra – and they said: ‘We gotta pass.’ Morris had phoned all the label bosses and told ’em: ‘It’s my fucking record. Leave it alone.’ And they did. It went downhill from there.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The James-Levy handshake had ‘love-hate’ tattooed on its knuckles. “If I’d gone to a corporate I’d have been a one-hit wonder,” James insists. “Roulette needed me because they hadn’t had a hit for three years, so they allowed us freedom. We did everything from writing the songs to designing the covers. It was a total education. Getting paid was different – that was like taking a bone from a Rottweiler.”

Morris Levy simply refused to accept the concept of royalties. If James needed money, his mentor gave him bundles of dollar bills in a brown paper bag. “Here’s $10,000, kid! Knock yerself out.” But royalties? Nah.

Shortly after James arrived in the city, Morris had an altercation with another of his artists, a crossover country pop star called Jimmie Rodgers, who had demanded payment for unpaid monies stretching back nine years. On December 20, 1967 Rodgers was found nearly dead beside the San Diego freeway, having been beaten to a pulp and left with a fractured skull. Rodgers testified that off-duty cops from the LAPD or the SDPD had assaulted him. But everyone knew the assailants were on Levy’s payroll. Rodgers was left with spastic dysphonia and no career.

“You took your life into hands when you asked Morris for royalties,” says James. Levy’s Roulette director friends were Eboli, Dominick ‘Quiet Dom’ Cirillo, Anthony ‘Fat Tony’ Salerno (on whom The Sopranos’ lead character is based) and Vincent ‘Vinny The Chin’ Gigante. His most terrifying ally was Gaetano ‘Corky’ Vastola.

Regarded as a stool pigeon, Vastola survived an assassination attempt by fun lovin’ criminal John Gotti, which resulted in the latter man’s incarceration. Years later Corky would be convicted, alongside Levy, of the assault of Philadelphia record retailer John LaMonte and sentenced to 20 years in jail. Morris died of cancer in 1990, before he’d served even a day in prison.

James led a charmed life. “I didn’t get any beatings, but plenty of threats and intimidation. You didn’t talk about what you knew,” he says. “Roulette was a social club for the Mob; they used it to organise illegal bank accounts and drug deals. Trailers were parked up all day unloading who knew what. I’m trying to have a pop career with this terribly dark and sinister story going on which could never be discussed.”

James’s talent kept him on Morris’s sweet side, as long as the hits were coming. Lucky, I Think We’re Alone Now, Mirage, Mony Mony, Crimson And Clover, Tighter And Tighter, Sweet Cherry Wine and the epic psychedelic switcheroo Crystal Blue Persuasion were massive. They made Levy millions. “Morris was a likeable guy. Like my father figure. But he was an abusive father. It was great to have him as my protector – ‘Don’t mess with me or I’ll get Morris’ – but he was also extremely fuckin’ scary.”

Once trafficking in hard drugs like heroin and cocaine took dirty money laundering to its peak, Levy’s psychotic nature ran out of control. “In 1971 a really horrible gang warfare broke out in NYC,” Tommy recalls. “The Gambino family was taking over the five families. It was right out of The Godfather. In six months over 300 wise guys got killed. Morris and Nate were implicated and took off for Spain – except they never left New York.

"When my album Draggin’ The Line came out I was left holding the Roulette bag. My lawyer told me flatly: ‘You must leave town. If they can’t get Morris they’ll go after who is making him money – and that’s you.’ I’m on the lam, so I went to Nashville and made a country record, My Head, My Bed & My Red Guitar, with Elvis Presley’s band.”

While Levy was indulging his evil appetites by taking the psychosis-inducing drug crystal meth, Tommy was, by his own admission, “a flaming asshole. I became a dark character. I got pretty nasty. I was very depressed at my situation. It was a dilemma. Either get out of my contract, which I could have done. Or stick it out, because I had so much success. I had plenty of money in my pockets from touring, TV and commercials; mechanical royalties… nothing.”

Sucked in and bled dry, Tommy enjoyed perks. The Roulette man bought him a farm near to his own spread in the Berkshires in upstate New York. The way he tells it, James sounds uncannily like Henry Hill, Ray Liotta’s protagonist in Goodfellas. “Morris was the most fascinating person I ever met. Without him, no Tommy James. He bet the farm on me, but it was a pact with the devil. He owned 3,000 acres of dairy in Gent, which meant he owned all the water. I’d go up on a Friday night and we’d get high. The wives would come Saturday.

"Everyone was blasted on brandy and grass. Once I asked him: ‘Why do you hang out with these people [the Mob]? They scare everyone at the company. Artists won’t bring you their master tapes because they’re so afraid.’ He laughs: ‘Tell you the truth, Tommy. These are the guys I came up with off the street. I known ’em all my life. It’s all I know.’”

If Levy had any sense of shame or guilt, he rarely showed it. “He told me how he killed the guy who gunned his brother down at Birdland. ‘I fucking took a knife and stuck it in his fucking stomach until his guts fell out.’ It was disgusting. And it was true.”

John Lennon was another visitor to Levy’s farm. In 1973 Levy and Lennon had become friends, but that didn’t stop the Roulette owner from serving the former Beatle with a plagiarism writ. Lennon’s 1969 song Come Together, on The Beatles’ Abbey Road album, began with the line ‘Here come old flat top, he come grooving up slowly,’ which had been appropriated from Chuck Berry’s 1956 single You Can’t Catch Me.

Levy owned the publishing on the original. He sued Lennon and won. As part of an ad-hoc settlement, Lennon gave Morris rough mixes of a rock’n’roll album he’d worked up with Phil Spector during his ‘lost weekend’ phase. The tapes were crap, but Levy put them out anyway, with Lennon’s permission, as a shoddy mail order LP called Roots, on subsidiary label Adam V111, named after his son.

Lennon was secretly delighted at the arrangement. He thought he’d make some easy money. Capitol didn’t see it that way and counter-sued Levy. The case dragged on for two years while Lennon, who was still getting off his heroin addiction by taking vast amounts of novocaine, slumped into his habitual depression.

During a particularly nasty stage in the trial, Levy invited Lennon to his farm, ostensibly to enjoy some quality rehearsal time for the unstable musician’s Walls And Bridges album. When Lennon arrived with May Pang (Yoko Ono’s replacement at that time), Levy threatened his life in no uncertain terms.

According to James: “May Pang told me what happened. It was very bad. Capitol had a shit fit but that didn’t bother Levy. He didn’t care for reputation or person. He had such balls. Lennon could easily have ended up in the East River. Capitol won, which annoyed Morris – they counter-sued because sales of Roots affected their own Rock’n’Roll release. That was a rare defeat for Morris, because he worked publishing. He was smart. He ripped everyone off. He’d put his name on songs he hadn’t written, then use them as album cuts.”

Even though he’d lost, Levy still won: he held publishing on two songs on Rock’n’Roll, and also had Lennon include Ya Ya on Walls And Bridges. “At one point people thought Morris had something to do with John Lennon’s murder outside the Dakota Building in 1980,” says James. “He didn’t.”

As the 70s began, James’s hit-run stalled. His dark character was becoming too prominent. “Taking drugs, I never stuck a needle in my arm. But that wasn’t because I was virtuous, I just liked the stuff I was taking better. Unfortunately the amphetamines made me psychotic.” James was in a state of extreme paranoia.

Convinced he was going to be assassinated, he acquired an illegal arsenal of guns. “I bought a .22 pistol, a .25 automatic pistol, a Browning .22 Magnum machine gun, a Marlin .22 with an octagon barrel, and a .32-calibre police pistol with an eight-inch barrel. I stockpiled ammunition. I started carrying a gun every time I went to the studio. I was also seeing a psychiatrist.”

Levy decided his cash cow was going nuts so he hired a Sicilian heavy called Dom to babysit him. James tried to extricate himself from Roulette but couldn’t. By day he hung out with the songwriters at Kama Sutra and at the Brill Building on Broadway, by night Morris dictated his social life.

“I didn’t hang with the guys in Little Italy so much, but I did go to the parties at Morris’s club, The Round Table. These parties would last four days. That’s when you knew he was connected. It was incredible. All the Mob guys were there; plus everyone from the Mayor’s Office, the Police Commissioner and the City Councillors. Funny thing was, despite the crazy shit they did, the Mob guys were pretty conservative. There weren’t a lot of broads coming out of cakes; just a lot of palms being greased and a lot of shoulders rubbed.”

James and his accountant, Aaron Schecter, made a final attempt to collect on mechanical royalties. “We visited the NY pressing plant that printed the record labels – there was only one – and had them count the numbers in front of us. I was owed between 30 and 40 million dollars. That ruse had never been done before, so Morris couldn’t argue. But he flat-out threatened us: ‘Fuck you. If you ever try and use that against me you will find yourself in the fucking river.’ He meant it."

Before he died, Levy sold his empire. All his masters and publishing under the Big Seven name went to EMI, while Warners bought Roulette, assigning the vintage material to their re-release outlet Rhino Records. Audits had to be done, and James finally clawed back royalties on some back catalogue. “Vast sums were still owing which I didn’t see. But although it ate me up, I’m glad I didn’t get the money. I might have destroyed myself. $40 million in the 80s?”

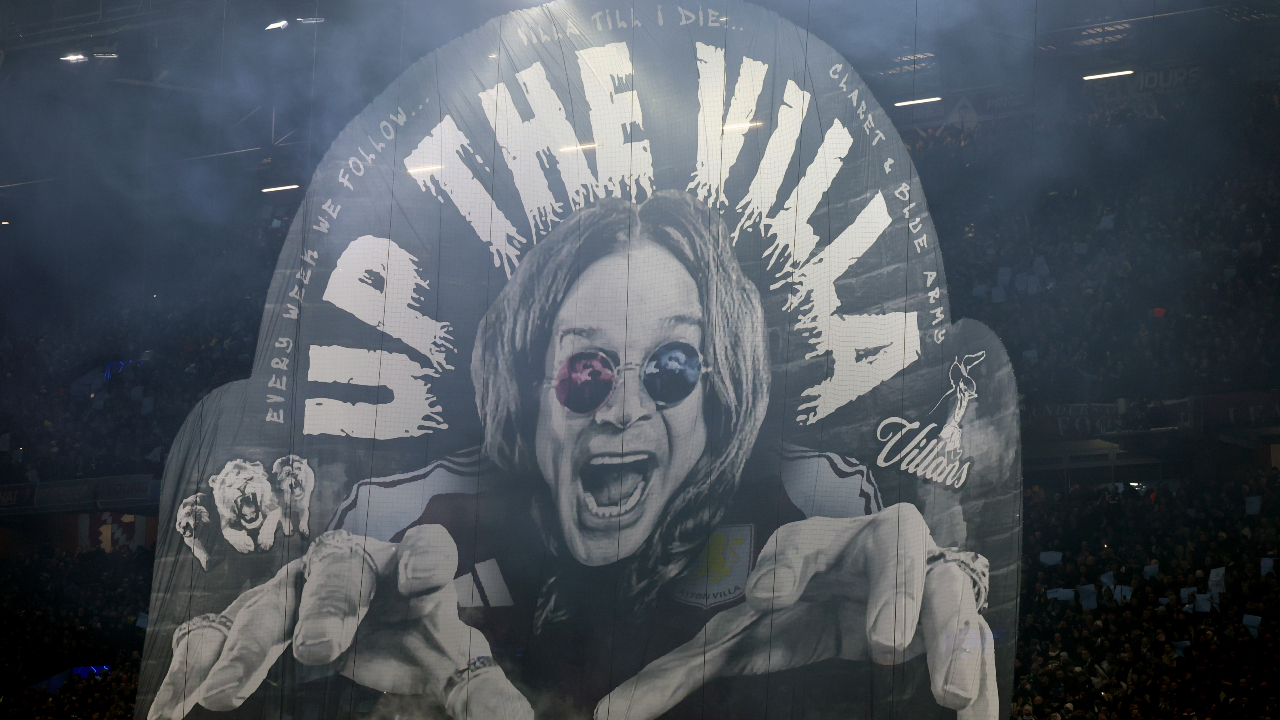

James took control of his life when he confronted his demons in the early 70s. “I played two significant concerts. One was in the Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel in 1971 when I snuck into New York to collect some gold records. Then there was the Paramount concert on the night Tommy Eboli was gunned down. That was when I decided to quit. I had a final meeting with Morris that turned into a humungous blow up.

"For once I stood my ground. I didn’t know whether I was going to leave his office alive, but I was so high on uppers I didn’t really care. We flung each other against the wall and I told Morris – go fuck yourself, for the last time.” Gradually James recovered his self-esteem. “I left Roulette in 1975. I was still in contact with Morris but I wasn’t giving him hits. Eleven years later he offered me my own record company. ‘Whaddya want, kid? I’ll give it to you.’ I admit, I was tempted. That’s the hold he had.”

Levy’s old ways were going out of fashion. As corporate labels took over, independents like Roulette became marginalised. Meanwhile the FBI had Morris’s number. “Roulette were serial tax evaders. The Feds and the IRS were on his tail. They were keeping at least seven sets of books. They picked whichever one suited them best. Eventually the Feds busted him. Morris had a needlepoint sign in his office, which said: O Lord. Give Me A Bastard With Talent. In the ‘O’ of Lord the Feds had planted a camera and a microphone. They were recording everything he said and did.”

Just like the Mob’s, Tommy James’s career has long arms. His songs have been covered to effect by contemporary acts (see box) and there's been talk about his autobiography becoming a Broadway musical and a movie. “I want Chazz Palminteri to play Morris.”

Martin Scorsese’s former wife Barbara De Fina (Casino, Goodfellas, Hugo) is set to produce. The directorial choice is obvious. James wants Val Kilmer to portray him, though Jared Leto would be better as the younger man. Tommy James won’t be forgotten. He invented the modulating rhythm guitar sound on Crimson And Clover, and he had a style, responsible for the arch Kasenetz & Katz bubblegum factory, which spawned glam and punk.

“I view pop as art versus business,” says James. “Initially you’re trying to sell records to 12-year-olds, so don’t get too profound. Morris taught me – you’re not just writing songs you’re making records. It’s a three-minute formula. I’m a pop junkie. I like those rules. I love music that moves people en masse and gets ’em on the floor. My Greatest Hits – The Best Of…. album sold ten million units in 1969.

"For one year I was bigger than The Beatles. A lot of that was down to Morris. Sure, he was as cheap as they come, and yeah, our album covers were cheesy, but the man knew how to sell records. It was the best and worst of times. But you know what? I wouldn’t change them.”

The weekly Gettin' Together with Tommy James radio show is on Sirius XM.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.