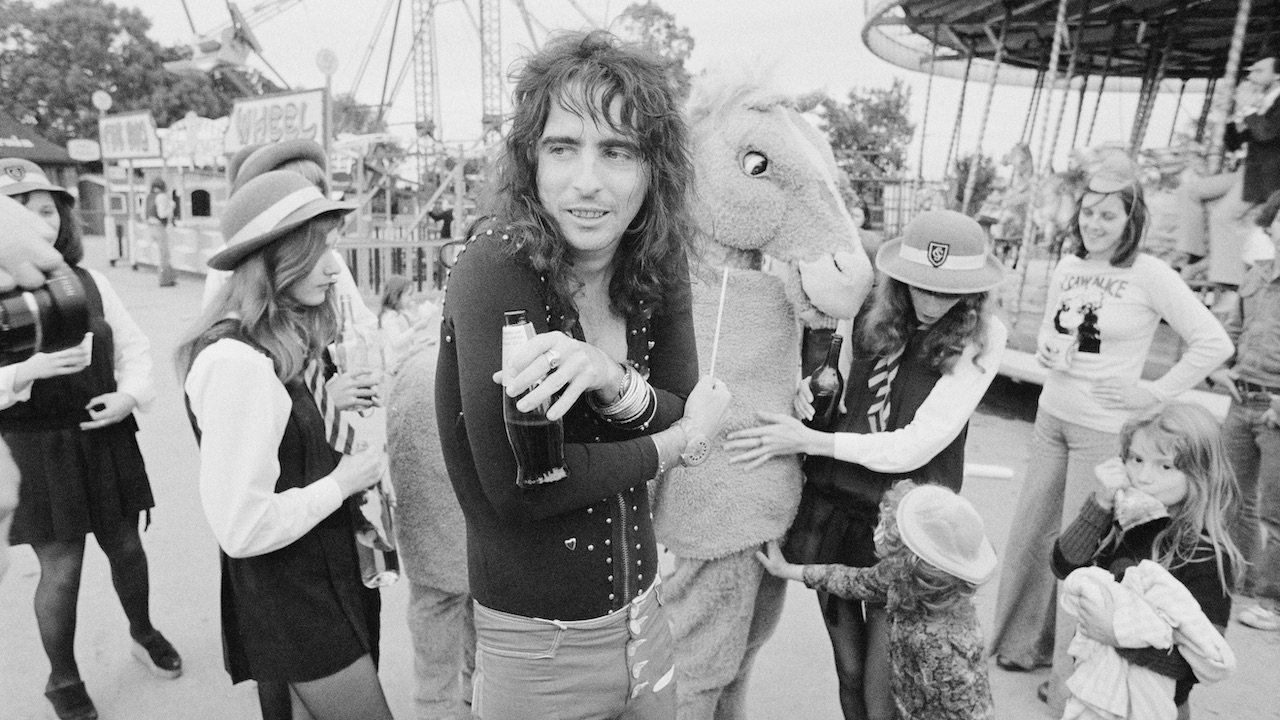

By 1972, the wild rumours surrounding new shock rock superstar Alice Cooper were even freaking out Alice Cooper

"If I believed everything I'd heard about myself, then I'd kill myself" Alice Cooper told a journalist in summer 1972

In the early 1960s an art teacher called Mary Whitehouse decided to reinvent herself as Britain's moral conscience. Horrified and repulsed by what she saw as the creeping erosion of Great British White Christian Values by rogue elements pushing for a dangerous, God-less, ‘permissive society’, first she came for the gays, then the BBC's "filth", then... well, almost everything else, as by the early '70s pretty much all art, culture and media racier than Songs Of Praise seemed to trigger her highly-sensitive outrage meter. Doctor Who was teaching children how to make explosives! Play For Today showed a buttock! A black man is on the wireless singing about his 'Ding-A-Ling'! The country is going to Hell.

In 1972, Whitehouse set her gaze upon a new moral scourge, a demon in human form from The Land Of The Free: its name was Alice Cooper.

Rumours about Cooper, the fallen son of an evangelist preacher, were legion. Once considered a joke, the artist formerly known as Vincent Furnier had started to attract an ever-growing army of impressionable youths to his sick, grotesque stage shows, and when she learned that this... freak... was coming to Britain, Mrs Whitehouse feared that the pure, sin-free souls of the nation's god-fearing youth were in peril. A new single, School's Out, already a hit in America, was basically Satan in black vinyl form, she decided, and enough was enough. The BBC must ban this filth, she thundered.

A Whitehouse ally, Labour MP Leo Abse, went further still, imploring the British Home Secretary to ban Cooper from the UK and spare the country his "culture of the concentration camp."

"His incitement to infanticide and his commercial exploitation of masochism is evidently an attempt to teach our children to find their destiny in hate, not in love," the Member of Parliament argued.

The nation learned that Cooper's live performances involved blood, and violence, and sexual deviancy, and whips, and snakes, and beheadings and... all sorts. It was said that he once bit the head off a live chicken in a ritualistic frenzy. Others claimed that he was pulping live kittens onstage with a sledgehammer. Which, to be fair, even the most liberal deviants would probably consider A Bit Much. Even, it transpired, Mr Cooper himself.

"Whoever thought that one up must be sicker than me," a horrified Cooper told an interviewer from Melody Maker when that rumour was put to him in the summer of 1972. He then took a moment to compose himself. "Besides, I'd use road drills..."

"So many people see evil in us," Cooper added, more seriously. "But if I believed everything I'd heard about myself, then I'd kill myself.

"We seem to be a vehicle for people's exaggeration and fantasy. They'll say they saw us doing things on stage which we didn't do at all. This biting the head off a chicken bit. Christ, I've never bitten the head off a chicken... Maybe a leg or two. [Smiles] But not a head."

The man from Melody Maker seemed entirely disarmed and charmed by the young American entertainer in front of him. But, in the spirit of full disclosure, Cooper did point out that on stage, he was an altogether different person, no longer a civilised Doctor Henry Jekyll, but an unhinged Mister Edward Hyde.

"Everyone would like to release their Mr Hyde at some time," the singer argued. "I release things for people. I act out their fantasies, and it's a great release for me too. You see, I don't have to answer to anybody up there on stage; anything goes, and anything is legal. But we do not condone violence in people. If they can see us up on stage doing violent things - doing things for THEM - then they won't go out and do it in the streets.

"There's got to be more theatre," Cooper insisted. "It's got to happen; it's all been too still for too long... I see something more than most people see in rock. I see something artistic, and - although I hate to say it - cultural about what we're doing."

One month later, in August 1972, School's Out hit the top of the UK's best-selling singles chart, where it would remain for two further weeks. Ever the gentleman, despite what his critics believed, amid the celebrations, Alice Cooper took the time to send a bouquet of flowers to Mary Whitehouse, thanking her most sincerely for making him a household name in Great Britain, and admitting that he very probably couldn't have done this without her help.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.