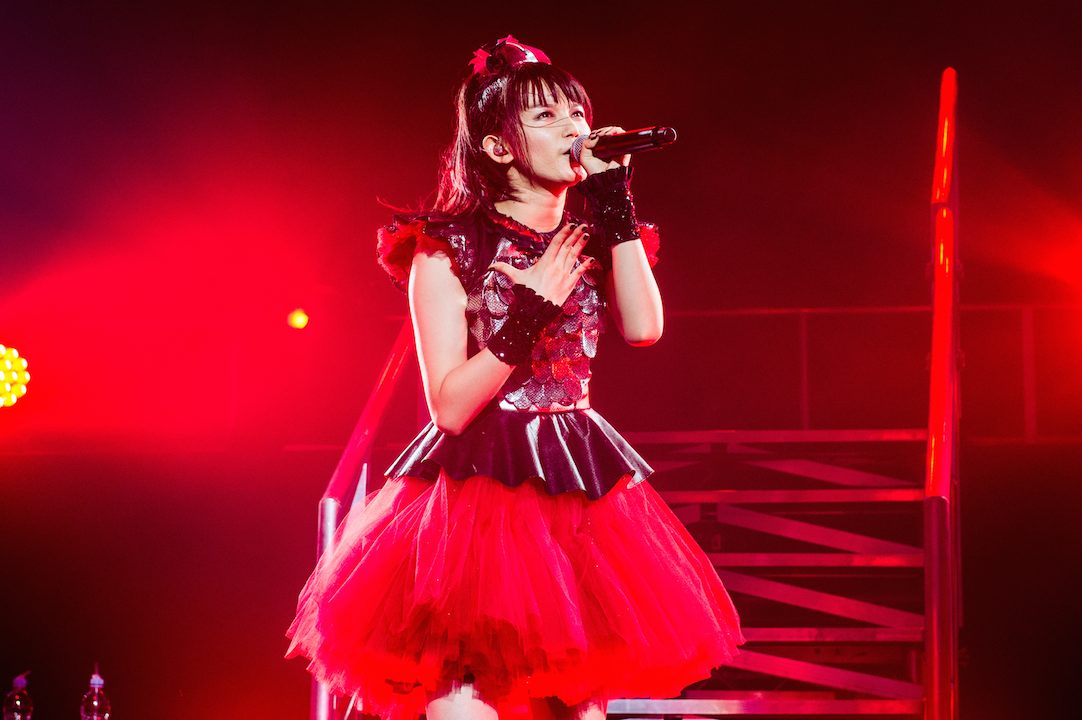

Babymetal: Will The Future Of Rock Look Like This?

Japanese pop-metal trio Babymetal are the name on everyone’s lips. But are they a genuine phenomenon, novelty act or cynical cash-grab?

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Autumn approaches, and so we bid farewell to the Summer of Babymetal, the most exhilarating and divisive phenomenon to hit rock in the last decade.

Barely 18 months ago the Japanese pop-metal cheerleaders had never played in Britain and did not even have a European record label. Today, a group which many dismissed last year as a short-lived novelty gimmick now seem unstoppable, having shared a stage with Dragonforce at Download and opened for Metallica at Reading.

Despite their stellar rise, Babymetal still provoke fierce disagreement across the rock nation. For some purists, Tokyo’s manufactured rock idols are pint-sized Godzillas trampling all over the true spirit of metal. But as their carefully orchestrated plans for world domination come to fruition, Babymetal may yet prove to be the future of rock, with a wave of copycat bands following in their footsteps.

Branding their maximalist fusion sound “kawaii metal” (‘kawaii’ meaning ‘cute’ in Japanese), the trio blend the breathless bubblegum teen-pop vocals of three girl singers with an incongruously heavy guitar-shredding backdrop. The whole concept comes packaged with a goofy back story about a fox god with supernatural powers, plus strikingly cinematic videos with huge viral appeal, notably Gimme Chocolate, which has topped 25 million views online.

Babymetal may look alien to Western eyes, but they did not happen in a vacuum. The three singers (Suzuka ‘Su-Metal’ Nakamoto, 17, and Moa ‘Moametal’ Kikuchi and Yui ‘Yuimetal’ Mizuno, both 16) first worked together in the schoolgirl band Sakura Gakuin, part of Japan’s huge ‘idol’ scene of production-line J-Pop stars. As the idol market has become oversaturated in recent years, managers and labels have looked for ways to refresh the formula, borrowing sounds and styles from more credible subcultures on the rock and metal margins.

Thus Babymetal was born, with their manager and musical svengali Key ‘Kobametal’ Kobayashien listing a team of songwriters including Nobuki Narasaki, a veteran of cult noise-rockers Coaltar of the Deepers, and Takeshi Ueada, formerly of electro-punks Mad Capsule Markets. He also approached power metal band Dragonforce, who collaborated on the track Road To Resistance. Dragonforce guitarist Herman Li says Kobayashi’s dedication to metal is crucial to Babymetal’s underrated credibility.

“He is a really passionate rock metal guy, he really knows his stuff,” insists Li. “People always talk about the girls dancing and the weird Japanese stuff, which is weird if you are not used to Japanese culture. But the music is just a really catchy mix of power metal, rock, even death metal.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

While Babymetal’s look has been labelled ‘punk Lolita’, the trio are less overtly sexualised than many of their J-Pop contemporaries. Gothic and militaristic, their look blends black-and-red body armour with vaguely sinister cheerleader uniforms. This image also borrows from Japan’s ‘Visual Kei’ scene of the 80s and 90s, a glam metal sub-genre with horror-movie trimmings.

Going where no Japanese band have gone before, Babymetal are now a genuine crossover hit in the West, topping the iTunes metal charts around the world last year with their self-titled debut album, despite the commercial handicap of singing in their native tongue. The band made their British live debut in front of 65,000 people at Sonisphere in 2014. There was some derisive laughter, but more cheering than jeering, partly because the musicians backing the singers made a ferocious racket. Two rammed London shows followed, upgraded from small clubs to large concert halls. For all their brazen commercialism, Babymetal’s managers were caught off guard by the sheer scale of the band’s appeal in the UK.

Of course, this success is a triumph of marketing as much as music. The critic for the Japan Times, British-born Ian Martin, claims it is partly down to smartly exploiting Orientalist cultural stereotypes, notably “the gullibility of the Western media in its unquestioning acceptance and regurgitation of any wacky/weird Japan story”.

In a Japan Times column last year, Martin unpacked the sharp commercial logic behind the band’s heavily stylised image. “It’s the work of people who know exactly what they are doing,” he wrote. “In that sense, is it really any more absurd than the theatrics that Western metal acts such as Dragonforce and Manowar have been delighting and dismaying fans with for decades?”

But while critics find Babymetal fascinating, they remain divisive among metal fans. Purists dismiss the band as “manufactured nonsense”, “piss poor” and worse. One review of their debut concluded it “just doesn’t do its job well at being a metal album, nor is it a good J-Pop album… I hope it’s a gimmick that doesn’t overstay its welcome.”

Herman Li is surprisingly laid back about the Babymetal haters. “They have a point, because everyone looks at music differently,” he says. “But they have forgotten that metal has evolved. Bands don’t sound like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath now. It separates the crowd. That’s why people talk about this stuff. People love to hate certain things.”

Koyabashi goes a step further, embracing the Baby bashers as part of his plan for world domination. “Actually it’s good!” he told Metal Hammer last year. “It was the same for Slipknot. A lot of people said they were shit when they started. You always have the haters and it’s all part of what you need to get to the next level.”

For Babymetal, that next level will most likely come with a solid second album that proves they are more than just a novelty act. But they are already a cultural phenomenon, inspiring a wave of young female pop bands across Asia to adopt a heavier sound and look, including Idol group Band-Maid, or South Korea’s Pritz, or Momoiro Clover Z. There are even Babymetal tribute acts and parody bands out there, notably the bearded Ladybaby.

So could blatantly manufactured, image-driven, metal-idol bands like Babymetal be the future of heavy rock? Many serious fans would consider that a nightmare scenario. But Herman Li is not too alarmed by the prospect.

“The image really doesn’t mean very much,” he says. “It’s great to have a good package, but if the majority of people listen because they love the music first, then that’s the most important thing. Babymetal are very important right now. We always need something different that’s going to turn heads, and Babymetal bring people in who have never heard metal before.”

Stephen Dalton has been writing about all things rock for more than 30 years, starting in the late Eighties at the New Musical Express (RIP) when it was still an annoyingly pompous analogue weekly paper printed on dead trees and sold in actual physical shops. For the last decade or so he has been a regular contributor to Classic Rock magazine. He has also written about music and film for Uncut, Vox, Prog, The Quietus, Electronic Sound, Rolling Stone, The Times, The London Evening Standard, Wallpaper, The Film Verdict, Sight and Sound, The Hollywood Reporter and others, including some even more disreputable publications.