“David Byron refused to be helped. On one occasion he slapped me round the face, kicked and screamed at me. We couldn’t take it any more”: The stellar rise and chaotic fall of Uriah Heep, the 70s rock giants who tore themselves apart

Uriah Heep could have been been as big as Sabbath or Zeppelin if it wasn’t for drink, drugs and egos

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Peers of Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, Uriah Heep were part of the first wave of British hard rock bands – and for a moment it looked like they could become as successful as those bands. But drugs, alcoholism and in-fighting meant they failed to deliveron their initial promise. In 2012, Classic Rock looked back on the rise and fall of a band who were never as big as they could have been.

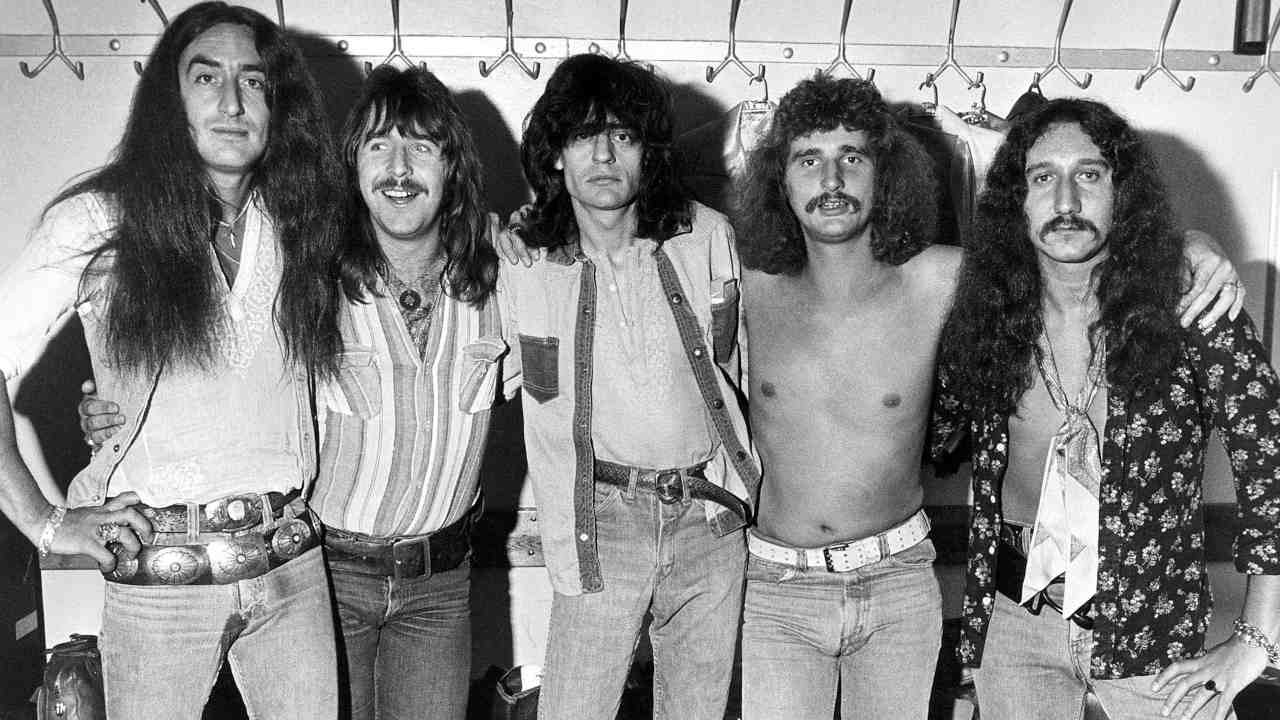

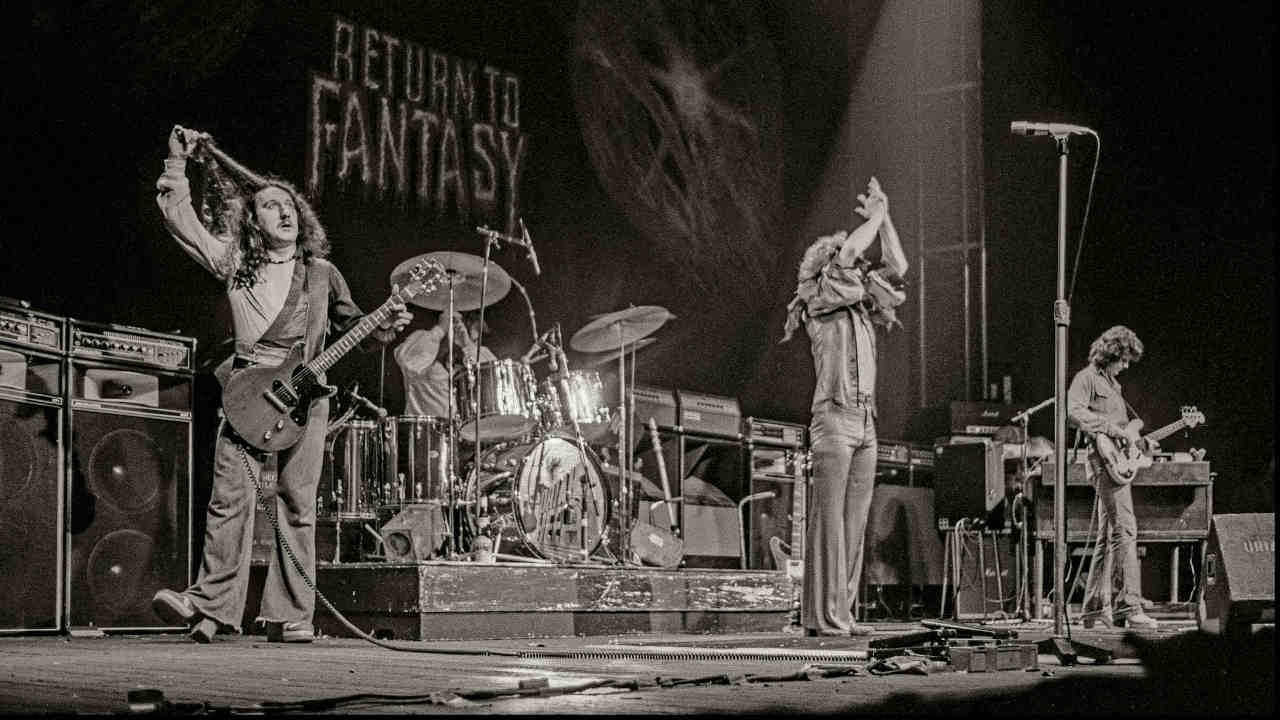

August 14, 1975, and Uriah Heep are about to take the stage at Philadelphia’s Spectrum arena. The British band have the wind behind them thanks to the transatlantic success of their eighth album, Return To Fantasy, and 25,000 people have crammed into the sold-out venue to see them play tonight.

For the past six years Heep have grafted hard to become one of the biggest rock bands around. Their bombastic, multi-layered mix of hard rock and prog has turned them into a true people’s band: loved by record buyers and concert-goers, hated by critics. Return To Fantasy, artistically an improvement on its pedestrian predecessor Wonderworld, has given them their first UK Top 10 album.

To outsiders, Uriah Heep are at the top of their game. The reality, however, is that the five-piece are patching over a series of enormous cracks. Behind the scenes, toxic personality clashes are tearing the band apart – a situation not helped by alcohol and drug problems. Bassist Gary Thain had been fired at the start of the year due to a debilitating heroin addiction; within months he would die of drug-induced respiratory failure. His replacement is John Wetton, formerly of Family and King Crimson.

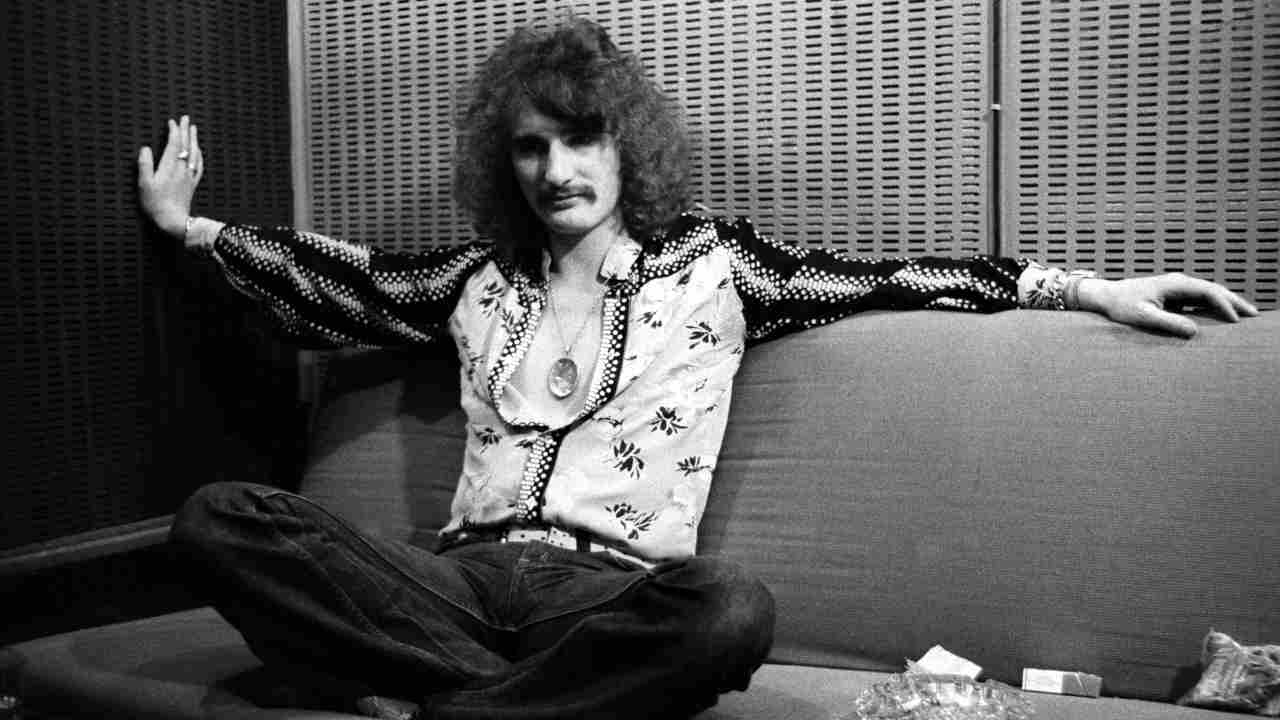

Right now the band have an even bigger problem: David Bryon. Their charismatic singer is in the grip of alcoholism, which is affecting his performances on stage and his life off stage. And, here in Philadelphia, matters are about to reach a head.

Bryon has spent the afternoon knocking back his favourite Chivas Regal whisky; by showtime he’s a mess. Such is his inebriation that at one point in the show he staggers into a microphone stand, cutting his lip. Realising that he’s bleeding, and mistaking the cheers in the arena for laughter, a mortified Byron turns on the audience, telling the whole damned lot of them to “fuck off”. The announcement astonishes everybody, on stage and off.

Nearly 40 years on, Heep’s usually irrepressible guitarist Mick Box is still embarrassed by the memory. “I was tuning my guitar at the time and couldn’t bring myself to turn around and face the audience,” he says with a sigh.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I was embarrassed for David and for us,” says keyboard player Ken Hensley. “When your lead singer curses out an entire audience what do you do? He was pissing my career down the toilet as well as his own. I made my feelings clear a few shows later by walking out on the tour. Looking back, I should have been more mature instead of simply disappearing. But I was angry and it was a knee-jerk reaction.”

It was down to the band’s manager, Gerry Bron, to pick up the pieces. Bron cut short a holiday in Barbados and flew back to London to sweet-talk Hensley into returning to the tour. For Bryon, however, the writing was on the wall. “In order for Ken to stay in the band, we agreed that David would have to leave,” Bron says today.

Byron was unaware of the axe that hovered above his head at the time, but the increasingly remote attitude of his bandmates in the wake of the Philadelphia debacle only made him feel increasingly persecuted and isolated. Within 12 months Byron was out of the band. He played his final show with Heep on June 25, 1976 in Bilbao, Spain, although not before kicking in the plate glass front door of the venue. “I think even David had resigned himself to being sacked by then,” Box later observed.

But by then it was too late. For Byron, and for Uriah Heep, things would never be quite the same again.

The Uriah Heep story is one of both triumph and tragedy. Between 1972 and 1976 they released six albums that established them as one of the key bands of the era, at least two of which – Demons And Wizards and The Magician’s Birthday – stand as landmarks of 70s rock. But behind the scenes were ego problems, clashes with their manager, and substance problems that result in the premature deaths of two band members.

Heep’s roots lay with Mick Box and David Byron. The down-to-earth guitarist describes the flamboyant lead singer (born David Garrick) as “a proud peacock of a man”. Together they had been members of The Stalkers and then Spice. It was the latter band who were spotted at a gig in High Wycombe by Gerry Bron, the man who soon afterwards would become their manager, producer and, with the foundation of his Bronze Records in 1971, their label boss.

Bron is a central figure in the Uriah Heep story – and a controversial one. Older than his charges, he had already worked with Manfred Mann and Colosseum. Uriah Heep’s success would allow him to expand the Bronze empire and eventually sign the likes of Motörhead, The Damned and Girlschool.

“David Byron was definitely the band’s leader,” Bron recalls of Heep’s early days. “He came into the office and charmed everyone, including the secretaries. Four years later this nice guy had changed into a complete bastard, a demon.”

As Spice prepared to record their debut album, Bron proposed that they change their name to Uriah Heep – inspired not by the character from Charles Dickens’s 1850 novel David Copperfield, but by an advert placed in the Melody Maker by a potential employee who had adopted the moniker. “It was in the Situations Wanted section: ‘Experienced roadie seeks work, please call Uriah Heep…’,” Bron recalls. “I thought, ‘Bloody hell, what a fantastic name.’”

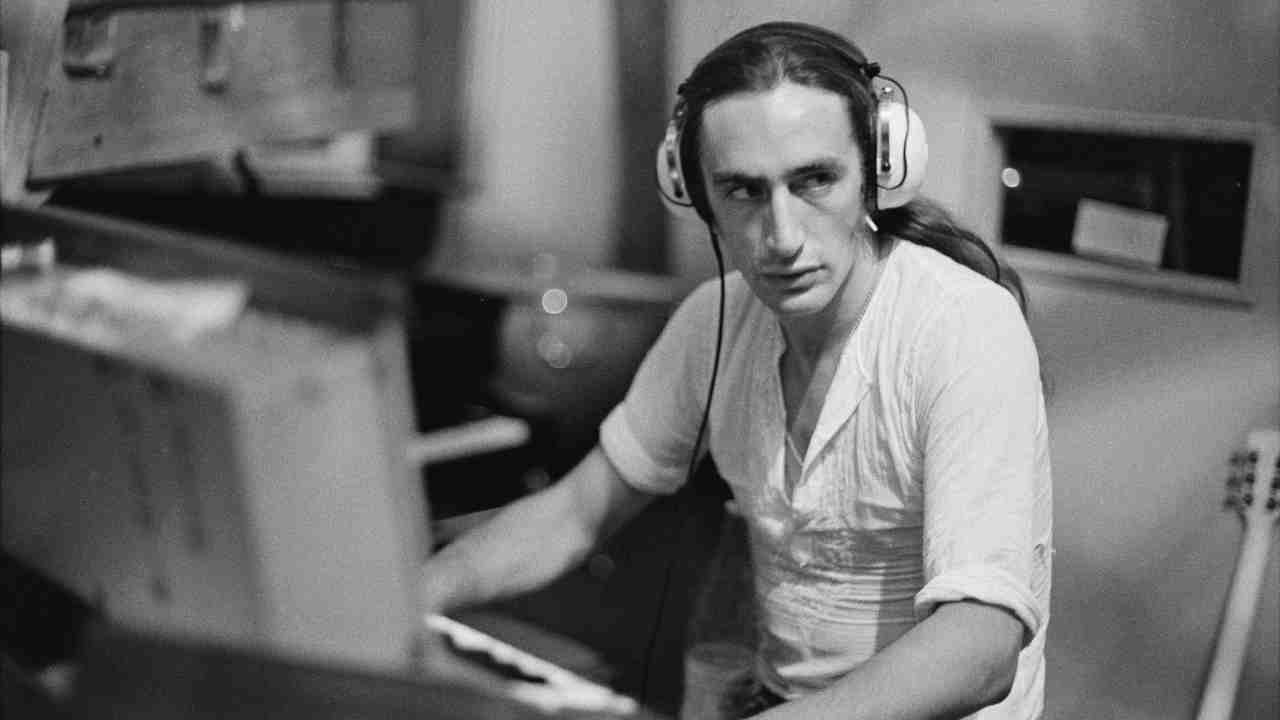

Equally pivotal in the Heep story was the addition, around the same time, of keyboard player/second guitarist Ken Hensley, a man who would prove to be crucial to Heep’s long-term future. The Londoner had previously been a member of blues/prog outfit Toe Fat and was looking for a better platform for his considerable talents. Hensley’s rich Hammond organ embellishments were the perfect foil for Byron’s flamboyant falsetto and the wah-wah-driven guitar attack of Box, all of which was sweetened by multi-part vocal harmonies. More pertinently, Hensley formed an alliance with Gerry Bron that quickly became as important as the Box-Byron coalition. “Ken and I were a great team,” Bron says. “I didn’t get on that well with the rest of the band.”

Despite being mauled by the press (“If this band makes it, I’ll have to commit suicide,” said one writer in Rolling Stone magazine), Uriah Heep’s 1970 debut album, Very ’Eavy… Very ’Umble, produced by Bron, was a minor success. But it would take them another two albums – Salisbury and Look At Yourself, both released in 1971 and both again produced by Bron – for Heep to establish a solid musical direction.

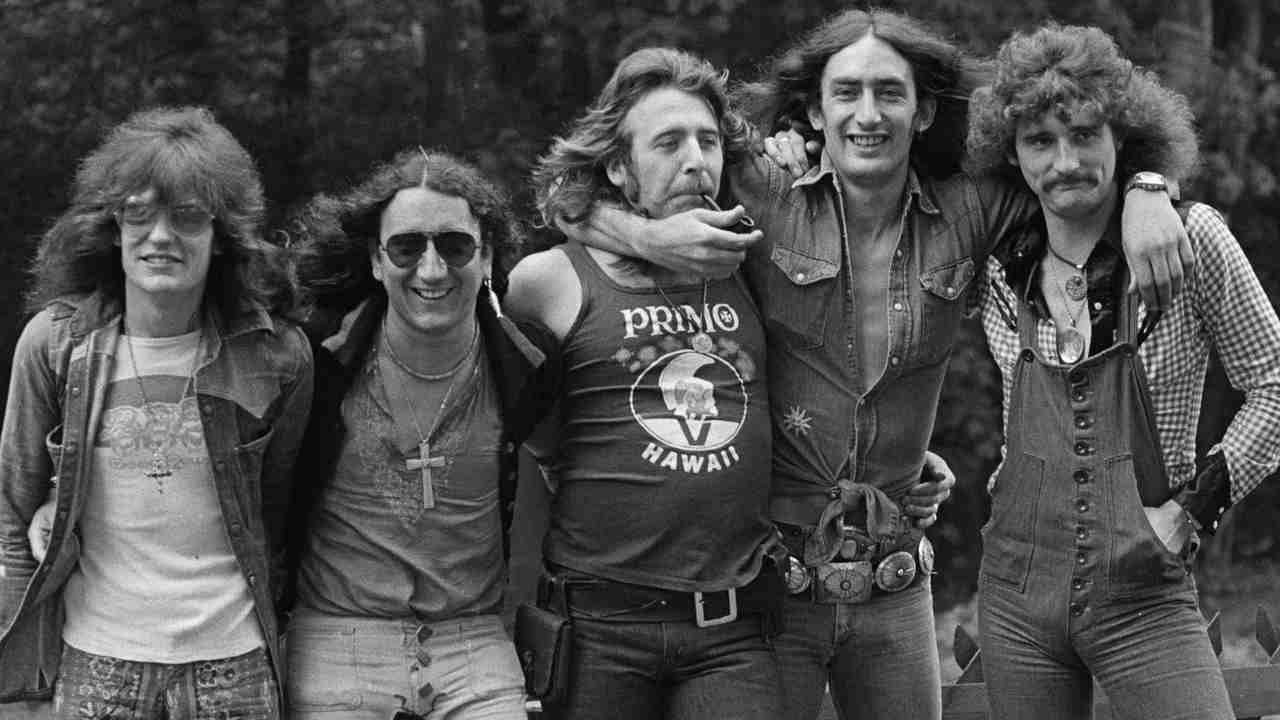

Everything came together with 1972’s Demons And Wizards. Housed in an eye-catching, Roger Dean-illustrated gatefold sleeve, it is still considered to be the band’s crowning glory. Gloriously baroque songs such as Easy Livin’ and The Wizard captured Uriah Heep’s creativity – the latter even includes the multi-tracked sound of a whistling kettle that had accidentally gone off during a playback.

A significant part of the record’s artistic success was the presence of a new rhythm section: New Zealand-born bassist Gary Thain added some elegantly melodic bass lines, while drummer Lee Kerslake had an aggressive approach that previously had been lacking. Crucially, both were also useful singers, adding extra depth to the band’s distinctive multi-layered vocal harmonies. Personality-wise, though, they were like chalk and cheese: Kerslake was outspoken and ambitious, while Thain was shy and retiring.

“With Gary and Lee there was such an incredible chemistry,” says Hensley. “The lines of communication were open and, with none of the obstructions that came later, the chemistry created by those five people was magical. The egos were there, they just weren’t clashing. Substance abuse was also present but it was minimal.”

Ashley Howe, Gerry Bron’s trusted engineer, had first encountered Uriah Heep in 1969 when he was a 16-year-old working in a studio as a tea boy-cum-tape-operator. He eventually rose through the ranks to take charge of Heep’s High And Mighty sessions, before going on to produce their Abominog and Head First albums during the band’s 80s renaissance.

“Heep were easy to work with because the talent flowed out of them,” he says. “That didn’t dwindle with time, but as personality conflicts grew it become harder to draw out.”

Ken Hensley is unflinchingly honest when it comes to his working relationships with his bandmates. “Creatively speaking, Mick was the least influential person in the band,” he says. “However, he was a very important part because his style and technique were unique. Lee was the perfect drummer for Heep, but he had a desire to exert a creative influence that sometimes became bit over-the-top. The back-up to fulfil that passion wasn’t there, but in the same way as Mick’s contribution was valuable, so was Lee’s. David Byron was the quintessential showman, on stage 24 hours a day. His interpretation of my lyrics was exemplary – even now I cannot bring them to life the way he did.”

Byron indeed possessed an outstanding voice and a magnetic stage persona. But there was a darker side to his character.

“As a frontman, David blew anybody off stage – he could even eat Rod Stewart alive,” Lee Kerslake says today. “The problem was that he didn’t have an ‘off’ switch. There was also some shyness, but he disguised it with his outgoing behaviour.”

Released in May 1972, Demons And Wizards gave Heep a UK Top 20 album – and opened up a way in to the lucrative US market. Not wanting to let the momentum stall, they decided to put out a follow-up, The Magician’s Birthday, six months later. Or, rather, Gerry Bron did.

“The songs just weren’t ready,” says Ken Hensley. “They wanted to milk the cow as much as they could.”

Despite Hensley’s reservations, The Magician’s Birthday remains one of Heep’s cornerstone albums. It includes such landmark songs as Sweet Lorraine, the majestic Sunrise and the epic 10-minute title track.

As well as recording the The Magician’s Birthday they also toured Britain and North America during the same period. But clear factions were starting to form, with Hensley and Bron on one side, and Box, Kerslake and Byron on the other. Meanwhile, Gary Thain was becoming an increasingly isolated figure.

“Gary’s contribution was greater than is recognised,” Bron offers. “Because he didn’t write songs, he came to believe that his talent was less important than the others. I used to have long chats with him, and he would say: ‘Gerry, I haven’t got anything [to offer].’ But his gift to the band was his incredible bass playing. However, at the same time he was getting more and more into drugs.”

Thain was becoming addicted to heroin, a problem he initially managed to keep secret from the rest of the band. The bassist was the only member of Uriah Heep on smack, but some of the others were finding they had their own problems with booze and cocaine.

“There were a lot of drugs and drink, and that made it harder to be creative,” says Box. “I like a good drink myself, so I was caught in the middle of it all.”

“You must understand how much being strung out on coke changed me,” admits Hensley. “I became a monster to work with. Becoming addicted during

our first US tour was the greatest mistake of my life.”

The growing tensions weren’t helped by the fact that Hensley was starting to dominate the songwriting. Five of the eight songs on The Magician’s Birthday were written exclusively by the keyboard player; the remaining three were co-written by Hensley and the others, including the good-versus-evil title track, which featured a symbolic battle between guitars and drums concocted one night after returning to the studio from the pub.

“Kenny was an absolute genius as a writer,” says Kerslake. “I’d hate anyone to think otherwise. But when he brought in a song the rest of the band tore

it apart, put it back together and made it what it was. He couldn’t have done it without the knowledge and talent of each member of the band.”

Inevitably, Hensley and Bron disagree. “I’ve heard that argument so many times before,” says Bron. “Look, Ken was the captain, and the band the team. But they only ended up resenting him.”

“Had I been in that situation, where one guy writes one hit after another, I certainly wouldn’t have challenged him,” adds Hensley, “I’d have washed his car and made him tea. I’d want him to keep doing it.”

Mick Box is adamant that Hensley’s work rate changed the band dynamic. “Once we had success with some of Ken’s songs, nobody else got a look in,” he says. “Being suppressed causes a lot of tension.”

Hensley’s relationship with the rest of the band was further strained as the royalties began to flow in. As chief songwriter, he earned significantly more than the others – and he wasn’t embarrassed to flaunt it.

“If I had a new car, I’d show it off,” he says. “But I challenge anybody to deal with having nothing then becoming a millionaire overnight. My behaviour then is another thing that I’d go back and change. But of course that’s impossible.”

Hensley wasn’t the only one causing resentment within the Heep camp. Lee Kerslake claims that Gerry Bron’s ego had become “bigger than the rest of us put together”. The drummer recalls an incident at a gig in Rome when Bron was overheard talking to the show’s booking agent. “I am Uriah Heep, and what I say goes,” their manager allegedly said.

“It’s perfectly true,” Bron says today. “I named the band, I put the whole thing together, and they’d never have made it without me steering them. So that’s not an unreasonable claim.”

Amid the growing problems, engineer Ashley Howe tried to lighten the mood. “Gerry routinely fired me during each project, for doing stupid things like winching a cardboard box disguised as a 10-ton weight into the air and dropping it onto Ken Hensley’s head as he was recording. Or putting together something made of candles and an alarm clock to resemble a bomb and hiding it in Ken’s piano – until Lee Kerslake heard it ticking and threw it through the window. But, as a thank you, once the album was completed he’d pay to send me to wherever I wanted to go on vacation, and re-hire me for the next one.”

Having recorded their first four albums at Lansdowne Studios in West London, the band decided to record their next two overseas. All now agree that it was a grave error. An increasingly unhinged David Byron ran riot during the recording of 1973’s Sweet Freedom at Chateau D’Hérouville near Paris, while Wonderworld – put together during three months of hedonism and bickering at Musicland in Munich – found both Thain and Byron’s problems worsening.

“I’ll never forget watching David trying to cross a dual carriageway that separated the hotel and the studio in Munich,” says Box, wincing. “Cars were whizzing past him, and I thought: ‘He’s going to die.’ But he made it without spilling a drop of the champagne cocktails he was carrying in each hand.”

The band did try to talk to the singer about his problems, but they were hardly clean-living themselves. “Demanding that he stop would have been hypocritical,” says Lee Kerslake. “Besides which, he’d just go off and sulk. Deep inside I think he knew he was self-destructing, he just couldn’t stop.”

The magnitude of Byron’s problem became apparent during the Wonderworld sessions. “David broke the unwritten rule by singing half-cut with a bottle of Dom Pérignon,” the drummer recalls. “Until then nobody drank while we were tracking.”

“I still recall being in Munich where something seemed to be distracting Ken in the studio,” says Bron. “David was crawling along the floor, trying to reach his bottle of whisky in the overdub booth.”

Miscommunication and discontent were such that Box and Kerslake went into the studio one day during the sessions and found that Bron and Hensley had flown back to London. “We hadn’t finished the album but they’d had enough,” fumes Kerslake. “How dare they leave us there without warning?”

While certain members of Uriah Heep are quick to paint Bron as the villain of the piece, Ashley Howe defends him: “They were a bunch of 25-year-olds that loved their rock ’n’roll, but Gerry knew how to run a business. There he was, wearing a three-piece suit, trying to control these semi-lunatics. He was the best manager the band could have had.”

Box, Kerlsake and Hensley all say now that not only was Bron wearing too many different hats when it came to the band – he now represented them for management, recording, touring, publishing and merchandising – but his day-to-day commitments

to Bronze Records and the acquisition of an airline, Executive Express, meant he was taking his eye off the ball. Bron himself agrees. “Yes, I wasn’t paying enough attention, but that was because they weren’t doing their job,” he says. “I probably had lost interest by the time of Wonderworld because, frankly, they were no longer very good.”

By 1974, with an entourage of 20 people accompanying them on the road in America, Uriah Heep had become a moneymaking machine. “However, they were not doing so well that they could just stop – for whatever reason,” says Bron.

It was on the tour in support of Wonderworld that Gary Thain’s health began to be a real problem. The unremitting schedule was taking its toll on the heroin-addicted bassist. Stories abound of Thain being carried onto flights on luggage trolleys, or his bandmates having to convince pilots to let him on the plane when he was in no fit condition to travel.

“If Gerry was half the manager that he bragged of being, the band should have come off the road and those that needed treatment been sent to rehab,” maintains Kerslake. “But instead he was so busy with his studio, his record label and his airline that he didn’t consider his real bread-earners.”

Bron responds to the accusations with customary calmness. “Listen,” he says, “it’s easy to say these things now but nobody complained at the time. They continued to do what they were doing without any fuss.”

Mick Box vehemently disagrees. “Making such an important decision on behalf of the band is what management is about, surely?” he fumes.

On the road, the madness continued. Following a show in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, an intoxicated Byron keeled over in his hotel room. Blood gushed from a deep head wound as he lay comatose on the bathroom floor. Had the singer not given his room key to a female fan, he would more than likely have bled to death. According to Bron, when Byron arrived at the hospital the singer couldn’t recall his name, date of birth or where he lived.

“Even when confronted, David was unrepentant,” says Hensley. “He showed no signs of wanting to change. Clearly, the situation couldn’t continue.”

One of the road crew’s jobs on the US tour was to give a nightly debrief of each show, phoned in to the Bronze office in London and left on an answering machine. “Usually it was: ‘All is well, here are the figures…’ and ‘We’re on the plane to the next gig,’” says Gerry Bron. “But Byron, who by then was very drunk and taking pills, found out and started leaving his own messages: ‘You load of fucking wankers’. He knew the girls in the office would have to transcribe his filth.”

Bass player Gary Thain left Uriah Heep in January 1975, after the Wonderworld tour ended. Eleven months later, on December 8, his girlfriend found him dead in the bath in his flat in Norwood Green, south London, having died of respiratory failure from a heroin overdose. He was just 27.

The news prompted Ken Hensley to go on a cocaine binge. Mick Box doesn’t remember where he was when he learned of Thain’s death, but he says “it would have been on tour somewhere. How did it make me feel? Put it this way: I wasn’t surprised.”

With bassist John Wetton having been brought in to replace Thain, 1975’s Return To Fantasy so successfully corrected the wayward course the band found themselves on after Wonderworld that it became the band’s biggest-selling album to date. Flush with confidence, Heep opted to produce their next album, 1976’s High And Mighty, themselves. Box, who later termed the record “less of the ’eavy and more of the ’umble”, admits he was more interested in going to the pub than actually creating music.

“And that’s what he did, along with Lee,” says Hensley. “John Wetton sometimes showed up when he wasn’t busy with Bryan Ferry, which was nice of him.”

After three albums away from their orbit, during which time Bron installed him as studio manager of the Roundhouse Studios in North London, Ashley Howe re-entered the inner circle to engineer High And Mighty. With supreme understatement, he uses the word ‘difficult’ to describe those sessions.

“Certain people became a bit hard to control, which worsened after a few jars,” he remembers. “Band members became obstreperous. One guy felt it necessary to remind me that I’d begun as the tea boy. I won’t name him, but it wasn’t Mickey.”

Box recalls Byron being sent to the studio’s basement, where a microphone had been set up to capture the unusual acoustics. “Only we recorded the part, and because drugs and drunk were being used, poor old David was forgotten about. An hour later somebody pushed up a fader and we heard: ‘You bunch of cunts. Let

me out of here!’”

Howe admits to feeling uncomfortable when Bron attended the final playback of High And Mighty. “Gerry said that he liked what we had done, but I suspect it was very emotional for him to no longer be involved. It must have been a bit like letting a child go.”

In fact Bron hated High And Mighty. “Gerry was never going to like it under any circumstances because his nose was out of joint,” says Hensley. “Kicking him out as producer was the wrong decision. We were trying to blame him for everything that was going wrong.”

“As instrumental as Gerry was in the building up of Uriah Heep, he was equally guilty in bringing it down,” Box has said.

“That’s them trying to find excuses for having dropped the ball,” responds Bron now. “I don’t blame them for that. The real reason for Uriah Heep’s downfall is the friction between them, especially David’s jealousy of Ken. It was childish.”

As much as the prospect terrified them, the band realised that David Byron had to go. The singer was sacked at the end of the band’s Spanish tour in June 1976. A statement issued by Bron shortly afterwards explained that the decision had been made “in the best interests of the group”, and revealing that they had “already secured a replacement singer”.

Byron informed the NME that he was “absolutely relieved” by the move, adding: “All the things that have been tearing me apart have gone.” Referring to Hensley’s domination of the writing process, he went on to tell a Dutch magazine: “We should have used everyone’s songwriting. That’s why High And Mighty is a bummer to me.”

Box, Kerslake, Hensley and Wetton all appeared on Bryon’s debut solo album Take No Prisoners (recorded before his dismissal), but the singer’s problems prevented him from carrying on alone.

“David refused to be helped,” says Kerslake. “On one occasion he slapped me round the face, kicked and screamed at me. We couldn’t take it any more. The fear was that he would drag us down with him.”

It’s a revealing indication of Heep’s standing that David Coverdale, Paul Rodgers and Ian Hunter all auditioned to replace Byron, even though each turned the gig down. Hunter claimed to have been offered £5,000 a week – no small sum in 1976. “I didn’t really like what they did,” he later said. In the end the band settled on former Lucifer’s Friend frontman John Lawton as Bryon’s replacement.

Subsequent albums Firefly, Innocent Victim and Fallen Angel kept the group’s name alive, especially in Germany, but a rift between Lawton and Hensley gradually opened. Replacing Lawton with Lone Star’s John Sloman for 1980’s ill-fated Conquest was a disastrous move, and prompted Hensley’s departure from the band.

It was all too much for Gerry Bron. “Without Ken, David Byron or Gary Thain, as far as I was concerned we no longer had a band,” he says.

In 1982, Box and then-bassist Trevor Bolder tried to bring Byron back for the Abominog album, but the singer was so far gone that he turned down the idea.

“We went to see David at his house, and afterwards we sat in the car, exhausted,” Box recalls. “I said to Trevor: ‘What just happened there?’ We’d had hope in our hearts [that he would rejoin]. But he was drinking worse than ever, and he ended up trying to convince me to join his band.”

Byron never conquered his demons. On February 28, 1985 he was found dead at his home in Reading. The coroner cited alcohol-related complications as the cause of death.

Gerry Bron admits that he still thinks about the sacking. “But what were we supposed to do?” he says. “Bring everything to a halt and wait for David to sort himself out? How would we know that he’d done so? More importantly, did he even want to stop?”

The departure of Byron ended Uriah Heep’s imperial period, though not their career – they have continued to be a presence on rock’s landscape. Today Mick Box is the sole original member, proudly flying the flag for the band he helped form more than 40 years ago. Between 1986 and 2007 the band – Box, Kerslake, bassist Trevor Bolder, singer Bernie Shaw and keyboard player Phil Lanzon – enjoyed a period of stability that they never experienced during their 70s heyday.

But even then the past occasionally reared its head. In December 2001 Ken Hensley and John Lawton both performed with Heep at London’s Shepherd’s Bush Empire at an event called The Magician’s Birthday. Hensley shudders at the memory.

“It was bloody awful,” he says. “I wasn’t properly prepared, and I didn’t like some of the jokes they made while rehearsing my songs. I looked across the room, and there should’ve been somebody stood where Bernie Shaw was. It felt very fake. But at least I got to make my peace with Lee again.”

“Ken’s comments regarding Bernie are a bit of a cheap shot,” says Box. “As a band we did everything that we could to make Ken welcome, and humour is a good ice breaker. I am sorry he didn’t see it that way.”

Kerslake left the group on health grounds in 2007. “My hospital check-up confirmed eight or nine complaints including tinnitus, and arthritis of the arm, elbow and knee,” he says. “At my age [64] there’s no way I could do another world tour.”

In an unexpected move, Hensley and Kerslake are considering working together again. Besides joining Blackfoot, working with W.A.S.P. and Cinderella and releasing solo material, the keyboard player maintained a low profile until the late 1990s. Today he has a new band, Live Fire, and a solo career; a new album, Love… And Other Mysteries, will be released this spring.

Mick Box has no plans to slow down. During the past two years, Uriah Heep have followed the sort of itinerary that puts younger bands to shame, playing five tours of America, several Russian treks, and gigs in such far-flung places as South Africa, Georgia and Kazakhstan. The band plan to record their 24th album in the spring.

The guitarist says he’s saddened by Bron and Hensley’s perceived bitterness but, magnanimously, thanks each on them for their contributions, even as he pushes ever onwards with Uriah Heep.

“We have a loyal and still-growing fan-base that often thanks us for providing the soundtrack to their lives,” Box concludes. “Our catalogue is played at births, weddings, funerals and milestones in between. Night after night we see hundreds and thousands of fans singing along to our songs, old and new, sometimes with tears of joy. That is fulfilment indeed.”

“I’m very proud that we took a fairly flimsy amount of talent and a lot of determination and created something huge,” Ken Hensley says, somewhat modestly. “With hindsight I realise that the band fell apart for many reasons that were not music-related, which is disappointing.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 171 (April 2012). Ken Hensley, Lee Kerslake, Trevor Bolder, John Wetton, John Lawton and Gerry Bron have passed away since the article was published.

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.