The Last Days Of Pantera

Pantera kept metal’s fire blazing in the 1990s. But as the decade came to a close, they were headed for an almighty flame-out

It was perhaps inevitable that a band who embraced excess and extremity in the way that Pantera did would implode in such acrimoniously bitter and crushingly sad circumstances. Riding high in the Billboard chart and carrying metal almost singlehandedly on their backs after the success of 1994’s Far Beyond Driven, the strain began to take its toll both physically and mentally.

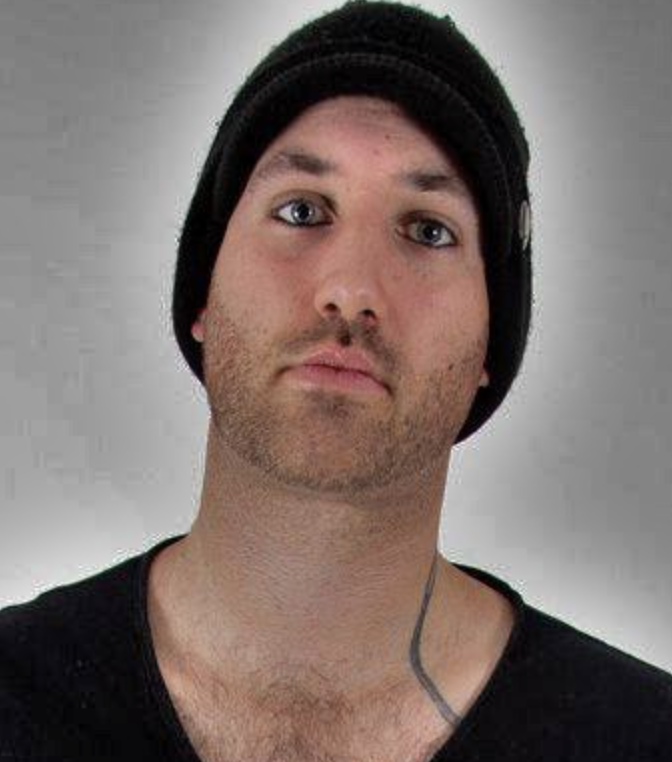

The catalyst could be traced to the back injury that Phil Anselmo suffered in the early 90s, leaving the frontman with three destroyed discs in his lower spine. “I crushed my back for the cause, for the music,” Phil told Hammer in an interview in 2010. “I didn’t know what else to do. I definitely have an addictive personality, but it’s apparent that painkillers and drugs and whatnot are addictive.”

As the Pantera juggernaut steamed ever onward, with Vinnie Paul and Dimebag Darrell ringleaders of the biggest booze-fulled party in metal, Phil began to use anything he could to try and alleviate the pain. Quickly, a divide began to develop, with the Abbott brothers convinced that the band’s success had changed Phil for the worse, while the singer himself became more erratic, ignoring doctors’ orders to have an operation and instead gritting his teeth and fighting through the pain barrier as Pantera continued to tour. Wounded and heavily inebriated, Phil’s mood and performance levels suffered dramatically, creating resentment from which no resolution was ever to be reached. “They were always different than me,” he snarled in what became a notorious interview with Hammer in 2004. “They always had their circle of friends and I had my circle of friends.”

By the time the band came off the road and entered the studio to make 1996’s The Great Southern Trendkill, the fracture had changed Pantera’s dynamic completely. Phil wasn’t present in Dallas during the recording of the album’s music, preferring instead to do his vocals in solitary at Trent Reznor’s Nothing Studios in New Orleans.

“It was a long-distance relationship and pretty different from the other records,” says producer Terry Date, who had worked with the band on every album since 1990’s Cowboys From Hell. “The band would work on the music in the studio and send it out to Phil. I worked with Phil on the vocals in New Orleans. It was kind of a dark time in Phil’s life and so the lyrics and the feel very much reflect that.”

Even so, Terry denies any suggestion that Phil was difficult to work with during recording. “I was kind of aware,” he states when asked about the frontman’s addictive tendencies. “I saw a lot of it away from the studio, but, as far as when we were in the studio together, Phil was always on his game. He’d come in with his lyric sheets every day and he’d underline every lyric that he wanted to double track, and he would be there for two hours getting it done and then leave.”

In 1996, The Great Southern Trendkill, their darkest and heaviest album yet, entered the Billboard charts at a hugely respectable Number Four. With Pantera heading out to play arenas across the US with White Zombie, it seemed to the outside world that this was a band who were very much still stronger than all. Sadly, that wasn’t the case.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In hindsight, it’s hard to fully appreciate the shock that the metal scene felt when news began to emerge on July 13, 1996, that Phil had gone into cardiac arrest due to a heroin overdose, after a show at the Coca-Cola Starplex in Dallas. “I, Philip H. Anselmo,” began the statement he put out in the aftermath, “...injected a lethal dose of heroin into my arm, and died for four to five minutes.” It was the first declaration to the public that all was not well for the Cowboys From Hell.

Post-overdose, it became harder and harder to shake the suspicion that the brotherhood that made Pantera so beloved was crumbling. Two covers – an Anselmo-free version of ZZ Top’s Heard It On The X with Dimebag on vocals under the moniker Tres Diablos, and their take on Ted Nugent’s Cat Scratch Fever – were the sole releases from the band before 2000’s relatively disappointing swansong, Reinventing The Steel.

Devildriver frontman Dez Fafara was living with Phil in New Orleans at the time of Reinventing The Steel’s composition, and vividly remembers the creative tensions that nearly tore the band apart before its release.

“I remember Phil and me walking out by the riverbank where he lived,” says Dez today. “And him telling me he was gonna leave Pantera. I’d hear good conversations and bad. I would see Philip get off the phone really happy because Dime loved his lyrics, and then I’d hear them flip out at each other and him slam down the phone and grab a bottle. I think he felt ganged up on by the brothers. Tensions were running really high.”

When the band did return to the UK for their first full tour in six years, this writer was present at Brixton Academy on April 30, 2000 to witness what turned into a car-crash performance. As Phil staggered around the stage, slurring incoherently for minutes on end between songs, his bandmates stood and seethed in the background. Dimebag in particular was visibly unable to hold in his ire as Pantera managed a paltry 13 songs in a two-hour set. It would be their last-ever UK show.

As Pantera wound down the touring cycle for what would be their final album, Phil began to concentrate on other projects. Both Down and Superjoint Ritual released records in the year 2002, with no sign given by Phil of a return to his ‘day job’.

“People always say Phil ruined Pantera because he did Down and Superjoint,” Dez says. “But he got forced to do those projects because he felt like his creativity wasn’t happening.”

Meanwhile, Down guitarist Pepper Keenan is loathe to blame Pantera’s dissolution on Phil’s extra-curricular activity.

“Down were playing to about 300 kids at this time,” he shrugs. “I can’t see how anyone could think that would be a threat to Pantera.”

It would seem that Dime and Vinnie agreed, allowing Phil space to explore his urges. But when no compromise could be reached (“there was a communication breakdown and things went sour”, Phil admitted), Pantera was over and the Abbotts formed Damageplan. Then, the world at large was given an insight to just how deep the ill feelings ran.

Much has been discussed about the war of words that played out in the press in the aftermath of Pantera’s dissolution. In 2003, Vinnie Paul implied Phil was using again, saying he couldn’t “keep his fucking eyes open” while talking about ‘Superdope Ritual’ on MTV (“I’ve been fuckin’ stone-cold sober for fuckin’ two years... and you know, I can have a couple of beers, let’s get it straight,” Phil hit back ). The aforementioned interview that Phil gave this magazine in 2004 featured the quote about Dime that must still haunt him to this day.

“So physically, of course, he deserves to be beaten severely,” he said of the guitarist and his former friend. Sadly, we all know that Phil and Dime – and, indeed, Vinnie – would never get the chance to make amends with each other. And no metal fan could be blamed for wondering if time would have eventually healed that rift.

“I think the brothers really tried to come together to rekindle that thing,” offers Dez. “Philip did too, but it was too far gone. If something glows so bright, it’s gonna dim soon. It cannot continue to glow that bright for 30 years.”

While their legacy still casts a mighty shadow, it was a crushing shame that Pantera’s rule ended in tears.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.