Ted Nugent: The beast from 20,000 watts

It's 1976, and Ted Nugent is poised for greatness. The Great Gonzo has inked a solo deal with Epic – and his self-titled album is tearing out of the stores like a pack of wolves

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Ted Nugent is tuning up. Sort of. For him, you see, the practice most definitely does not consist – as it does for some – of gentle, tentative string pickings, quizzical expressions, slight cockings of the ear and delicate sound adjustments.

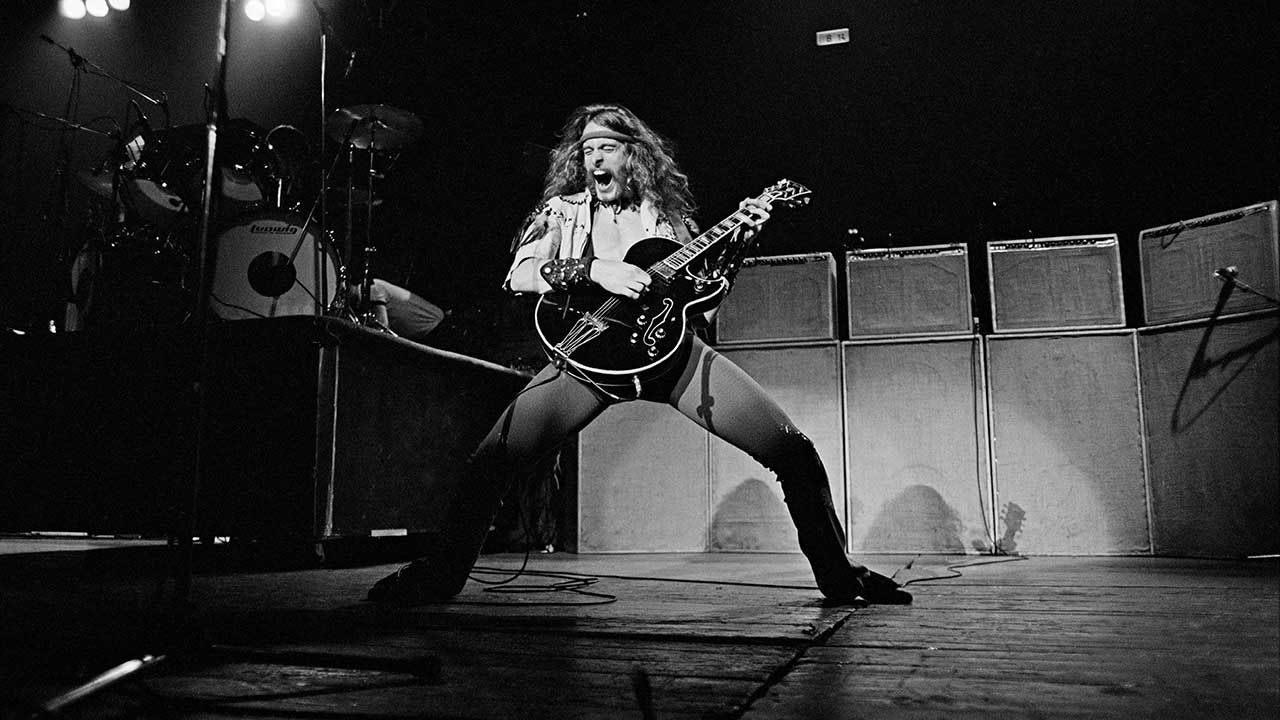

No sir. Not at all. Rather, even during an unceremonious prior-to-gig warm up session, Ted still brings the hammer down, attacking his Gibson Byrdland with a venom I thought he reserved for the stage alone. His right arm at once tensed, he strikes again and again, right to the heart of his instrument, getting that tone, grimacing with cruel satisfaction, and then cravingly coming back down for more. Much more.

The two of us are sitting in a bare, stark room somewhere in the bowels of Cleveland’s vast Richmond Coliseum concert venue. Nugent’s directly opposite me, handling his hefty, deep golden brown-coloured guitar as if it was a time bomb and he was a crazed bomb disposal expert – treating it with respect whilst recognising, with an evil glint in the eye, its potential to inflict real injury at any given time. And even with just the tiniest of amplifiers, the Nugent axe noise still manages to roar about the room like a Kawasaki at top revs, the riffs meaty and growling, the note-sustains long and unquavering, the playing speed both fast and furious.

And what’s this? Hold on, the Motor City Madman is actually singing as well. “Oo-ooh-ow-ow, oo-ooh-ow-ow!” Suddenly, spontaneously, Nugent begins to howl out wildly over the strident sounds. Then – ‘Well I don’t believe in social security, You see I want all my money now, Paying for the poor is obnoxious, That’s why I’m walking tall…’ – And so on, through several other delightfully self-opinionated verses. I never did manage to find out its title, but it was a great new tune.

And the Nuge didn’t stop there. That song finished, he then proceeded to debut a number called Live It Up (‘Can’t you see, I’m hap-happy, I just can’t stop, you know I’ve got to live it up’) which was in turn followed by Two Eyes For An Eye and Cat Scratch Fever.

I couldn’t believe my eyes or ears. An impromptu, completely off-the-cuff preview of four new songs by the mad, raw-meat-eating Detroit guitar hero. A blistering, bludgeoning, one-man band.

It could have been rather embarrassing, but instead it was utterly compelling, Nugent’s enthusiasm for his new compositions – “Ultimate rock’n’roll songs, the best I’ve ever written” – holding no bounds. I’ve never come across a musician so eager to share his music with people.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

I mean, I can’t think of any other who would allow a mealy-mouthed rock journalist to sit so close and allow him to hear numbers in their raw, formative stages of being played. All part of Nugent’s massive ego trip you might say, but that didn’t stop my estimation of the man growing quite dramatically all the same.

The Mohammed Ali of rock’n’roll, the guitarist is brash, massively overconfident, vain, swaggering and immodest – but endearingly so, nonetheless. And unlike many a performer’s proclamations, Ted’s boasts are seldom hollow ones. However far-fetched and ridiculous they may sound at the time of quotation, they have the uncanny knack of coming true in the end. And really, would you have it any other way?

With the last note of Cat Scratch Fever – some of you may remember it as the number with which Ted serenaded the audience during the equipment breakdown at the Hammersmith Odeon concert a few months back – echoing away, I decided that it was time to get to the brass tacks of an interview.

I first asked Ted for his retrospective views on his ’76 British concert debut. “It was cool,” he said, surprisingly kicking off with an understatement. “In fact, it was just like playing upper New York or lower Illinois. Everybody seems to have this great thing about going to Europe, but I’m not so sure.

“I think what we really got is not only humans who have been around a long time, but also rock’n’roll that has been around a long time.

“It’s like a new chick, y’know – you know that you’re going to be shooting off your rocks or whatever, but it’s still extra-special because it’s new.

“In Britain, I think everybody knew what ol’ Ted was going to do. Basically, they expected the world and I gave them the universe, but they knew that it was going to be rock’n’roll. There was no question of ‘I wonder what it’s going to be like’, they all had an idea; the people at the shows were rock’n’roll people and they had a good idea as to what was going to go down.

“They knew that we were going to come out there and give it to them – but what they didn’t know was that we were going to do it as incredibly as we did.

“They knew we were going to be smokin’ and they came to sweat and scream and punch each other and have a good time – good clean fun. I think everybody anticipated that. I think that’s what happened. I think it was special.”

Cleveland, Ohio smells bad. Heavily industrial city, its numerous grim, grey factories spew out smoke into the atmosphere 24 hours a day, a fact you’re reminded of every time you bother to take a deep breath. Within the awesome astrodome of the Richmond Coliseum, so large you expect to see clouds floating up in the rafters, the air tastes somewhat sweeter, courtesy of the dopers in the audience. But the atmosphere – this time meaning ambience – here is still pretty objectionable.

An overall air of heaviness pervades. Support band Rex had, unusually for them, failed to inspire riotous scenes, various crowd members being rather more intent on throwing fireworks at each other than watching the band on stage. One of the most appealing things about American audiences is the way, at the end of a group’s set, they invariably fish out their cigarette lighters from their pockets, put them on full, set them alight and hold them above their heads in kind of ‘thank you’ gestures. In pitch black US halls this can look a particularly impressive sight – thousands of yellow flames flickering around, from the stagefront right up to the top of the rear tier.

But now, it seems, the incendiary idea has been taken a stage further. In the Coliseum it was barely safe to sit with your collar up and your head sunk between your shoulders – fireworks were being tossed around like Molotov cocktails, exploding above you, at your feet and bouncing off your neighbour’s head to detonate mere inches away. Needless to say, I didn’t feel very safe.

And to give you some idea as to the size of the things being thrown – their crack-crackings could be heard distinctly throughout Nugent’s set, not a man renowned for tasteful restraint of volume. Toy pistol caps they were most certainly not.

Still, despite the belated July 4th celebrations going on around me, I decided to try and make it to the front of the stage to see the Nuge from where he should be seen, and not from block D, seat 142, way up somewhere in the rooftop. But security was tight to an extreme. A guy who tried to get into the arena just before me and who did not have a valid pass was literally beaten up by a power-mad ticket collector, and was thrown out on his butt.

And this happened while, just a few feet away, it looked like someone was having their eye poked out by a punk brandishing a lighted sparkler. I decided not to push my luck and retired to a relatively trouble-free corner of the venue, from where I could see Nugent’s band as a collection of quarter-inch-tall black blobs far away in the distance. But it was a smart choice. From here the sound was cacophony incarnate.

But surely it’s unusual, I commented to Nugent, for a British audience to welcome an American act with such wide-open arms. Usually, there seems to be a minimum of eager anticipation and a maximum amount of scepticism.

“I’m sure there was as much scepticism for us as for anybody else,” Ted conceded, “but that didn’t last long once we got out there. You got to realise that I’ve played in front of so many fucking people that I know what smokes, I don’t have to think about it.

“I think there’s still the regular anticipation – well, I call it anticipation and you call it scepticism.

“I just think that my stuff is so custom-fucking-made, is so great for a live audience, that they can’t help but dig it. I really think that.

“I mean, even at Reading where a lot of the press dared to try and criticise us, the audience were fucking standing up in their droves. And” – his voice reaching fever pitch – “did I or did I not predict the fucking rain a month ahead of time?”

You did?

“Yeah – I predicted it, except I was an hour late. I said it was going to rain as soon as we finished our set, then nobody, but nobody would have been able to follow us. But it began as soon as we started. Still, me and Mother Nature have our disagreements now and again.”

But didn’t you go on a little later than expected?

“Hey, that’s right! That explains why I was wrong – the band schedule got fucked up.”

Nugent is due back for his second European tour in February [1977]. Its schedule pays homage to the guitarist’s homing instincts, planned as it is in two fortnight-long stretches, with a week’s gap in-between.

“I can’t do anything too much, I don’t like to do nothing that much. I don’t fuck that much, I don’t sleep that much, I don’t eat that much…

“Two weeks, man, and then I get home for a while. I won’t push myself, you see. If there’s any reluctance at all to the schedule then I’ll stop it right there. Because as soon I start going, ‘Okay, book two more’ how am I going to play? How am I going to do it? I got to rest.

“If I’m looking forward to it, I’ll just wound the masses, but if I’m reluctant and I’ve been doing gigs for two weeks or over, I don’t really feel like doing any more, I really don’t.

“I’m sure my attitude has developed because of all the fucking days and nights and years and miles that I’ve done, from 1967 when I left home all the way through to 1974 when I still didn’t have a home and was just living for gigs.

“Now it’s two weeks on the road and then I’m ready for something else. I even spend the night alone once in a while.”

Changing the subject, I wondered when we might be able to expect a live album from Nugent. (He eventually delivered the goods with Double Live Gonzo! in 1978.)

“Live is special. Epic wants us to do a live album in fact, but I don’t really think that the time is ripe. I want to approach it special – I think live is special. If we’re going to do a live album, I really want to be live. I want to be able to scream ‘MOTHERFUCKERS!’ on the tape.”

Nonetheless, I contested, the live album has recently proved to be a great booster for people like Peter Frampton, Kiss, Blue Öyster Cult, Bob Seger and many more. Wouldn’t it be a good move, career-wise and business-wise, to have one as your next LP release?

“No, the next one’s in the studio,” Nugent replied emphatically, “we’ve got all the songs. And in any case, I think a live album should not only have pre-recorded tunes with a live thrust on it, but also newer stuff as well.

“But then again I realise too that live I’m able to call on some reserves – I can sing live like I can never sing in the studio. I’ve also played things on stage that, God, if I could play them in the studio the world would be licking my paws, man.

“I’ve played things live that were just fucking disgusting, I’ve played things live that were just the ultimate. I’m sure if there had been any blind people in the audience those times, they would have walked away from the gig seeing. But in the studio, somehow, for some reason, I can’t quite get a hold on it.”

A thin layer of snow covers Grand Rapids, Michigan, giving the rural place a peaceful, almost fairyland quality. The perfunctory multi-lane American highways are there in force naturally, but they cleave through some of the most beautiful American countryside I think I’ve ever seen. And even the air smells good, this time around.

The venue for the night was also infinitely preferable to Cleveland’s yawning abyss, being a college basketball dome, small in size by American standards, friendly, congenial and thankfully minus sadistic security personnel. I made it down to the front of the stage with ease – and there was Nugent’s band mere feet away, powering out the best heavy rock music that you’re ever likely to hear.

One thing that impressed me about Ted’s group is that, although they have grown in popularity quite dramatically in the States since I first went on tour with them last summer, they still remain infinitely accessible, having refused to get wrapped up in an Aerosmith-like star trip.

British drummer Cliff Davies remains the down-to-earth one-time jazz percussionist who played with If and who can’t really believe how well he’s landed on his feet. Guitarist and vocalist Derek St. Holmes actually seems to have been improved by success, by becoming more level-headed and sensible than when I last spent any time with him. Then he used to collapse senseless on floors, and threaten to get people shot in hotel bars. Even bassist Rob Grange, usually silent, something which I put down either to shyness or aloofness, emerged as a likeable fellow.

And Ted? Well, you know all about him. Nugent’s set, an hour long almost to the second, is now – unbelievably, perhaps – even heavier and more hard-hitting than before. Stranglehold, the traditional set opener, roared along like a Ferrari Berlinetta Boxer 4.4 doing 105 mph in first gear, and before you had time to catch your breath Just What The Doctor Ordered began, an instant cure for even the most major of rock’n’roll ailments.

Free For All featured St Holmes on tambourine and Ted wailing his demented battlecry: “AAAWWYEAHYEAHEAHHH!” After Snakeskin Cowboys ended, Ted stalked up to his microphone and asked: “None of you out there came to be mellow, didja? If you came to be mellow you can get the fuck out of here!” Resounding cheers. Next came Cat Scratch Fever and then Dog Eat Dog, a time to bite down hard, and Stormtroopin’.

Hibernation ended the set, Ted getting that note screaming in the centre of your cranium once again, and the two encores took us well and truly over the top. At the end of the first, Motor City Madhouse, Ted propped his guitar up against his amps so it screamed continuously. Then black curtains were drawn across the stage and the lights were turned way down low, so nothing could be seen. There was just the screeching going on and on, dulling senses you didn’t even know you had. And just when you thought you couldn’t take any more, the curtains were opened wide and the Nuge was on stage once more, pumping out Hey Baby.

It didn’t end there. At the end of encore number two, Nugent grabbed his ears and contorted his face, as if experiencing excruciating pain. Then he unstrapped his guitar and placed it on the floor, sank to his knees and bowed to his instrument, like it was an electric six-string Mecca. Then he was escorted off into the wings as if he’d had it, as if he couldn’t take any more, his guitar having battered him into submission. Nurse, the screams… What more can you possibly say, except – showmanship lives!

How about 1977, Ted? The year of your global conquest?

“At least. Why not? “Hey, listen man, I predicted all this shit 12 years ago. I was ready. But it’s impossible for a guy to do it by himself. Ol’ Ted, he needs a band that cooks and a manager to make sure that his record company tells the world that he is cookin’.

“When I sell out a place, the next day kids want an album of mine. I guarantee they want an album because when we play a concert they don’t forget about it in a day, a week, or even a year. They say: ‘Fuck, were you at that Ted Nugent concert? Wasn’t it great?’ And they want to prolong this feeling as long as they can – so they go out and buy my albums.

“My old record companies were so slow off the mark it was unbelievable, you just couldn’t buy the records in the stores. If they could have done what Epic are doing now I would have been huge three or four years ago.

“And would you believe that now my work pattern is slower than it’s ever been? I’ve never worked less in my entire life.

“It’s a sham – they want me to do a lot of interviews and go to Europe for five weeks continuously and I just tell them no. I’ve still got the energy of 12 people, but five years ago I had the energy of 42 thieves, the energy of an entire pack of wolves, literally. And I needed it, for the amount of work that I did.

“I’ll tell you what I used to do, I used to get the charts of all the US radio stations and I used to write them all letters to tell them when I was going to be playing their town. I’d say I’d be staying in such-and-such a hotel and that I would be glad if they would do an interview with me. Almost every one of them took me up on the offer.

“Now, I don’t do it any more. It’s not that I don’t appreciate your jobs; it’s just that now I have got different priorities.

“I don’t think I’m slacking off, I think I’m writing better songs than ever before, and I’m screaming better, although… I don’t think my guitar playing on the Ted Nugent and Free For All albums touches that on Tooth, Fang & Claw.”

Quite an admission. How come?

“Well, let me qualify that. I think that Stranglehold is the most inventive thing I’ve ever done and the last two albums – don’t get me wrong – had great guitar playing on them. But Tooth, Fang & Claw was more fiery and the track Hibernation had my best guitar playing ever on it.”

My last comment was cut short by Nugent in an appropriately crass fashion. Literal transcription follows:

“Ted, you seem to be on the threshold of something really big, really special, and…”

“On the threshold of becoming big? Listen, I’m already there, shithead.”

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.