At War With The World (And Themselves): The Story of Stone Temple Pilots

A tale of platinum-selling albums, drugs, booze and rehab, how the Stone Temple Pilots fell to earth before flying (fleetingly) high again...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Scott Weiland is drunk. Not ‘come-and-have-a-go-if-you-think-yer-hard-enough’ drunk or even ‘you’re-my- bessht-mate-you-are’ drunk, more of a ‘sedated-puppy-dog--embalmed-in-Jack-Daniel’s-and-nicotine’ stupor. It doesn’t really bother us. It’s a beautiful sunny Los Angeles afternoon

Scott Weiland is late.

This is not unusual. I have never had an encounter with the man where he’s turned up on time – although today’s excuse, it will transpire, is a little different from the usual ‘had some last minute business to take care of’. The singer arrives and looks up at us sporting a sheepish grin. “Sorry to hold you up, man, it’s taken me ages to find anything that fits,” he mutters in that familiar West Coast, stoned ‘Ratso’ drawl. He is definitely fuller in face and figure, looking less like the emaciated Thin White Duke of our last encounter in 2008, and more the backwoods lumberjack rocker of Core-era STP, but sans red goatee.

Article continues below“I’ve put on a few pounds,” he admits, pointing to his waist. “I’d like to lose a few. Rock stars always want to look skinny. The idea is to look like you’re doing drugs but not do drugs. It’s been quite some time since I’ve done them. I drink, and that puts some weight on you.”

By the time he reaches the top of the stairs he has ordered a large Scotch and reacquainted himself with the rest of the band: bass player Robert DeLeo – who like his brother, is tall, lean and surprisingly polite – and drummer Eric Kretz, an explosion of bleached curly locks and pointed features, resembling a Spitting Image puppet of Owen Wilson.

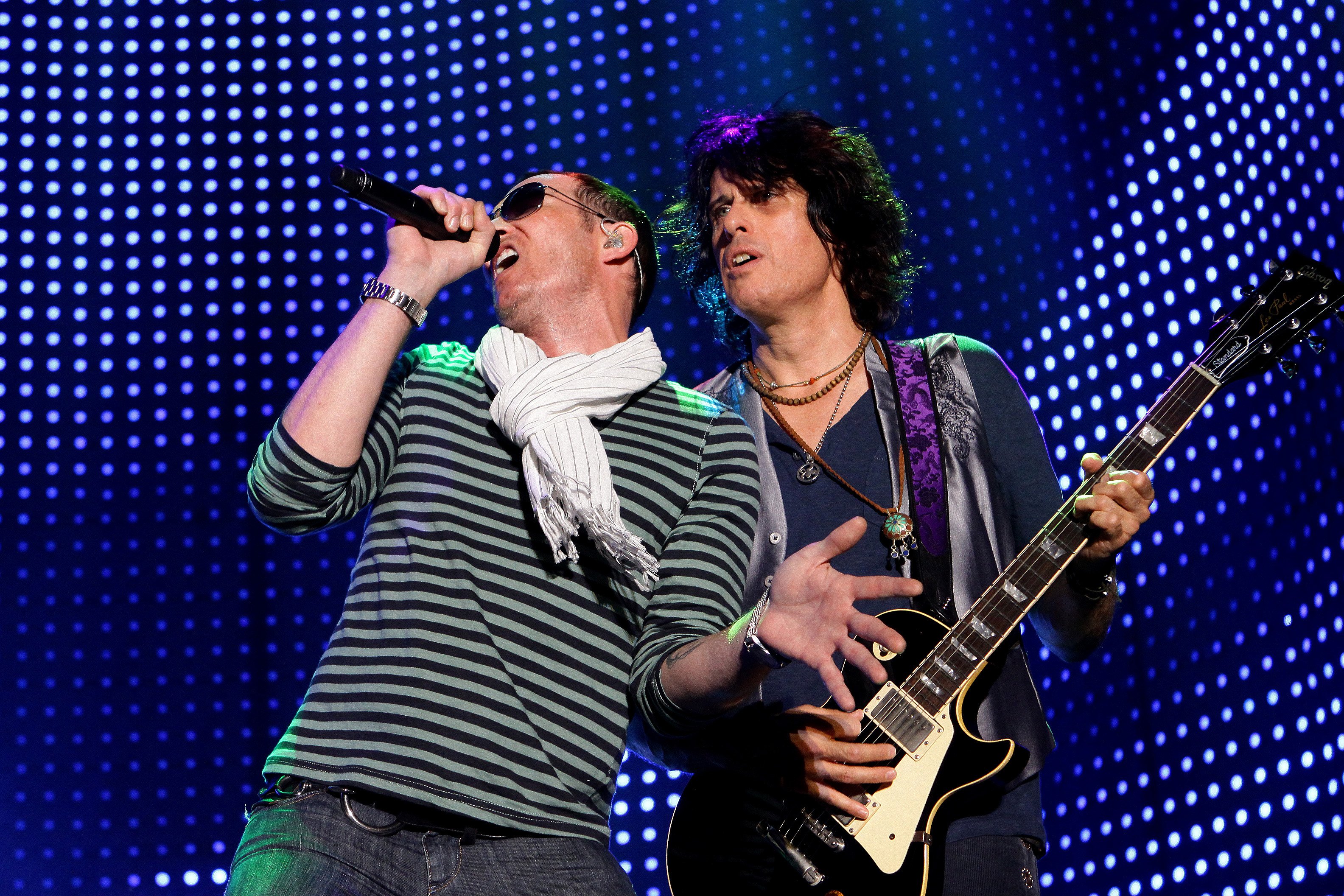

As a coterie of personal assistants, PRs and management hover manically trying to look like they actually need to be there, CR photographer Ross Halfin corrals the group into a line-up for a shot. As certain members’ eyes roll up in mock exasperation at the sight of their slightly dishevelled singer, Weiland miraculously transforms into rock star mode, staring intensely at the camera and looking uncannily like a psychotic Fight Club-era Edward Norton. He stays in The Pose between shots, to quite unnerving effect.

The session moves outside and Weiland suddenly stops, looks down and points to his feet. “Oh, look man,” he says, “I’ve got two different shoes on.” Both shoes are black but they are, indeed, from different pairs.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

He berates his beleaguered assistant for this faux pas and then heads off with Halfin, again delivering the money shot. At the end of the day he makes a quick exit with a lackey and two Johnny Walker Blacks to go. Scott Weiland is a star – of that there is no doubt.

While everyone expected a worst-case scenario since the very public and acrimonious dissolution of Velvet Revolver, Weiland has managed to bounce back, although the last couple of years have been clouded by tragedy (the death by overdose of his brother Michael), divorce (from model Mary Forsberg) and a brief stint behind bars for driving under the influence.

And although the current STP re-formation has been a sell-out success and their latest album looks like being a career best, there have been some worrying episodes involving Scott, including incoherent interviews splattered across YouTube, a Tyleresque tumble during a show in Iowa, and another disastrous performance in the DeLeos’ home town of New Jersey where the band came on an hour-and-a-half late and fans claim to have seen one of the brothers outside Weiland’s bus screaming: “Get out, Axl!” It hardly comes as a shock when the Anglophile frontman tells me that one of his favourite artists is Pete Doherty – they both seem to be singing enthusiastically from the same hymn book.

Did his previous addictions affect him and STP the first time around?

“I like to think of myself as a responsible individual,” he says, “and when I give my word that I’m going to be somewhere, I like to keep it. And when the band started being unaccountable and not making appearances it affected me, deeply. And there’s nothing worse than being helpless.”

“It wasn’t always the smoothest of rides,” agrees Robert DeLeo. “I think we all grabbed onto our vices.”

- Scott Weiland can’t be replaced, say Stone Temple Pilots

- The Tragic Life And Unavoidable Death Of Scott Weiland

- Velvet Revolver had too many egos, says Weiland

- The chaotic, crazed story of Guns N' Roses' Use Your Illusion

While Robert and Dean DeLeo present a more sober, cautious overview of the band’s chequered history (verbally walking on eggshells around their frontman’s temperament and peccadilloes), Weiland, as usual, dominates the proceedings with his upfront frankness and brutal honesty. At times he comes across as an equally enlightened and anxious soul that seems to find total sobriety a frightening and arduous prospect, which is probably why he took to Class A drugs with such a kamikaze enthusiasm in the first place.

“Heroin is great at the beginning, because it takes away all of your emotional fears,” Weiland agrees, while nervously playing with a packet of Camels (another vice he is trying to quit at the behest of his children). “I didn’t give a shit about anything. I used to be afraid to walk into public places, something which again I don’t like to do now since giving it up.”

By the time Scott had his first experience of opiates during a tour in 1994, STP were already a couple of years into their career. Signed to Atlantic a year after the advent of grunge in 92, their debut album Core represented everything that was innovative and exciting about the Seattle sound in a more homogenised, commercial format. It sold millions and the band were almost instantly treated with suspicion and disdain by the critics (they were also simultaneously voted Best New Band by Rolling Stone readers and Worst New Band by the music critics).

“Obviously I’m not naive to it, the timing of Atlantic signing at the start of the grunge movement,” sighs Robert. “ I don’t think our intention was ever to be grunge. When we first got together our focus was always songs. We just wanted to write great songs.”

In a career that spanned nine years and in which they produced six albums, STP managed to baffle both fans and critics with a sound that reflected a wide-ranging sphere of influences from Zeppelin, The Doors and the Stones to bossa nova and even the Carpenters. They rapidly ascended from being predictable purveyors of generic rock to creators of sublime, anthemic, multi-textured and at times psychedelic anthems, selling shedloads of albums in the process.

Scott’s substance problems began to surface as early as the second album, Purple, which like its predecessor was recorded in a mansion (in retrospect a homage to the Stones’ Exile On Main St), this time in Atlanta. For the moment the drugs did work and although still heavy, the band experimented with different rhythms and acoustic material.

“During this period heroin gave me this ability to distance myself from the creative process and thereby gave me the strength and courage to try new things,” admits Scott. “But after years of taking it, it just becomes all- encompassing, it becomes this black ooze that covers your heart and you can’t feel the music any more. But, I don’t know… Part of me felt I couldn’t be creative unless I was high.”

Although Purple was a critical and commercial success, celebrations were muted when on May 15,1995, Weiland was arrested for the possession of a crack pipe, heroin and cocaine plus various other drug-related offences. This resulted with a mandatory stay in rehab, the first of many in the rock star’s troubled career. By now the band’s music was being overshadowed by Weiland’s burgeoning addiction which was making the headlines and attracting the attention of the boys in blue. With some very public busts it seemed like he was either enjoying his notoriety or in self-destruct mode.

“Well, I didn’t have one of those fancy Hollywood dealers that came to your house and sold you a couple of ounces,” he says with a grimace. “I’d go out into the streets where you’d drive up to a corner and be mobbed by a group of border brothers – illegal Mexicans selling heroin-shouting, ‘Chieva! Chieva! Chieva!’ and you’d go ‘Alright!’, buy it and speed off. But the cops got wise to that.”

Things got predictably worse, with more busts, cancelled dates, rehab et cetera. By the time they released their fifth album Shangri-La Dee Da in 2001 things came to a head when Weiland and Dean nearly came to blows after a show.

Scott: “We were staying in different hotels, and by this time Dean was using; he was getting cocaine FedExed to him. It all culminated in this dressing room where we threw punches at each other. If it wasn’t for our minder we probably would have done some damage. I would have gotten the best of him.”

A couple of days earlier the two of them had been sat in a motel sharing jokes and smoking crack, now it was all over. Everybody left in separate cars and went their own way.

“When you think about it, it’s really textbook 101 of what happens,” sighs Robert. “There’s a blueprint that follows musicians around.“

“It’s all the same shit, isn’t it?” exclaims Dean with a raucous laugh. “EGO! Fucking ego. You got to check that monkey at the door. I think it’s nothing but destruction. It’s amazing that people in their 40s, 50s and 60s are still fucking carrying on like this.”

It was at this point, Weiland claims that he hit an all-time low, when his wife Mary left him, taking their son Noah. “I’d been clean for a year-and-a-half after the birth of my son and then I went back to using,” he recalls with a palpable shudder. “Although we used to be junkies together, Mary quit doing drugs after we had our son, and she wouldn’t let me come down to see him if I was loaded. And of course if you’re doing heroin you’re loaded every day.”

A lifeline came in the form of Slash who invited Scott to join Velvet Revolver. The band, all recovering addicts and alcoholics, gave him time to sort himself out in the now very familiar surroundings of residential care, where he stayed for six months, after which he graduated to a sober living house. He credits this experience for keeping him sober for four years.

Scott’s career trajectory with Revolver was pretty similar to STP. First album Contraband debuted at number one in the US charts and went on to sell three million copies. By the time they were touring the less successful follow-up, Libertad, the cracks (and crack) began to appear. Everyone with the exception of guitarist Dave Kushner relapsed and suddenly various members were at each other’s throats. Weiland and Matt Sorum waged a war with each other via the internet and this came to head at a show in Glasgow on March 20, 2008 when the two confronted each prior to an encore.

“I was threatened physically by Matt on the stairs,” recalls Scott. “It was at that moment that I decided I’d had enough and pulled a Ziggy Stardust move and announced to the audience ‘you are very fortunate to see the last tour of Velvet Revolver’.”

Although it came to a dramatic end Scott still values his time with the band and still has a great respect for Slash. “I mostly have positive memories from that time. I’d like to think that Velvet Revolver put a bullet in nu metal’s heart. I understand where Slash is at right now doing his solo album. I read an interview where he said, ‘It’s kind of nice not having to be in a democracy right now’. Democracies can be very challenging and weathering.”

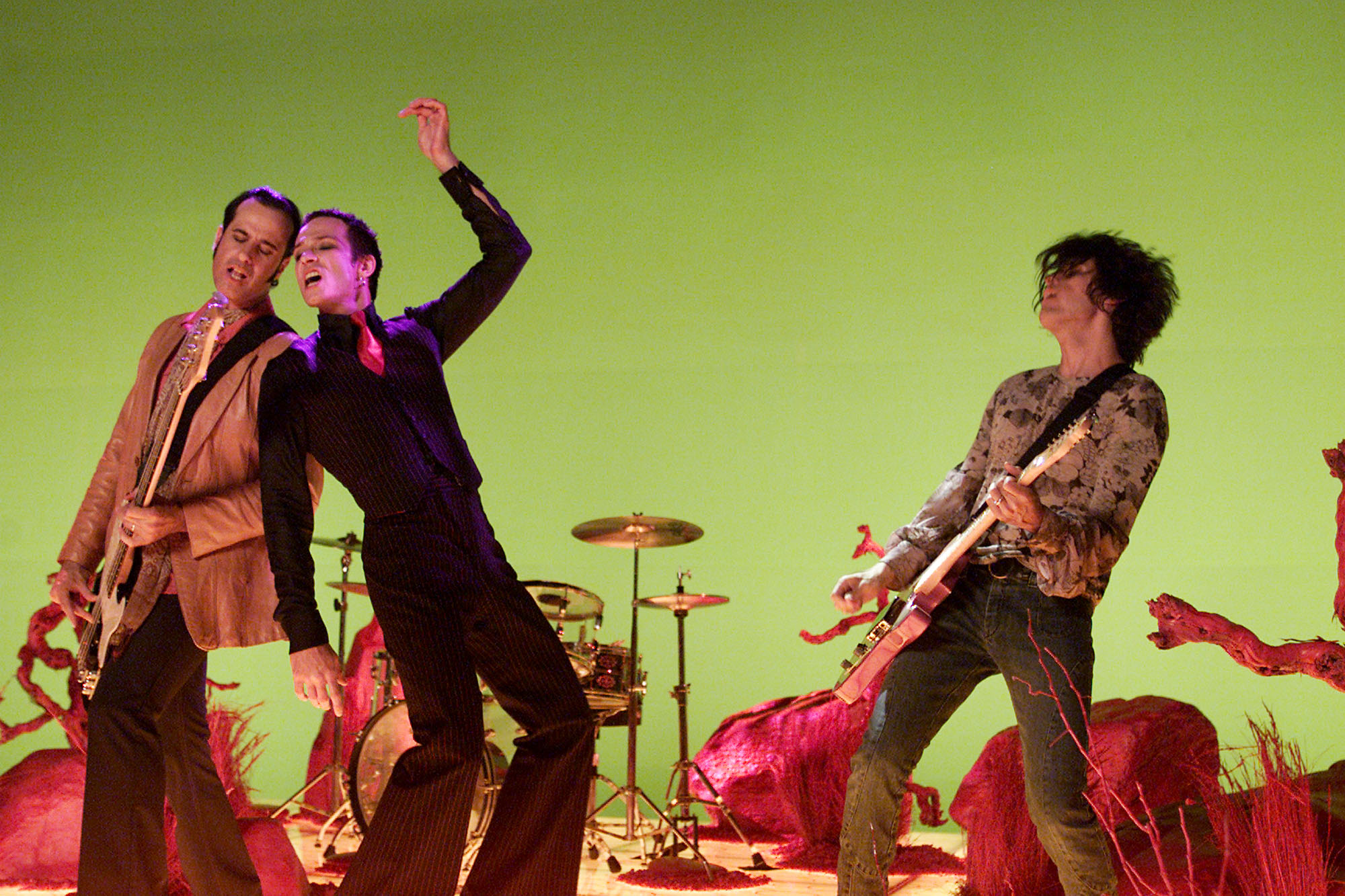

This brings us neatly to the newly reformed Stone Temple Pilots. Prior to his final tour with VR, Scott received a call from Dean telling him that a promoter had offered STP $1 million dollars to play Coachella and if this worked they could follow it with a 10-day festival mini-reunion. This was the second time that he had contact with Dean since STP folded.

“The first time I saw him was when I was recording with Velvet Revolver and it was uh… very respectful,” Scott says with a hint of sarcasm. “There were still resentments. It took a while for Dean to get sober. He called me one night and said, ‘You know what? I’m sorry that I made you a scapegoat for all those years when I was doing the same things you were’.”

Although Slash gave his blessings for the festival dates previous commitments prevented it from happening. “Scott kind of expressed that things were a little unsettled in the Velvet Revolver camp,” recalls Dean, “but I wasn’t going to get in the middle of that. I was really happy for his success in the band. I told him about the festivals and asked him how he felt about it and the next thing you know, he leaves VR and we’re on a bus doing a 65-date tour.”

Since then they have recorded a stunning comeback album, self-produced with some additional mentoring from Don Was. It’s unburdened by past luggage and has an almost celebratory contemporary retro feel, partly inspired by Dean dusting off his classic rock collection and his recent infatuation with the kitsch sub-genre Sunshine Pop.

Weiland looks and sounds like a man with a mission. “It felt like it was unfinished business,” he says of the reunion. “STP has a legacy. We sold nearly 40 million albums. It’s something that for nearly two decades now has been ingrained into people’s lives and pop culture, which is what we set out to do.”

“I don’t think it ever ended,” beams an ever-optimistic Dean. “I never felt that things were falling apart, I felt there was a time that we needed apart. We were shoulder to shoulder for nine years and when you’re living in such tight corners, doing the same thing for almost a decade; you grow tired of one another’s routine. But STP never ended. I think we’ll call it a respite.”

Scott Weiland is back. But for how long it’s difficult to tell (not for long, as it turned out. He was fired in 2013, and replaced by Chester Bennington of Linkin Park). He wears the mask of celebrity well, but at times it seems to melt in his face and he stops looking like he’s in control. As the interview comes to a close there is one final question: Mr Weiland, are you really that difficult to deal with?

“Absolutely not! I’m a very easy person to deal with. Nowadays I have enough confidence in myself that if I don’t like something then I won’t do it. I’m 42 years old. I still try to put on a great show. I move around like I did when we first started touring, I’m drenched at the end of the set. And mostly, regardless of what bands or journalists think of us, I want to be pleased with what I’m doing, I want to be happy.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #146.

The Grunge Quiz: how well do you know the 90s most subversive genre?

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.