Sir Lord Baltimore: the forgotten story of America’s original heavy metal band

They toured with Sabbath and laid the foundations for stoner rock. This is the chaotic tale of Sir Lord Baltimore

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

They were Fuck Barbarians from Planet Garbage, come here to splinter skulls; a proto-thrashing teenage bloodbath sealed on wax. Over two albums and just 29 gigs, they defined a genre and left tantalising clues about the future of rock.

Sir Lord Baltimore’s music was so alarmingly intense, it required a whole new terminology to explain it – ‘heavy metal’, naturally – while their instrument-smashing, chuggernaut on-stage prowess was so fearsome that even Black Sabbath resorted to (ahem) sabotage to keep up with them.

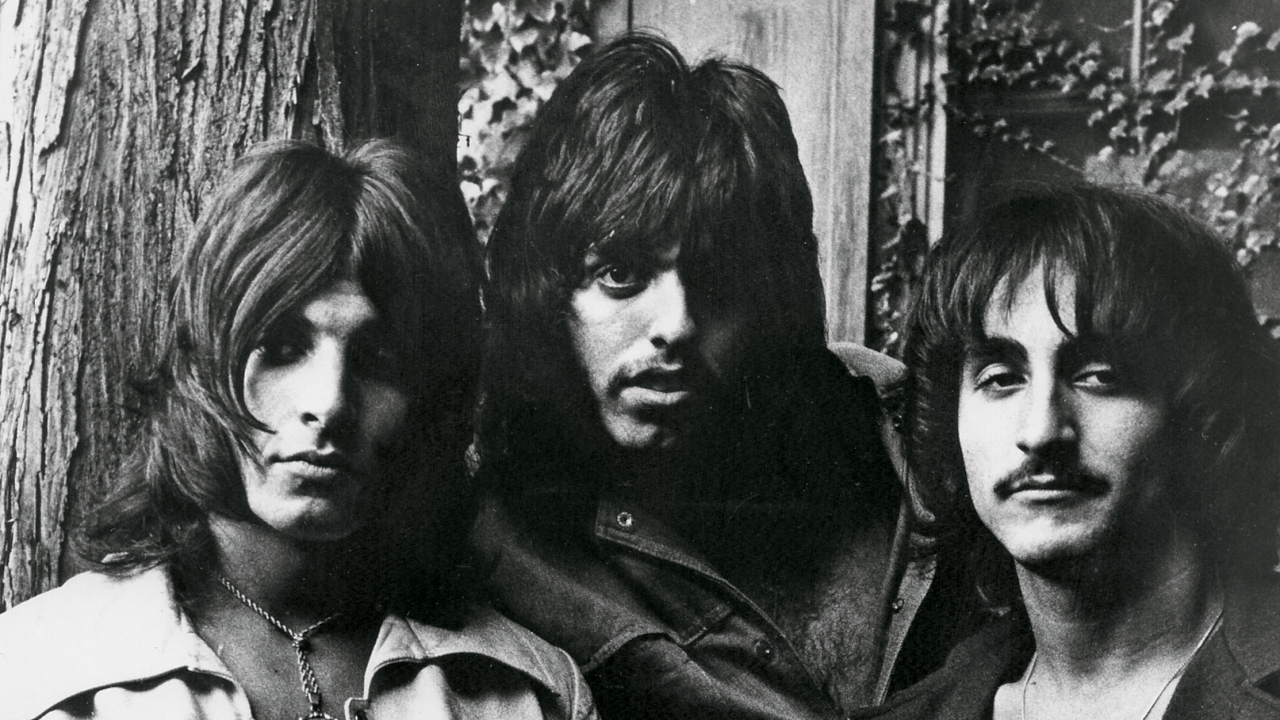

But underneath the neanderthal war-whooping were three freaked-out adolescents from Brooklyn, New York, green but eager, shoved into the spotlight much too early and let loose to flail away in the pantheon of the rock gods. They never stood a chance. Still, their long shadows still loom, and their legend continues to grow. The ultimate cult band, as influential as they are stubbornly obscure, Sir Lord Baltimore remain the original heavy metal kids.

John Garner, Sir Lord Baltimore’s singer, drummer and founding member, was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. You can hear it in his accent and his no-nonsense delivery. He speaks about his teenage years in the 60s like most people growing up in that heady time do: with reverence and awe.

“I had a lot of influences in the black arena of music,” he says. “Sam Cooke, Chubby Checker. I used to listen to all the Motown stuff and I used to sing to them. I used to do the twist, man. It was a great era.”

Garner began playing drums and dreaming rock’n’roll dreams in the late 60s. One afternoon in 1968 he met a flashy rich kid with a guitar who would change the course of his career and, ultimately, his life.

“I met Louie [Dambra] in front of our high school. He was sitting in his Porsche,” he laughs. “He had some dough. Anyway, I met him and I said: ‘I heard about you.’ And he said: ‘I heard about you, too.’ So I got in his car and I said: ‘Well, let’s play. Let’s do somethin’.’ So we started rehearsing in my basement, just jamming. And then I read an ad in the Village Voice that said: ‘Heavy band needed for recording.’ So we responded.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Garner, Dambra and bassist Gary Justin – another high school chum – took a fateful trip into the city. At Smile Studios they met A&R man and fledgling producer Mike Appel, and gave him a dose of their teenage thunder. “We put together four songs that were sorta half-assed,” Garner remembers, “and he freaked out. He loved us. Mike wanted to immediately record us, because he saw potential for him to make out on a deal. And you know, I was 18. What the hell does an 18-year-old know about the music business? And so we signed.”

Along with the production deal came high-powered manager Dee Anthony. Anthony worked with megawatters like Joe Cocker, the Faces and ELP, and had a simple plan for the band: hit the stage running, and don’t look back.

“He was a pretty powerful fella,” Garner says. “Our first show was playing Carnegie Hall. Our second was the Fillmore East. That’s pretty unheard of.”

Not a bad schedule for a band that didn’t even have a name yet.

“Our producer, Mike Appel, named us,” Garner remembers. “He was looking at this movie with Paul Newman and Robert Redford – Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid. Both of those guys say the name ‘Sir Lord Baltimore’, because they were running away from an Indian tracker named Sir Lord Baltimore. I said: ‘Okay.’ I mean, who gives a shit what the name of the band is? Especially back then. It was the British invasion, so people might have thought we were English. I didn’t care.”

The newly christened band signed to Mercury Records and began work on their first album, the manic, hard-charging Kingdom Come, at Electric Lady Studios. By the time they were through and the album hit the bins in 1970, ‘metal’ was not just an element, but also an art form.

“We were the first ones to be called ‘heavy metal’, says Garner. “It was in an issue of Creem magazine. That’s a fact.”

Indeed, Garner’s story checks out. ‘Metal’ Mike Saunders, later of garage thrashers the Angry Samoans, reviewed Kingdom Come in the May ’71 issue of the magazine, and pegged SLB as possessing all the “heavy metal tricks in the book”. As well they should – they invented them. Garner places most of the blame for their sonic excess on their youthful enthusiasm.

“Well, I loved Jimi Hendrix. I loved Led Zeppelin, but who doesn’t? But really, we had our own style, because we were frantic. We were very young, I was 18, and we were super-high-energy. I sang so hard I’d almost pass out. I used to go through metal foot pedals, break ’em in half. Cymbals, forget about it. I used to bang the shit of them and split them in half. We were intense.”

With an arsenal of proto headbangers like I Got A Woman and Helium Head in their war chest, Sir Lord Baltimore hit the stage for some very high-profile gigs.

“To be honest, I felt we should have been nurtured and played some little dumb shows here and there, not play Carnegie Hall for our first gig,” Garner says. “You know what happened? Gary was running back and forth, he was so excited, he pulled out his bass cord twice. And Louis was so nervous that his legs were shaking. I was the only one who was cool. I had the confidence. For me it was wonderful, even though I ripped through my cymbals. They just fell apart from hitting them so hard.”

Carnegie Hall was followed quickly by a second gig, at the Fillmore East. Forced to sing and bash his drum kit over 350 watts of ear-bleeding, Sunn-sponsored amplification, Garner nearly wiped out mid-song. “On stage, I screamed so loud I almost blacked out,” he remembers. “So I said: ‘Whoa, I gotta take it easy here’. Being on stage was the best high I ever had. It was a musical high.”

In terms of sheer sonic tonnage, Sir Lord Baltimore had very few peers. So it seemed like an obvious move to team them up with Brit doom-gods Black Sabbath for a US tour. Unfortunately, it did not end well.

“So we went on tour with Black Sabbath. We went to the Virginia Dome. My manager made a deal with their manager to let us use their PA system. That was a big mistake. We were playing to over 6,000 people and we were doing a great job. And all of a sudden the power went out. Somebody pulled the plug. Then we started again. People were going crazy, they loved us. And they pulled the plug again.

“Three times they pulled the plug on us. Now, who knew people were gonna be that treacherous back then? We were into love, peace, and happiness. What’s this shit? Unfortunately they came from Birmingham, and I guess they didn’t have any manners. If we knew that, we would have hired some strong guys to sit by those plugs and beat the shit out of anybody who tried to pull ’em.”

Amid all this madness, Sir Lord Baltimore managed to make it back into the studio and released another, self-titled album just a few months later. The second album was thicker, dustier, a drug-buzzy lurch that can easily be traced back as the patient-zero of stoner rock.

“Truthfully, it was,” laughs Garner. “Because we were stoned a lot.”

Since their inception, Sir Lord Baltimore were told they were five or 10 years ahead of their time. That’s great for establishing a legacy, but terrible for paying bills. “People always told us that,” Garner says. “Always. We were original, we didn’t sound like anyone else, and we were always ahead of what was happening. That’s great, but it’s no help when you’re trying to make some money as a band.”

Compounding their troubles, Dambra and Garner ran into personality conflicts. Drugs didn’t help matters any.

“I mean, it could have been cool, you know,” Garner laments. “If nobody took drugs and if Louie wasn’t such an egomaniac, we could’ve been rich. All we had to do was stick together.”

By the mid-1970s, Sir Lord Baltimore were limping along. The records didn’t sell, the gigs were drying up, and the band was dysfunctional. They took one last stab at recording, in 1976, but the songs were left unfinished. And Garner was unceremoniously dropped from his own band.

“Mike Appel sat me down in his office and he said: ‘You’re always asking questions, you want to do this, you want to do that.’ I said: ‘Yeah, well what’s wrong with that?’ So he fired me. What he wanted was puppets. Gary and Louis fell right into that, because he was paying them to move out to California. The funny thing is, they started playing flamenco music. They had a timbale player. They sounded like Cat Stevens. I was like:, ‘What the fuck happened?’”

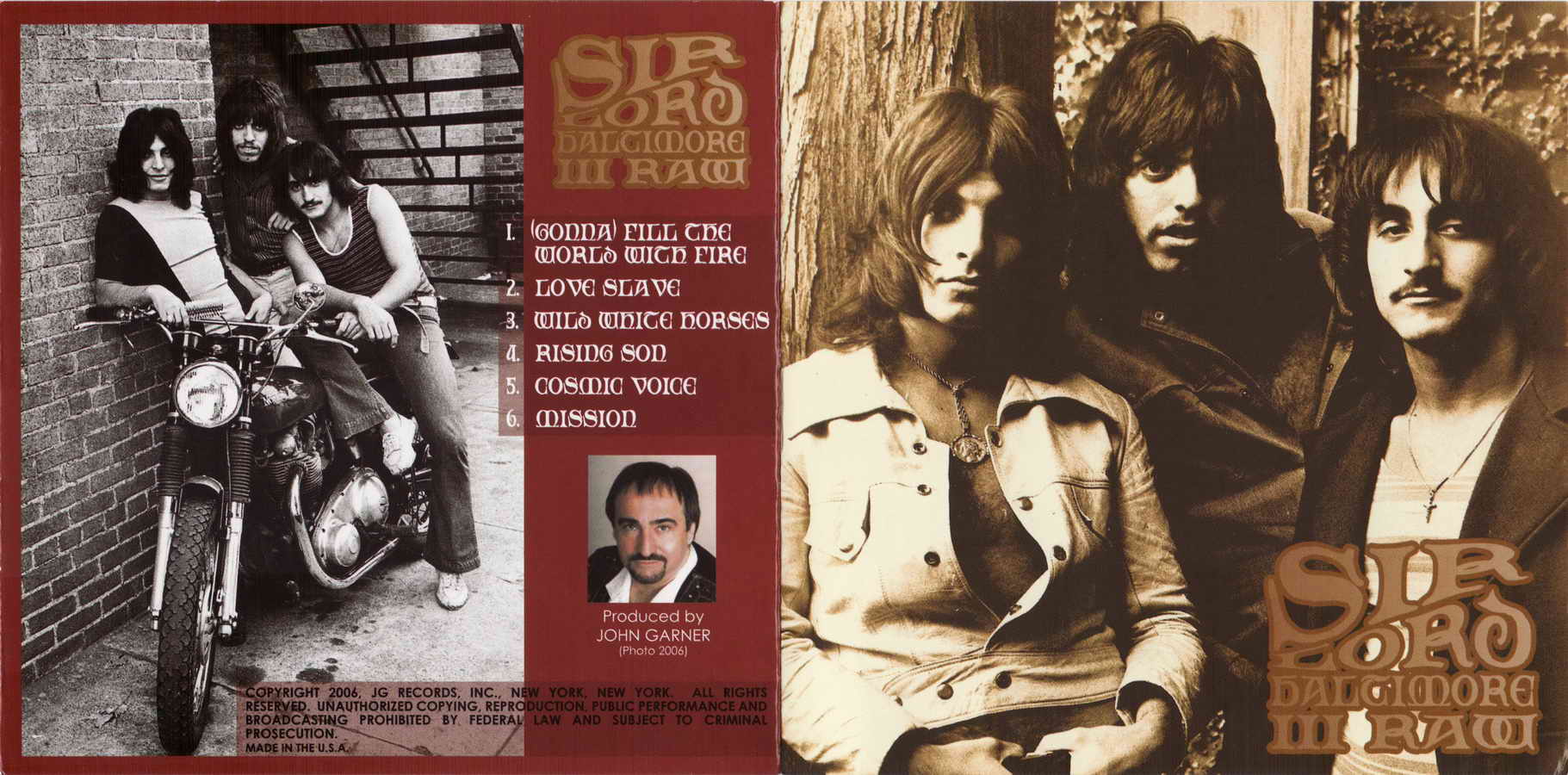

And that, essentially, was that. Garner fitfully tried to revive the band over the ensuing decades, and in 2006 he finished off their mid-70s album, self-releasing it as Sir Lord Baltimore III Raw. He kept the bludgeoning riffola, but changed the lyrical content to reflect his Christian beliefs. “Basically, I said that heavy music has a lot of influence with its Satanisms and its vampirisms and its sewn-up mouths,” he explains, “but what’s heavier than the power of God?”

Over the decades Louis Dambra had also found religion, and became a pastor in Los Angeles. Despite their spiritual outlooks on life, neither has been able to resolve their differences.

“I don’t talk to Louis any more,” says Garner. “He’s an asshole. He was hard to work with since the beginning. I mean, I didn’t help by taking so many drugs, but still, it was a heartbreaker for me that we didn’t get to make things happen while we were together.”

Every Sir Lord Baltimore reissue released in the past few decades – and there have been many – are, Garner contends, bootlegs. Forty years later, he has still not made a dime for his efforts as a proto-metal shocktrooper. As the years wound on, he found himself playing sideman in perpetual up-and-comers The Lizards, managing wedding bands, and working for the New York Department of Sanitation. Not all of those years were great. Some were pocked with lean times and health scares. But for most of those years the tantalising possibility of a Sir Lord Baltimore reunion, a chance to right all wrongs, always loomed just over the horizon.

When the wedge between Garner and Dambra became too deep and profound, Garner was forced to face facts: Sir Lord Baltimore was over – for good. For years he quietly seethed, angry about the rip-offs, the hassles, the lost opportunities. But SLB’s status as early-metal pioneers never wavered. The band’s legend is cemented. Like The Stooges, the MC5, like Blue Cheer or the Velvet Underground, Sir Lord Baltimore will never be lame, never be tame, never be square, always be shockingly ahead of their time. And that matters, perhaps more than any fistful of peanuts the band might have acquired were their contracts in order.

It’s taken some time, but Garner is finally ready to accept his role as the curator of Sir Lord Baltimore’s legacy.

“I will admit I had some misgivings about it all,” he says, “and I was angry about all the rip-offs. But it’s true, I’ve got a legacy. So I got robbed. Big deal,” he shrugs.“That’s yesterday’s paper, man.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock magazine #181.

Classic Rock contributor since 2003. Twenty Five years in music industry (40 if you count teenage xerox fanzines). Bylines for Metal Hammer, Decibel. AOR, Hitlist, Carbon 14, The Noise, Boston Phoenix, and spurious publications of increasing obscurity. Award-winning television producer, radio host, and podcaster. Voted “Best Rock Critic” in Boston twice. Last time was 2002, but still. Has been in over four music videos. True story.