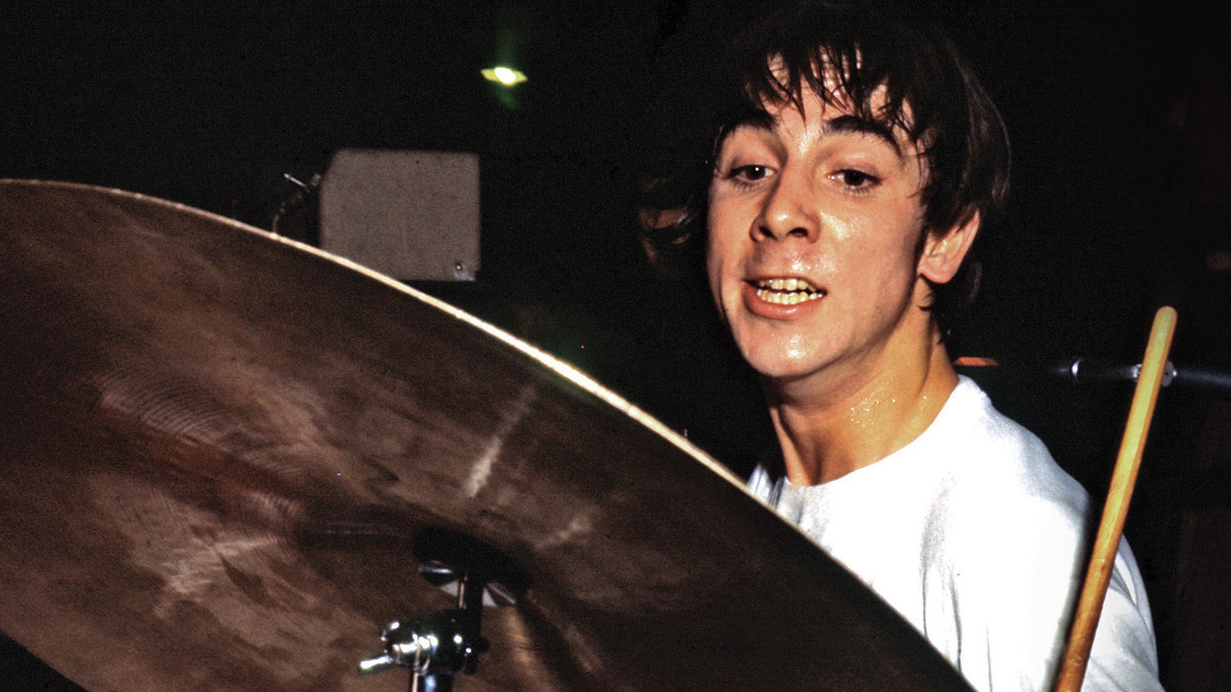

Keith Moon: the man behind the myth

In an exclusive extract from the new book Keith Moon: A Tribute, Kenney Jones, Pete Townshend, Richard Cole and Mick Avory remember The Who’s great drummer

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Friend

By Kenney Jones

Small Faces / Faces / The Who

Article continues below“What’s the first thing that comes to mind when I think of Keith Moon? The first thing is I wish he was still here. I wish I could pick up the phone and arrange to meet up with him this afternoon. Keith was a very close friend and he is very much missed.

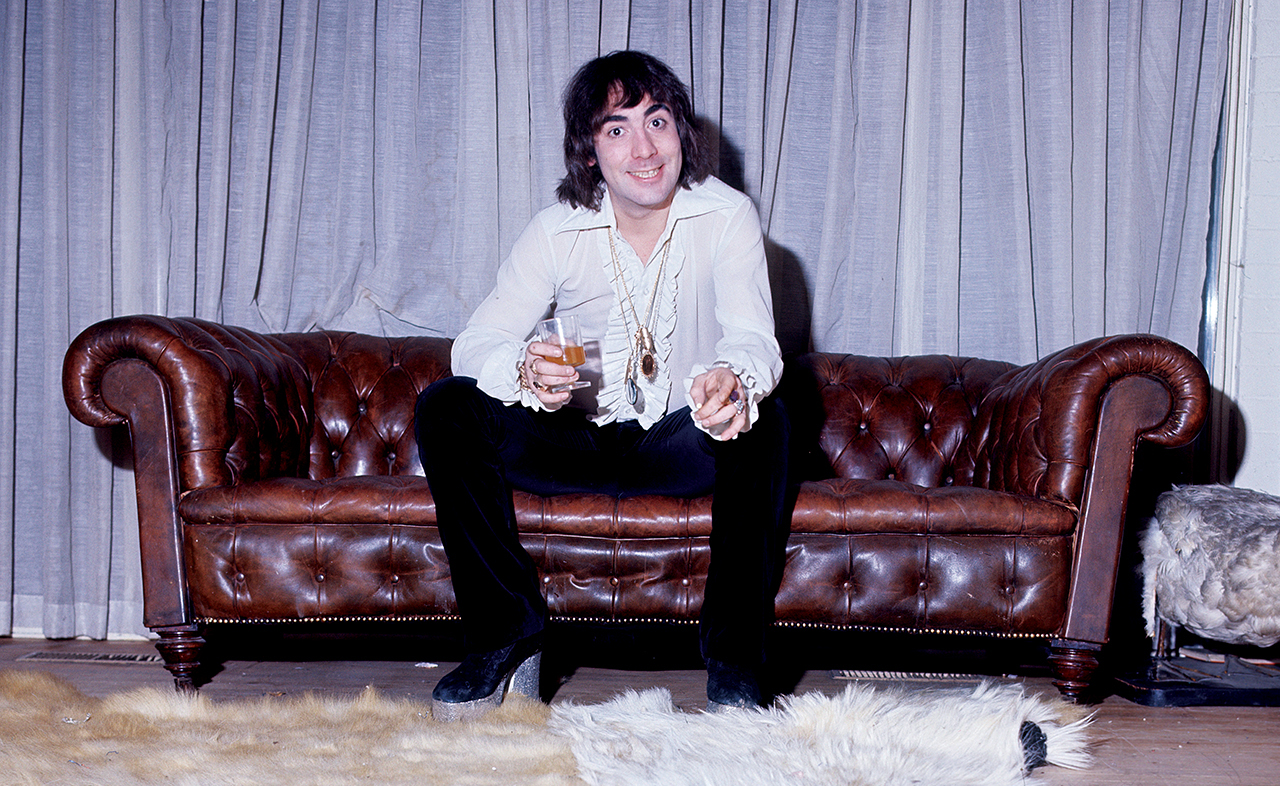

“I saw Keith at the Buddy Holly film party and that night he was still fun to be around. We had this relationship where he would never take the piss out of me. We could sit and talk without him feeling like he needed to be on show. I mean, I saw plenty of Keith Moon ‘the showman’ too; you couldn’t stop him, it was in his genes. We talked frankly about things and about both of our new projects. I was just starting up a new band with a couple of American guys and he was very interested. We were both talking very enthusiastically about what each other was doing. I remember it being a very positive conversation. Then we went off to watch the film and then I saw him again in the foyer on the way out.

“The next morning I got up and turned on the TV and the news about Keith’s death was all over it. ‘Keith Moon found dead from a drug overdose.’ I didn’t believe it, I couldn’t believe it. I thought it was another one of Keith’s hoaxes. I just kept telling myself that it couldn’t be real. I mean I had only been with him a few hours earlier. But sure enough as the day developed, sure enough the news of Keith’s death was true.

“From what I could gather he had taken one of the pills that he was on, gone to sleep, then woke up and thinking it was the morning, he took another one and this was dangerous to the extent that it slowed his heart down, until it stopped. So in the end it was an indirect overdose of drugs that contributed to Keith’s death. Now they may have found some other bits and bobs in his body, but I must say he really was trying to keep himself together. And what I like to think is that he would have been on the road to recovery. I suspect he would have had a couple of relapses, because that was Keith, but I think he would have kept going in the right direction and made larger leaps as time passed. That’s what I like to believe.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“When The Small Faces had our first hit record, The Who had only had theirs a few months earlier. The press at the time thought it would be good if they made The Small Faces and The Who out to be rival bands. I think they based this on the fact that we were both from opposite ends of London. The funny thing was that because we were from the East End we thought anything outside of the East End was posh. So we thought The Who were posh. Little did we know what Shepherd’s Bush was really like.

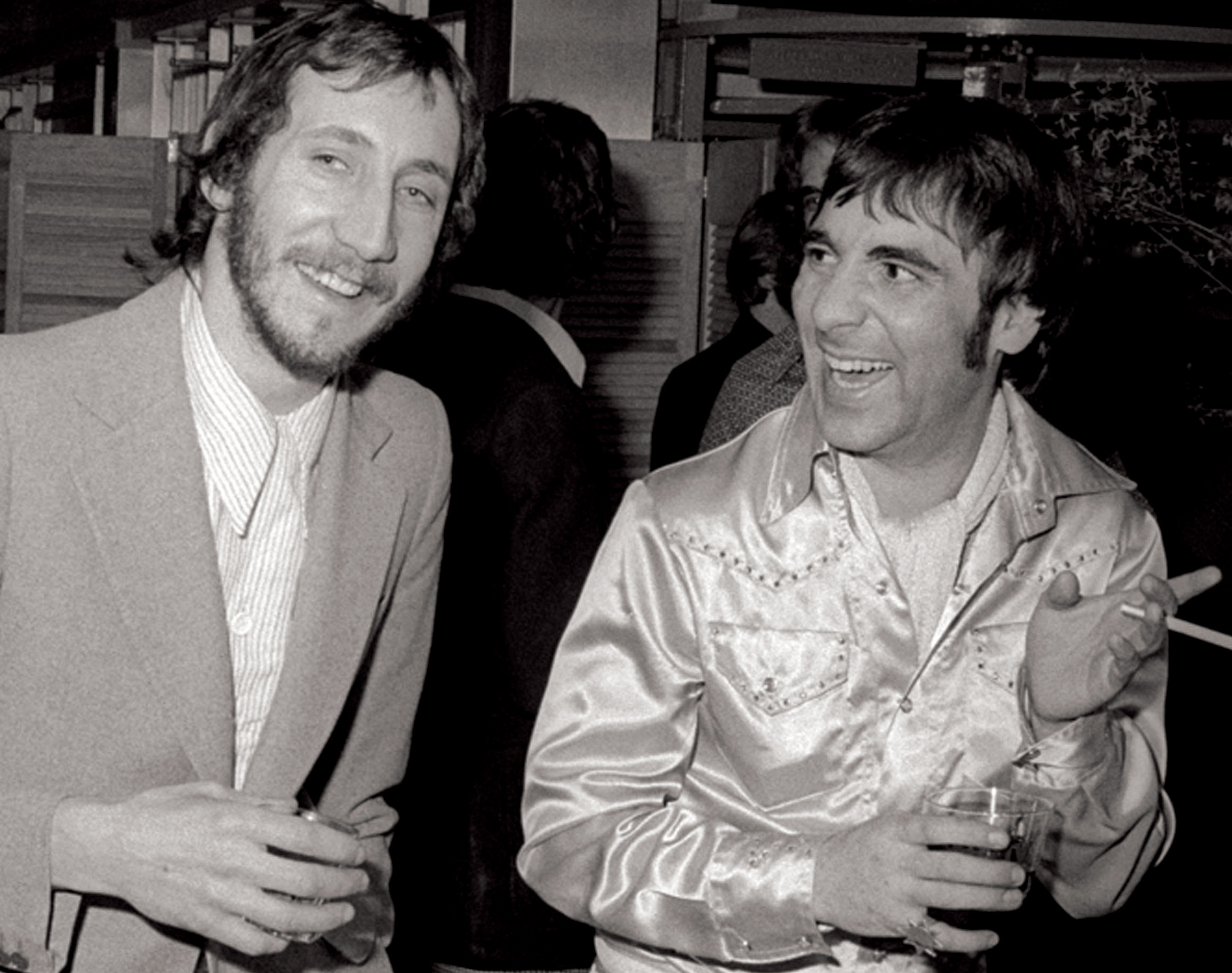

“The press tried to paint some kind of picture about how both bands hated each other’s guts, but of course it wasn’t true. In actual fact it was the complete opposite and when both bands did meet up we all got on like a house on fire. Pete Townshend used to ring me up and ask me to play drums on some of his demos. At the time he was living in a little house in Twickenham and he had his equipment set up in a small room upstairs. There was a fireplace in the room and I used to put the bass drum in the fireplace so that the sound would go up the chimney and help keep the boom noise down a bit.

“On the whole both members of both bands did quite a lot together. I even used to do some of The Who’s sound checks for them when Keith wasn’t there, for some reason or another. I used to sit behind Keith’s kit and think, ‘My god, what are all these drums for?’

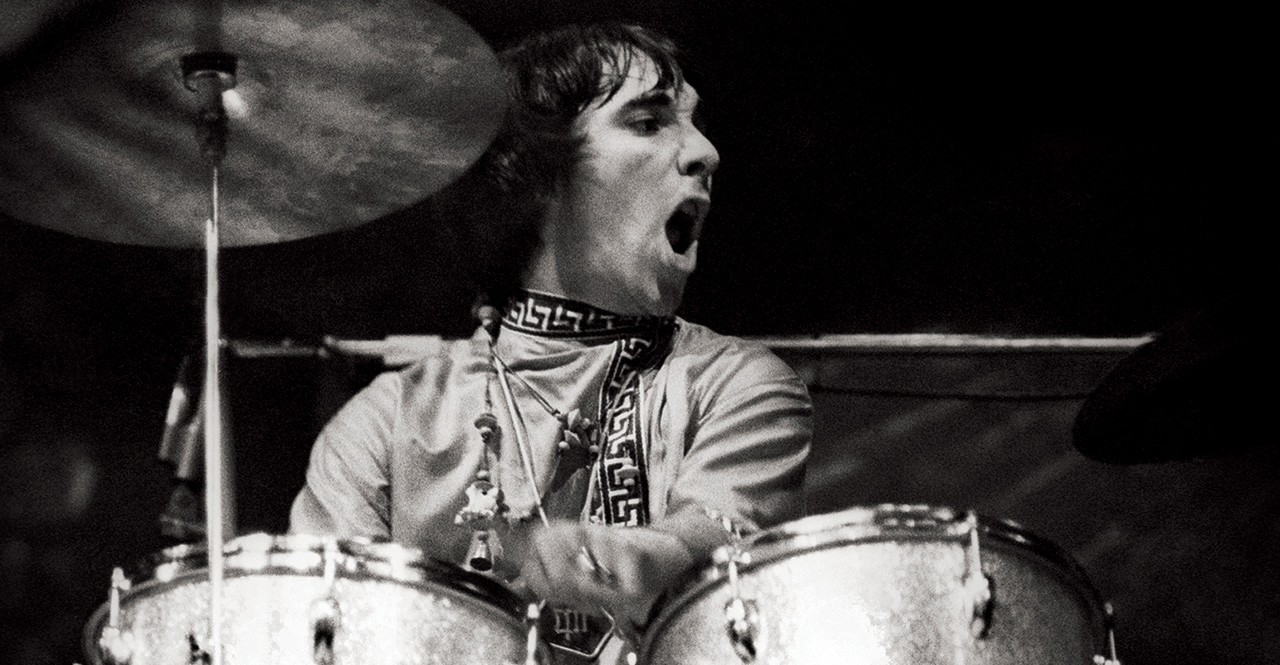

“I became very familiar with Keith’s drum kits over the years. It was unusual because he never really used a hi-hat. I mean hi-hats are quite an integral part of a drum kit in helping to keep a beat. I think a hi-hat restricted Keith. I think he felt trapped by it and if it was included in the set-up he would have to play a certain way, but if it wasn’t there he could be more expressive.

“Later on, once I got to play with The Who and I was learning the songs I tried to put myself in Keith’s shoes; but it was just impossible. He would put drum fills in places where they shouldn’t go.

“Pete Townshend sums Keith up the best way when he says that Keith had a built-in metronome and although he could go in and out of the song or the timing, Keith would still be there playing in time and still come in at the right moments.

“When you watched Keith, you couldn’t help but be mesmerised by him. Sometimes I used to sit right behind or beside him on the stage and watch him. He would do the same with me. We appreciated each other in that way. But many times I would see him do something and think, ‘How did he do that?’

“I don’t know if Keith thought that he was one of the great drummers but I feel that he was proud to be the drummer that he was. He was so great to watch and he did get a lot of praise and he was so completely different to anyone else on the scene. I have always said, ‘There is only one drummer that’s right for The Who and that is Keith Moon,’ and for me that is as simple as it gets.”

The Bandmate

By Pete Townshend

The Who

“An image of Keith comes to mind of the way he was often deeply reflective. Sitting opposite him at a table one would watch him take a wooden toothpick and pick absentmindedly and without reason at his front teeth. He always kept his mouth closed when he did this. His almost black eyes would look into the distance, and his mouth would pout, and then in one of his most characteristic mannerisms he would swing the pout to one side as though he was using it as rudder. It would be a signal. The faraway look would disappear and he would return to the room and in the early days come up with some joke or second-hand story that he thought would amuse. In later days it might be the signal for him to demand money, without saying why, and generally I gave it to him.

“In the very early days I suppose I was a little enamoured of him. Not sexually; he was a rather lumpy fellow physically, and any homoerotic feelings I had were towards the more conventional handsome men of the day like Chris Stamp, our manager, or – as is now well known – Mick Jagger. But he was like Kit Lambert who was equally eccentric and prone to move in an instant from reverie to outbursts of humour, and was easy to love. Despite the liberalisation of the sixties it was rare to hear men speak to each other of love at any level. Today, men are tough enough and easy enough to tell each other if there is a bond.

“I think it’s fairly safe to say that Keith was the first man to ever say he loved me, in his last days sadly, but I believed him, and I think he might have been the first man I was able to sincerely tell I felt the same way. And so when I think of him it is not as a drummer, or a crazy man who indulged in stunts, but as someone whom I admired, whom I enjoyed being with, whose small foibles all seemed attractive and engaging to me. He was, above all things, very funny, with a great memory for gags and finding ways to bring them into everyday conversation. But he was also earnest and imaginative, and it was very rare that I bored of being in his company.

“I think the word I would use to describe Keith’s style of drumming is ‘free’ rather than ‘anarchic’. He knew no boundaries. It does surprise me that there is still so much interest in Keith as a drummer because very few of our musician peers seemed to appreciate Keith’s style. Ronnie Lane – for example – adored Keith but I think he thought his drumming had a deleterious effect on my songs. But Buddy Rich liked Keith’s playing, and so did other jazz drummers I met, like Tony Williams. These two guys alone must provide a testament, really the top two jazz drummers of the sixties.

“The jazz-trained Charlie Watts also loved Keith’s fluid style. I think Keith’s biggest fan was John Bonham who always watched Keith intently when he could (sitting in for the entire recording of Won’t Get Fooled Again).

“The loon stuff was a big part of Keith’s world. His stunts created a constant flow of PR for The Who, otherwise we might have discouraged him. They were mostly very funny, but not always. I often felt sorry for Keith when he was in his most ostentatious mode, off stage. It was almost as though he felt his stage work was not enough; that he had to keep performing.”

The Roadie

By Richard Cole

“Being a roadie for The Who meant doing a bit of everything really. I did a lot of driving of the van, with Keith, carrying his drums around. It was often me, Keith and John [Entwistle] in the van. They lived quite close to me so that meant I could pick them up. Roger [Daltrey] had his own car so would drive himself and Pete would sometimes drive himself or catch the train. My first job meant going to Edinburgh with them. In the early days we all stayed in the same hotels and spent a lot of time together and Keith wasn’t much more different to what people wrote about him. I remember that on that trip to Scotland Keith asked me to stop the van because he wanted to go into a hardware store to get something. As he ran inside I asked John what he was after and John just smiled. Keith returned with weed killer and sugar. He used them to make smoke bombs. Even back in those days he was always up to tricks. John was always very quiet but he was like Keith’s silent accomplice.

“As a drummer there was nothing else like Keith Moon; he played furiously. He was unusual in so many ways. Just not using the hi-hat is one example. He used all of his drums all of the time. Another unusual thing was that The Who were only a three-piece band. This was unusual because most bands from that era were at least a four piece that included a rhythm guitarist. They moved around on stage a lot; apart from John, he never moved, he was like a statue. Then [Pete] Townshend would be smashing his guitar into the amps and Daltrey would be swinging his mic around. There were no barriers in those days and the audience were very close to the band. People had to be careful not to get hit.

“I saw some of the smashing up of the gear but it didn’t happen every night. One night in Bishops Stortford I remember he smashed the whole kit up; even the cymbals got broke. We had no replacement drums. Luckily I played drums and had a blue Premier kit (at the time Keith played a red kit). But Keith had to buy my kit from me; I wasn’t going to let him smash my kit up.”

The Contemporary

By Mick Avory

The Kinks

“It was once I was drumming with The Kinks and we were touring, doing the package tours and club circuit, that I got to know The Who. I saw Keith when he was in The High Numbers. I thought he was a mad drummer and he didn’t go unnoticed. Keith didn’t impress me with his technique, but his flair of how he played the music did. He also looked good when he played because of his flailing arms.

“Keith played very differently to me. I played more organised patterns but Keith didn’t. He was a lot more free and did some amazing rolls and flicked his sticks all over the place. Keith didn’t want to be disciplined, he wanted to be free. Keith was a natural showman.

“I don’t think Keith needed drummers’ rules in his life. I doubt he would have understood them. I’m sure he had patterns in his head, but I doubt they were formed the way usual drummers do; using bars and embellishments. He just wasn’t that organised.

“When I didn’t see Keith on the road I would see him down the various clubs in London. I’m sure he did have a sensible side but he didn’t show it very often. I think he felt that he had to live up to his reputation. I think he had to do stupid things because he felt people expected it from him. I saw Keith do some stupid things in the Speakeasy but the management never threw him out; if anything they expected this behaviour. If Keith had lived on to be my age now he wouldn’t still be doing it; he wouldn’t be able to.

“It didn’t surprise me when I heard about Keith’s death. He was never going to make old bones. Keith was of a time when lots of people took lots of things and they weren’t that cautious about it. That’s the way life was and that’s the way Keith was; and he played drums that way too. Keith got all the success and notoriety but it burned him out.”

Keith Moon: A Tribute Compiled by Ian Snowball & The Estate of Keith Moon is out now, published by Omnibus Press and available at all good retailers (www.omnibuspress.com).

What Really Happened the Night Keith Moon Died?