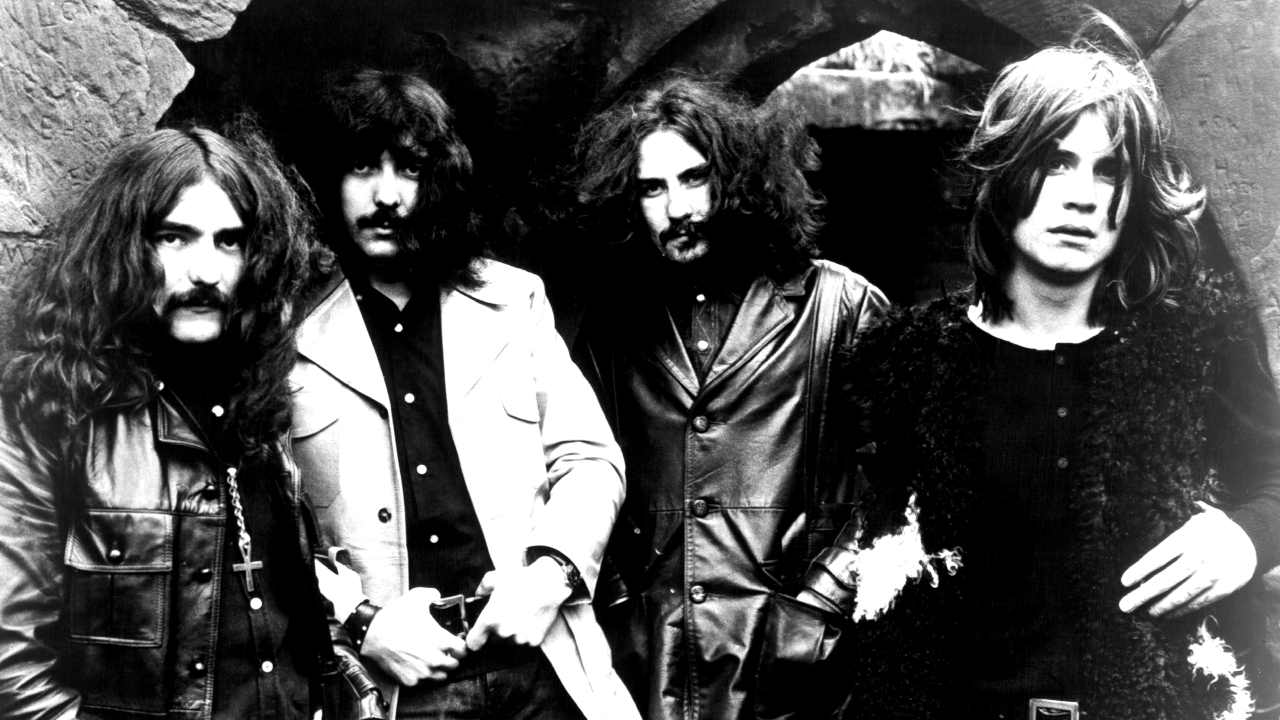

“If it hadn’t been for music, I’d have ended up killing myself”: the epic life and turbulent times of Black Sabbath’s Geezer Butler

An epic career-spanning interview with Black Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The accent has hardly changed in over 70 years. He may have made his home in Utah, where he lives with Gloria, his American wife of 43 years, but nothing has ever taken the working-class Brummie out of Geezer Butler. His roots remain obviously preserved in his doleful speaking voice. The downbeat, sing-song cadences that make him sound as if in a continual state of surprise. His every sentence ending like the punchline to a self-deprecating joke.

These days, Butler mournfully intones, he is not doing so very much of anything. As he describes it, generally he wakes up each morning with three cups of tea. Yorkshire Gold, always. He has his two dogs to walk. He lost his eldest dog just the other day. The Butlers have three cats, too. All are rescue animals. The man who shared a stage with notorious bat-biter and chicken-slayer Ozzy Osbourne is an inveterate animal lover and animal rights activist, a campaigner for PETA and the Humane Society of the United States. Otherwise, he passes his time reading books, non-fiction history mostly, and watching his beloved Aston Villa on the telly. Seventy-four in July, he bemoans the fact he’s starting to feel his age.

“In just the last four weeks I’ve developed tinnitus in my ear,” he offers matter-of-factly. “Driving me bloody mad. And I’m deaf in the other ear, too.”

Article continues belowIf Butler could help it, he wouldn’t be interrupting his routine with doing an interview today but needs must. He has a book to promote. His memoir, Into the Void is, like its author, altogether no-nonsense and often laugh-out-loud funny. The greater part of it, of course, is taken up with his long and erratic tenure as bassist with Black Sabbath. A role he writes of as ‘like being an actor in a soap opera.’

It’s been six years now since Butler, Osbourne, and Tony Iommi pulled down the final curtain on the Sabs’ saga. There will, Butler insists, be no turning back from this end to their gloriously bonkers road.

“Rock legends? That’s all very silly,” he says. “If I thought of myself like that, I’d start dyeing my hair again and doing me shopping in black leather.”

He was born Terence Michael Joseph Butler in Aston, Birmingham on July 17, 1949, the youngest of seven children, six boys and a girl. His father James, an engineer, and mother Mary Butler, a housewife, were devout Irish Catholics transplanted to Birmingham from Dublin. Both parents were God-fearing and teetotal. The family crammed into a three-bedroomed terraced house: the three middle boys in one bedroom, mum and sister in another, his dad and him sharing the box room at the back of the house. His two eldest brothers were away serving in the Army.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Like countless others of his generation, music arrived with Terence Butler in the mop-topped form of The Beatles. He was there on the frigid Thursday night of December 9, 1965 when the Fab Four played at Birmingham Odeon, but couldn’t hear them above the screams of a couple of thousand Brummie schoolgirls. He started off doing Beatles and Stones covers in a grammar school band, The Runes. Next there was the showier Rare Breed, who performed in Halloween face paint and used flour instead of dry ice for their wannabe elaborate stage shows at the second city’s pubs and clubs.

Back then, Butler was on rhythm guitar, a “beautiful red Hofner Colorama”. He switched over to bass after seeing Cream at Birmingham club Mothers, and finding himself mesmerised by their bassist Jack Bruce. Rare Breed brought in a new singer, a local tearaway who’d posted up a small ad at the Jones & Crossland musical instrument shop: “Ozzy Zig needs a gig. Singer with his own PA.”

Soon enough, Butler and John Osbourne, as was, were out of Rare Breed and into the Polka Tulk Blues Band. There they played alongside guitarist Tony Iommi, a year older than them and the bully at Osbourne’s Prince Albert School, and Iommi’s drummer pal, sweet-natured innocent Bill Ward.

Together the four of them pressed on and formed yet another hard-blues combo, Earth. Butler was training to be an accountant at this point. His day job didn’t survive Earth securing a residency at the Star-Club in Hamburg in the summer of 1969, the very same place the nascent Beatles had once worked. They were booked to do seven 45-minute sets a day. They used the engagement to hone songs Butler was beginning to put lyrics to over Iommi’s industrial-strength riffing. Returning home, they ditched Earth as the band’s name for something more befitting these new songs, each one as pregnant with doom and menace as the next. Although when they first stepped out as Black Sabbath it was as the Saturday night entertainment at the Banklands Youth Club in Workington on August 30, 1969.

What’s your first or strongest memory of your childhood?

I was tiny, and a sphere appeared to me when I was in bed one night. It was spinning in front of my eyes, and I could see all these things happening inside it. There was a guy on stage. The only stage I’d seen to this point was at school for the Nativity play. He had long blond hair, and silver boots on. He was playing an instrument; we didn’t have a TV set, so I didn’t know what a guitar looked like. It half freaked me out. I’d heard so much about banshees already in my childhood, and I thought that’s what it was. When I told my parents about it they said I’d had a nightmare. It wasn’t, it was real. It was like a dream, but I was awake.

It sounds like yours would have been a noisy, chaotic house?

It wasn’t too bad because everybody else was at work most of the time. As soon as my brothers came home, they’d have their dinner and then piss off out to the pub. My dad’s dad was an alcoholic and would beat the hell out of him. He left home when he was fifteen. I came home one day with a can of shandy and he went mental at me. Told me I was going to grow up to be an alcoholic. He wasn’t far wrong.

What characteristics do you think you inherited from your parents?

Inquisitiveness. I’m very curious. I like to learn about history, and geography. My love of animals, too. We always had animals in the house. I got my first dog when I was seven. I used to play football with him out in the yard. Because there were seven of us, I would get the tiniest bit of leftover meat for dinner. It was usually burnt to a crisp. One night, it happened to be under-cooked. I cut it open and blood came out. That was 1957, and I’ve never touched meat since.

I didn’t even hear the word ‘vegetarian’ until 1969. We were doing the Star-Club, and went to this Chinese restaurant across the road. Everybody else was having chicken and rice, and I asked the waiter to bring me just the rice. He said: “Ah, you’re a vegetarian.” Before that I never had any money to go out to restaurants or cafes. All we’d do different is go to the chippy. I found out later that the chips were fried in the same oil as the fish, so I don’t eat chips now.

What else did being born into an Irish-Catholic family instil in you?

Number one: religion. My mum and dad were very, very strict Catholics. I’d never even dream of missing mass or benediction, or confession. The house was filled with pictures of Jesus and Mary, and crosses. My dad used to go to bed at half past seven every night. He’d always say his prayers before he got into bed. Because we shared a room, I’d have to kneel beside him by my bed. I became a religious maniac. Every bit of pocket money I got, I’d spend it on rosaries, crucifixes and prayer books. I loved learning Latin…

Yet you lapsed in your late teens. Why?

It was when I started growing my hair. There was one nun who would take the piss out of me every time I went to mass. I’d always be late, and there’d be nowhere left to sit. She’d make a beeline for me and say: “Hello, miss, do you need a seat?” Then she’d ask a man to stand up and let the little girl in. One day, I turned around, gave her the V sign, and never went back.

When was the first time you picked up and played an instrument?

I was at grammar school. There was a kid who brought in an acoustic guitar. It only had two strings on it, and he asked if anyone wanted to buy it. He wanted ten bob in old money, which is about fifty pence. My brother gave me the money. When The Beatles came along I learned to play the melody lines from their songs. I couldn’t play chords because there weren’t enough strings.

Eventually another brother gave me eight pounds to go and buy myself a proper guitar. I also bought a copy of Burt Weedon’s Play In A Day book and started to work out all the chords. Seeing The Beatles was the greatest day of my life up to then. One of the Moody Blues used to live up the road from me. We’d walk past his house and hear him rehearsing. Then I saw Cream at Mothers. I couldn’t believe what Jack Bruce was doing, playing bass, and filling in all the rhythm parts. That’s what I fixated on.

It sounds like Rare Breed would have been an interesting band to see.

It was. We were so nuts we’d never get booked at the same place twice. Eventually we had to change our name to The Future just so we could get gigs. There was this one place that had white, council-issue towels in the toilets. I’d got all this make-up on my face, and I used one of these towels to wipe it off. The manager went mental at us. He didn’t care about the music, only that I’d ruined one of his towels. If it hadn’t been for music, I’d have ended up killing myself, or else washing cars for a living. I couldn’t see any other future for myself but for playing music.

What were your first impressions of the lad who wrote the ad: “Ozzy Zig needs a gig”?

That he was a complete nutter. When he first came to our house, one of my brothers answered the knock at the door. My brother came into the front room and told me: “There’s something for you at the door.” When I asked him what he meant by ‘something’, he said: “You’ll see.” I opened the door, and there was Ozzy. He had a haircut that was only a bit longer than a skinhead. He was wearing his dad’s toolmaker’s work gown. He had a chimney sweep’s brush over his shoulder, no shoes on his feet, but he was holding one shoe on a dog lead. It was pissing down with rain, too. I just burst out laughing at him. Then I found out he’d just got out of nick. He’d been sent down to Winson Green prison on a burglary charge. Like I said, a nutcase.

In your book, you write of learning that Ozzy “could defecate at will’. How exactly did you establish this fact?

Our first gig with Ozzy singing for Rare Breed was at Aston University. We were so bad, the bloke who’d booked the night refused to pay us. He may have eventually given us a couple of quid. But as we were leaving, we saw his Jag was parked outside the front door. Ozzy climbed up onto it and did a great big turd on the bonnet, at will, and then we scarpered.

The way you write about the young Tony Iommi in the book, he sounds terrifying.

He was in those days. Tony never shied away from a fight, that’s for sure. If somebody ever got out of line, he’d let them know about it. It was necessary. You had these four loonies from Aston, and we needed a leader. We all looked up to Tony. He’s one of those people who happen to have a presence about them. He commands respect. Whatever he wanted to do, that’s what we did. I’d seen him in a couple of fights, and I wasn’t about to get on the wrong side of him. If you talk to Tony, he’s okay. He’s probably my best friend now from the band. We’re still in touch and see each other occasionally.

Whereas poor Bill Ward comes across as one of life’s eternal victims.

Bill is easy-going. Everybody that meets Bill gets the impression that he’s a lovely, kind bloke. And that’s the way he is. He never has a bad word to say about anyone. He’s a gentle man. And so, because the three of us were all hooligans, Bill was the natural one to take the piss out of all the time. Bill would take it, and he’d even like it occasionally. To me, it’s always seemed weird that four guys who literally lived round the corner from each other all liked the same kind of music and were available just at the right time. It was like it was supposed to be, almost fictional, really.

In October 1969, the four members of Black Sabbath went into Regent Sound studio in London with Rodger Bain, a staff producer at their new record label Vertigo. They spent just two days making their debut album. The first day to record its seven songs live to tape, the second to have them mixed. Time enough for them to have changed the world at a stroke. Critically, the Black Sabbath album was either reviled or shunned, but it went on to spend a year on the Billboard Hot 200 in the US. More significantly, from the ominous drone of its title track on, in just 38 minutes and eight seconds Black Sabbath had famously, and single-handedly, invented heavy metal.

Seven months later, they were back with Bain at Regent Sound recording the follow-up, Paranoid. This one took all of five days to complete. Being short of a three-minute song to bring the record up to the minimum running time for it to be designated an album, Iommi conjured the riff for the track Paranoid while the rest of them were on a lunch break. Butler’s lyrics describe the then-undiagnosed depression he’d been plagued with for years. A four-million seller in America, Paranoid made Black Sabbath unlikely superstars.

Black Sabbath were the product of your environment in Birmingham, weren’t they? It sounds like heavy industrial machinery.

Across the road from our house was the Cyclo Gear factory and a lorry repair shop. You’d hear the clanging all day long. Tony worked in a factory. Ozzy was in the slaughterhouse. Bill was a truck driver’s mate. The music reflected our working-class background. I wanted the lyrics to reflect that too. Life wasn’t lovey-dovey and all that kind of crap. The Black Sabbath album was recorded just as we’d do a gig, the four of us playing along together. The first time I heard it as a piece was at home on our Dansette record player. I thought it was good.

What’s your instant recall of making Paranoid?

God. It was 1970. I remember us going to Wales first with Rodger Bain, because he wanted to hear the songs. We were living in at Rockfield Studios, which was just a rehearsal place on a farm. We set up in this old barn. When we started up War Pigs, the whole roof fell in because of the volume. I wrote down the lyrics to Paranoid quickly, and I already had the title. Ozzy went: “What the fuck does ‘paranoid’ mean?” I told him: “You know when you’re smoking dope, and you think something bad is going to happen? It’s that.”

In your book, you write very candidly about your struggle with depression – how growing up you self-harmed and contemplated suicide. In 1970, who could you have possibly turned to for help?

There was no one, or nowhere to turn to. I went to the doctor about it, and he literally told me to go and have a couple of pints, or take the dog for a walk, and I’d be alright. Nobody ever talked about anything like depression back then. Whenever I was having the blackness, the others just used to think I was in a mood. They’d go: “Ah, come on you moody git, what’s the matter with you?”

I wasn’t properly diagnosed until 1990. I went to this place in St. Louis on the verge of a breakdown. I couldn’t figure out what the hell was going on with me. I explained it to this doctor there and he told me I was horrendously depressed. He put me on Prozac – it had just then come out – and I went on these pills for six weeks. At first I didn’t think they were working, but by six weeks I was starting to feel a kind of happiness I hadn’t felt for ages. I’ve been on different medications ever since. Not all the time. Occasionally, I can feel the start of something coming on and I’ll have a couple of pills.

Paranoid was a top-five hit single in the UK. You performed it on an edition of Top Of The Pops presented by Jimmy Savile.

He came over to us when we were on the show and said: “I see your single’s pissing up the charts.” That took me by surprise, coming from a BBC DJ. I’d read this one article about him in the News Of The World, or the People. It was hushed up by the next week. But obviously, even then somebody, somewhere, knew what he was up to. I just thought he was a bit of a weirdo.

From there to Sabbath playing the California Jam to an audience of 200,000 in April 1974 was less than four years. How was it to be going so fast?

It was just non-stop. We did tour after tour, and then we’d come home and have an album to do right away. We never had time to think. By the time we got to the California Jam, we were so coked out of our brains we didn’t think too much about it. We didn’t even know we’d been booked to play the show. One of our roadies called to tell us about it the week before.

What for you personally was the greatest high point of that whole period?

When the Paranoid album went to Number One. We were in Belgium, it had not long come out, and our tour manager came up to us and said: “Guess what?” The happiest I felt was when we did the Sabbath Bloody Sabbath album in 1973. We all had money, we were doing sold-out tours, we’d established ourselves all over the world. Everything was going great, and we loved writing that album. We wanted to advance ourselves musically. We had a great time making the record, too. And then it all fell apart.

What was the most Ozzy-like thing you were witness to Ozzy doing?

It was in a plush hotel in Munich. We were standing around in the lobby, and a coachload of American tourists were checking in at the same time. We’d been out for dinner, and Ozzy announced he was desperate for the toilet. I watched him go off and get in the lift. He thought the lift would be going up to his floor and he was already dropping his trousers, because he couldn’t wait. Then the lift went down to the basement instead. By then, the Americans had all come over to wait for it with us. When it came back up and the doors opened, there was Ozzy – crouched down, trousers round his ankles, and a great big turd underneath him. I was screaming with laughter. The Americans were all stood there with their mouths hanging open, staring in astonishment. It was like something out of Fawlty Towers, only worse.

You said that after making Sabbath Bloody Sabbath it all fell apart. What went wrong?

Relentlessly, we kept asking our manager at the time to see our accounts. We knew we were earning more than we were being told. Of course, we never did get hold of the accounts, so we decided to get rid of him. That was a lot easier said than done. Lawyers and solicitors got involved. We started doing the Sabotage album, but there were all these court actions going on. We’d be in the studio recording, and people would turn up to serve us with subpoenas and writs. Every day. It took us ten months to do the album because of all the business stuff. We didn’t have a clue what was going on. And that was the beginning of the end for that line-up of the band. We had to pay the manager off – a million dollars from the advances for our future albums. So we weren’t going to be earning any money from them. It was all just too much. It killed us.

Sabbath’s course would never again run smoothly. There was a second, all too brief, golden era when the big-voiced Ronnie James Dio took over from the ousted Osbourne. That line-up made two fine albums: 1980’s Heaven And Hell and the following year’s ever-underrated Mob Rules. Then, and for the next 16 years, even Black Sabbath appeared to stop taking Black Sabbath seriously. How else to explain the flirtation with Ian Gillan as their singer, never mind the one with David Donato.

The original line-up reunited in 1997, but their legend was burnished. In his book, Butler writes about the whole of his Sabbath experience with a vaguely bemused air, as if still not quite sure how, or why, any of it happened. He is, though, sharply pointed about the process of making what will surely remain the last Sabbath album, 2013’s 13, with Brad Wilk from Rage Against The Machine having replaced the ailing Bill Ward and Rick Rubin producing. “He didn’t do a lot,” is Butler’s summation of Rubin.

He writes sweetly of first sighting his future wife Gloria, at St. Louis airport on the Never Say Die tour in 1978. He had his limo driver tail her red Porsche from the airport, and at a stop light asked her out to dinner. He left his first wife and childhood sweetheart, Georgina, for Gloria, and they have now been married for 43 years.

Have you always acted as impulsively as you did with Gloria?

Not really. I was married at the time, but when I saw Gloria at the airport, magic happened. I knew instantly I had to meet her and get to know her.

What sustains a rock-and-roll marriage over such a long period?

Especially when we were on tour with the band, you spend time apart from each other, and so it doesn’t get stale. I’ve never tried to cheat on or been unfaithful to Gloria. That helps a lot! Having kids together, that’s a whole other thing. I think the main thing is we just haven’t taken each other for granted. Of course, we have our arguments now and again. And I’m still surprised she stayed with me when I was getting drunk all the time. But we got through it, and we’re just as happily married now as ever.

What was the first thing you heard Ronnie Dio sing with Sabbath?

We’d the music written for Children Of The Sea, but Ozzy hadn’t been able to come up with any vocals. We knew it was going to be a good song. We played it for Ronnie, and he came right out with the vocal. It was incredible. We knew then he was the right person. Don Arden was managing us at the time. The News Of The World had also done a whole thing about Don being a gangster. So we knew of his reputation. He went mental when Ozzy got sacked. He told us he was taking on the original Sabbath, or nothing. When Ronnie came in, Don said “You can’t have a bloody midget replace Ozzy!” This was in front of Ronnie. That’s the way Don spoke. There were no airs or graces about him, to be sure. He told us: “Either get Ozzy back, or I’ll go and manage him instead.” That was the end of Don.

You write how Tony set Bill on fire during the making of Heaven Of Hell. Why on earth would he have done that?

Bill kept growing these big, long beards. Whenever his beard got to be a certain length, Tony would set fire to it. It just became a joke thing in the band.

It was when we were mixing Heaven And Hell in London. I don’t know what Tony was on, but it was something. Bill’s brother had turned up to collect him from the studio, because Bill didn’t have a driver’s licence. Tony went: “Just before you go, Bill, can I set you on fire?” Bill told him to leave it out, and went off. Then about ten minutes later Bill came back into the room and said to Tony: “Alright, you can set me on fire.” Of course, having got Bill’s permission, Tony just went nuts. He doused him in this flammable cleaner that was used to wipe off the mixing desk. Bill went up like a bloody bonfire. He was rolling around on the floor, trying to put the flames out. There was nothing in the studio but old newspapers. We threw those on him, trying to stop the fire, but obviously that just made it worse. Eventually, his brother came in and threw water all over Bill. But by that time Bill’s socks and his jeans had melted into his legs. He was very badly burnt. His brother took him straight to the hospital. Bill was told they might have to amputate one of his legs. We are all sad about it, of course we were.

At three a.m. the next morning, Bill’s mum called me at home. She was shouting down the phone. I told her it hadn’t been me, but I couldn’t tell her Tony had done it. Eventually she figured out for herself it was Tony, and went raving round to Tony’s mum’s house. Poor old Bill. Believe it or not, he took it in good spirits.

How does something as well-matched as the Heaven And Hell-era Sabbath line-up go so badly wrong so quickly?

Because you don’t really get to know someone until you go on tour with them. It’s great seeing someone occasionally, having dinner and that kind of thing. In fact, with Heaven And Hell, both the album and the tour were brilliant. It was our biggest record since Sabotage. But Ronnie got the idea it was down to him, and that he’d revived Sabbath – and he wasn’t short of telling us about it. He started to moan to me about Tony playing too loud, and how long his solos were. I used to say to him: “Well go and talk to Tony about it, don’t tell me.” In the end I got sick of being in the middle of the two of them. Then one day Ronnie came in and said to Tony and me: “If I’m going to be singing old Sabbath songs, I want to get part of the royalties for them.” Tony and I told him no way. That was the end of it.

What for you was the lowest point of the time you were in Sabbath?

Almost that whole period of sixteen years was just chaotic. When Ian Gillan came in, I thought it would be a good time to make it a different band – an Iommi-Gillan-Butler-Ward album, or something like that. But Don Arden was back managing us, and he got us a great record deal with Warner Brothers, only it was based on it being billed as Black Sabbath. After Gillan left to rejoin Purple, I stayed on with Tony in LA, auditioning all these singers, but it was becoming a joke.

Then my son was born with transposition of the great arteries. Music didn’t mean anything to me at that point. I just wanted to go and be with my son and wife. It was fifty-fifty whether our boy would live. A terrible time in my life.

Did the original line-up get back together in 1997 older but also wiser?

Yes. I mean, Ozzy had established himself and he was full of confidence. He’d lost a lot of his confidence by the late seventies. Now he was bigger than Sabbath. We all had our problems sorted out, and it felt fresh again.

How, in a word, would you describe working with Rick Rubin?

Perplexing. I still don’t know what he did. He certainly didn’t do anything with Tony and me. Maybe he was great with Ozzy. Tony nearly murdered him. Especially when he told Tony he needed to get a 1968 amp so he would sound like he did on the first album. I was left thinking how the hell this guy had got his reputation. But the record company loved it, and everybody else thought if Rick Rubin was producing, it must be brilliant. They all swallowed the hype.

When were you, Ozzy, Tony, and Bill all last together in the same room?

In 2012, I think. I haven’t spoken to Ozzy since the last gig. Sharon Osbourne and Gloria fell out and that was it. We’re not allowed to speak to each other by command of our wives. I’ve seen Tony a couple of times. We got given a lifetime Grammy in 2019, and that was the last time I saw Bill.

“These days I’m just glad to be happy and enjoying life. I’m still in mourning for my dog who passed last week. Dogs have always been my best mates. I prefer to stay in at home with my animals over socialising with other people, to be honest. Animals don’t give you the bloody problems that humans do.

And so, what’s next?

I don’t know. I’ll probably die.

Into The Void by Geezer Butler is out now

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.