"People found out we weren't The Beatles and that came back to haunt us": The curious case of the band whose career was derailed by a rumour

They were The Beatles – or so a million record buyers thought in 1977

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It was one of Capitol Records’ most mysterious releases. The record, cryptically titled 3:47 EST in Canada, but just bearing the band’s name for international distribution, carried no information about the group, no photos, no songwriting credits. The band were called Klaatu. But, for a time, rumour had it that they were another, far more famous, band entirely…

Released in August 1976, the Klaatu album earned several enthusiastic reviews. Canada’s Record Month called it “a terrific concept album”, while Trouser Press said it was “an impressive sci-fi answer to Bowie”. But the reviews didn’t translate into sales, and it looked like Klaatu was headed straight to the bargain bin.

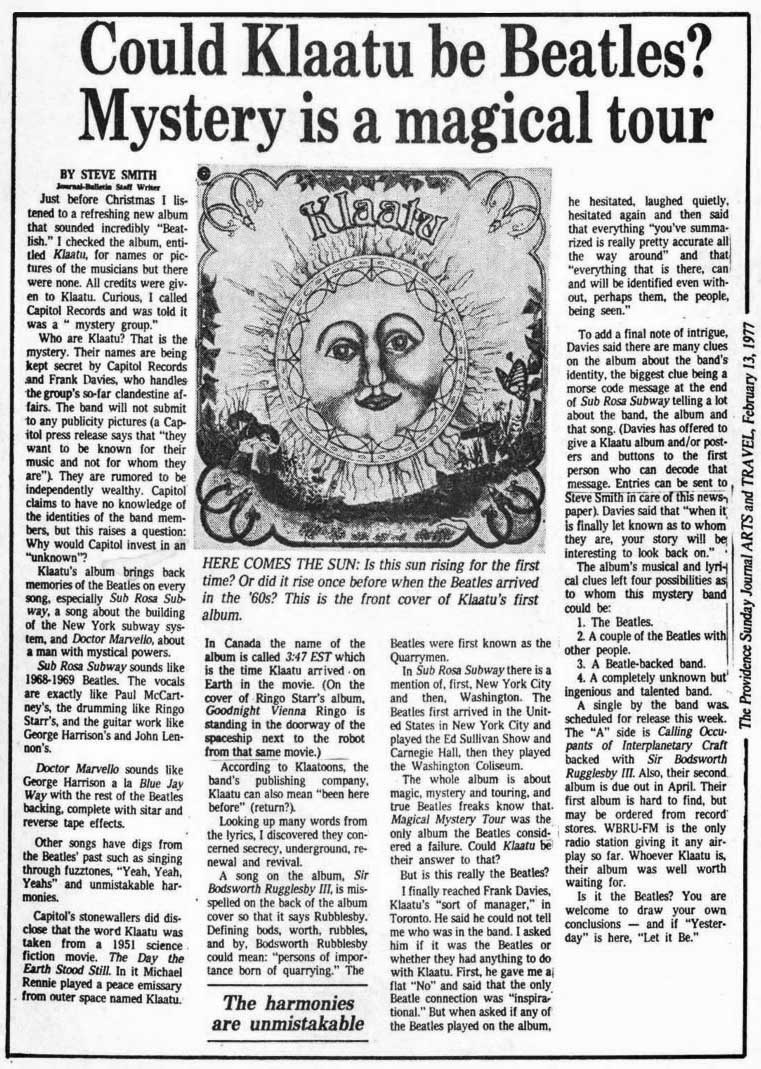

Then, on February 17, 1977, a feature headlined ‘Could Klaatu Be Beatles? Mystery Is A Magical Tour’, written by Steve Smith, a young journalist working for Rhode Island daily newspaper the Providence Journal, changed everything.

“We used to get a bunch of albums to review. If they weren’t reviewed they went in a pile, and if you wanted anything you grabbed it,” Smith tells Classic Rock. “I saw the Klaatu album, took it home and listened to it. It had Beatle-sounding stuff, so I started researching. And couldn’t get any answers.”

The main question Smith wanted an answer to was simply: why did the album sound so much like the Fab Four? “It struck me almost immediately,” he says. “The track Sub-Rosa Subway is completely Beatlish.”

In his 1977 review, Smith wrote that the song’s vocals are “exactly like Paul McCartney”, the drumming “like Ringo Starr’s” and “the guitar work like George Harrison’s and John Lennon’s”. Doctor Marvello, said Smith, sounded like Blue Jay Way-period George Harrison, “with the rest of The Beatles backing”. Other songs had “digs from The Beatles’ past, such as singing through fuzz effects, ‘Yeah, Yeah, Yeahs’ and unmistakable harmonies”.

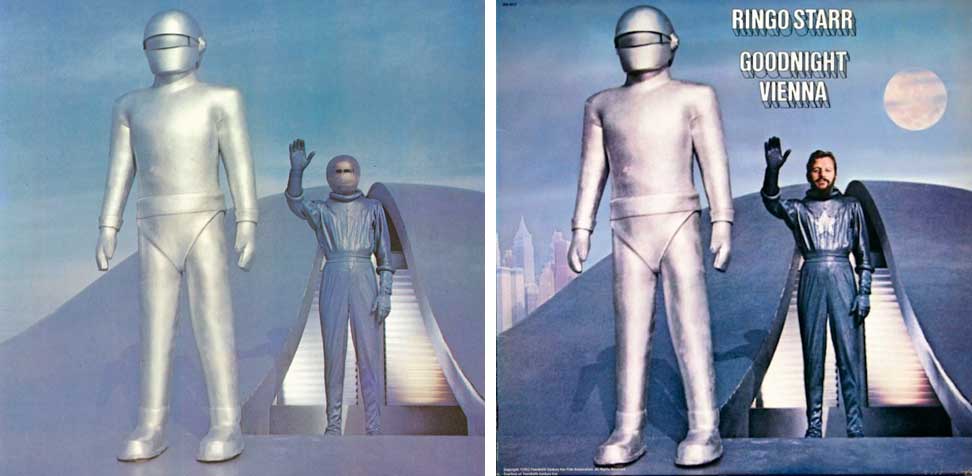

The sleeve of Ringo Starr’s 1974 solo album Goodnight Vienna had the drummer standing in the doorway of the spaceship from the 1951 film The Day The Earth Stood Still, next to the giant robot and dressed in the outfit that actor Michael Rennie wore as Klaatu, the alien peace emissary in the film. Smith wondered if the name of the band was a clue in itself.

Summing up (and hedging his bets), Smith concluded that this mystery band could be: 1. The Beatles. 2. A couple of The Beatles with other people. 3. A Beatles-backed band. 4. A completely unknown but ingenious and talented band.

Smith contacted Capitol Records for more information but got nothing. “Capitol told me they didn’t know anything. I didn’t believe them. You don’t just sign a band blind. They said they’d signed these guys through Frank Davies, who’d released them on Daffodil Records in Canada.”

“I’d recorded and produced two or three of the Daffodil artists at [Rush producer] Terry Brown’s studio in Toronto,” Davies says today. “He played me two or three of the Klaatu tracks and I told him he didn’t need to play me anything else, I wanted to sign them. My label was centred in Canada, and what I would do with my artists back then was go out and put together a US deal, or deals around the world. I played the tracks to Rupert Perry who was head of A&R at Capitol Records in the US. He loved them and said he’d like to sign the band.”

But Klaatu weren’t going to go down the tried and tested route. “The guys wanted to try a new approach,” says Davies. “They wouldn’t do photos, or interviews, or have a bio. I was cool with that. It was different. They weren’t going to play live, either.”

“We were three unknown guys from Toronto and didn’t want the focus to be on us as individuals,” says Klaatu vocalist/bassist/keyboard player John Woloschuk. “We really wanted the music to be the focal point. Also, we knew that the music we wanted to record couldn’t possibly be replicated on stage by three people.”

For his article, Steve Smith asked Frank Davies whether Klaatu were The Beatles. “No,” Davies replied. Smith then went through some of the ‘clues’ he’d, found and Davies told him vaguely that he’s “pretty accurate”.

“I was definitely playing coy!” Davies says today. “By this time the album had been out six months. We did have some great press on it, but it had only sold seven or eight thousand copies in the US. We’d reached a point where we thought the first album was over, and the band had already started working on the second, which was shaping up beautifully. Then Steve’s story was published and all hell broke loose sales-wise.”

Klaatu formed when John Woloschuk began working at English producer/engineer Terry Brown’s Toronto Sound Studio in September 1974. Brown heard and liked the demos Woloschuk had made with guitarist Dee Long and signed them to his production company.

Drummer Terry Draper joined in February 1975 and the trio began recording what became the Klaatu album in studio downtime. “Terry Brown was our engineer and co-producer,” says Draper. “The fourth member of the band. He made us sound fabulous. The album was recorded over three years. We all had regular jobs so we used to record in the evenings and late at night.”

With the full album recorded and ready to go, Frank Davies signed Klaatu to Capitol. “They didn’t know who we were,” Woloschuk confirms, adding: “They signed us on the strength of hearing the first album. It was Frank that swung that deal on those conditions. They must have believed in the music enough to take a chance.”

“Capitol never got to meet the band,” says Davies. “Rupert [Perry, A&R] went along with the conditions because he wanted the band. He said that he at least had to meet them and watch them sign the record agreement. I told him he didn’t have to because I’d warrant that they were signed to me, my label and my production company. ‘The lawyers will be involved – my lawyers, their lawyers. They’re signing to you, through me and that’s that.’

“It took a little while, particularly when we got to Capitol’s Business Affairs. It was one of those things where you needed to have the confidence with the music. Which I did. Island had previously put out a one-off single and I had other labels interested. I said: ‘If you don’t want them under these conditions, don’t sign them.’”

Capitol took the chance and started sending out Steve Smith’s review all over the world. The gamble of signing the band paid off, and the rumours generated by Smith’s article soon began to take on a life of their own.

“We were in England, recording,” remembers Terry Draper. “Somebody told us about The Beatles rumour, and we all had a good laugh and went back to work. When we returned to Canada, it went ridiculous. Cashbox, Billboard, all the magazines, everybody was talking about it. It went around the world via the United Press agency. We didn’t know what to do. Frank started having to field the calls.

“Everybody who was making money – including us – was quite delighted that we were selling records and people were talking about us. So, did we want to come out of the closet, squash the rumour and stop record sales? The whole anonymity thing was to have private lives, be a normal person, still make music and millions of dollars. That was the goal.”

As the story gathered momentum, more Fab Four-related clues began to emerge. “Everybody investigating the story found out I used to work for EMI Records in London, who The Beatles were signed to,” remembers Davies. “They then found out that Terry Brown had been an engineer at Olympic Studios in London, and they starting putting all these little pieces together, with Capitol ending up with the record.”

Meanwhile, AM and FM radio in Providence began to play tracks from the album and they interviewed Smith on air. Other stations caught on to the story, and within weeks Klaatu were being played all across the US. The band themselves were keeping out of the rumour mill and beavering away on their second album, Hope.

“At that point we didn’t know how much impact it was going to have on our career,” says Woloschuk. “It was a global thing. I’m not sure how many pressing plants Capitol had assigned to the [first] album but they had to go into emergency mode. They didn’t have enough copies to go round and missed a lot of sales. It turned into a monster that was beyond our power and control.”

“All sorts of press did interviews with Rupert Perry,” Davies continues. “They didn’t believe that Capitol didn’t know who the group was, which added to the situation. ‘This record label is sinking money into this band, so they must have met them. So there must be something behind this…’”

By now the ‘Klaatu – are they/aren’t they?’ rumours had reached The Beatles and their inner circle. Tony Bramwell was one of The Beatles’ childhood friends and had worked closely with them and manager Brian Epstein during the 60s.

“People started saying that Klaatu sounded Beatley, and Capitol would neither confirm nor deny it,” says Bramwell. “Capitol in America weren’t that bright at the time. They were being coy about it and hoping people would be taken in. I thought: ‘What the bollocks is all this about?’ I was working for Polydor Records in 1977 but still also doing promotions for the individual Beatles, so I knew what they were doing – and knew that Klaatu wasn’t them.”

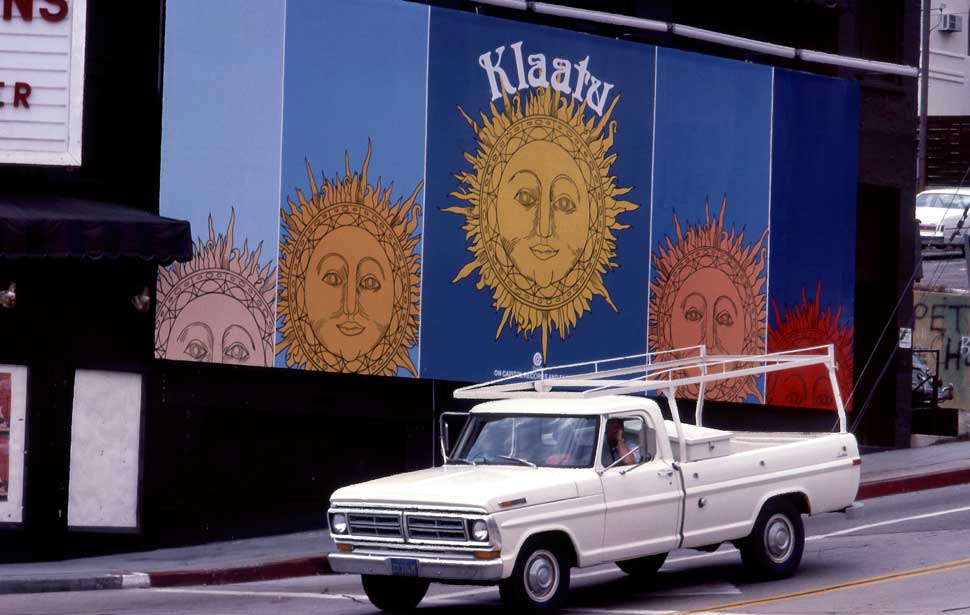

Frank Davies was originally from the UK and had worked for Parlophone in the 1960s. After the Klaatu story hit, he received a postcard from his former EMI colleague Paul McCartney, on which the ex-Beatle said he was “having a laugh watching all the rumours swirling”. Capitol continued to stoke the flames by placing an advert in the music trade magazines with a picture of the sun from the Klaatu album cover and the slogan ‘Klaatu is Klaatu’.

“It was a weak way of denying the rumour,” says Woloschuk. “There was never any intention of milking the rumour on our part. We were trying to hold on to our anonymity, though. We were young and idealistic and thought we could weather the storm. Which turned out to be incorrect.”

At the height of the media storm, Klaatu and Terry Brown were in the UK working on Hope, a cosmic-themed concept album that had its orchestral parts recorded over three afternoons at Olympic Studios with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Because of the ongoing sales of the Klaatu album, Capitol put back the release of Hope by several months. “We were delighted,” says Draper. “It gave us more time to finish it.”

Several months after the Klaatu story had broken worldwide, over at the Providence Journal Steve Smith had seen the light. He’d done some digging and had located an former girlfriend of one of the band. “She said: ‘If you’d contacted me a couple of months ago I’d have told you the truth! But now I think it’s funny.’”

Dwight Douglas, the Programme Director of WWDC-FM radio station in Washington DC, took a more academic approach to unmasking Klaatu. He visited the Library Of Congress and discovered that the songs from the album were copyrighted not to Lennon, McCartney, Harrison or Starkey, but to Draper, Long, Woloschuk and his then songwriting partner Dino Tome.

“When people found out we weren’t The Beatles, they thought we’d perpetrated the rumour and duped them,” recalls Terry Draper. “And that came back to haunt us.”

“The whole world resigned themselves that we weren’t The Beatles,” says Woloschuk. “Rolling Stone magazine gave us their ‘Hype Of The Year’ award!”

Released in September 1977, Hope was Klaatu’s most ambitious and mature work and went on to sell a respectable 400,000 copies. But despite this, the writing was clearly on the wall for the band.

“We got some great reviews on the Hope album,” says Frank Davies. “But for every great review, we’d get a newspaper article saying: ‘Hoax!’ or ‘Scam!’ and a lot of negative press. We’d release an album and it would go virtually unnoticed. We couldn’t get arrested, no matter what we did.”

Klaatu’s third album, Sir Army Suit, had cover drawings by artist Hugh Syme of a group of people that included the three Klaatu members, along with Frank Davies, Terry Brown and his wife and the Queen. “We buried ourselves among other people,” says Draper.

“Capitol were now asking us to do interviews, so our names became known to them,” adds Woloschuk. “With every successive album they wanted to open the door a little bit wider.”

Capitol picked up the option for a fourth album, on the condition that it was recorded in Los Angeles with a producer of the label’s choice. Chris Bond, who had produced Rich Girl for Hall & Oates and also had success with The Knack, was brought in and used his own preferred musicians on many of the tracks rather than Klaatu themselves.

“We resisted it,” says Davies. “He was trying to make a pop album. It didn’t work.”

The result, 1980’s Endangered Species, credited to Long, Draper and Woloschuk for the first time, was released in the US but then withdrawn. After the success of the first Klaatu album, it would have been logical for the label to suggest the band ramp up their inner Lennon and McCartney and make another Beatle-esque record. But they didn’t.

“They never asked us that,” Woloschuk says. “If anything, they wanted us to sound more American. They told us they wanted us to write songs that could be played live. They wanted us to go on a radio tour, which we did in Canada, and the album did moderately well here. In the States they buried the album.”

“There was someone in Capitol’s marketing department who didn’t like the band at all,” says Draper, “and when the album was about to ship he said: ‘If I have to promote this album, I quit!’ So Capitol didn’t market the album, and let it die so this fella would stay.”

Surprisingly, the Klaatu/Capitol relationship didn’t end there. “Rupert Perry is a very nice man, and he felt bad because he’d coerced us into coming to LA, working with a producer, hiring some strange musicians and then not promoting the record so it died a death,” says Draper. “So he allowed us to do a fifth and final album with Capitol, for Canada only and not recoupable.”

Klaatu’s final album, Magentalane, released in 1981, was made on a shoestring budget on the condition that they played live to support it. Bringing in three musicians from the newly defunct fellow Canadian band Max Webster, Klaatu went out and played shows first as support to Prism and then headlining smaller venues.

“We toured for nine months and had some fun, but couldn’t make the leap from the bars to the seated venues,” says Draper. “We filled our gigs every night because people came to see the novelty act that was once thought to be The Beatles.”

The song Knee Deep In Love from the Endangered Species album was a Top 40 hit in Canada, but the romance between Klaatu and the US was well and truly over, and the band split in 1982.

These days, the former members of Klaatu are very open about their Beatles influences. “I’m probably one of the biggest Beatles fans in the whole world,” says John Woloschuk, “but we did try to branch out into other influences, like 10cc, for example.”

“If you’re going to steal – or learn – you steal from the best,” says Terry Draper. “Nobody’s going to steal from a bad band.”

True to the philosophy that made – and then broke – them, the former members of Klaatu are still involved in music. Terry Draper and Dee Long release solo albums, Draper oversees Klaatu’s catalogue and remastering. John Woloschuk occasionally performs in a band with friends, and administers Magentalane Music to look after Klaatu’s business affairs.

“From the nineties until now, there’s been a big resurgence in interest in Klaatu,” says Frank Davies. “They held a convention in 2005 here in Toronto for Klaatu fans. People came from all over the world. The band played unplugged and the crowd loved it.”

“Our fans tend to be extremely loyal,” says Woloschuk. “They stick with us even though there hasn’t been any new Klaatu product out for decades. There are some younger fans who weren’t born when Klaatu was around.”

Steve Smith has mixed feelings about the whole Klaatu experience. “I feel kind of bad about what eventually happened when they got poo-pooed,” he says. “After it came out that they weren’t The Beatles, nobody wanted to hear it any more. I thought they were a really talented band. To this day I still like them. Hope is a fantastic album.”

“To engineer the press furore that happened was way beyond our level of intelligence,” concludes John Woloschuk. “Nobody could have planned that. We were the victims to the rumour.

“I see the gold records on my wall and I know what we accomplished. We got very good at what we were doing. It’s a shame that we weren’t allowed to have a place in the music industry workforce. We were forced out of it.”

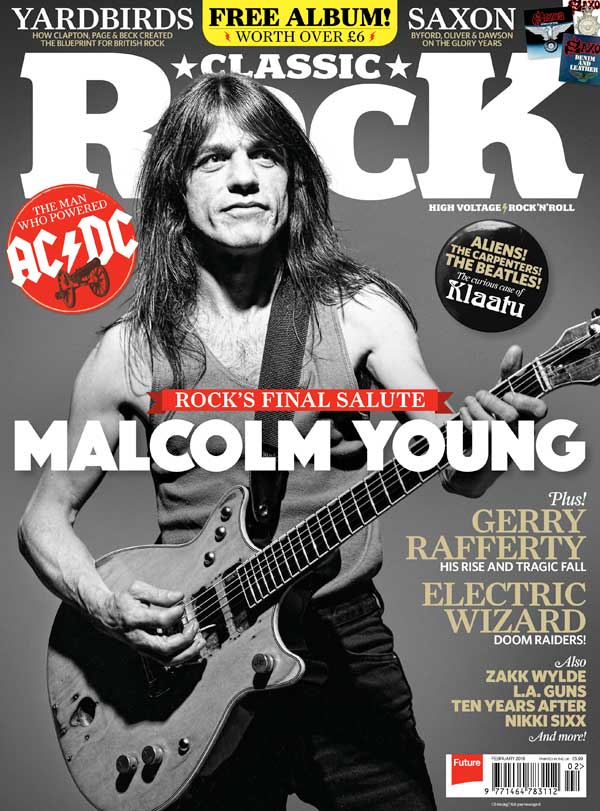

Terry Draper passed away on May 15, 2025. This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 245, published in January 2018.

Ian Ravendale began working for BBC's Radio Newcastle's Bedrock show in the 1970s and soon after started writing for local and national music magazines. He's written for Sounds, Classic Rock, AOR, Record Collector, The Word, American Songwriter, Classic Pop, Vive Le Rock, Iron Fist, The Beat, Vintage Rock and Fireworks, and worked with Tyne Tees Television and Border TV.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.