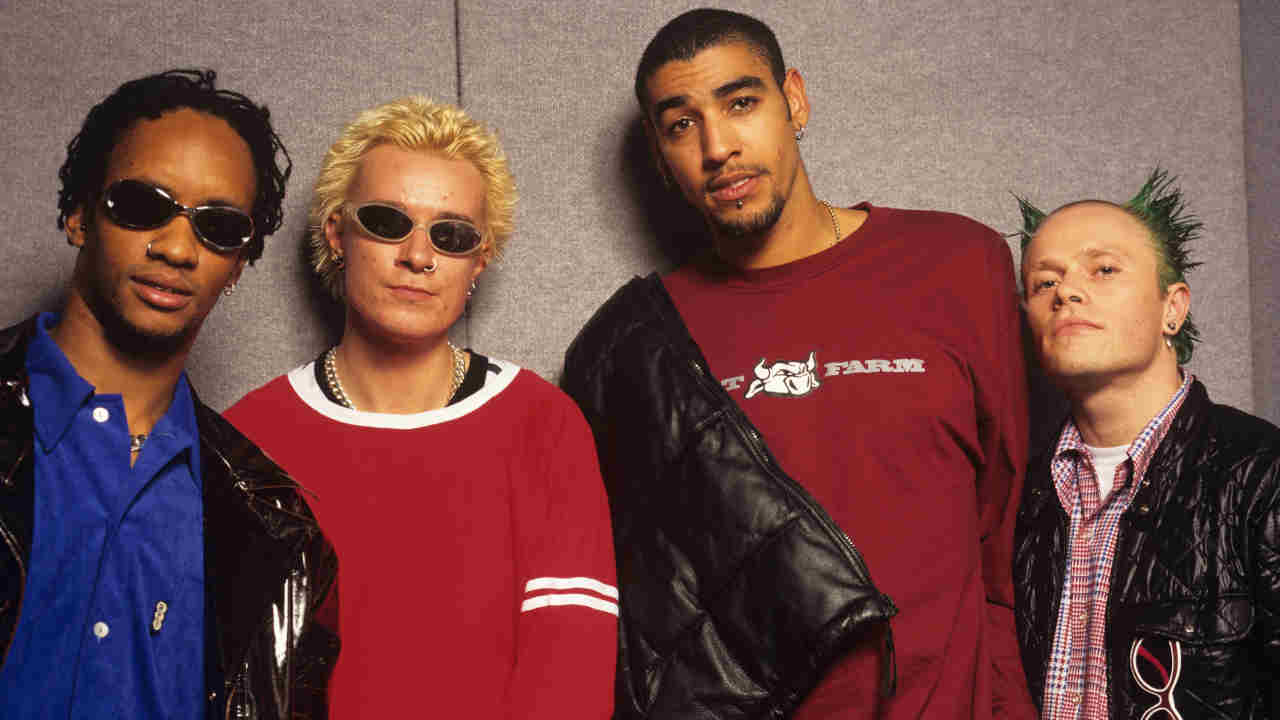

“When I look back, there’s never been any one thing that’s been normal about this band. I’m used to strangeness in my world!”: The controversial dance band who lit a fire under the 90s metal scene

How The Prodigy’s The Fat Of The Land bought aggro to dance music and rave culture to metal

When The Prodigy began appearing in metal and rock magazines in the mid-90s, not everyone was happy. Letters pages were flooded with complaints. Subscriptions were cancelled. More than one death threat was issued by a disgruntled metal fan.

In hindsight, this reaction – while OTT – was perhaps understandable. In the early 90s, the band and the rave scene they emerged from was seen as the enemy. The antithesis of heavy music, it was the preserve of white-gloved button-pushers who would happily dance around a car alarm. The bottom line was simple: rock and dance did not mix.

All that began to change in 1994 with the release of The Prodigy’s second album, Music For The Jilted Generation, which included a couple of rock-orientated tunes – Their Law and Voodoo People.

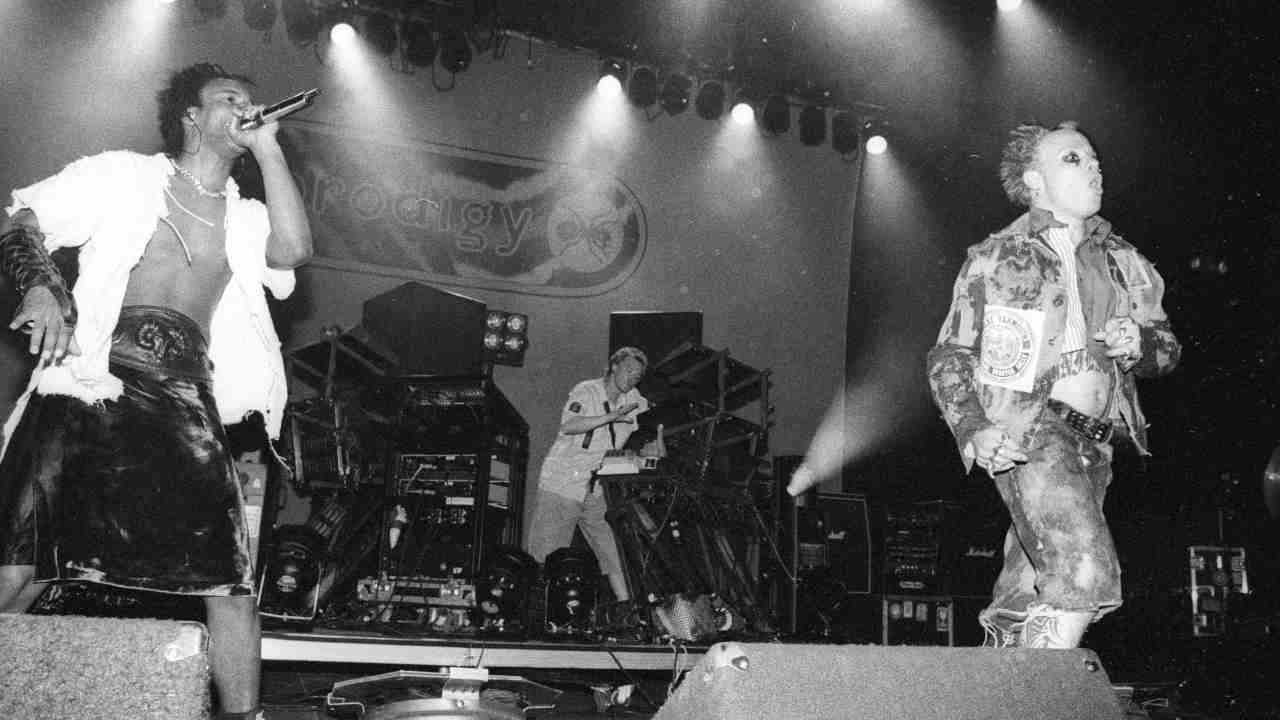

But it wasn’t until a truly incendiary Glastonbury performance in ’95 that it became obvious that The Prodigy were morphing into something very special and utterly unique; a mad hybrid of rock and punk, hip hop and dance music, that had the ability to bring all these disparate tribes together. Even then, most fans discovered them more by luck than judgement.

And then, in March 1996, The Prodigy released their new single. Its incendiary title told you all you needed to know: Firestarter. Helped along by a video featuring late vocalist/ringmaster of chaos Keith Flint bugging out in an underground tunnel, the single went straight to Number One, prompting questions in Parliament about the two-mohawked lunatic advocating arson. The Prodigy were too big to ignore – and rock fans started to get it.

“That’s what you want, innit!” grins Prodigy founder/leader/genius Liam Howlett, remembering the controversy. “But at the same time I thought, was there nothing else more important going on that they had to talk about my record? Get on with running the country, you cunts!”

Despite the success of Firestarter, and its equally provocative follow-up singles Breathe and Smack My Bitch Up, there was still resistance from the more diehard quarters of the metal community. Some remained vehemently opposed to these upstarts imposing dance beats on ‘their’ music. For Liam himself, it was never quite as simple as The Prodigy becoming a rock band.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I was into hip hop before The Prodigy started,” he says, “and at that time it was quite noisy in its sound. If you listen to Public Enemy, it was loud, chaotic, a real ‘fuck you’ sound. Then when the east London breakbeat sound started happening, I heard that chaos and noise in those records, so I got drawn in.”

it was never like we were moving into rock music. We just brought back the edge I wanted.

Liam Howlett

Growing bored with hip hop, Liam started going to raves, but that, too, became stale, eventually feeling safe and repetitive. The Prodigy were in LA when Rage Against The Machine’s debut was released, and had also been playing festivals alongside the likes of Suicidal Tendencies and Biohazard. Tired of playing to undiscerning ravers, The Prodigy wanted the rock crowd.

“But it was never like we were moving into rock music,” argues Liam. “We just expanded our sound and brought back the edge I wanted. I will say, though, that the fundamental underpinning sound of the beats and bass never changed; that attack has always stayed the same from our first record to now.”

By 1997, The Prodigy had proved their mettle – and indeed their metal – on the festival circuit, blowing away the opposition at the likes of Reading, Phoenix Festival, and T In The Park, something Liam says was very important in winning over a new audience. “We bent people towards what we were doing, rather than trying to fit into the rock scene,” he says.

If Firestarter had laid the groundwork, then The Prodigy’s third album, The Fat Of The Land, sealed it for them. Released in June 1997, anticipation had reached fever pitch – the world was gagging for it.

Matters were helped along by another burst of controversy, this time surrounding the single Smack My Bitch Up and its no-holds-barred drug-taking’n’nudity video. After complaints from feminist groups about the track, the album was pulled from the shelves of certain record stores, but that didn’t stop it going to Number One in more than 20 countries including the US and UK.

“It’s alright,” says Liam, modestly reflecting on the album. “I mean, there’s five killer tunes on there. Smack My Bitch Up is still our live anthem, and the sound still hits hard and fresh today, so I got that mix right, which I’m proud of. I don’t think it’s our best album, as a whole, but it has two or three of our best tunes, and it signifies a good moment in time when barriers had been broken down.”

Smack My Bitch Up is still our live anthem, and the sound still hits hard and fresh.

Liam Howlett

He’s understating the impact of the record and its enormous influence on the rock scene. Everyone from Biohazard and Sepultura to Gene Simmons (no, really) have covered songs from Fat Of The Land, and the big beats that were then so unusual in rock are now almost commonplace. The Prodigy became Download fixtures, finally headlining the main stage in 2012, even if they still weren’t totally accepted by sections of the metal crowd. For anyone else, that would have been frustrating. Not for Liam Howlett.

“Nah, man, never,” he laughs. “We loved it. We weren’t trying get accepted, we didn’t give a fuck. We were simply telling people, with our tunes, there’s another heavy attacking sound here and a new angle. I think once people had seen us live, it was easier to understand.”

“Nah, man, never,” he laughs. “We loved it. We weren’t trying get accepted, we didn’t give a fuck. We were simply telling people, with our tunes, there’s another heavy attacking sound here and a new angle. I think once people had seen us live, it was easier to understand.”

More than 25 years after the release of their best-known album, The Prodigy haven’t eased up on their confrontational approach. “None of my influences have changed,” says Liam. “I think your influences when you first start writing music always stay with you and never leave.

From the attack and groove of the Rage sound, to the chaos and beats of Public Enemy and [their production team] The Bomb Squad… Then I’ve just plugged into tunes and bands that have affected me along the way. System Of

A Down always inspire me, and they’re a band who do shit their own way. They don’t sound like anybody else… and we don’t wanna sound like anybody else!”

Ask him now to sum up the impact and influence of The Fat Of The Land and Liam simply shrugs. “Fuck knows, and I don’t wanna know.” That type of thing, he says, is for other people to analyse and write about. “We’re just doing our thing and pushing forward.”

He will, however, confess that it’s a little strange for

The Fat Of The Land to be considered a classic ‘metal’ album, given the band’s sometimes rocky history with the genre.

“Yeah, it does feel strange,” he ponders. “But when I look back, there’s never been any one thing that’s been normal about this band. I’m used to strangeness in my world!”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 299 (July 2017)

A veteran of rock, punk and metal journalism for almost three decades, across his career Mörat has interviewed countless music legends for the likes of Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Kerrang! and more. He's also an accomplished photographer and author whose first novel, The Road To Ferocity, was published in 2014. Famously, it was none other than Motörhead icon and dear friend Lemmy who christened Mörat with his moniker.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.