Why you should definitely own Workingman's Dead by the Grateful Dead

Country rock with a heart and soul, Workingman's Dead reminded people that Jerry Garcia & Co. were more than just live-jamming road hog

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The Grateful Dead had laboured long and hard to create a stage performance that was emblematic of their questing spirit where improvisation and a loose, lean country-blues style suited an audience comprised mostly of stoned freaks. But then The Band’s second album came out of nowhere and changed the musical landscape of the early 70s.

No group acknowledged The Band’s impact more than the Grateful Dead, for working in the studio had always proved irksome to the latter. Even the arrival of lyricist Robert Hunter for the Dead’s third album Aoxomoxoa had failed to mesh the gears, and they had ended up in debt to Warner Bros to the tune of $180,000 (which was only redressed by the live album Live Dead).

Hunter and the Dead’s principal vocalist and guitarist, Jerry Garcia, had known one another for years: “We both got out of the army around the same time,” Hunter recalled. “We formed a folk duet for a while, then several old-timey and bluegrass bands which eventually led to the Grateful Dead.”

This was the starting point for what was to become Workingman’s Dead: “We just had our fill of writing psychedelia and reverted to form,” Hunter said.

Reverting to form, though, was something of an oversimplification. The group had endured several setbacks in the weeks preceding the sessions in early 1970, one of which was being busted for possession in New Orleans. (The bust was immortalised on the song Truckin’, which appeared on the next album, American Beauty.) Then, while the sessions were taking place it was discovered that the band’s manager, Lenny Hart, had siphoned off thousands of dollars and done a runner.

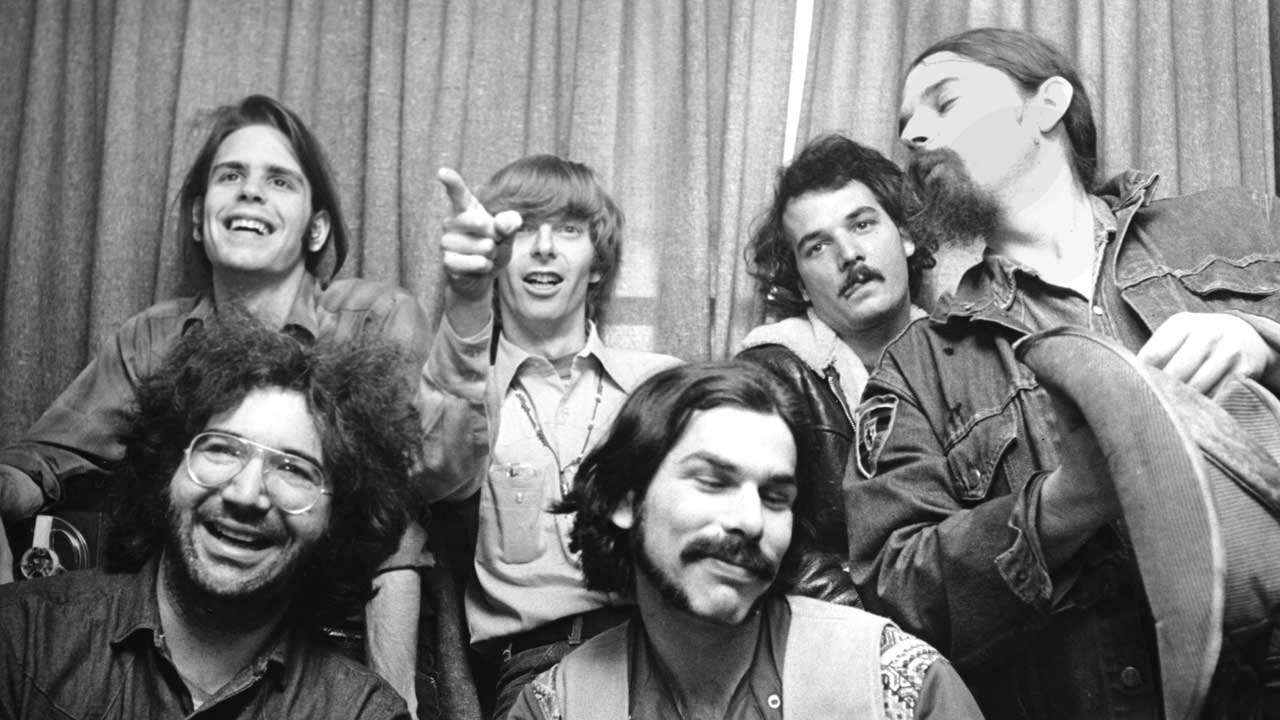

Despite these setback, though, Workingman’s Dead was a cohesive and organic album, on which the sequencing of tracks played as big a part in the overall conception as the songs themselves. But there was nothing contrived about it. It exuded an atmosphere of laid-back zonkedness. The sepia sleeve featured a monochrome photograph of the band hanging on a street corner in San Francisco’s Mission District, but perhaps the most telling detail is a tired and emotional Bill Kreutzmann slumped on some steps in a doorway

Superficially, the songs evoked images of a bygone era, where drifters and grifters, hucksters and shucksters, and ladies of easy virtue all rubbed shoulders with a cosy familiarity. Yet the detail of the lyrics was pure rock’n’roll, irrespective of specific era. ‘High Time’ captured the spirit of Hank Williams and would have sounded right on jukeboxes in the late 40s.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Casey Jones may conjure up images of hobos riding the trains in the depression, but "Riding that train/High on cocaine" was more consistent with the rock’n’roll era than with that of the dispossessed in the 30s. Uncle John’s Band seemed more an affectionate, airbrushed take on the Dead’s early years. It was as the cover suggested a snapshot of the group, stripped of the appurtenances of psychedelia and dumped right back into the setting from which they had sprung.

Surprisingly, Workingman’s Dead established the Dead as a group capable of recording imposing studio albums. It duly cracked the US Top 30, while Uncle John’s Band and Casey Jones picked up enough airplay to become radio hits. The Dead’s future was assured.

Hugh Gregory is the author of A Century Of Pop, which describes the history of popular music of the 20th century, from Victorian hymns and West African drum rythms, through light opera and Vaudeville, to the techno-driven music of the 1990s.