The Stereophonics: are they rock's least respected band?

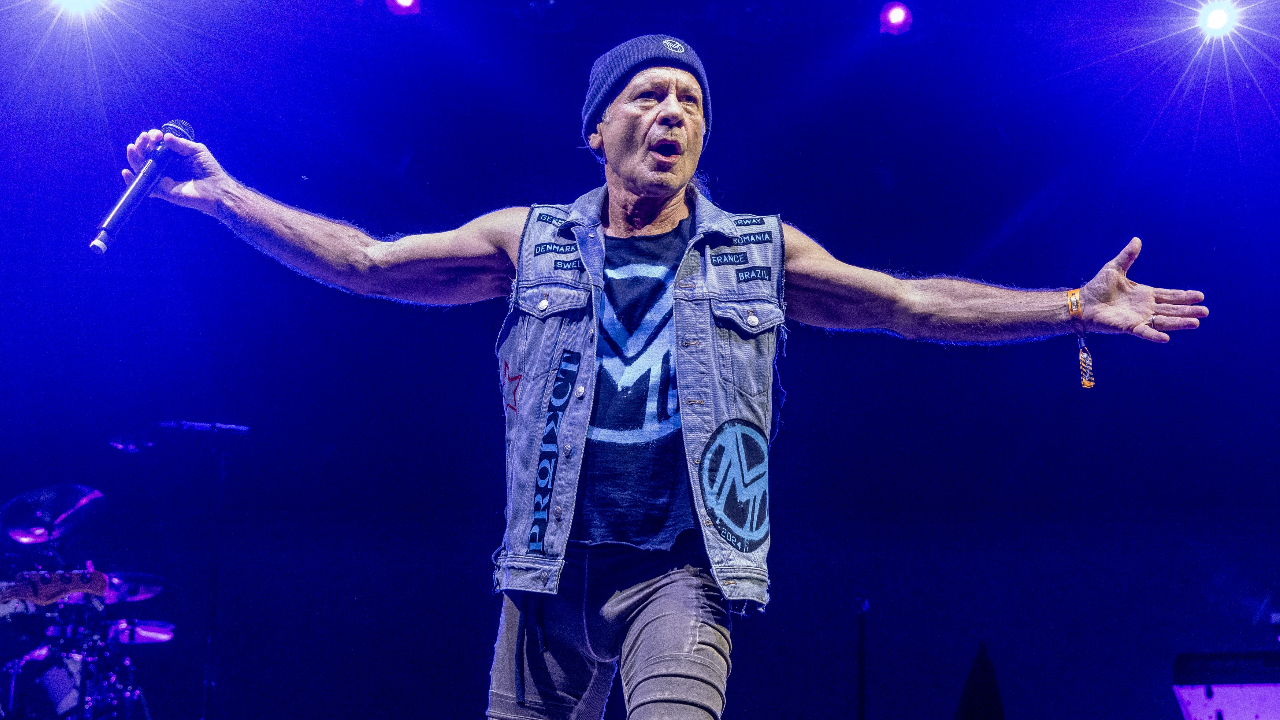

Despite a chart-topping, arena-filling career, Stereophonics are often viewed with disdain by the hard rock audience. But Kelly Jones is still a rock kid at heart…

Kelly Jones takes a sip of English breakfast tea, and talks about drinking. He’s dressed in an impeccably cut navy blue sports coat – “I bought it in Japan,” he reveals, “because they make really good clothes for the, er, smaller man out there” – and boasts an impeccably tousled head of lustrous black hair that he admits he “dyes a little”. The 41-year-old Welshman tells us that his plans for the coming weekend, now just hours away, include a visit to the Old Country, his home town of Cwmaman. There, on Sunday, he will spend the afternoon in the company of lifelong friends, bending the elbow in the unreconstructed splendour of his one-time local, The Globe. After a week of interviews in support of Stereophonics’ forthcoming album, Keep The Village Alive, this prospect awaits like a hot bath at the end of a cold and troublesome day.

“I love to go back there,” he says. “It’s not that it keeps me grounded because I think I’m a pretty grounded person anyway, but it’s good to be in the company of people who have known me for so many years, people who don’t define me by what I do for a living. They’re supportive – like if we’re playing in Glasgow, say, they’ll hire a minibus and come up to the show – but in social situations I’m not Kelly from the Stereophonics, I’m just Kelly.”

That Kelly Jones can melt back into a community he left almost a generation ago for the blinding lights of West London (a manor on which he still lives, with his partner and two daughters) is telling. It’s tempting to gild the lily when it comes to picturing the contrasts between the reality of Kelly Jones’ environment and that of the place he still refers to as “home”. His life, presumably, is markedly different from that of his friends who still wake each day in the Welsh valleys, not least in terms of disposable income. But the notion that this disparity has led to a reduction of common ground is here given vanishingly short shrift. “That stuff doesn’t really matter to them, or to me,” he says. “It’s not important.”

What do you mean by ‘stuff’?

“Our success, I suppose,” he answers, with a measure of self‑consciousness. “When I’m in The Globe with my old mates, it’s just not important. In there, if I’m being a wanker, they’ll tell me I’m being a wanker. It feels very natural. It feels very normal.”

Normality may be a quality that harmonises with the root notes of Kelly Jones’s personality, but today at least it appears to be in limited supply. It’s Friday lunchtime in Central London. Outside on the Portobello Road the rain hammers out a drum solo on the skins of a thousand umbrellas. Sitting at a table at Electric House – a private members’ bar – Jones sips his sugarless tea in a large, bustling room aglow with tasteful wealth. Just seconds after he has spoken of his friends at The Globe – friends who would not be welcome here – the songwriter is interrupted by a visitor to the table. Looking up, Jones’s expression registers pleasurable surprise as he recognises the face of actor Dougray Scott. Standing now, the two men embrace. The Welshman tells the Scot that he’ll come and find him for a proper catch-up as soon as he’s finished.

Who was that? Was it…

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Dougray Scott.”

Get you and your famous friends!

Jones smiles. Sort of. “He’s a good guy,” he says.

When Stereophonics first found fame at the end of the last century, Jones was certain it wouldn’t last. As songs such as Local Boy In The Photograph found favour with an audience in the market for something a little more muscular than the sounds offered by Britpop, the then young Welshman viewed his group’s good fortune with acute suspicion. Even when the heights went from dizzying to vertiginous (such as the group’s headline show at Donington Park in support of 2001’s Just Enough Education To Perform album), the now increasingly famous frontman remained convinced of the impermanence of it all.

“We got to the point where we were playing arenas and I remember looking out at thousands and thousands of people and I’d be thinking, ‘Well, this can’t last,’” he says. “I don’t think I actually realised it then, but I just didn’t know how to enjoy the moment. I just thought it was all going to disappear, or go wrong somehow. I wasn’t relaxed at all – I was uptight and I was guarded.”

And now?

Jones smiles, this time with an easy warmth.

“Let’s just say that these days I’m much more comfortable with it all.”

When Stereophonics first banded together – as a triumvirate completed by bassist Richard Jones and then drummer Stuart Cable – their ideals could not have been less fashionable: they wanted to be a pub rock band, playing pub rock music, in pubs. This point was emphasised to this reporter by Stuart Cable himself, in a tone of genuine glee, backstage at a Radio 1 concert in Manchester in May 2003 (his resonant Welsh accent made it sound as if he were saying ‘punk rock’, which even with that genre’s elastic boundaries would be pushing it a bit).

The pub aspect of the term is fitting, as Stereophonics were friends long before they were bandmates. So embedded were the group’s roots that Stuart Cable actually used to babysit Kelly Jones. Four years the frontman’s senior, the drummer would show his young charge episodes of The Young Ones. The pair would listen to hard rock and metal, with Jones recalling “that those were the days of denim jackets that were covered in patches, and we were really into that.”

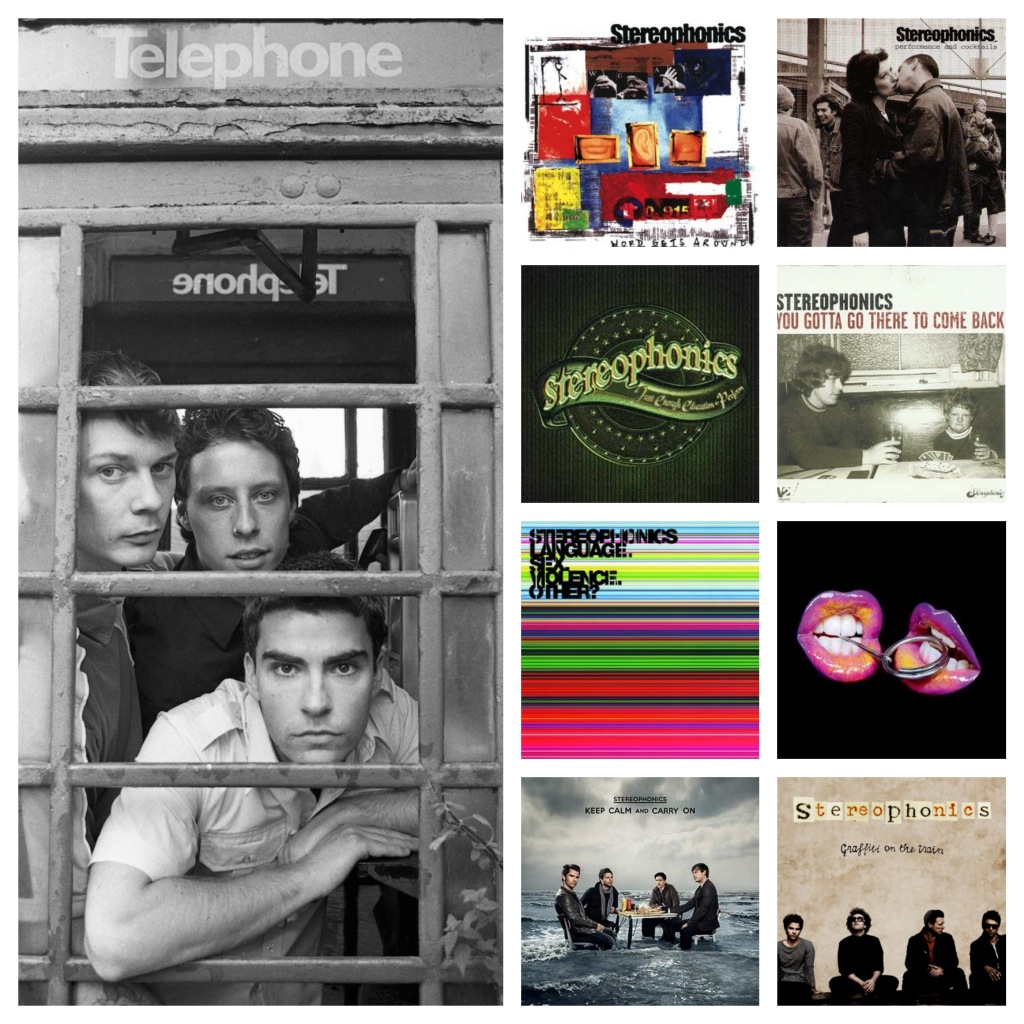

Like all before him, Jones paid his dues, along with Stuart Cable and bassist Richard Jones, in nearby streets and towns, playing the not always forgiving working men’s clubs. Back in this day, the group were called Tragic Love Company, a tribute to their key influences – Mother Love Bone, Bad Company and Canadian rock megastars The Tragically Hip. Swapping their crap name for a decent one, in 1996 Stereophonics became the first band signed to the V2 label, the newest major on the block at the time. A year later, their debut album, Word Gets Around, amplified the summer of Britpop by walloping its way into the Top 10. Aged 23, it had at that point already been 11 years since Kelly Jones first played onstage in time to a drumbeat laid down by Stuart Cable.

“When I think of Stuart, I think of his smile,” says the frontman today.

Stuart Cable died in 2010 as a result of choking on his own vomit after a heavy drinking session. So far, so tragically clichéd. At the time of his passing, the drummer was no longer a member of the band, but if you think that this detail is pertinent in any meaningful way, you would be wrong.

“Stuart had a blip for a period that lasted about six months,” recalls Jones. “He started missing shows and so something had to change. But just because Stuart wasn’t in the band any more, that doesn’t mean we weren’t friends. We stayed friends. We even played together one time – we were drunk at a friend’s wedding and we got onstage. I talked to him on the phone the night before he died. And if he hadn’t died it wouldn’t have surprised me at all if he rejoined the band.”

You miss him.

“Of course I miss him.”

But if the death of Stuart Cable supplied Jones with his first taste of genuine public tragedy, elsewhere the business of being in a band was in some senses more grindingly routine. It’s common for members of the music press to obsess about how artists are perceived by the ‘critical community’ and by ‘opinion formers.’ But even so, the level of dismissiveness and disdain that has over the years attached itself to the Stereophonics from people who receive their albums for free is startling. In some quarters it’s as if the band are poison – like Nickelback, say, or Puddle Of Mudd. One doesn’t have to think very much at all of Jones’s music to believe that neither he nor his group receive the respect they deserve.

“That’s not for me to judge,” is his answer when pressed on the matter.

Okay then, let’s try this. Stereophonics find themselves in the invidious position of being seen as ‘uncool’ by the musical tastemakers of London – and unsuitable, even, for enjoyment in an ‘ironic’ sense . Despite the fact that when the mood takes them they can rock very hard indeed, nonetheless it’s tempting to view Stereophonics as being the kind of act savoured by people who buy their music at the supermarket.

At least from the band’s point of view, this is harsh (if not frustrating, at least not these days). The past ubiquity of songs such as Have A Nice Day – itself a far more thorny and complicated lyric than suggested by its title – have rendered the band as aural wallpaper: everywhere, yet largely unnoticed. In fact, so ostracised were the band from the field of music they grew up listening to, and so unlikely was it that they would be ever invited to perform at the Download festival, that on July 14, 2001, Stereophonics booked Donington Park for their own headline show, to which 60,000 people paid entry. They are the only group to appear at the East Midlands racetrack under their own wing, and not as part of the Monsters Of Rock or Download festivals.

“When I was growing up, the Monsters Of Rock festival was a big deal to me,” Jones recalls. “I’d read about it in all the magazines and think it just looked amazing. The bands all looked really cool and there seemed to be so much passion there. I felt I could relate to that. I also remember seeing people’s Monsters Of Rock patches on their denim jackets, with the monster climbing over the name of the headliner. I just thought that was so cool.”

And there’s that word again – cool. A year before Stereophonics graced the spiritual home of British rock, on September 22 Jones appeared onstage at the Royal Albert Hall with The Who, where he sang the lead vocal for Substitute. Other artists who joined the redoubtable rock legends onstage that night included Noel Gallagher, Eddie Vedder and Paul Weller. It’s gently put to the Welshman that while these three performers are largely lionised by the press, are seen as being cool, he, well, isn’t.

He allows himself a brief smile of recognition. Then he says: “I’m friends with Paul Weller, actually. There’s been times when we’ve been walking down the street and he’ll say to me, ‘You know, I was reading something about you the other day and it really pissed me off!’ He’ll say things like, ‘They really got it wrong,’ and feel aggrieved on my behalf. It’s quite sweet, really.”

Paul Weller’s agitation is not, however, shared by Jones. In a decision of supreme rarity, the singer hasn’t read a single word that has been written about himself or his band for almost 15 years. Jones believes that reading the opinions of strangers serves only to corrupt his creativity. But it’s likely that it also has something to do with the tone of quiet negativity that attaches itself to so many of this band’s notices from the press.

“When we started out, the written media was the one aspect of what we did that I struggled with,” he says. “We were a band, it was three of us, but the focus seemed to be just on me, and I wasn’t comfortable with that. But me not reading our press is also just about the fact that [what’s written] isn’t relevant to me. And I don’t only mean the negative things that are written, either. I know what I think of our music, and I know what I think of the albums we’ve made, so the opinions of people in the press don’t matter to me. I don’t mean that in an arrogant way, either.”

But it wasn’t always thus. Because the music press offers no right of reply, in 2003 the Stereophonics famously carved their own. The lead-off single from Just Enough Education To Perform was Mr Writer, an excoriating riposte to a journalist who flew to LA to interview the group – at their expense – and who after seemingly enjoying the musicians’ company returned to write a grandly negative article. Clearly, the experience chafed a bit.

“I can’t believe that all these years later I’m still being asked about that song,” remarks Jones, not unkindly, despite the fact that his interviewer hasn’t asked about the song. “That song is about one specific journalist. But the press seemed to think that it was about them as a whole. I’d sit down for interviews and the first question would be, ‘So, why do you hate music journalists?’ They would have made up their mind that I hated them even before the interview had started. So was I guarded? Yes, of course. How could I not be guarded?”

Twelve years after the fact, would you care to name the journalist who inspired Mr Writer?

“No.”

Okay then. Have you been in the journalist’s company since you wrote the song?

“No.”

It seems only fair to mount a case for the defence for Kelly Jones and the Stereophonics. There is, of course, craft and skill in the band’s music, an innate and careful understanding of the mechanics and heritage of rock music that comes married to arrangements that are expert and often masterful. And while some bands’ adherence to tradition means that were they to be any more meat’n’potatoes they would turn into a shepherd’s pie, the Stereophonics’ comfort food usually comes with a modern and inventive spin.

There’s artistry here too. While lyrically Mr Writer is the band’s most artless track, elsewhere the end result of tiny acorns of creativity are quite something to behold. The song Graffiti On The Train sprang to life after Jones was awoken by the sound of people on his roof, whom he presumed were set to burgle his home. When challenged, it turned out that the lads were on their way to the train tracks in order to spray paint trains. This incident first became a song, and has since grown into a screenplay written by Jones and which he hopes will become a feature film that, naturally, he intends to direct (the project has temporarily stalled due to funding problems).

Elsewhere, Keep The Village Alive’s finest song, Mr And Mrs Smith, tells the tale of an illicit affair between two lovers who ‘meet every Friday night under false names’, one of whom has ‘got style, she’s got grace, she’s got every little thing but a smile on her face’. Always deft, occasionally thunderous – opening track C’est La Vie hears Jones sound a lot more like John Lydon than Rod Stewart – at its best, Keep The Village Alive attains a status that shares a title with this very magazine.

“I’m really proud of this album,” is how its author speaks of a collection that was a pleasure to record but a nightmare to mix. “I’m really proud of each of the songs, obviously, but I’m also really proud of the variety of the songs on there. I think we cover a lot of ground and do it really well. I don’t think there are many bands that do that.”

And at that our time is up. Next is an interviewer from The Sun, asking another set of questions for an article the songwriter will decline to read. But despite this snub, Jones is an engaging interviewee, a man who seems perfectly at ease man-hugging movie stars while contemplating an afternoon with the old gang in a home‑town pub. And while an hour in a person’s company is sufficient only to measure what someone is like to be interviewed rather than what they’re like for the rest of the time, today Jones is different from the person I first questioned more than a decade ago. He isn’t guarded, he isn’t suspicious and he isn’t in the least bit concerned about things that stand outside of his control.

In this sense, he has become the thing that suits him best: he’s grown into the role of the Everyday Rock Star.

Barnsley-born author and writer Ian Winwood contributes to The Telegraph, The Times, Alternative Press and Times Radio, and has written for Kerrang!, NME, Mojo, Q and Revolver, among others. His favourite albums are Elvis Costello's King Of America and Motorhead's No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith. His favourite books are Thomas Pynchon's Vineland and Paul Auster's Mr Vertigo. His own latest book, Bodies: Life and Death in Music, is out now on Faber & Faber and is described as "genuinely eye-popping" by The Guardian, "electrifying" by Kerrang! and "an essential read" by Classic Rock. He lives in Camden Town.